Rodney King: Difference between revisions

Ranger2000 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

{{weasel|date=October 2012}} |

{{weasel|date=October 2012}} |

||

Sergeant Stacey Koon |

At that point LAPD Sergeant Stacey Koon, the ranking office on scene, told Singer that LAPD was taking tactical command of the situation. He ordered all officers to holster their weapons.{{citation needed|date=October 2012}} LAPD officers are taught not to approach a suspect with a drawn gun, as there is a risk that a suspect may gain control of it if an officer gets too close.<ref>Cannon. ''Official Negligence'': p. 28.</ref> Koon then ordered the four other LAPD officers at the scene, Briseno, Powell, Solano, and Wind, to subdue and handcuff King using a technique called a "swarm." This involves multiple officers grabbing a suspect with empty hands, in order to quickly overcome potential resistance. As the officers attempted to restrain King, King resisted, standing to remove Officers Powell and Briseno from his back. Koon ordered the officers to fall back.{{citation needed|date=October 2012}} The officers later testified that they believed King was under the influence of the dissociative drug [[phencyclidine]] (PCP),<ref>Cannon. ''Official Negligence'': {{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> although King's toxicology tested negative for the drug.<ref>Cannon, Lou (March 16, 1993). "[http://tech.mit.edu/V113/N14/king.14w.html Prosecution Rests Case in Rodney King Beating]". ''[[The Washington Post]]''. Retrieved 2009-12-01.</ref> |

||

===Beating with batons: events on the Holliday video=== |

===Beating with batons: events on the Holliday video=== |

||

Revision as of 19:26, 17 December 2012

Rodney King | |

|---|---|

King in April 2012 | |

| Born | Rodney Glen King April 2, 1965 Sacramento, California, U.S. |

| Died | June 17, 2012 (aged 47)[1] Rialto, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | accidental drowning |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Victim of civil rights violation involving police brutality |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m)[2] |

| Criminal charge | Robbery |

| Criminal penalty | 2 years imprisonment |

| Spouse(s) | Crystal Waters (divorced) Danetta Lyles (divorced) |

| Partner | Cynthia Kelly (fiancée)[3] |

| Children | 3 daughters |

Rodney Glen King (April 2, 1965 – June 17, 2012) was an African-American construction worker that while on parole for robbery became nationally known after being beaten with excessive force by Los Angeles police officers following a high-speed car chase on March 3, 1991. George Holliday, a resident in the nearby area, witnessed the beating and videotaped much of it from the balcony of his nearby apartment.

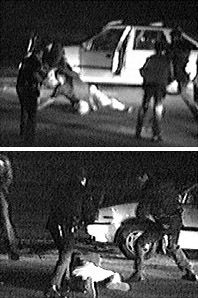

The videotaped footage shows five Los Angeles area officers surrounding King, with several of them striking him repeatedly. During the struggle to subdue King, other officers stood by, without seeming to take action to stop King from being struck. A portion of the footage was aired around the world, inflaming public outrage in Los Angeles and other American cities where racial tension was often high. The videotape also increased public sensitivity to, and anger about police brutality, racism, and other social inequalities throughout the United States.

Four of the police officers from the LAPD who took part in the incident were charged in Los Angeles County Superior Court with assault with a deadly weapon and use of excessive force for their conduct during the incident. After a judicial finding that a fair and impartial jury could not be impaneled in Los Angeles County the case was given a change of venue to Simi Valley, in Ventura County where they were tried. On April 29, 1992 three of the four police officers, (Koon, Wind, and Briseno) were acquitted of all charges. The jury acquitted the fourth officer, (Powell), on the assault with a deadly weapon charge but failed to reach a verdict on the use of excessive force charge. The jury deadlocked at 8-4 in favor of acquittal.

The acquittals are generally considered to have triggered the 1992 Los Angeles riots, in which 53 people were killed, and over two thousand were injured. The riots ended after soldiers from the United States Army National Guard, along with United States Marines from nearby Camp Pendleton, California, were called in to assist local authorities and quell the riots.

