Bison hunting: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Lead too short}} |

Metricmike (talk | contribs) →19th century bison hunts and near extinction: It's an approximation of distance! |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, [[cartridge (firearms)|cartridge]] reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as [[Buffalo Bill|Buffalo Bill Cody]], killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his own count. A good hide could bring $3 in [[Dodge City, Kansas|Dodge City]], [[Kansas]], and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day. |

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, [[cartridge (firearms)|cartridge]] reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as [[Buffalo Bill|Buffalo Bill Cody]], killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his own count. A good hide could bring $3 in [[Dodge City, Kansas|Dodge City]], [[Kansas]], and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day. |

||

The hunter would customarily locate the herd in the early morning, and station himself about |

The hunter would customarily locate the herd in the early morning, and station himself about 100 yards/meters from it, shooting the animals broadside through the lungs. Head shots were not preferred as the soft lead bullets would often flatten and fail to penetrate the skull, especially if mud was matted on the head of the animal. The bison would continue to drop until either the herd sensed danger and stampeded or perhaps a wounded animal attacked another, causing the herd to disperse. If done properly a large number of bison would be felled at one time. Following up were the skinners, who would drive a spike through the nose of each dead animal with a [[sledgehammer]], hook up a horse team, and pull the hide from the carcass. The hides were dressed, prepared, and stacked on the wagons by other members of the organization. |

||

For a decade from 1873 on there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by American Indians or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. It was said that the [[.50-90 Sharps|Big .50s]] were fired so much that hunters needed at least two rifles to let the barrels cool off; The Fireside Book of Guns reports they were sometimes quenched in the winter snow. Dodge City saw railroad cars sent East filled with stacked hides. |

For a decade from 1873 on there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by American Indians or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. It was said that the [[.50-90 Sharps|Big .50s]] were fired so much that hunters needed at least two rifles to let the barrels cool off; The Fireside Book of Guns reports they were sometimes quenched in the winter snow. Dodge City saw railroad cars sent East filled with stacked hides. |

||

Revision as of 00:44, 25 February 2013

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2013) |

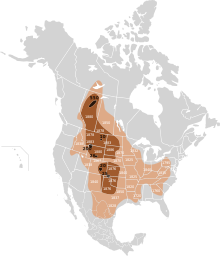

Buffalo hunting (hunting of the American bison) was an activity fundamental to the Plains Indian tribes of the United States, which was later adopted by American professional hunters, leading to the near-extinction of the species.

Prehistoric and Native hunting

The American bison is a relative newcomer to North America, having originated in Eurasia and migrated over the Bering Strait.[1] About 10,000 years ago it replaced the steppe bison (Bison priscus), a previous immigrant that was much larger. It is thought that the long-horned bison became extinct due to a changing ecosystem and hunting pressure following the development of the Clovis point and related technology, and improved hunting skills. During this same period, other megafauna vanished and were replaced to some degree by immigrant Eurasian animals that were better adapted to predatory humans. The American bison, technically a dwarf form, was one of these animals. The American bison's ancestor, Bison antiquus, was a breed with longer horns than the modern North American animal, but was not the same as the steppe bison.

Bison were a keystone species, whose grazing pressure was a force that shaped the ecology of the Great Plains as strongly as periodic prairie fires and which were central to the lifestyle of American Indians of the Great Plains. However, there is now some controversy over their interaction. "Hernando De Soto's expedition staggered through the Southeast for four years in the early 16th century and saw hordes of people but apparently did not see a single bison," Charles C. Mann wrote in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Mann discussed the evidence that Native Americans not only created (by selective use of fire) the large grasslands that provided the bison's ideal habitat but also kept the bison population regulated. In this theory, it was only when the original human population was devastated by wave after wave of epidemic (from diseases of Europeans) after the 16th century that the bison herds propagated wildly. In such a view, the seas of bison herds that stretched to the horizon were a symptom of an ecology out of balance, only rendered possible by decades of heavier-than-average rainfall. Other evidence of the arrival circa 1550–1600 in the savannas of the eastern seaboard includes the lack of places which southeast natives named after buffalo.[2][3] Bison were the most numerous single species of large wild mammal on Earth. [1]

What is not disputed is that before the introduction of horses, bison were herded into large chutes made of rocks and willow branches and then stampeded over cliffs. These Buffalo jumps are found in several places in the U.S. and Canada, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. Large groups of people would herd the bison for several miles, forcing them into a stampede that would ultimately drive many animals over a cliff. The large quantities of meat obtained in this way provided the hunters with surplus, which was used in trade. A similar method of hunting was to drive the bison into natural corrals, such as the Ruby site.

