Scythe: Difference between revisions

→Mythology: removed a poorly written and redundant sentence. |

Two common pronunciations |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Distinguish|Sickle}} |

{{Distinguish|Sickle}} |

||

[[Image:Scythe against hedge.jpg|thumb|A traditional wooden scythe.]] |

[[Image:Scythe against hedge.jpg|thumb|A traditional wooden scythe.]] |

||

A '''scythe''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|s|aɪ|ð}})<ref name="OED">''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'', Oxford University Press, 1933: Scythe</ref> is an [[agriculture|agricultural]] [[hand tool]] for [[mowing]] [[grass]] or [[Harvest|reaping]] [[agriculture|crops]]. It was largely replaced by [[horse]]-drawn and then [[tractor]] machinery, but is still used in some areas of [[Europe]] and [[Asia]]. The [[Grim Reaper]] and the Greek Titan [[Cronus]] are often depicted carrying or wielding a scythe. |

A '''scythe''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|s|aɪ|ð}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|aɪ|θ}})<ref name="OED">''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'', Oxford University Press, 1933: Scythe</ref> is an [[agriculture|agricultural]] [[hand tool]] for [[mowing]] [[grass]] or [[Harvest|reaping]] [[agriculture|crops]]. It was largely replaced by [[horse]]-drawn and then [[tractor]] machinery, but is still used in some areas of [[Europe]] and [[Asia]]. The [[Grim Reaper]] and the Greek Titan [[Cronus]] are often depicted carrying or wielding a scythe. |

||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Revision as of 18:58, 26 May 2013

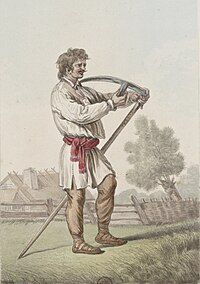

A scythe (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈsaɪð/ or /ˈsaɪθ/)[1] is an agricultural hand tool for mowing grass or reaping crops. It was largely replaced by horse-drawn and then tractor machinery, but is still used in some areas of Europe and Asia. The Grim Reaper and the Greek Titan Cronus are often depicted carrying or wielding a scythe.

Etymology

"Scythe" derives from Old English siðe.[1] In Middle English and after it was usually spelt sithe or sythe. However, in the 15th century some writers began to use the sc- spelling as they (wrongly) thought the word was related to the Latin scindere (meaning "to cut").[2] Nevertheless, the sithe spelling lingered and notably appears in Noah Webster's dictionaries.[3][4]

Structure

Template:Multicol 1. Toe

2. Chine

3. Beard

4. Heel

Template:Multicol-break 5. Tang

6. Ring

7. Snath or snaith

8. Grips

Template:Multicol-end

A scythe consists of a wooden shaft about 170 centimetres (67 in) long called a snaith, snath, snathe or sned (modern versions are sometimes made from metal or plastic). The snaith may be straight, or with an "S" curve, but the more sophisticated versions are curved in three dimensions, allowing the mower to stand more upright. The snaith has either one or two short handles at right angles to it – usually one near the upper end and always another roughly in the middle. A long, curved blade about 60 to 90 centimetres (24 to 35 in)) long is mounted at the lower end, perpendicular to the snaith. Scythes always have the blade projecting from the left side of the snaith when in use, with the edge towards the mower. In principle a left-handed scythe could be made, but it could not be used together with right-handed scythes in a team of mowers, as the left-handed mower would be mowing in the opposite direction.

A scythe blade is made by peening the leading edge of the blade. In some uses, such as for mowing grass, the blade-edge is made almost as thin as paper. After peening, the edge is finished and subsequently maintained by very frequent stropping or honing with a whetstone or rubber (fine-grained for grass, coarser for cereal crops), and peened again as necessary to recover the fineness of the edge.

The "American" scythe blade is not usually peened as part of sharpening, being made using a stamping process that produces a harder blade than other styles of scythe blade. The harder blade holds an edge longer and requires less frequent sharpening. Rather than being maintained through peening, the edge of the American pattern of blade is traditionally reshaped after heavy use by grinding on a large diameter grindstone.