On August 4, 1992 a Federal Grand Jury after hearing evidence from federal prosecutors indicted the four officers on charges of violating King's civil rights. The four men were put on trial on February 25, 1993 in the United States District Court for the Central District of California located in downtown Los Angeles. On April 16, 1993 the trial ended with two of the police officers, (Koon and Powell) found guilty, and subsequently imprisoned. The other two officers, (Wind and Briseno) were acquitted.

During the riots, King appeared on television and offered what would later be his famous plea, "Can we all get along?"[4]

Early life

Rodney Glen King was born in Sacramento, California, on April 2, 1965, the son of Ronald King and Odessa King. King grew up in Altadena, California, one of five children.[5][6] King's father, Ronald King, died in 1984[7] at the age of 42.[6]

In November 1989, King robbed a store in Monterey Park, California. He threatened to hit the Korean store owner with an iron bar he was carrying, then hit him with a pole. King stole two hundred dollars in cash during the robbery, and was caught, convicted, and sentenced to two years of imprisonment and released after serving one-year of the sentence.[6]

King had three daughters, one by Carmen Simpson when he was a teenager and one by each wife. Both King's marriages, to Crystal Waters and Danetta, ended in divorce.[7][8]

Incident

High-speed chase

On the night of March 2, 1991, King and two passengers, Bryant Allen and Freddie Helms, were driving west on the Foothill Freeway (Interstate 210) in the San Fernando Valley area of Los Angeles. Prior to driving on the Foothill Freeway, the three men had spent the night watching a basketball game and drinking at a friend's house in Los Angeles.[9] Five hours after the incident, King's blood-alcohol level was found to be slightly under the legal limit, indicating his blood alcohol level was at 0.19 while he was driving, which is more than twice the legal driving limit in California.[10] At 12:30 am, Officers Tim and Melanie Singer, who were husband-and-wife members of the California Highway Patrol, noticed King's car speeding on the freeway. The officers pursued King, and the pursuit attained high speeds, while King refused to pull over.[11][12] King would later admit he attempted to outrun the police at dangerously high speeds because a charge of driving under the influence would violate his parole for a previous robbery conviction.[13]

King exited the freeway and the pursuit continued through residential surface streets, at speeds ranging from 55 to 80 miles per hour. [14][15] By this point, several police cars and a police helicopter had joined the pursuit. After approximately eight miles, officers cornered King in his car. The first five LAPD officers to arrive at the scene were Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Theodore Briseno, and Rolando Solano.

Confrontation

Officer Tim Singer ordered King and his two passengers to exit the vehicle and lie face down on the ground. King's two passengers complied and were taken into custody without incident.[9] King remained in the car. When he finally did emerge, he acted bizarrely, giggling, patting the ground, and waving to the police helicopter overhead.[15] King then grabbed his buttocks which Officer Melanie Singer took to mean King reaching for a weapon.[16] She drew her pistol and pointed it at King, ordering him to lie on the ground. King eventually complied, and Singer approached, gun drawn, preparing to effect an arrest.

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (October 2012) |

At that point LAPD Sergeant Stacey Koon, the ranking office on scene, told Singer that LAPD was taking tactical command of the situation. He ordered all officers to holster their weapons.[citation needed] LAPD officers are taught not to approach a suspect with a drawn gun, as there is a risk that a suspect may gain control of it if an officer gets too close.[17] Koon then ordered the four other LAPD officers at the scene, Briseno, Powell, Solano, and Wind, to subdue and handcuff King using a technique called a "swarm." This involves multiple officers grabbing a suspect with empty hands, in order to quickly overcome potential resistance. As the officers attempted to restrain King, King resisted, standing to remove Officers Powell and Briseno from his back. Koon ordered the officers to fall back.[citation needed] The officers later testified that they believed King was under the influence of the dissociative drug phencyclidine (PCP),[18] although King's toxicology tested negative for the drug.[19]

