Central dogma of molecular biology: Difference between revisions

→General transfers of biological sequential information: Switched 2 cells in the table to make things a bit more logical |

Undid revision 533735787 by 89.83.73.89 (talk) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| DNA → RNA || RNA → RNA || protein → RNA |

| DNA → RNA || RNA → RNA || protein → RNA |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| RNA → protein || DNA → protein || protein → protein |

||

|} |

|} |

||

Revision as of 19:29, 18 January 2013

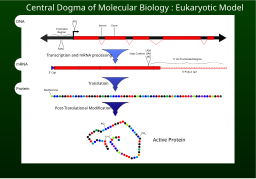

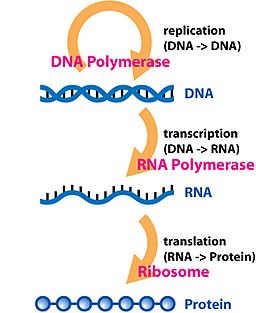

The central dogma of molecular biology describes the flow of genetic information within a biological system. It was first stated by Francis Crick in 1958[1] and re-stated in a Nature paper published in 1970:[2]

- The central dogma of molecular biology deals with the detailed residue-by-residue transfer of sequential information. It states that such information cannot be transferred back from protein to either protein or nucleic acid.

Or, as Marshall Nirenberg said, "DNA makes RNA makes protein."[3]

To appreciate the significance of the concept, note that Crick had misapplied the term "dogma" in ignorance. In evolutionary or molecular biological theory, either then or subsequently, Crick's proposal had nothing to do with the correct meaning of "dogma". He subsequently documented this error in his autobiography.

The dogma is a framework for understanding the transfer of sequence information between sequential information-carrying biopolymers, in the most common or general case, in living organisms. There are 3 major classes of such biopolymers: DNA and RNA (both nucleic acids), and protein. There are 3×3 = 9 conceivable direct transfers of information that can occur between these. The dogma classes these into 3 groups of 3: 3 general transfers (believed to occur normally in most cells), 3 special transfers (known to occur, but only under specific conditions in case of some viruses or in a laboratory), and 3 unknown transfers (believed never to occur). The general transfers describe the normal flow of biological information: DNA can be copied to DNA (DNA replication), DNA information can be copied into mRNA (transcription), and proteins can be synthesized using the information in mRNA as a template (translation).[2]

Biological sequence information

The biopolymers that comprise DNA, RNA and amino acids are linear polymers (i.e.: each monomer is connected to at most two other monomers). The sequence of their monomers effectively encodes information. The transfers of information described by the central dogma are faithful, deterministic transfers, wherein one biopolymer's sequence is used as a template for the construction of another biopolymer with a sequence that is entirely dependent on the original biopolymer's sequence.

General transfers of biological sequential information

Table of the 3 classes of information transfer suggested by the dogma General Special Unknown DNA → DNA RNA → DNA protein → DNA DNA → RNA RNA → RNA protein → RNA RNA → protein DNA → protein protein → protein

Transcription

Transcription is the process by which the information contained in a section of DNA is transferred to a newly assembled piece of messenger RNA (mRNA). It is facilitated by RNA polymerase and transcription factors. In eukaryotic cells the primary transcript (pre-mRNA) must be processed further in order to ensure translation. This normally includes a 5' cap, a poly-A tail and splicing. Alternative splicing can also occur, which contributes to the diversity of proteins any single mRNA can produce.

Translation

Eventually, this mature mRNA finds its way to a ribosome, where it is translated. In prokaryotic cells, which have no nuclear compartment, the process of transcription and translation may be linked together. In eukaryotic cells, the site of transcription (the cell nucleus) is usually separated from the site of translation (the cytoplasm), so the mRNA must be transported out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it can be bound by ribosomes. The mRNA is read by the ribosome as triplet codons, usually beginning with an AUG (adenine−uracil−guanine), or initiator methionine codon downstream of the ribosome binding site. Complexes of initiation factors and elongation factors bring aminoacylated transfer RNAs (tRNAs) into the ribosome-mRNA complex, matching the codon in the mRNA to the anti-codon on the tRNA, thereby adding the correct amino acid in the sequence encoding the gene. As the amino acids are linked into the growing peptide chain, they begin folding into the correct conformation. Translation ends with a UAA, UGA, or UAG stop codon. The nascent polypeptide chain is then released from the ribosome as a mature protein. In some cases the new polypeptide chain requires additional processing to make a mature protein. The correct folding process is quite complex and may require other proteins, called chaperone proteins. Occasionally, proteins themselves can be further spliced; when this happens, the inside "discarded" section is known as an intein.

DNA replication

As the final step in the central dogma, DNA replication must occur in order to faithfully transmit genetic material to the progeny of any cell or organism. Replication is carried out by a complex group of proteins called the replisome which consists of a helicase that unwinds the superhelix as well as the double-stranded DNA helix, and DNA polymerase and its associated proteins, which insert new nucleic in a sequence specific manner. This process typically takes place during S phase of the cell cycle.

Special transfers of biological sequential information

Reverse transcription

Reverse transcription is the transfer of information from RNA to DNA (the reverse of normal transcription). This is known to occur in the case of retroviruses, such as HIV, as well as in eukaryotes, in the case of retrotransposons and telomere synthesis.

