The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Difference between revisions

→Plot: I de-clumsified a few awkward passages. |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

The film used stylized sets, with abstract, jagged buildings painted on canvas backdrops and flats. To add to this strange style, the actors used an unrealistic technique that exhibited "jerky" and dance-like movements. |

The film used stylized sets, with abstract, jagged buildings painted on canvas backdrops and flats. To add to this strange style, the actors used an unrealistic technique that exhibited "jerky" and dance-like movements. |

||

This movie is cited as having introduced '' |

This movie is cited as having introduced the'' [[Plot twist|twist ending]]'' in cinema. |

||

== Plot == |

== Plot == |

||

Revision as of 19:52, 4 August 2013

| The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Robert Wiene |

| Written by | Hans Janowitz Carl Mayer |

| Produced by | Rudolf Meinert Erich Pommer |

| Starring | Werner Krauss Conrad Veidt Friedrich Fehér Lil Dagover Hans Twardowski |

| Cinematography | Willy Hameister |

| Music by | Giuseppe Becce |

| Distributed by | Decla-Bioscop (Germany) Goldwyn Distributing Company (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 71 minutes |

| Country | Weimar Republic |

| Languages | Silent film German intertitles |

| Budget | DEM 20,000 (estimated) |

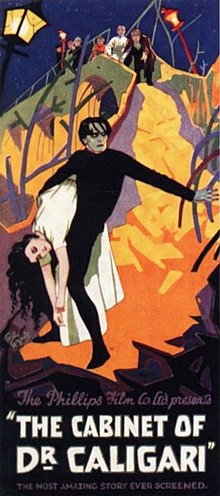

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (German: Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) is a 1920 German silent horror film directed by Robert Wiene from a screenplay by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer. It is one of the most influential of German Expressionist films and is often considered being one of the greatest horror movies of the silent era in film.

The film used stylized sets, with abstract, jagged buildings painted on canvas backdrops and flats. To add to this strange style, the actors used an unrealistic technique that exhibited "jerky" and dance-like movements.

This movie is cited as having introduced the twist ending in cinema.

Plot

The main narrative is introduced using a frame story in which most of the plot is presented as a flashback, as told by the protagonist, Francis (one of the earliest examples of a frame story in film).

Francis (Friedrich Fehér) and an elderly companion are sharing stories when a seemingly distracted woman, Jane (Lil Dagover), passes by. Francis calls her his betrothed and narrates an interesting tale that he and Jane share.

Francis begins his story with himself and his friend Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski), who are both good-naturedly competing to be married to the lovely Jane. The two friends visit a carnival in their German mountain village of Holstenwall. They encounter the captivating Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) and a near-silent somnambulist, Cesare (Conrad Veidt), whom the doctor keeps asleep in a coffin-like cabinet, controls hypnotically, and is displaying as an attraction. Caligari hawks that Cesare's continuous sleeping state allows him to know the answer to any question about the future. When Alan asks Cesare how long he shall live, then Cesare bluntly replies that Alan shall die at dawn — a prophecy which is fulfilled. Alan's violent death at the hands of some shadowy figure becomes the most recent in a series of mysterious murders in Holstenwall.

Francis and Jane (to whom he is now officially engaged) investigate Caligari and Cesare. Doctor Caligari finds out and orders Cesare to murder Jane. He very nearly succeeds, suggesting to Francis that Cesare and his master Caligari are indeed responsible for the recent homicides. Thanks to Jane's ethereal beauty, however, Cesare finds himself unable to stab her to death and settles for kidnapping her instead. In hot pursuit by the townsfolk, Cesare finally releases Jane as he falls over from exhaustion and dies.