To get the optimum use out of the bison, the Native Americans had a specific method of butchery, first identified at the Olsen-Chubbuck archaeological site in Colorado. The method involves skinning down the back in order to get at the tender meat just beneath the surface, the area known as the "hatched area." After the removal of the hatched area, the front legs are cut off as well as the shoulder blades. Doing so exposes the hump meat (in the Wood Bison), as well as the meat of the ribs and the Bison's inner organs. After everything was exposed, the spine was then severed and the pelvis and hind legs removed. Finally, the neck and head were removed as one. This allowed for the tough meat to be dried and made into pemmican.

Later when Plains Indians obtained horses, it was found that a good horseman could easily lance or shoot enough bison to keep his tribe and family fed, as long as a herd was nearby. The bison provided meat, leather, sinew for bows, grease, dried dung for fires, and even the hooves could be boiled for glue.

19th century bison hunts and near extinction

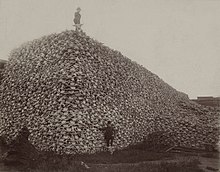

Bison were hunted almost to extinction in the 19th century and were reduced to a few hundred by the mid-1880s. They were hunted for their skins, with the rest of the animal left behind to decay on the ground.[4] After the animals rotted, their bones were collected and shipped back east in large quantities.[4]

The US Army sanctioned and actively endorsed the wholesale slaughter of bison herds.[5] The federal government promoted bison hunting for various reasons, to allow ranchers to range their cattle without competition from other bovines, and primarily to weaken the North American Indian population by removing their main food source and to pressure them onto the reservations.[6] Without the bison, native people of the plains were forced to leave the land or starve to death.

According to historian Pekka Hämäläinen, Native Americans also contributed to the collapse of the bison.[7] By the 1830s the Comanche and their allies on the southern plains were killing about 280,000 bison a year, which was near the limit of sustainability for that region. Firearms and horses, along with a growing export market for buffalo robes and bison meat had resulted in larger and larger numbers of bison killed each year. A long and intense drought hit the southern plains in 1845, lasting into the 1860s, which caused a widespread collapse of the bison herds.[7] In the 1860s, the rains returned and the bison herds recovered to a degree.

The railroad industry also wanted bison herds culled or eliminated. Herds of bison on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time. Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding though hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, bison herds could delay a train for days.[1]

The main reason for the bison's near-demise, much like the actual demise of the Passenger Pigeon, was commercial hunting.

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as Buffalo Bill Cody, killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his own count. A good hide could bring $3 in Dodge City, Kansas, and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day.

The hunter would customarily locate the herd in the early morning, and station himself about 100 yards/meters from it, shooting the animals broadside through the lungs. Head shots were not preferred as the soft lead bullets would often flatten and fail to penetrate the skull, especially if mud was matted on the head of the animal. The bison would continue to drop until either the herd sensed danger and stampeded or perhaps a wounded animal attacked another, causing the herd to disperse. If done properly a large number of bison would be felled at one time. Following up were the skinners, who would drive a spike through the nose of each dead animal with a sledgehammer, hook up a horse team, and pull the hide from the carcass. The hides were dressed, prepared, and stacked on the wagons by other members of the organization.

For a decade from 1873 on there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by American Indians or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. It was said that the Big .50s were fired so much that hunters needed at least two rifles to let the barrels cool off; The Fireside Book of Guns reports they were sometimes quenched in the winter snow. Dodge City saw railroad cars sent East filled with stacked hides.

The building of the railroads through Colorado and Kansas split the bison herd in two parts, the southern herd and the northern herd. The last refuge of the southern herd was in the Texas panhandle.[8]

As the great herds began to wane, proposals to protect the bison were discussed. Cody, among others, spoke in favor of protecting the bison because he saw that the pressure on the species was too great. Yet these proposals were discouraged since it was recognized that the Plains Indians, often at war with the United States, depended on bison for their way of life. In 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant "pocket vetoed" a Federal bill to protect the dwindling bison herds, and in 1875 General Philip Sheridan pleaded to a joint session of Congress to slaughter the herds, to deprive the Indians of their source of food.[9] By 1884, the American Bison was close to extinction.