RNA replication

RNA replication is the copying of one RNA to another. Many viruses replicate this way. The enzymes that copy RNA to new RNA, called RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, are also found in many eukaryotes where they are involved in RNA silencing.[4] RNA editing, in which an RNA sequence is altered by a complex of proteins and a "guide RNA", could also be considered an RNA-to-RNA transfer.

Direct translation from DNA to protein

Direct translation from DNA to protein has been demonstrated in a cell-free system (i.e. in a test tube), using extracts from E. coli that contained ribosomes, but not intact cells. These cell fragments could express proteins from foreign DNA templates, and neomycin was found to enhance this effect.[5][6]

Transfers of information not explicitly covered in the theory

Posttranslational modification

Protein amino acid sequence can be edited after translation by various enzymes. This is a case of protein affecting protein sequence, not explicitly covered by the central dogma.

Inteins

An intein is a "parasitic" segment of a protein that is able to excise itself from the chain of amino acids as they emerge from the ribosome and rejoin the remaining portions with a peptide bond. This is a case of a protein affecting its own primary sequence encoded originally by the DNA of a gene. Additionally, most inteins contain a homing endonuclease or HEG domain which is capable of finding a copy of the parent gene not containing the intein nucleotide sequence. On contact with the intein-free copy, the HEG domain initiates the DNA double-stranded break repair mechanism. This process causes the intein sequence to be copied from the original source gene to the intein-free gene. This is an example of protein directly editing DNA sequence, as well as increasing the sequence's heritable propagation.

Methylation

Variation in methylation states of DNA can alter gene expression levels significantly. Methylation variation usually occurs through the action of DNA methylases. When the change is heritable, it is considered epigenetic. When the change in information status is not heritable, it would be a somatic epitype. The effective information content has been changed by means of the actions of a protein or proteins on DNA, but the primary DNA sequence is not altered.

Prions

Prions are proteins that propagate themselves by making conformational changes in other molecules of the same type of protein. This change affects the behaviour of the protein. In fungi this change happens from one generation to the next, i.e. Protein → Protein. While this represents a transfer of information, prion interactions leave the sequence of the protein unchanged, and so are not technically considered an exception to the central dogma.

Natural genetic engineering

James A. Shapiro argues that a superset of these examples should be classified as natural genetic engineering and are sufficient to falsify the central dogma. While Shapiro has received a respectful hearing for his view, his critics have not been convinced that his reading of the central dogma is in line with what Crick intended.[7] [8]

Use of the term "dogma"

In his autobiography, What Mad Pursuit, Crick wrote about his choice of the word dogma and some of the problems it caused him:

"I called this idea the central dogma, for two reasons, I suspect. I had already used the obvious word hypothesis in the sequence hypothesis, and in addition I wanted to suggest that this new assumption was more central and more powerful. ... As it turned out, the use of the word dogma caused almost more trouble than it was worth.... Many years later Jacques Monod pointed out to me that I did not appear to understand the correct use of the word dogma, which is a belief that cannot be doubted. I did apprehend this in a vague sort of way but since I thought that all religious beliefs were without foundation, I used the word the way I myself thought about it, not as most of the world does, and simply applied it to a grand hypothesis that, however plausible, had little direct experimental support."

Similarly, Horace Freeland Judson records in The Eighth Day of Creation:[9]

"My mind was, that a dogma was an idea for which there was no reasonable evidence. You see?!" And Crick gave a roar of delight. "I just didn't know what dogma meant. And I could just as well have called it the 'Central Hypothesis,' or — you know. Which is what I meant to say. Dogma was just a catch phrase."

See also

References

- ^ Crick, F.H.C. (1958): On Protein Synthesis. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. XII, 139-163. (pdf, early draft of original article)

- ^ a b Crick, F (1970). "Central dogma of molecular biology" (PDF). Nature. 227 (5258): 561–3. Bibcode:1970Natur.227..561C. doi:10.1038/227561a0. PMID 4913914.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leavitt, Sarah A. (June 2010). "Deciphering the Genetic Code: Marshall Nirenberg". Office of NIH History.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ahlquist P (2002). "RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing". Science. 296 (5571): 1270–3. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1270A. doi:10.1126/science.1069132. PMID 12016304.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ B. J. McCarthy and J. J. Holland (September 15, 1965). "Denatured DNA as a Direct Template for in vitro Protein Synthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. 54 (3): 880–886. Bibcode:1965PNAS...54..880M. doi:10.1073/pnas.54.3.880. PMC 219759. PMID 4955657.

- ^ .T. Uzawa, A. Yamagishi, T. Oshima (2002-04-09). "Polypeptide Synthesis Directed by DNA as a Messenger in Cell-Free Polypeptide Synthesis by Extreme Thermophiles, Thermus thermophilus HB27 and Sulfolobus tokodaii Strain 7". The Journal of Biochemistry. 131 (6): 849–853. PMID 12038981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilkins, Adam S. (2012). "(Review) Evolution: A View from the 21st Century". Genome Biology and Evolution. doi:10.1093/gbe/evs008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moran, Laurence A (2011). "(Review) Evolution: A View from the 21st Century". Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 32.3 (9): 1–4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Horace Freeland Judson (1996). "Chapter 6: My mind was, that a dogma was an idea for which there was no reasonable evidence. You see?!". The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology (25th anniversary edition). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-477-7.