Beating with batons: events on the Holliday video

The point at which Rodney King was struck by Koon's Taser is the approximate start of the George Holliday videotape of the incident. In the tape, King is seen on the ground. He rises and moves toward Powell.[20] Taser wire can be seen in King's body. As King moves forward, Officer Powell strikes King with his baton. The blow strikes King in the head, and King is knocked to the ground.[21] Powell strikes King several more times with his baton. Briseno moves in, attempting to stop Powell from striking again, and Powell stands back. Koon reportedly said, "That's enough." Rodney King then rises again, to his knees, Powell and Wind are then seen hitting King with their batons.[22]

Koon acknowledged ordering the continued use of batons, directing Powell and Wind to strike King with "power strokes." According to Koon, Powell and Wind used "bursts of power strokes, then backed off." In the videotape, King continues to try and stand again. Koon orders the officers to "hit his joints, hit the wrists, hit his elbows, hit his knees, hit his ankles."[22] After a recorded 56 baton blows and six kicks, several officers again "swarm" King, and place him in handcuffs and cordcuffs, restraining his arms and legs. King is dragged on his abdomen to the side of the road to await the arrival of emergency medical rescue.[22]

George Holliday's videotape of the incident was shot from his apartment near the intersection of Foothill Blvd and Osborne St. in Lake View Terrace. He contacted the police about his videotape of the incident but was ignored.[citation needed] He then went to KTLA television with his videotape, which broadcast it in its entirety.[23] The footage became an instant media sensation. Portions of it were aired numerous times, and it "turned what would otherwise have been a violent, but soon forgotten, encounter between the Los Angeles police and an uncooperative suspect into one of the most widely watched and discussed incidents of its kind."[24]

The Holliday video of the Rodney King arrest is a fairly early example of modern sousveillance, where private citizens, assisted by increasingly sophisticated, affordable video equipment, record significant, sometimes historical events. Several "copwatch" organizations subsequently appeared throughout the United States, purportedly to safeguard against police abuse, including an umbrella group, October 22 Coalition to Stop Police Brutality.[25]

Post-arrest events

King was taken to Pacifica Hospital immediately after his arrest, where he was shown to have suffered a fractured facial bone, a broken right ankle, and numerous bruises and lacerations.[26] In a negligence claim filed with the city, King alleged he had suffered "11 skull fractures, permanent brain damage, broken [bones and teeth], kidney damage [and] emotional and physical trauma".[27] Blood and urine samples taken from King five hours after his arrest showed that he would be intoxicated under California law. The tests also showed traces of marijuana (26 ng/ml), but no indication of any other illegal drug.[27] Pacifica Hospital nurses reported that the officers who accompanied King (including Wind) openly joked and bragged about the number of times King had been hit.[28] King sued the city, settling for $3.8 million.[29]

The officers

The Los Angeles district attorney charged officers Koon, Powell, Briseno and Wind with use of excessive force. Sergeant Koon, while he did not strike King, only having deployed the Taser, was, as the supervisory officer at the scene, charged with, "willfully permitting and failing to take action to stop the unlawful assault."

The California Court of Appeals removed the initial judge, Bernard Kamins, after it was proved Kamins told prosecutors, "You can trust me." The Court also granted a change of venue to Simi Valley in neighboring Ventura County, citing potential contamination due to saturated media coverage.

Though few people at first considered race an important factor in the case, including Rodney King's attorney, Steven Lerman, the sensitizing effect of the Holliday videotape was at the time stirring deep resentment in Los Angeles, as well as other major cities in the United States. The officers' jury consisted of Ventura County residents: ten white; one Latino; one Asian. Prosecutor Terry White was African American. On April 29, 1992, the jury acquitted three of the officers, but could not agree on one of the charges against Powell.[9]

Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley said, "The jury's verdict will not blind us to what we saw on that videotape. The men who beat Rodney King do not deserve to wear the uniform of the L.A.P.D."[30] President George H. W. Bush said, "Viewed from outside the trial, it was hard to understand how the verdict could possibly square with the video. Those civil rights leaders with whom I met were stunned. And so was I and so was Barbara and so were my kids."[31]

Los Angeles riots and the aftermath

The acquittals are considered to have triggered the Los Angeles riots of 1992. By the time the police, the U.S. Army, Marines and National Guard restored order, the riots had caused 53 deaths, 2,383 injuries, more than 7,000 fires, damage to 3,100 businesses, and nearly $1 billion in financial losses. Smaller riots occurred in other cities such as San Francisco, Las Vegas in neighboring Nevada and as far east as Atlanta, Georgia. A minor riot erupted on Yonge St., in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, as a result of the acquittals.

