Pronunciation of English ⟨wh⟩: Difference between revisions

markup repair |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The pronunciation of the [[Wh (digraph)|digraph ⟨wh⟩]] in [[English language|English]] has varied with time, and can still vary today between different regions. According to the [[Phonological history of English consonants|historical period]] and the [[Regional accents of English|accent of the speaker]], it is most commonly realised as the [[consonant cluster]] {{IPA|/hw/}} or as {{IPA|/w/}}. Before [[roundedness|rounded vowels]], as in ''who'' and ''whole,'' it is often realized as {{IPA|/h/}}. |

The pronunciation of the [[Wh (digraph)|digraph ⟨wh⟩]] in [[English language|English]] has varied with time, and can still vary today between different regions. According to the [[Phonological history of English consonants|historical period]] and the [[Regional accents of English|accent of the speaker]], it is most commonly realised as the [[consonant cluster]] {{IPA|/hw/}} or as {{IPA|/w/}}. Before [[roundedness|rounded vowels]], as in ''who'' and ''whole,'' it is often realized as {{IPA|/h/}}. |

||

The historical pronunciation of this digraph |

The historical pronunciation of this digraph was in most cases {{IPA|/hw/}}, but in most dialects of English it has now merged with {{IPA|/w/}}, a process known as the "'''wine–whine merger'''". In dialects which maintain the distinction, it is generally transcribed {{IPAblink|ʍ}}, and is equivalent to a voiceless {{IPA|[w̥]}} or {{IPA|[hw̥]}}. |

||

==Early history of ⟨wh⟩== |

==Early history of ⟨wh⟩== |

||

Revision as of 00:03, 30 May 2012

The pronunciation of the digraph ⟨wh⟩ in English has varied with time, and can still vary today between different regions. According to the historical period and the accent of the speaker, it is most commonly realised as the consonant cluster /hw/ or as /w/. Before rounded vowels, as in who and whole, it is often realized as /h/.

The historical pronunciation of this digraph was in most cases /hw/, but in most dialects of English it has now merged with /w/, a process known as the "wine–whine merger". In dialects which maintain the distinction, it is generally transcribed [ʍ], and is equivalent to a voiceless [w̥] or [hw̥].

Early history of ⟨wh⟩

What is now English ⟨wh⟩ originated as the Proto-Indo-European consonant *kʷ. As a result of Grimm's Law, Indo-European voiceless stops became voiceless fricatives in most environments in Germanic languages. Thus the labialized velar stop *kʷ initially became presumably a labialized velar fricative *xʷ in pre-Proto-Germanic, then probably becoming *[ʍ] in Proto-Germanic proper. The sound was used in Gothic and represented by the symbol known as hwair; in Old English it was spelled as ⟨hw⟩. The spelling was changed to ⟨wh⟩ in Middle English, but it retained the pronunciation [ʍ], in some dialects as late as the present day.

Because Proto-Indo-European interrogative words typically began with *kʷ, English interrogative words (such as who, which, what, when, where) typically begin with ⟨wh⟩. As a result of this tendency, a common grammatical phenomenon affecting interrogative words has been given the name wh-movement, even in reference to languages in which interrogative words do not begin with ⟨wh⟩.

Labialization of /h/ and delabialization of /hw/

In the 15th century, historic /h/ was labialized before a rounded vowel, such as /uː/ or /oː/, and came to be written ⟨hw⟩. The labialization did not occur in all dialects. Later in many dialects /hw/ was delabialized to /h/ in this same environment, whether or not it was the historic pronunciation; in others, the /h/ was dropped, leaving /w/.

- who - /huː/ (Old English hwā)

- whom - /huːm/ (Old English hwǣm)

- whole - /hoʊl/ (Old English hāl—cf. 'hale')

In Kent, the word 'home' is pronounced /woʊm/; the /h/ was labialized to /hw/ before the /oʊ/, and later Kentish became an h-dropping dialect.

