Winterreise: Difference between revisions

Double sharp (talk | contribs) →Opinions of Schubert's intentions: uncited. while he may have been in good health, he did have syphilis at this point, and it killed him. (enough of the typhoid fever protect-thy-reputation) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

* [[Jens Josef]] created in 2001 a version for tenor and string quartet. It was recorded by Christian Elsner and the [[Henschel Quartet]] in 2002,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=53291 |title=Schubert: Winterreise / Christian Elsner, Henschel Quartet |year=2002 |accessdate=30 November 2010 |publisher=arkivmusic.com }}</ref> and performed in 2004 by [[Peter Schreier]] and the Dresdner Streichquartett.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mhalberstadt.net/rec_archief04.htm#4tet |title=Bekannte Tour durch eine neue Klangwelt |language=German |date=21 June 2004 |accessdate=30 November 2010 |publisher=Sächsische Zeitung }}</ref> |

* [[Jens Josef]] created in 2001 a version for tenor and string quartet. It was recorded by Christian Elsner and the [[Henschel Quartet]] in 2002,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=53291 |title=Schubert: Winterreise / Christian Elsner, Henschel Quartet |year=2002 |accessdate=30 November 2010 |publisher=arkivmusic.com }}</ref> and performed in 2004 by [[Peter Schreier]] and the Dresdner Streichquartett.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mhalberstadt.net/rec_archief04.htm#4tet |title=Bekannte Tour durch eine neue Klangwelt |language=German |date=21 June 2004 |accessdate=30 November 2010 |publisher=Sächsische Zeitung }}</ref> |

||

* [[John Neumeier]] made a ballet to ''Winterreise'' on his [[Hamburg Ballet]] company in December 2001.<ref>[http://www.hamburgballett.de/e/neumeier.htm biography of John Neumeier on Hamburg Ballet website]</ref> |

* [[John Neumeier]] made a ballet to ''Winterreise'' on his [[Hamburg Ballet]] company in December 2001.<ref>[http://www.hamburgballett.de/e/neumeier.htm biography of John Neumeier on Hamburg Ballet website]</ref> |

||

* Oboist Normand Forget made a chamber version for accordion and |

* Oboist Normand Forget made a unique chamber version for accordion and wind quintet including bass clarinet, [[oboe d'amore]] and baroque horn, recorded in September 2007 by tenor [[Christoph Prégardien]], accordionist Joseph Petric, and the Montréal ensemble Pentaèdre.<ref>Pentaèdre (Danièle Bourget, Martin Charpentier, Normand Forget, Louis-Philippe Marsolais, Mathieu Lussier). ATMA ACD2 2546 [http://www.atmaclassique.com] This version was performed by at the Hohenems Schubertiade(2009) and in the Berlin Philharmonik Chambermusic series in 2013 with the Berlin Philharmonic Woodwind Quintet.</ref> |

||

* The deaf actor Horst Dittrich translated the cycle of poems into [[Austrian Sign Language]] in 2007 and presented it on stage in a production of [[ARBOS – Company for Music and Theatre]] directed by [[Herbert Gantschacher]], with Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano), in 2008 in Vienna and Salzburg and in 2009 in [[Villach]] (Austria).<ref>[http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x5oj6x_franz-schubert-winter-journey-illus_music] "Illusion" by Franz Schubert and Wilhelm Müller on stage by Horst Dittrich (Austrian Sign Language), Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano)</ref> |

* The deaf actor Horst Dittrich translated the cycle of poems into [[Austrian Sign Language]] in 2007 and presented it on stage in a production of [[ARBOS – Company for Music and Theatre]] directed by [[Herbert Gantschacher]], with Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano), in 2008 in Vienna and Salzburg and in 2009 in [[Villach]] (Austria).<ref>[http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x5oj6x_franz-schubert-winter-journey-illus_music] "Illusion" by Franz Schubert and Wilhelm Müller on stage by Horst Dittrich (Austrian Sign Language), Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano)</ref> |

||

*Rick Burkhardt, Alec Duffy and Dave Malloy created an [[Obie Award|Obie award]]-winning theatrical adaptation of the cycle, ''Three Pianos'', which played at the [[Ontological-Hysteric Theater]] and [[New York Theater Workshop]] in 2010 and the [[American Repertory Theater]] in 2011.<ref>[http://threepianos.com/]</ref> |