Federal trial of officers

After the riots, the United States Department of Justice reinstated the investigation and obtained an indictment of violations of federal civil rights against the four officers in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. The federal trial focused more on the evidence as to the training of officers instead of just relying on the videotape of the incident. On March 9 of the 1993 trial, King took the witness stand and described to the jury the events as he remembered them.[32] The jury found Officer Laurence Powell and Sergeant Stacey Koon guilty, and they were subsequently sentenced to 32 months in prison, while Timothy Wind and Theodore Briseno were acquitted of all charges.[9]

Later life

King successfully sued the city of Los Angeles in a federal civil rights case. The court jury awarded King $3.8 million and awarded King's attorneys $1.7 million in statutory attorney’s fees, which were in addition to the $3.8 million. King's lawyer, Stephen Lerman, distributed the attorney’s fees to the lawyers who worked on King's behalf. King then sued Lerman for legal malpractice claiming King was entitled to those attorney’s fees instead of his lawyers. Lerman successfully defended himself in the action by having the case dismissed on summary judgment, which was affirmed on appeal.

King continued to get into trouble after the 1991 incident. On August 21, 1993, he crashed his car into a block wall in downtown Los Angeles.[33] He was convicted of driving under the influence of alcohol, fined, entered an alcohol rehabilitation program and was placed on probation. In July 1995, he was arrested by Alhambra police, after hitting his wife with his car, knocking her to the ground. He was sentenced to 90 days in jail after being convicted of hit and run.[34] King invested a portion of his settlement in a record label, Straight Alta-Pazz Records, which went under.[35] On August 27, 2003, King was arrested again for speeding and running a red light while under the influence of alcohol. He failed to yield to police officers and slammed his vehicle into a house, breaking his pelvis.[36] On November 29, 2007, while riding home on his bicycle, King was shot in the face, arms, and back with pellets from a shotgun. He reported that it was done by a man and a woman who demanded his bicycle and shot him when he rode away.[34] Police described the wounds as looking like they came from birdshot, but said King offered few details about the suspects.

In May 2008, King checked into the Pasadena Recovery Center in Pasadena, California, where he filmed as a cast member of the second season of Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew, which premiered in October 2008. Dr. Drew Pinsky, who runs the facility, showed concern for King's lifestyle and said that King would die unless his addiction were treated.[37] He also appeared on Sober House, a Celebrity Rehab spin-off focusing on a sober living environment, which aired in early 2009. Both shows filmed King's quest not only to achieve sobriety, but to reestablish a relationship with his family, which had been severely damaged due to his drinking and law-breaking.[38]

During his time on Celebrity Rehab and Sober House, King worked on his addiction and on the lingering trauma of the beating. He and Pinsky retraced his path from the night of his beating, eventually reaching the spot where it happened, the site of the Children's Museum of Los Angeles.[39]

King won[40] a celebrity boxing match against ex-Chester City (Delaware County, Pennsylvania) police officer Simon Aouad on Friday, September 11, 2009, at the Ramada Philadelphia Airport in Essington, Pennsylvania.[41]

In 2009, King and other Celebrity Rehab alumni appeared as panel speakers to a new group of addicts at the Pasadena Recovery Center, marking 11 months of sobriety for him. His appearance was aired in the third season episode "Triggers".[42]

In surprising news on September 9, 2010, it was confirmed that King was going to marry Cynthia Kelley, who had been a juror in the civil suit King brought against the City of Los Angeles when he was awarded $3.8 million.[3]