Resurgence of the Bison

The famous herd of James "Scotty" Philip in South Dakota was one of the earliest reintroductions of bison to North America. In 1899, Phillip purchased a small herd (five of them, including the female) from Dug Carlin, Pete Dupree's brother-in-law, whose son Fred had roped five calves in the Last Big Buffalo Hunt on the Grand River in 1881 and taken them back home to the ranch on the Cheyenne River. Scotty's goal was to preserve the animal from extinction. At the time of his death in 1911 at 53, Philip had grown the herd to an estimated 1,000 to 1,200 head of bison. A variety of privately owned herds had also been established, starting from this population.

Simultaneously, two Montana ranchers, Michel Pablo and Charles Allard, spent more than 20 years assembling one of the largest collections of purebred bison on the continent (by the time of Allard's death in 1896, the herd numbered 300). In 1907, after U.S. authorities declined to buy the herd, Pablo struck a deal with the Canadian government and shipped most of his bison northward to the newly created Elk Island National Park.[9][10] Also, in 1907, the New York Zoological Park sent 15 bison to Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma forming the nucleus of a herd that now numbers 650.[11]

The Yellowstone Park Bison Herd formed naturally from a few bison that remained in the Yellowstone Park area after the great slaughter at the end of the 19th century. Yellowstone National Park is one of the very few areas where wild bison were never completely extirpated. It is the only continuously wild bison herd in the United States.[12] Numbering between 3,000 and 3,500, the Yellowstone Park bison herd is descended from a remnant population of 23 individual bison that survived the mass slaughter of the 19th century by hiding out in the Pelican Valley of Yellowstone Park. In 1902, a captive herd of 21 plains bison was introduced to the Lamar Valley in Yellowstone and managed as livestock until the 1960s, when a policy of natural regulation was adopted by the park.

The Antelope Island bison herd is an isolated bison herd on Utah's Antelope Island, and was founded from 12 animals that came from a private ranch in Texas in the late 1800s. The Antelope Island bison herd fluctuates between 550 and 700, and is one of the largest publicly owned bison herds in the nation. The herd contains some unique genetic traits and has been used to improve the genetic diversity of American bison, however, as is the case with most bison herds, some genes from domestic cattle have been found in the Antelope Island Bison Herd.

The last of the remaining "southern herd" in Texas were saved before extinction in 1876. Charles Goodnight's wife, "Molly" encouraged him to save some of the last relict bison that had taken refuge in the Texas Panhandle. Extremely committed to save this herd, she went as far as to rescue some young orphaned buffaloes and even bottle fed and cared for them until adulthood. By saving these few plains bison, she was able to establish an impressive buffalo herd near the Palo Duro Canyon. Peaking at 250 in 1933, the last of the southern buffalo would become known as the Goodnight herd.[13] The descendants of this southern herd were moved to Caprock Canyons State Park near Quitaque, Texas in 1998.[14]

Many other bison herds are in the process of being created or have been created in state parks and national parks, and on private ranches, with individuals taken from the existing main 'foundation herds'.[15][16][17] An example is the Henry Mountains bison herd in Central Utah which was founded in 1941 with bison that were relocated from Yellowstone National Park. This herd now numbers approximately 400 individuals and in the last decade steps have been taken to expand this herd to the mountains of the Book Cliffs, also in Utah.

One of the largest privately owned herds, numbering 2,500, in the US is on the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma which is owned by the Nature Conservancy. Ted Turner is the largest private owner of bison with about 50,000 on several different ranches.[18]

The current American bison population has been growing rapidly, and is estimated at 350,000 compared to an estimated 60 to 100 million in the mid-19th century.[citation needed] Most current herds, however are genetically polluted or partly crossbred with cattle.[19][20][21][22] Today there are only four genetically unmixed, free roaming, public bison herds and only two that are also free of brucellosis: the Henry Mountains Bison Herd and the Wind Cave Bison Herd. A founder population of 16 animals from the Wind Cave bison herd was re-established in Montana in 2005 by the American Prairie Foundation. The herd now numbers near 100 and roams a 14,000-acre (57 km2) grassland expanse on American Prairie Reserve.