*Rick Burkhardt, Alec Duffy and Dave Malloy created an [[Obie Award|Obie award]]-winning theatrical adaptation of the cycle, ''Three Pianos'', which played at the [[Ontological-Hysteric Theater]] and [[New York Theater Workshop]] in 2010 and the [[American Repertory Theater]] in 2011.<ref>[http://threepianos.com/]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:56, 28 October 2013

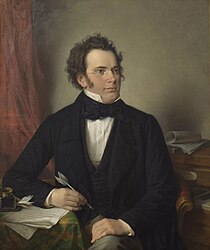

Winterreise (Winter Journey) is a song cycle for voice and piano by Franz Schubert (D. 911, published as Op. 89 in 1828), a setting of 24 poems by Wilhelm Müller. It is the second of Schubert's two great song cycles on Müller's poems, the earlier being Die schöne Müllerin (D. 795, Op. 25, 1823). Both were originally written for tenor voice but are frequently transposed to suit other vocal ranges - the precedent being established by Schubert himself. These two works have posed interpretative demands on listeners and performers due to their scale and structural coherence. Although Ludwig van Beethoven's cycle An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved) had been published earlier, in 1816, Schubert's two cycles hold the foremost place in the history of the genre.[citation needed]

Authorship and composition

Winterreise was composed in two parts, each containing twelve songs, the first part in February 1827 and the second in October 1827.[1] The two parts were also published separately, by Tobias Haslinger, the first on 14 January 1828, and the second (the proofs of which Schubert was still correcting days before his death on 19 November) on 30 December 1828.[2] Müller, a poet, soldier, and Imperial Librarian at Dessau in Prussia (present-day east-central Germany), died in 1827 aged 33, and probably never heard the first setting of his poems in Die schöne Müllerin (1823), let alone Winterreise. Die schöne Müllerin had become central to the performing repertoire and partnership of Schubert with his friend, the baritone singer Johann Michael Vogl, who introduced Schubert and his songs into many musical households great and small in their tours through Austria during the mid-1820s.

Vogl, a literary and philosophical man accomplished in the classics and the English language, came to regard Schubert's songs as 'truly divine inspirations, the utterance of a musical clairvoyance.' Schubert found the first twelve poems under the title Wanderlieder von Wilhelm Müller. Die Winterreise. In 12 Liedern in an almanack (Urania. Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1823) published in Leipzig in 1823.[3] It was after he had set these, in February 1827, that he discovered the full series of poems in Müller's book of 1824 entitled Poems from the posthumous papers of a travelling horn-player, dedicated to the composer Carl Maria von Weber (godfather of Müller's son F. Max Müller), 'as a pledge of his friendship and admiration'. Weber had died in 1826. On 4 March 1827, Schubert invited a group of friends to his lodgings intending to sing the first group of songs, but he was out when they arrived, and the event was postponed until later in the year, when the full performance was given.[4]

Between the 1823 and 1824 editions Müller varied the texts slightly, but also (with the addition of the further 12 poems) altered the order in which they were presented. Owing to the two stages of composition, Schubert's order in the song-cycle preserves the integrity of the cycle of the first twelve poems published and appends the twelve new poems as a Fortsetzung (Continuation), following Müller's order (if one excludes the poems already set) with the one exception of switching "Die Nebensonnen" and "Mut!".[5] In the complete book edition Müller's final running-order was as follows: Gute Nacht; Die Wetterfahne; Gefror'ne Thränen; Erstarrung; Der Lindenbaum; Die Post; Wasserfluth; Auf dem Flusse; Rückblick; Der greise Kopf; Die Krähe; Letzte Hoffnung; Im Dorfe; Der stürmische Morgen ; Täuschung; Der Wegweiser; Das Wirthshaus; [Das] Irrlicht; Rast; Die Nebensonnen; Frühlingstraum; Einsamkeit; Mut!; Der Leiermann.[6] Thus Schubert's numbers would run 1-5, 13, 6-8, 14-21, 9-10, 23, 11-12, 22, 24, a sequence occasionally attempted by Hans Joachim Moser and Günther Baum.