On March 3, 2011, the 20th anniversary of the beating, King was stopped by LAPD for driving erratically. He was issued a citation for driving with an expired license.[43][44][45] This arrest led to his February 2012 misdemeanor conviction for reckless driving.[46]

On April 12, 2012, King released a statement to the media regarding the Trayvon Martin shooting. King said he was "grieving for Trayvon Martin" and stated how the scream on the audio of George Zimmerman's 911 call reminded him of his own screaming during his beating by the LAPD.[47]

The BBC quoted King commenting on his legacy. "Some people feel like I'm some kind of hero,". "Others hate me. They say I deserved it. Other people, I can hear them mocking me for when I called for an end to the destruction, like I'm a fool for believing in peace."[48]

Death

On June 17, 2012, King's fiancée Cynthia Kelly found him lying at the bottom of his swimming pool.[49] Police in Rialto received a 911 call from Kelly at about 5:25 a.m. (PT).[50][51] Responding officers found King at the bottom of the pool, removed him, and attempted to revive him. He was transferred by ambulance to Arrowhead Regional Medical Center in Colton, California. King was pronounced dead at the hospital at 6:11 a.m. The Rialto Police Department began a standard drowning investigation and stated that there did not appear to be any foul play. On August 23, 2012, King's autopsy results were released. It stated he died of accidental drowning, and that alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana were found in his blood and were contributing factors.[52]

See also

Notes

- ^ CNN Wire Staff (June 17, 2012). "Rodney King dead at 47". CNN. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Rodney King Height". Talltask.com. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ a b "Rodney King to marry juror from LA police beating case". BBC News. September 9, 2010.

- ^ Video of Rodney King's Plea during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots From YouTube. Retrieved June 18, 2012. The line has been often misquoted as, "Can we all just get along?" King did not use the word "just" in his original statement.

- ^ "Rodney King, L.A. police beating victim, dies". San Francisco Chronicle. June 18, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c Phil Reeves (February 21, 1993). "Profile: An icon, anxious and shy: Rodney King - As he awaits a new trial of the police who beat him, Rodney King has become a hero, a demon, and a gold mine". The Independent. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "Obits, Rodney King". The Telegraph. United Kingdom. June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Rodney King". BuddyTV.com. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Linder, Douglas (December 2001). "The Rodney King Beating Trials". JURIST. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: p. 39.

- ^ An Account of the Los Angeles Police Officers' Trials(The Rodney King Beating Case)

- ^ Koon v. United States 518 U.S. 81 (1996)

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: p. 43.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard W.; Egan, Timothy (March 18, 1991). "Seven Minutes in Los Angeles – A special report.; Videotaped Beating by Officers Puts Full Glare on Brutality Issue". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Whitman, David (May 23, 1993). "The Untold Story of the LA Riot". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: p. 27.

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: p. 28.

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: [page needed]

- ^ Cannon, Lou (March 16, 1993). "Prosecution Rests Case in Rodney King Beating". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ "Chapter 1: The Rodney King Beating". Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department: p. 6. 1991.

- ^ "Chapter 1: The Rodney King Beating". Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department: p. 7. 1991. "The blow hit King's head, and he went down immediately."

- ^ a b c "Chapter 1: The Rodney King Beating". Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department: p. 7. 1991.

- ^ Michael Goldstein (February 19, 2006). "The Other Beating: Fifteen years after his video of Rodney King reached the world, George Holliday looks back on how that night has hurt him". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ "The Holliday Videotape, George Holliday Video of King Beating".

- ^ PBS.org and the ACLU [1] draw connections between the event and the subsequent activities of many organizations.

- ^ Cannon. Official Negligence: p. 205.

- ^ a b "Chapter 1: The Rodney King Beating". Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department: p. 8. 1991.

- ^ "Chapter 1: The Rodney King Beating". Report of the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department: p. 15. 1991.