In the meantime, Francis goes to Holstenwall's local insane asylum to ask if there has ever been a patient there by the name of Caligari, only to be shocked to discover that Caligari is the asylum's director. With the help of some of Caligari's oblivious colleagues at the asylum, Francis discovers through old records that the man known as "Dr. Caligari" is obsessed with the story of a mythical monk called Caligari, who in 1703 visited towns in northern Italy and, in a similar manner, used a somnambulist under his control to kill people. Dr. Caligari, insanely driven to see if such a situation could actually occur, deemed himself "Caligari" and has since successfully carried out his string of proxy murders. Francis and the asylum's other doctors send the authorities to Caligari's office. Caligari reveals his lunacy only when he understands that his beloved slave, Cesare, has died; Caligari then becomes an inmate in his own asylum.

The narrative returns to the present moment, with Francis concluding his tale. A twist ending reveals that Francis' flashback, however, is actually his fantasy. He and Jane and Cesare are all in fact inmates of the insane asylum. The man whom he claims to be "Caligari" is actually his asylum doctor. Francis goes berserk and is put in a straightjacket and consigned to the very same cell as was the imaginary Dr. Caligari. His doctor says that since the delusional source of his patient's dementia has been revealed he shall now be able to cure poor Francis.

Cast

- Werner Krauss as Dr. Caligari

- Conrad Veidt as Cesare

- Friedrich Fehér as Francis

- Lil Dagover as Jane Olsen

- Hans Heinrich von Twardowski as Alan

- Rudolf Lettinger as Dr. Olsen

Uncredited

- Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Criminal

- Hans Lanser-Rudolf as Old man

- Henri Peters-Arnolds as Young doctor

- Ludwig Rex as Murderer

- Elsa Wagner as Landlady

Development

Writers Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer first met in Berlin soon after World War I. The two men considered the new film medium as a new type of artistic expression – visual storytelling that necessitated collaboration between writers and painters, cameramen, actors, directors. They felt that film was the ideal medium through which to both call attention to the emerging pacifism in postwar Germany and exhibit radical anti-bourgeois art.[1]

Although neither had associations with any Berlin film company, they decided to develop a plot. As both were enthusiastic about Paul Wegener's works, they chose to write a horror film. The duo drew from past experiences. Janowitz had disturbing memories of a night during 1913, in Hamburg. After leaving a fair he had walked into a park bordering the Holstenwall and glimpsed a stranger as he disappeared into the shadows after having mysteriously emerged from the bushes. The next morning, a young woman's ravaged body was found. Mayer was still angered about his sessions during the war with an autocratic, highly ranked, military psychiatrist.[1]

At night, Janowitz and Mayer often went to a nearby fair. One evening, they saw a sideshow "Man and Machine", in which a man did feats of strength and predicted the future while supposedly in a hypnotic trance. Inspired by this, Janowitz and Mayer devised their story that night and wrote it in the following six weeks. The name "Caligari" came from a book Mayer had read, in which an officer named Caligari was mentioned.[1]

When the duo approached producer Erich Pommer about the story, Pommer tried to have them thrown out of his small Decla-Bioscop studio. But when they insisted on telling him their film story, Pommer was so impressed that he bought it on the spot, and agreed to have the film produced in expressionistic style, partly as a concession to his studio only having a limited quota of power and light.[1]

Production

Pommer put Caligari in the hands of designer Hermann Warm and painters Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig, whom he had met as a soldier while painting sets for a German military theater. When Pommer began to have second thoughts about how the film should be designed, they had to convince him that it made sense to paint lights and shadows directly on set walls, floors, background canvases and to place flat sets behind the actors.[1]

Pommer first approached Fritz Lang to direct this film, but Lang was committed to work on Die Spinnen (The Spiders),[1] so Pommer gave directorial duties to Robert Wiene. Wiene filmed a test scene to prove Warm, Reimann, and Röhrig's theories, and it was so impressive that Pommer gave his artists free rein. Janowitz, Mayer, and Wiene would later use the same artistic methods on another production, Genuine, which was less successful commercially and critically.[1]

The producers, who wanted a less macabre ending, imposed upon the director the idea that everything turns out to be Francis's delusion. In so doing, they produced the first cinematographic representation of altered mental states.[2]

The original story made it clear that Caligari and Cesare were real and were responsible for a number of deaths.[3]

Filming took place during December 1919 and January 1920. The film premiered at the Marmorhaus in Berlin on February 26, 1920.[4]

Responses

Critics worldwide have praised the film for its Expressionist style, complete with wild, distorted set design. Caligari has been cited as an influence on Film noir, one of the earliest horror films, and a model for directors for many decades.