Schubert's original group of settings therefore closed with the dramatic cadence of "Irrlicht", "Rast", "Frühlingstraum" and "Einsamkeit", and his second sequence begins with "Die Post". Dramatically the first half is the sequence from the leaving of the beloved's house, and the second half the torments of reawakening hope and the path to resignation.

In Winterreise Schubert raises the importance of the pianist to a role equal to that of the singer. In particular the piano's rhythms constantly express the moods of the poet, like the distinctive rhythm of "Auf dem Flusse", the restless syncopated figures in "Rückblick", the dramatic tremolos in "Einsamkeit", the glimmering clusters of notes in "Irrlicht", or the sharp accents in "Der stürmische Morgen". The piano supplies rich effects in the Nature imagery of the poems, the voices of the elements, the creatures and active objects, the rushing storm, the crying wind, the water under the ice, birds singing, ravens croaking, dogs baying, the rusty weathervane grating, the posthorn calling, and the drone and repeated melody of the hurdy-gurdy.[7]

Opinions of Schubert's intentions

What might have forced the composer to confront and create the somber "Winterreise"? A possible explanation is documented in a book by Elizabeth Norman McKay, Schubert: The Piano and Dark Keys: "Towards the end of 1822 ... Schubert was very sick, having contracted the syphilis that inevitably was to affect the remainder of his life: his physical and mental health, and the music he was to compose." As detailed below, he worked on “Die Winterreise” as he was dying of syphilis.[8]

In addition to his friend Franz von Schober, Schubert's friends who often attended his Schubertiaden or musical sessions included Eduard von Bauernfeld, Joseph von Spaun, and the poet Johann Mayrhofer. Both Spaun and Mayrhofer describe the period of the composition of Winterreise as one in which Schubert was in a deeply melancholic frame of mind, as Mayrhofer puts it, because 'life had lost its rosiness and winter was upon him.' Spaun tells that Schubert was gloomy and depressed, and when asked the reason replied,

' "Come to Schober's today and I will play you a cycle of terrifying songs; they have affected me more than has ever been the case with any other songs." He then, with a voice full of feeling, sang the entire Winterreise for us. We were altogether dumbfounded by the sombre mood of these songs, and Schober said that one song only, "Der Lindenbaum", had pleased him. Thereupon Schubert leaped up and replied: "These songs please me more than all the rest, and in time they will please you as well." '.[9]

It is argued that in the gloomy nature of the Winterreise, compared with Die schöne Müllerin, there is

a change of season, December for May, and a deeper core of pain, the difference between the heartbreak of a youth and a man. There is no need to seek in external vicissitudes an explanation of the pathos of the Winterreise music when the composer was this Schubert who, as a boy of seventeen, had the imagination to fix Gretchen's cry in music once for all, and had so quivered year by year in response to every appeal, to Mignon's and the Harper's grief, to Mayrhofer's nostalgia. It is not surprising to hear of Schubert's haggard look in the Winterreise period; but not depression, rather a kind of sacred exhilaration... we see him practically gasping with fearful joy over his tragic Winterreise - at his luck in the subject, at the beauty of the chance which brought him his collaborator back, at the countless fresh images provoked by his poetry of fire and snow, of torrent and ice, of scalding and frozen tears. The composer of the Winterreise may have gone hungry to bed, but he was a happy artist."[10]

Schubert's last task in life was the correction of the proofs for part 2 of Winterreise, and his thoughts while correcting those of the last song, "Der Leiermann", when his last illness was only too evident, can only be imagined. However, he had heard the whole cycle performed by Vogl (which received a much more enthusiastic reception),[11] though he did not live to see the final publication, nor the opinion of the Wiener Theaterzeitung:

Müller is naive, sentimental, and sets against outward nature a parallel of some passionate soul-state which takes its colour and significance from the former. Schubert's music is as naive as the poet's expressions; the emotions contained in the poems are as deeply reflected in his own feelings, and these are so brought out in sound that no-one can sing or hear them without being touched to the heart.[12]

Elena Gerhardt said of the Winterreise, "You have to be haunted by this cycle to be able to sing it."[11]