Use

Using a scythe is called mowing, or often scything, to distinguish it from mowing with more complex machinery. Mowing is done by holding the top handle in the left hand and the central one in the right, with the arms straight, the blade parallel to the ground and very close to it, and the body twisted to the right. The body is then twisted steadily to the left, moving the scythe blade along its length in a long arc from right to left, ending in front of the mower, thus depositing the cut grass to the left. Mowing proceeds with a steady rhythm, stopping at frequent intervals to sharpen the blade. The correct technique has a slicing action on the grass, cutting a narrow strip with each stroke – a common beginner's error is to chop or hack at the grass, with the blade length at right angles to it, thus trying to cut too wide a strip of grass at once. This is much harder work, and is ineffective. Cutting too close to the ground can contaminate the blade with soil, rapidly blunting it. Much of the skill is in keeping the blade close to the ground and the cuts even.

Mowing is normally done cutting out of the uncut grass, the mower moving along the mowing-edge with the uncut grass to their right. The cut grass is laid in a neat row to the left, on the previously mown land. Each strip of ground mown by a scythe is called a swathe (pronounced /ˈsweɪð/: rhymes with "bathe") or swath (/ˈswɒθ/: rhymes with "Goth"). Mowing may be done by a team of mowers, usually starting at the edges of a meadow then proceeding clockwise and finishing in the middle. Mowing grass is easier when it is damp, and so hay-making traditionally began at dawn and often stopped early, the heat of the day being spent raking and carting the hay cut on previous days.

Mowing with a scythe is a skilled task, performed with relative ease by experienced mowers, but often poorly and with very great effort by beginners. Long-bladed traditional scythes with double-curved wooden snaiths are harder to use at first, but once mastered are more effective and comfortable for longer periods. Shorter-bladed or hack-scythes are easier for beginners. A skilled mower using a traditional long-bladed scythe can even cut very short grass, and this is how lawns were maintained until the invention of the lawnmower.

In addition to mowing grass and reaping crops, a scythe can also be used for mowing reed or sedge, remaining effective even with the blade under water.

The scythe and pitchfork have frequently been used as a weapon by those who couldn't afford or didn't have access to more expensive weapons such as swords, or later, guns.[citation needed] As a result, scythes and pitchforks are stereotypically carried by angry mobs or gangs of enraged peasants.[citation needed]

History

According to the Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities of Sir William Smith, the scythe, known in Latin as the falx foenaria (as opposed to the sickle, the falx messoria), was used by the ancient Romans; for illustration, Smith shows an image of Saturn holding a scythe, from an ancient Italian cameo.

According to Jack Herer and "Flesh of The Gods" (Emboden, W.A., Jr., Praeger Press, NY, 1974.); the ancient Scythians grew hemp and harvested it with a hand reaper that we still call a scythe.

The scythe was invented in about 500 BC and appeared in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries. Initially used mostly for mowing grass, it replaced the sickle as the tool for reaping crops by the 16th century, the scythe allowing the reaper to stand rather than stoop. In about 1800 the addition of light wooden fingers above a scythe blade produced a form of scythe called the cradle which soon replaced the simple scythe for reaping grain and mowing other tall vegetation such as reeds. In the developed world, all of these have now largely been replaced by motorized lawnmowers and combine harvesters.

The Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet in Sheffield, England is a museum of a scythe-making works that was in operation from the end of the 18th century until the 1930s.[5] This was part of the former scythe-making district of north Derbyshire, which extended into Eckington.[6] Other English scythe-making districts include that around Belbroughton.[7]

Mowing with a scythe remained common for many years even after most mowing became mechanized, because a side-mounted finger-bar mower (whether horse or tractor drawn) cannot mow in front of itself. Scythes would therefore be used to open up a meadow – to mow the first swathes, thus letting the mechanical mower in to complete the mowing.

Scythes in national cultures

The scythe is still an indispensable tool for farmers in developing countries and in mountainous terrain.