Upton Sinclair wrote They Call Me Carpenter in 1922. This book began with a crowd of people trying to keep Americans from seeing "Caligari" because this story of a "madman" didn't serve the purpose of art, morality. His question was whether art was to serve morality or if art exists for "art's sake."[5]

Siegfried Kracauer's From Caligari to Hitler (1947) postulates that the film can be considered as an allegory for German social attitudes in the period following World War I. He argues that the character of Caligari represents a tyrannical figure, to whom the only alternative is social chaos (represented by the fairground).[6]

However, in Weimar Cinema and After, Thomas Elsaesser describes the legacy of Kracauer's work as a "historical imaginary".[7] Elsaesser argues that Kracauer had not studied enough films to make his thesis about the social mindset of Germany legitimate and that the discovery and publication of the original screenplay of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari undermines his argument about the revolutionary intent of its writers. Elsaesser's alternative thesis is that the filmmakers adopted an Expressionist style as a method of product differentiation, establishing a distinct national product against the increasing importation of American films. Dietrich Scheunemann, somewhat in defense of Kracauer, noted that he didn't have "the full range of materials at (his) disposal". However, that fact "has clearly and adversely affected the discussion of the film", referring to the fact that the script of Caligari wasn't rediscovered until 1977 and that Kracauer hadn't seen the film for around 20 years when he wrote the work.[8]

Sequel

There was a sequel of sorts in the 1980s with the film Dr. Caligari. It dealt with the granddaughter of the original Dr. Caligari and her illegal experiments on her patients in an asylum. Its tone, look, and feel held similarities to the original film, but was more influenced by the works of David Lynch and David Cronenberg than of the German Expressionists. The sequel was surprisingly well-received.

Adaptations and musical works inspired by the film

In 1962, a British version of the film was made called The Cabinet of Caligari with a script by Robert Bloch, the author of Psycho.

In 1991, the film was loosely remade as The Cabinet of Dr. Ramirez by director and writer Peter Sellars. The production included significant development during filming, leading the primary actors to also receive writing credits (Mikhail Baryshnikov, who played "Cesar"; Joan Cusack, who played "Cathy"; Peter Gallagher, who played "Matt", and Ron Vawter, who played "Dr. Ramirez"). This remake was an experimental film that was screened only at the 1992 Sundance Film Festival and never theatrically released.[9]

The film was adapted into an opera in 1997 by composer John Moran. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari premiered at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a production by Robert McGrath.[10] Numerous musicians have composed new musical scores to accompany the film. The Club Foot Orchestra premiered the score penned by ensemble founder and artistic director Richard Marriott in 1987.[11] In 2000, the Israeli Electronica group TaaPet made several live performances of their soundtrack for the film around Israel.[12]

In 1981, Bill Nelson was asked by the Yorkshire Actors Company to create a soundtrack for a stage adaptation of the movie. That music was later recorded for his 1982 album Das Kabinet (The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari).[13]

There is strong influence of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari on the concept of the 2009 fantasy film The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus, by Terry Gilliam as well as on the book Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane, on which the eponymous movie by Martin Scorsese is based.[14]

Comic books

Jean-Marc Lofficier wrote Superman's Metropolis, a trilogy of graphic novels for DC Comics illustrated by Ted McKeever, the second of which was entitled Batman: Nosferatu, most of the plot derived from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Caligari himself appears as a member of Die Zwielichthelden (The Twilight Heroes), a German mercenary group in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier by Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill. Also, in The Sandman issue "Calliope" written by Neil Gaiman and pencilled by Kelley Jones, a character, Richard Madoc, writes a book "The Cabaret of Dr. Caligari", an obvious pseudonym.