- ^ "Rodney King Is Arrested After a Fight at His Home". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. September 30, 2005. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (April 30, 1992). "The Police Verdict; Los Angeles Policemen Acquitted in Taped Beating". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ Fiske, John (March 1, 1996). Media Matters: Race and Gender in U.S. Politics (paperback) (Paperback). Univ Of Minnesota Press; Revised edition. p. 188. ISBN 9780816624638.

Bush on LA, extracts from his speech to the nation

- ^ Mydans, Seth (March 10, 2003). "Rodney King Testifies on Beating: 'I Was Just Trying to Stay Alive'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Rodney King's Wife Files Petition for Divorce". Los Angeles Times. November 29, 1995. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Reston, Maeve (November 30, 2007). "Rodney King shot while riding bike". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ Madison Gray (2007). "The L.A. Riots: 15 Years After Rodney King". Time.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Rodney King slams SUV into house, breaks pelvis". CNN. April 16, 2003. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007.

- ^ TV Guide: page 8. June 23, 2008.

- ^ "Sober House Will Follow Celebrity Rehab Cast, Andy Dick in Sober Living". RealityBlurred.com. December 19, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Elise. "Rodney King Forgives Officers Who Beat Him — LAist". Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- ^ "Rodney King Fight Results". BittenAndBound.com. September 12, 2009.

- ^ Stamm, Dan (August 19, 2009). "No Plan to 'Get Along' When Rodney King Takes on Former Cop". NBC Philadelphia. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew Episode 3.6 ("Triggers") VH1; February 11, 2010

- ^ "Rodney King stopped after traffic violation, police say". Los Angeles Times. March 4, 2011.

- ^ Rodney King once again runs afoul of the law, cited for expired license in Arcadia - Pasadena Star-News[dead link]

- ^ Hartley-Parkinson, Richard (July 13, 2011). "Rodney King pulled over by police almost 20 years to the day since his arrest and /CRIME/07/12/california.rodney.king.arrest/index.html". Daily Mail. London: CNN.

- ^ Wilson, Stan (April 12, 2012). "Rodney King pleads for calm in Trayvon Martin case". CNN. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ "Rodney King: "I'm grieving for Trayvon Martin"". Los Angeles Times. April 12, 2012.

- ^ "Los Angeles riots: Rodney King funeral held". BBC News. July 1, 2012.

- ^ "Rodney King found dead". CBS News. June 17, 2012.

- ^ "911 call reveals frantic moments, fiancee's pleas after finding Rodney King submerged in pool". The Washington Post. AP. June 18, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ Jennifer Medina (June 17, 2012). "Police Beating Victim Who Asked 'Can We All Get Along?'". The New York Times.

- ^ Wilson, Stan (August 23, 2012). "Autopsy attributes Rodney King's death to drowning". CNN. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

References

- The "Rodney King Beating video" is under copyright. For authorization contact www.rodneykingvideo.com.ar

- Cannon, Lou (1999). Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the riots changed Los Angeles and the LAPD. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813337258. OCLC 42852365.

Further reading

- King, Rodney (2012). The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption. New York: HarperOne. ISBN 9780062194435. OCLC 761856270.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) King's autobiography. - Koon, Stacey C. (1992). Presumed Guilty: The Tragedy of the Rodney King Affair. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway. ISBN 9780895265074. OCLC 26553041.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Rodney King at IMDb

- Rodney King collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Rodney King collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Rodney King's Arrest Record

- Rodney King news and commentary at CNN

- Rodney King: 17 Years After The Riots", Laist.com

- Kavanagh, Jim. "Rodney King, 20 years later." CNN. March 3, 2011.

- Rodney King at Find a Grave

- 1965 births

- 2012 deaths

- Accidental deaths in California

- African-American people

- American people convicted of robbery

- Citizen journalism

- Deaths by drowning

- Drug-related deaths in California

- History of Los Angeles, California

- Los Angeles Police Department

- Participants in American reality television series

- People from Rialto, California

- People from Sacramento, California

- Victims of police brutality

- American construction businesspeople

- People from Altadena, California