Nature of the work

In his introduction to the Peters Edition (with the critical revisions of Max Friedländer), Professor Max Müller, son of the poet Wilhelm Müller, remarks that Schubert's two song-cycles have a dramatic effect not unlike that of a full-scale tragic opera, particularly when performed by great singers such as Jenny Lind (Die schöne Müllerin) or Julius Stockhausen (Winterreise). Like Die schöne Müllerin, Schubert's Winterreise is not merely a collection of songs upon a single theme (lost or unrequited love) but is in effect one single dramatic monologue, lasting over an hour in performance. Although some individual songs are sometimes included separately in recitals (e.g. "Gute Nacht", "Der Lindenbaum" and "Der Leiermann"), it is a work which is usually presented in its entirety. The intensity and the emotional inflexions of the poetry are carefully built up to express the sorrows of the lover, and are developed to an almost pathological degree from the first to the last note.

The songs represent the voice of the poet as the lover, and form a distinct narrative and dramatic sequence, though not in so pronounced a way as in Die schöne Müllerin. In the course of the cycle the poet, whose beloved now fancies someone else, leaves his beloved's house secretly at night, quits the town and follows the river and the steep ways to a village. Having longed for death, he is at last reconciled to his loneliness. The cold, darkness, and barren winter landscape mirror the feelings in his heart, and he encounters various people and things along the way which form the subject of the successive songs during his lonely journey. It is in fact an allegorical journey of the heart.[citation needed]

The two Schubert cycles (primarily for male voice), of which Winterreise is the more mature, are absolute fundamentals of the German Lied, and have strongly influenced not only the style but also the vocal method and technique in German classical music as a whole. The resources of intellect and interpretative power required to deliver them, in the chamber or concert hall, challenges the greatest singers.[citation needed]

Synopsis

Early in the song cycle the wanderer sings about his lost beloved. As the work continues, he sings of abject loneliness, longing for death, and glimpses of delusional hope.

1. Gute Nacht (Good Night)

- By moonlight, in winter, the poet leaves the house as he came to it, a stranger. The daughter has allowed their love to grow, and the mother has encouraged the pair to think of marriage: but the daughter's love has wandered to some new sweetheart. So he quietly and secretly steals away while they are sleeping, writing 'Good night' on her door, and leaving the path of his footsteps in the snow.

2. Die Wetterfahne (The Weather-vane)

- As he goes he notices the winds blowing the weather-vane around on the house, and they blow him away from there as well. If he had taken notice of that fickle sign when he first came, he would not have expected to find a constant woman within. Indoors, their hearts beat like the vane, but not so loud - what do they care for his suffering, when their daughter will be a wealthy bride?.

3. Gefror'ne Tränen (Frozen Tears)

- Frozen tears fall from his cheeks as he walks away, but the breast from which they arise is so burning hot with feelings that they should melt the winter ice completely.

4. Erstarrung (Numbness)

- He looks in vain for her footprints in the snow, where they formerly walked together arm in arm among the flowers and green grass. He wants to kiss the ground and weep on it, until he can dissolve the ice and see where they trod. But the flowers are all dead, and he can take no remembrance of her away from there. His heart is lifeless with her image frozen within; but if it thaws, her beautiful image fades.

5. Der Lindenbaum (The Linden Tree)

- He comes to the linden tree, with its pale flowers and heart-shaped leaves, that stands at the gate. In the shade of this tree he has dreamt many beautiful dreams, and in the bark he has carved words of love. It was his favourite place. Now he passes it with his eyes shut, even though it is deepest night, but the branches rustle to him, 'Come here old comrade, find your rest here'. A gust of wind blows his hat off, and many hours afterwards he remembers the tree, and it seems to say 'You should have found your rest here.' It is a tacit invitation to suicide. (In Die Schöne Müllerin by the same author the rejected lover actually drowns himself and finds rest in the friendly brook where he dies.)

6. Wasserflut (Torrent)

- He weeps copiously and his tears fall in the snow. When the Spring comes the snow will melt and flow into the river, and will carry his tears to the house of his beloved.

7. Auf dem Flusse (On the River)

- The river, usually busy and bubbling, is locked in frozen darkness and lies drearily spread out under the ice. He will write her name, and the date of their first meeting, in the ice with a sharp stone. The river is a likeness of his heart: it beats and swells under the hard frozen surface.