Musical references

The name 'Caligari' has been used extensively in popular music. Pere Ubu has a song entitled "Caligari's Mirror". Goth rock group Bauhaus used a still of Cesare from the film on early t-shirts for their popular single "Bela Lugosi's Dead". The band Abney Park has a cut "The Secret Life of Dr. Calgari" on their album Lost Horizons (released 2008). There is also a Japanese rock band that has called itself after the film, Cali Gari.

The 1998 music video for Rob Zombie's single "Living Dead Girl" restaged several scenes from the film, with Zombie in the role of Caligari beckoning to the fair attendees. In addition to artificially imitating the poor image quality of aged film, the video also made use of the expressionistic sepia, aqua, and violet tinting used in Caligari. The film also inspired imagery in the video for "Forsaken" (2002), from the soundtrack for the film Queen of the Damned.

Hard rock group Rainbow used the film as inspiration for the music video to "Can't Let You Go", a single from their 1983 album Bent Out Of Shape, vocalist Joe Lynn Turner being made up as Cesare. The director was Dominic Orlando. The video for Coldplay's "Cemeteries of London" included clips from the film. The video for the song "Otherside" by the Red Hot Chili Peppers off the album Californication, briefly used the film as a reference to its visuals.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Peary, Danny (1988). Cult Movies 3. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. pp. 48–51. ISBN 0-671-64810-1.

- ^ Giannini, A. J. (1999).

- ^ White, Rob (2003). British Film Institute film classics. Vol. 1. Routledge. pp. 2–4. ISBN 1-57958-328-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Robinson, David (1997). Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari. British Film Institute. p. 47.

- ^ They Call me Carpenter Gutenberg -- They Call me Carpenter Librivox

- ^ Kracauer, Siegfried (2004 edition; 1947, original English translation). From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film. Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Elsaesser, Thomas (2000). Weimar Cinema and After: Germany's Historical Imaginary. Routledge.

- ^ Scheunemann, Dietrich (2003). "The Double, the Decor, the Framing Device: Once More on Robert Weine's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari". In Scheunemann, Dietrich (ed.). Expressionist Films: New Perspectives. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 1-57113-068-3.

- ^ "The Cabinet of Dr. Ramirez | Archives | Sundance Institute". History.sundance.org. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari multimedia theatre piece.

- ^ "The Cabinet of Dr Caligari". Club Foot Orchestra. 1987-10-17. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "TaaPet.com". TaaPet.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Bill Nelson Biography. Hal Leonard. 1997. p. 87.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|book=ignored (help) - ^ He was shocked that I'd never seen the "Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," which he was sure was an influence http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704820904575055330609042848.html

Further reading

- Budd, Mike (editor) (1990) The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey, ISBN 0-8135-1570-X

- Eisner, Lotte H. (1969) The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (translated from the French by Roger Greaves) University of California Press, Berkeley, California, OCLC 651180268 ISBN 978-0-520-25790-0

- Hantke, Steffen (editor) (2006) Caligari's Heirs: The German Cinema of Fear after 1945 Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, ISBN 0-8108-5878-9

- Robinson, David (1997) Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari British Film Institute Publishing, London, ISBN 0-85170-645-2

- Wiene, Robert; Mayer, Carl and Janowitz, Hans (1984) The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: A Film (revised edition, translated from German by R. V. Adkinson) Lorrimer, London, ISBN 0-85647-084-8

References

- Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell. Film History, An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages, 2010. 92,93. Print. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3

External links

- Cabinet of Dr. Caligari at YouTube (full-length film)[dead link]

- From Caligari to Hitler - A philosophical analysis of the Cabinet of Dr Caligari, by Siegfried Kracauer.

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari at IMDb

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari at AllMovie

- An Article on The Cabinet of Dr.Caligari published at BrokenProjector.com

- Transcription on Aellea Classic Movie Scripts.

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari - summary of the plot.

- Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari (1920) - review

- Paquin, Alexandre (2001-05-15). "Caligari: A German Silent Masterpiece". Archived from the original on 2006-10-20. - review