The end of the ranching era and the onset of the natural regulation era set into motion a chain of events that have led to the bison of Yellowstone Park migrating to lower elevations outside the park in search of winter forage. The presence of wild bison in Montana is perceived as a threat to many cattle ranchers, who fear that the small percentage of bison that carry brucellosis will infect livestock and cause cows to abort their first calves. However, there has never been a documented case of brucellosis being transmitted to cattle from wild bison. The management controversy that began in the early 1980s continues to this day, with advocacy groups arguing that the herd should be protected as a distinct population segment under the Endangered Species Act.

Modern hunting

Hunting of wild bison is legal in some states and provinces where public herds require culling to maintain a target population. In Alberta, where one of only two continuously wild herds of bison exist in North America at Wood Buffalo National Park, bison are hunted to protect disease-free public (reintroduced) and private herds of bison.

In Montana, a public hunt was reestablished in 2005, with 50 permits being issued. The Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Commission increased the number of tags to 140 for the 2006/2007 season. Advocacy groups claim that it is premature to reestablish the hunt, given the bison's lack of habitat and wildlife status in Montana.

Though the number is usually several hundred, up to more than a thousand bison from the Yellowstone Park Bison Herd have been killed in some years when they wander north from the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone National Park into private and state lands of Montana. This hunting is done because of fears that the Yellowstone bison, which are often infected with Brucellosis will spread that disease to local domestic cattle.

The State of Utah maintains two bison herds. Bison hunting in Utah is permitted in both the Antelope Island Bison Herd and the Henry Mountains Bison Herd though the licenses are limited and tightly controlled. A Game Ranger is also generally sent out with any hunters to help them find and select the right bison to kill. In this way, the hunting is used as a part of the wildlife management strategy and to help cull less desirable individuals.

Every year all the bison in the Antelope Island Bison Herd are rounded up to be examined and vaccinated. Then most of them are turned loose again, to wander Antelope Island but approximately 100 bison are sold at an auction, and hunters are allowed to kill a half dozen bison. This hunting takes place on Antelope Island in December each year. Fees from the hunters are used to improve Antelope Island State Park and to help maintain the bison herd.

Hunting is also allowed every year in the Henry Mountains Bison Herd in Utah. The Henry Mountains herd has sometimes numbered up to 500 individuals but the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources has determined that the carrying capacity for the Henry Mountains Bison Herd is 325 individuals. Some of the extra individuals have been transplanted, but most of them are not transplanted or sold, so hunting is the major tool used to control their population. "In 2009, 146 public once-in-a-lifetime Henry Mountain bison hunting permits were issued."[23] Most years, 50 to 100 licenses are issued to hunt bison in the Henry Mountains.

Bison were also reintroduced to Alaska in 1928, and both domestic and wild herds subsist in a few parts of the state.[24][25] The state grants limited permits to hunt wild bison each year.[26][27]

The bison is one of the few North American large game animals that can be hunted year round, though hunters prefer to hunt it at certain times of the year to achieve desired appearances of the coat.

In 2002 the United States government donated some buffalo calves from South Dakota and Colorado to the Mexican government for the reintroduction of bison to Mexico's nature reserves. These reserves included El Uno Ranch at Janos and Santa Helena Canyon, Chihuahua, and Boquillas del Carmen, Coahuila, which is located on the southern shore of the Rio Grande and the grasslands bordering Texas and New Mexico.[28]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Sheppard Software, Bison [1]

- ^ Rostlund, Erhard (1 December 1960). "# The Geographic Range of the Historic Bison in the Southeast". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 50 (4). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 395–407. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1960.tb00357.x. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2561275.

- ^ Juras, Philip (1997). "The Presettlement Piedmont Savanna: A Model For Landscape Design and Management". Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ^ a b Records, Laban (1995). Cherokee Outlet Cowboy: Recollectioons of Laban S. Records. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2694-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hanson, Emma I. Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian People. Cody, WY: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 2007: 211.

- ^ Moulton, M (1995). Wildlife issues in a changing world, 2nd edition. CRC Press.

- ^ a b Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 294–299, 313. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- ^ Page 9 T. Lindsay Baker, Billy R. Harrison, B. Byron Price, Adobe Walls

- ^ a b Bergman, Brian (2004-02-16). "Bison Back from Brink of Extinction". Maclean's. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

For the sake of lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated.