8. Rückblick (Retrospect)

- His feet are freezing as the soles of his boots are out: but he is eager to leave the town, and he stumbles over every stone. The crows knock the snow off the eaves onto his hat from every house he passes. But when he first came to that inconstant town, larks and nightingales sang at the windows, the lime-trees blossomed, the streams ran clear, and a pair of maiden's eyes shone on him and stole his heart away. When he thinks of that happy day, he longs to walk back along the road to the house where she lives.

9. Irrlicht (Will o' the wisp)

- The will-o'-the-wisp has led him astray from the road in the darkness: but he is always going off the road, for our joy and sorrow alike are merely sports to delude us. He follows a track down the crag side: all roads lead to their goal, every spring flows to the sea, and every sorrow leads to its grave.

10. Rast (Rest)

- He reaches a charcoal-burner's hut and, worn out by his long trek through the snowstorm with a heavy backpack, he lies down to rest. In the quiet his cuts and bruises sting sorely.

11. Frühlingstraum (Dream of Springtime)

- He dreams he is wandering through meadows full of flowers and bird-song in May: he heard the cock's crow and opened his eyes, but it was a raven calling in the cheerless darkness. Who could draw the flowers of ice he can see on the windows? He dreams again, of love, and a maiden's kiss, and the joy and bliss of love, but again the crowing wakes him and he sits up alone. He tries to sleep again: when will the leaves at the window be green - when will he hold his beloved in his arms again?

12. Einsamkeit (Loneliness/Solitude)

- He wanders along the busy road ungreeted. Why is the sky so calm and the world so bright? Even in the tempest he was not so lonely as this.

13. Die Post (The Post)

- His heart leaps up as the post-horn sounds: they are not bringing him a letter, but it has come from the town, and he will ask if there is news of the beloved.

14. Der greise Kopf (The Grey Head)

- The frost in his hair made him think he was going grey, but now it has thawed and his hair is still black. He has heard that some people go grey overnight with sorrow, but though he has felt that sorrow, it has not happened to him.

15. Die Krähe (The Crow)

- A crow has followed him all along the way from the town. Is it waiting for him to die, so that it can eat him? It won't be long, let it keep him company to the end.

16. Letzte Hoffnung (Last Hope)

- He wanders among the trees and fixes his gaze on one leaf, which seems to hold his fate. It is a token: if it should fall from the branch, his hope will fall. His heart sinks, and his soul weeps the loss of everything.

17. Im Dorfe (In the Village)

- People are asleep in the village and the dogs are barking. They dream of many things and have their rest. Let the dogs drive him away so that he does not rest with them - he is finished with all dreaming.

18. Der stürmische Morgen (The Stormy Morning)

- The tempest has driven the clouds about the sky, and the fiery sun darts between them. It is like his heart, a cold, wild winter.

19. Täuschung (Deception)

- A light on the dark and icy road at night, might be a warm place to stay, or the deception of a beautiful face.

20. Der Wegweiser (The Signpost)

- Straying restlessly away from the roads, he still seeks rest. There is always a signpost in front of him, pointing to the road from which no wanderer returns. Death?

21. Das Wirtshaus (The Inn)

- The 'wayside inn' is a lonely graveyard where he hopes to find rest at last. The wreaths are the tavern sign, inviting him in. But no - all the rooms are taken, and he must carry on, as he tells his faithful walking staff.

22. Mut (Courage)

- As the wind blows snow in his face, he sings loudly to silence his thoughts of sorrow, so that he cannot hear or feel them. With his trusty staff and cheerful song he'll just keep going on.

23. Die Nebensonnen (The Phantom Suns)

- He used to see three suns, but two of them have turned away to shine upon another, and now he sees only one, and he wishes that would pass away and leave him to the darkness. The appearance of three suns is an actual meteorological phenomenon.

24. Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man)

- At the end of the village he finds the old barefoot hurdy-gurdy man, winding away his tunes, but no one has given him a penny, or listens, and even the dogs growl at him. But he just carries on playing, and the poet thinks he will cast in his lot with him.

Reworkings by others

- Franz Liszt transcribed half the songs in the cycle for piano and may have intended to do them all.[13]

- Leopold Godowsky made a number of piano transcriptions of Schubert songs; the only one from Winterreise was the first song, "Gute Nacht".[14]

- Hans Zender orchestrated a version of the cycle in 1993, altering the music in the process.