Wh-labiodentalization

Wh-labiodentalization is the merger of /hw/ and the voiceless labiodental fricative /f/. It has occurred in some dialects of Scots, and in Hiberno-English with an Irish Gaelic substrate influence (something which has led to an interesting re-borrowing of whisk(e)y as [fuisce] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), having originally entered English from Scottish Gaelic). In Scots this leads to pronunciations like:

- whit ("what") - /fɪt/

- whan ("when") - /fan/

Whine and fine are homophonous /fain/.[1]

Wine–whine merger

The wine–whine merger is a merger by which voiceless /hw/ is reduced to voiced /w/. It has occurred historically in the dialects of the great majority of English speakers. The resulting /w/ is generally pronounced [w], but sometimes [hw̥]; this may be hypercorrection.

The merger is essentially complete in England, Wales, the West Indies, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, and is widespread in the United States and Canada. In accents with the merger, pairs like wine/whine, wet/whet, weather/whether, wail/whale, Wales/whales, wear/where, witch/which etc. are homophonous. The merger is not found in Scotland, Ireland (except in the popular speech of Dublin, although the merger is now spreading more widely), and parts of the U.S. and Canada. The merger (or the lack thereof) is not usually stigmatized except occasionally by very speech-conscious people, although the American television show King of the Hill pokes fun at the issue through character Hank Hill's use of the hypercorrected [hw̥] version in his speech. A similar gag can be found in several episodes of Family Guy, with Brian becoming extremely annoyed by Stewie's over-emphasis of the /hw/ sound in his pronunciation of "Cool hWhip" and "hWil hWheaton".[4]

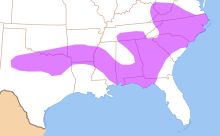

According to Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 49),[3] while there are regions of the U.S. (particularly in the Southeast) where speakers keeping the distinction are about as numerous as those having the merger, there are no regions where the preservation of the distinction is predominant (see map). Throughout the U.S. and Canada, about 83% of respondents in the survey had the merger completely, while about 17% preserved at least some trace of the distinction.

The wine–whine merger, although apparently present in the south of England as early as the 13th century,[5] did not become acceptable in educated speech until the late 18th century. While some RP speakers still use /hw/, most accents of England, Wales, West Indies and the southern hemisphere have only /w/.

| Homophonous pairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phonology

Phonologically, the sound of the ⟨wh⟩ in words like whine in accents without the merger is either analyzed as the consonant cluster /hw/, and it is transcribed so in most dictionaries, or as a single phoneme /ʍ/, since it is sometimes realized as the single sound [ʍ]. The primary argument for it being a single phoneme is that /h/ does not form any other consonant clusters apart from /hj/ in words like 'hue' /hjuː/, and that can be analyzed as /h/ plus the diphthong /juː/ rather than as a cluster. Arguments for it being a consonant cluster are that the single-cluster argument is not convincing: only /s/ and /r/ form many clusters, and /ʃ/, for example, is only found as /ʃr/ apart from Yiddish borrowings; that historically there were several other h-clusters (/hn, hr, hl/), of which /hw/ is the last remaining; that speakers' intuition is that it is two consonants; and that in some dialects, such as in parts of Texas, the /h/ is being lost from /hj/ (as in "Houston")[citation needed] just as it was lost earlier from /hw/ and despite the fact that these are not h-dropping dialects, suggesting cluster simplification.

See also

References

- ^ This phenomenon has also occurred in most varieties of Maori.

- ^ Based on www.ling.upenn.edu and the map at Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 50).

- ^ a b Labov, William (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cool Whip". Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Minkova, Donka (2004). "Philology, linguistics, and the history of /hw/~/w/". In In Anne Curzan and Kimberly Emmons, eds., (ed.). Studies in the History of the English language II: Unfolding Conversations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 7–46. ISBN 3-11-018097-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)