- ^ Hearst Magazines (January 1931). Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 1–. ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ American Bison, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Accessed Dec 3, 2010

- ^ Staff (December/January2012). "Restoring a Prairie Icon". National Wildlife. 50 (1). National Wildlife Federation: 20–25.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ John Cornyn, The Winkler Post, Molly Goodnight [2]

- ^ Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine

- ^ National Bison Range – Dept of the Interior Recovery Activities. Recovery.doi.gov. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ American Bison Society > Home. Americanbisonsocietyonline.org. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ Where the Buffalo Roam. Mother Jones. Retrieved on September 16, 2011.

- ^ "accessed Dec 3, 2010". Tedturner.com. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (January 19, 2007). "Strands of undesirable DNA roam with buffalo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Polzhien, R.O. (1995). "Bovine mtDNA Discovered in North American Bison Populations". Conservation Biology. 9 (6): 1638–43. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09061638.x. JSTOR 2387208.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Halbert, ND; Ward, TJ; Schnabel, RD; Taylor, JF; Derr, JN (2005). "Conservation genomics: disequilibrium mapping of domestic cattle chromosomal segments in North American bison populations" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 14 (8): 2343–2362. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02591.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 15969719. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Halbert, Natalie Dierschke (2003). "The utilization of genetic markers to resolve modern management issues in historic bison populations: implications for species conservation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 09 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Once-In-A-Lifetime Permits" (PDF). Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Alaska Hunting and Trapping Information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Wc.adfg.state.ak.us. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska Hunting and Trapping Information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Wc.adfg.state.ak.us. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska Department of Fish and Game". Adfg.state.ak.us. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ "Alaska bison hunt near Delta Junction". Outdoorsdirectory.com. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ staff (March 3, 2010). "Restoring North America's Wild Bison to Their Home on the Range". Ens-newswire.com. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

Further reading

- Branch, E. Douglas. The Hunting of the Buffalo (1929, new ed. University of Nebraska Press, 1997), classic history online edition

- Barsness, Larry. Heads, Hides and Horns: The Compleat Buffalo Book. (Texas Christian University Press, 1974)

- Dary David A. The Buffalo Book. (Chicago: Swallow Press, 1974)

- Dobak, William A. (1996). "Killing the Canadian Buffalo, 1821–1881". Western Historical Quarterly. 27 (1): 33–52. doi:10.2307/969920.

- Dobak, William A. (1995). "The Army and the Buffalo: A Demur". Western Historical Quarterly. 26: 197–203. JSTOR 970189.

- Flores, Dan (1991). "Bison Ecology and Bison Diplomacy: The Southern Plains from 1800 to 1850". Journal of American History. 78 (2): 465–85. doi:10.2307/2079530. JSTOR 2079530.

- Gard, Wayne. The Great Buffalo Hunt (University of Nebraska Press, 1954)

- Isenberg, Andrew C. (1992). "Toward a Policy of Destruction: Buffaloes, Law, and the Market, 1803–1883". Great Plains Quarterly. 12: 227–41.

- Isenberg, Andrew C. The Destruction of the Buffalo: An Environmental History, 1750–1920 (Cambridge University press, 2000) online edition

- Koucky, Rudolph W. (1983). "The Buffalo Disaster of 1882". North Dakota History. 50 (1): 23–30. PMID 11620389.

- McHugh, Tom. The Time of the Buffalo (University of Nebraska Press, 1972).

- Meagher, Margaret Mary. The Bison of Yellowstone National Park. (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1973)

- Punke, Michael. Last Stand: George Bird Grinnell, the Battle to Save the Buffalo, and the Birth of the New West (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. xvi, 286 pp. ISBN 978-0-8032-2680-7

- Rister, Carl Coke (1929). "The Significance of the Destruction of the Buffalo in the Southwest". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 33: 34–49. JSTOR 30237207.

- Roe, Frank Gilbert. The North American Buffalo: A Critical Study of the Species in Its Wild State (University of Toronto Press, 1951).

- Shaw, James H. (1995). "How Many Bison Originally Populated Western Rangelands?". Rangelands. 17 (5): 148–150. JSTOR 4001099.

- Smits, David D. (1994). "The Frontier Army and the Destruction of the Buffalo, 1865–1883" (PDF). Western Historical Quarterly. 25 (3): 313–38. JSTOR 971110. and 26 (1995) 203-8.

- Zontek, Ken (1995). "Hunt, Capture, Raise, Increase: The People Who Saved the Bison". Great Plains Quarterly. 15: 133–49.