- Jens Josef created in 2001 a version for tenor and string quartet. It was recorded by Christian Elsner and the Henschel Quartet in 2002,[15] and performed in 2004 by Peter Schreier and the Dresdner Streichquartett.[16]

- John Neumeier made a ballet to Winterreise on his Hamburg Ballet company in December 2001.[17]

- Oboist Normand Forget made a unique chamber version for accordion and wind quintet including bass clarinet, oboe d'amore and baroque horn, recorded in September 2007 by tenor Christoph Prégardien, accordionist Joseph Petric, and the Montréal ensemble Pentaèdre.[18]

- The deaf actor Horst Dittrich translated the cycle of poems into Austrian Sign Language in 2007 and presented it on stage in a production of ARBOS – Company for Music and Theatre directed by Herbert Gantschacher, with Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano), in 2008 in Vienna and Salzburg and in 2009 in Villach (Austria).[19]

- Rick Burkhardt, Alec Duffy and Dave Malloy created an Obie award-winning theatrical adaptation of the cycle, Three Pianos, which played at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater and New York Theater Workshop in 2010 and the American Repertory Theater in 2011.[20]

- Matthias Loibner, inspired by "Der Leiermann", the last song of Winterreise, arranged the cycle for voice and hurdy-gurdy, and recorded it in 2010 with soprano Nataša Mirković - De Ro.[21]

Editions

Besides re-ordering Müller's songs, Schubert made a few changes to the words: verse 4 of "Erstarrung" in Müller's version read [Schubert's text bracketed]: "Mein Herz ist wie erfroren [erstorben]" ("frozen" instead of "dead"); "Irrlicht" verse 2 read "...unsre Freuden, unsre Wehen [Leiden]" ("pains" instead of "sorrows") and "Der Wegweiser" verse 3 read "Weiser stehen auf den Strassen [Wegen]" ("roads" instead of "paths"). These have all been restored in Mandyczewski's edition (the widely available Dover score) and are offered as alternative readings in Fischer-Dieskau's revision of Max Friedländer's edition for Peters. A few of the songs differ in the autograph and a copy with Schubert's corrections. "Wasserflut" was transposed by Schubert from f♯ to e without alteration; "Rast" moved from d to c and "Einsamkeit" from d to b, both with changes to the vocal line; "Mut" was transposed from a to g; "Der Leiermann" was transposed from b to a. The most recent scholarly edition of Winterreise is the one included as part of the Bärenreiter New Schubert Edition,[5] edited by Walther Dürr, Volume 3, which offers the songs in versions for high, medium and low voices. In this edition the key relationships are preserved: only one transposition is applied to the whole cycle.

The following table names the keys used in different editions. Major keys are shown with upper case letters, and minor keys with lower case letters.

| Song | Autograph & copy | Peters Edition of Friedländler (1884) | Schirmer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autograph | Tieferer Stimme | Tiefer Alt oder Baß | Low | |

| 1. Gute Nacht | d | b♭ | a | c |

| 2. Die Wetterfahne | a | f | d | f |

| 3. Gefror'ne Thränen | f | d | b | d |

| 4. Erstarrung | c | g | g | a |

| 5. Der Lindenbaum | E | D | C | E |

| 6. Wasserflut | f♯, changed to e | c | b | c♯ |

| 7. Auf dem Flusse | e | c | a | c |

| 8. Rückblick | g | e♭ | d | e |

| 9. Irrlicht | b | g | f | g |

| 10. Rast | d, changed to c | a | g | a |

| 11. Frühlingstraum | A | F | F | G |

| 12. Einsamkeit | d, changed to b | a | g | b |

| 13. Die Post | E♭ | B | G | B♭ |

| 14. Der greise Kopf | c | a | a | c |

| 15. Die Krähe | c | a | g | b♭ |

| 16. Letzte Hoffnung | E♭ | C | B♭ | D |

| 17. Im Dorfe | D | C | B♭ | D |

| 18. Der stürmische Morgen | d | c | b | d |

| 19. Täuschung | A | G | G | A |

| 20. Der Wegweiser | g | e♭ | d | e |

| 21. Das Wirthshaus | F | E♭ | D | F |

| 22. Mut | a, changed to g | f | d | f |

| 23. Die Nebensonnen | A | F | F | A |

| 24. Der Leiermann | b, changed to a | f | f | g |

Enduring influence

Schubert's Winterreise has had a marked influence on several key works, including Gustav Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen[22] and Benjamin Britten's Night-piece.[23] In 1991, Maury Yeston composed December Songs, a song cycle influenced by Winterreise, on commission from Carnegie Hall for its Centennial celebration.[24]