In Romania, for example, in the highland landscape of the Apuseni mountains,[8] scything is a very important annual activity, taking about 2–3 weeks to complete for a regular house[needs citation]. As scything is a tiring physical activity and is relatively difficult to learn, farmers help each other by forming teams. After each day's harvest, the farmers often celebrate by having a small feast where they dance, drink and eat, while being careful to keep in shape for the next day's hard work. In other parts of the Balkans, such as in Serbian towns, scything competitions are held where the winner takes away a small silver scythe.[9] In small Serbian towns, scything is treasured as part of the local folklore, and the winners of friendly competitions are rewarded richly[10] with food and drink, which they share with their competitors.

Among Basques scythe-mowing competitions are still a popular traditional sport, called segalaritza (from sega: scythe). Each contender competes to cut a defined section of grown grass before his rival does the same.

There is an international scything competition held at Goricko[11] where people from Austria, Hungary, Serbia and Romania, or as far away as Asia appear to showcase their culturally unique method of reaping crops.[12] In 2009, a Japanese gentleman showcased a wooden reaping tool with a metal edge, which he used to show how rice was cut. He was impressed with the speed of the local reapers, but said such a large scythe would never work in Japan.

The Norwegian municipality of Hornindal has three scythe blades in its coat-of-arms.

Scythes are beginning a comeback in American suburbs, since they "don't use gas, don't get hot, don't make noise, do make for exercise, and do cut grass."[13]

Mythology

The scythe also plays an important traditional role, often appearing as weapons in the hands of mythical beings such as Cronus, and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, specifically, Grim Reaper (Death). This stems mainly from the Christian Biblical belief of death as a "harvester of souls."[disputed – discuss]

War scythe

A war scythe is a regular scythe that has been adapted for combat use by re-attaching the blade parallel to the haft, rather than perpendicular to it, so that it looks like a bill. After the German Peasants' War during 1524–1525, a fencing book edited by Paulus Hector Mair described in 1542 techniques how to fence using a scythe.[14] War scythes were widely used by Polish and Lithuanian peasants during revolts in the 18th and 19th centuries.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 1933: Scythe

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary: scythe

- ^ "Browse 1828 => Word SITHE :: Search the 1828 Noah Webster's Dictionary of the English Language". 1828.mshaffer.com. 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ "Browse 1913 => Word SITHE :: Search the 1913 Noah Webster's Dictionary of the English Language". 1913.mshaffer.com. 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Sheffield Industrial Museums Trust. Simt.co.uk (2010-10-03). Retrieved on 2011-03-09.

- ^ K. M. Battye, 'Sickle-makers and other metalworkers in Eckington 1534–1750: a study of metal workers tools, raw materials and made goods, using probate wills and inventories' Tools and Trades 12 (2000), 26–38.

- ^ P. W. King, 'The north Worcestershire Scythe Industry' Historical Metallurgy 41(2), 124–47.

- ^ Reif, Albert; Ruşdea, Evelyn; Păcurar, Florin; Rotar, Ioan; Brinkmann, Katja; Auch, Eckhard; Goia, Augustin; Bühler, Josef (2008). "A Traditional Cultural Landscape in Transformation". Mountain Research and Development. 28: 18. doi:10.1659/mrd.0806.

- ^ Events in Serbia. Hay making on Rajac. Accommodation in Sumadija. Guaranted Tours. Visitserbia.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-09.

- ^ Serbian Scything Competition on Mt. Plavinac photo | stock photos Profimedia #0071934552. Profimedia.rs (2010-06-13). Retrieved on 2011-03-09.

- ^ Krajinski park Goričko. Park-goricko.org (2010-05-21). Retrieved on 2011-03-09.

- ^ Blog Archives. The One Scythe Revolution (2010-02-28). Retrieved on 2011-03-09.

- ^ Newman, Barry (June 29, 2012). "Who Needs a WeedWacker When You Can Use a Scythe? Grim Reaper Jokes Aside, Suburbanites Take Swing at Ancient Mower". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Mair, Paul Hector (c.1542). "Sichelfechten (Sickle Fencing)". De arte athletica I (in German/Latin). Augsburg. pp. 204r–208r.

Duæ incisiones supernæ falcis foe

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

External links

- Scythe Network, a site dedicated to modern usage, with links to numerous equipment suppliers in North America.

- http://www.autonopedia.org.uk/appropriate_technology/Tools/Tools_and_How_to_Use_Them/Adze_Hooks_and_Sythe.html.