Recordings

There are numerous recordings. Before 1936 are the complete 1928 version of Hans Duhan with Ferdinand Foll and Lene Orthmann,[25] the incomplete Richard Tauber version with Mischa Spoliansky,[26] and, lastingly famous, the version of Gerhard Hüsch with Hanns Udo Müller (1933, for which an HMV limited edition subscription society was created).[27] There is a very powerful account by Peter Anders with Michael Raucheisen recorded in Berlin in 1945.[28] The Hans Hotter account with Gerald Moore (issued May 1955)[29] is very celebrated. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, among the most famous of exponents, is represented in seven versions spanning four decades:[30] three with Gerald Moore (1955 HMV,[31] 1963 HMV,[32] and 1972 DG),[33] and one each with Jörg Demus (1966, DG),[34] Daniel Barenboim (1980, DG),[35] Alfred Brendel (1986, Philips)[36] and Murray Perahia (1992, Sony Classical).[37] Olaf Bär's 1989 recording with Geoffrey Parsons on EMI classics is well regarded. At least one videotaped performance is also available. These, and the discs of Peter Pears with Benjamin Britten (issued 1965),[38] have all long been considered outstanding, although Norman Lebrecht placed the Pears/Britten coupling among "20 Recordings that Should Never Have Been Made" in his 2007 book The Life and Death of Classical Music.[39]

Highly recommended versions from the modern era include those of Ian Bostridge with Leif Ove Andsnes (2006, EMI Classics), Thomas Quasthoff with Charles Spencer (1998, RCA), Wolfgang Holzmair with Imogen Cooper (1996, Philips), Christian Gerhaher with Gerold Huber (2001, RCA Sony BMG, reedited in 2008), Mark Padmore with Paul Lewis (2009, Harmonia Mundi), and Werner Güra with Christoph Berner playing a Rönisch fortepiano of 1872 (2010, Harmonia Mundi).[40] In 2000, tenor Ian Bostridge and pianist Julius Drake made a dramatic video recording of the entire cycle.[41]

Footnotes

- ^ Reed, p. 441

- ^ Giarusso, p.26

- ^ Youens, 1991, p.21

- ^ A. Robertson. Schubert - Winterreise (1965).

- ^ Youens, 1991, p.22

- ^ Max Friedlaender, in Franz Schubert - Sammlung, 'Textrevision zu Franz Schubert's Liedern', following page 260.

- ^ W. Rehberg, Franz Schubert, 338-39.

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/tomserviceblog/2010/apr/28/schubert-syphilitic-sonata

- ^ Haywood 1939.

- ^ R. Capell, chapter on Winterreise.

- ^ a b C. Osborne, 1955.

- ^ Cited by William Mann, 1965.

- ^ Publisher's Note pp. ix-x in Franz Liszt: The Schubert Song Transcriptions for Solo Piano: Series II: The Complete Winterreise and Seven other Great Songs, 1996, Mineola, N.Y.,Dover Publications inc.

- ^ Classics Online

- ^ "Schubert: Winterreise / Christian Elsner, Henschel Quartet". arkivmusic.com. 2002. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ "Bekannte Tour durch eine neue Klangwelt" (in German). Sächsische Zeitung. 21 June 2004. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ biography of John Neumeier on Hamburg Ballet website

- ^ Pentaèdre (Danièle Bourget, Martin Charpentier, Normand Forget, Louis-Philippe Marsolais, Mathieu Lussier). ATMA ACD2 2546 [1] This version was performed by at the Hohenems Schubertiade(2009) and in the Berlin Philharmonik Chambermusic series in 2013 with the Berlin Philharmonic Woodwind Quintet.

- ^ [2] "Illusion" by Franz Schubert and Wilhelm Müller on stage by Horst Dittrich (Austrian Sign Language), Rupert Bergmann (bass-baritone) and Gert Hecher (piano)

- ^ [3]

- ^ "Schubert: Winterreise Nataša Mirković - De Ro (tenor) Matthias Loibner (hurdy-gurdy)". Nov 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Schroeder, David P. Our Schubert: his enduring legacy The Scarecrow Press, 2009: p. 174

- ^ Keller, Hans. Film music and beyond: writing on music and the screen, 1946-59. Ed. Christopher Wintle. Plumbago Books, 2006: p. 96

- ^ "About Maury Yeston". About Maury Yeston's website. Retrieved 1 July 22013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ German HMV, 24 sides, ER 270-272, 274-276, ES 383-386, 392-393: see Darrell 1936, p. 414. CD: Prestige Recordings, HT S004.

- ^ Polydor-Odeon, only songs 1,5,6,8,11,13,15,18,20,21,22,24); cf. Darrell 1936, p. 414.

- ^ Blom, 1933. Reissued from HMV DA 1344-1346 (10") and DB 2039-2044 (12"), World Records SH 651-652 transfer by Keith Hardwick for EMI 1980.

- ^ See Joseph Horowitz review in NYT [4]

- ^ Columbia CXS 1222, CX 1223, reissued as Seraphim IC-6051 with Schwanengesang, etc.

- ^ James Jolly (30 November 1999). "Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Schubert's Winterreise. How Gramophone followed this winter's journey". Gramophone. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ HMV ALP 1298/9, recorded 13-14 January, 1955, issued November 1955; following Die schöne Müllerin issued 1953

- ^ HMV ALP 2001/2, ASD 551/2, recorded 16-17 November, 1962, sleeve notes by William Mann; following Die schöne Müllerin issued 1962: Reissued in A Schubert Anthology, EMI/HMV SLS 840 box set, BOX 84001-84003.

- ^ DGG LP 2720 059, CD 437 237-2, recorded August 1971

- ^ DGG LP 39201/2, recorded May 1965

- ^ DGG LP 2707 118, CD 439 432-2, recorded 1979

- ^ Philips CD 411 463-2, recorded July 1985

- ^ Sony Classical CD SK48237, recorded July 1990

- ^ Decca Stereo, SET 270-271.

- ^ Lebrecht, Norman. The Life and Death of Classical Music. New York: Anchor Books, 2007, p. 289.

- ^ Hugh Canning (7 May 2010). "Schubert: Winterreise Werner Güra (tenor), Christoph Berner (piano)". The Times. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Ian Bostridge (tenor) Julius Drake (piano)". Retrieved 14 July 2012.

References

- Blom, Eric, Schubert's "Winterreise", Foreword and analytical notes, (The "Winterreise" Society, Gramophone Company, Ltd, London 1933), 32 pp.

- Capell, Richard (1928). Schubert's Song. London: Ernest Benn.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Deutsch, Otto Erich (1957). Schubert: Die Erinnerungen seiner Freunde. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Deutsch, Otto Erich (1964). Franz Schubert: Zeugnisse seiner Zeitgenossen. Frankfort: Fischer-Verlag.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Dorschel, Andreas, 'Wilhelm Müllers Die Winterreise und die Erlösungsversprechen der Romantik', in: The German Quarterly LXVI (1993), nr. 4, pp. 467-476.

- (E.M.G.), The Art of Record Buying (EMG, London 1960).

- Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich (1977). Schubert's Songs. New York: Knopf.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Giarusso, Richard (2008). "Beyond the Leiermann". [[6] The Unknown Schubert]. Ashgate.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Haywood, Ernest, 'Terrifying Songs', Radio Times 20 January 1939.

- Mann, William, Schubert Winterreise, Sleeve notes HMV ASD 552 (Gramophone Co. Ltd 1955).

- Moore, Gerald (1975). The Schubert Song Cycles - with thoughts on performance. London: Hamish Hamilton.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Müller, Wilhelm, Aus dem hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten, II: Lieder des Lebens und der Liebe.

- Neuman, Andrés, El viajero del siglo (Traveller of the Century). Madrid: Alfaguara, 2009. XII Alfaguara Award of novel.

- Osborne, Charles, Schubert Winterreise, Sleeve notes HMV ALPS 1298/9 (Gramophone Co. Ltd 1955).

- Reed, John (1985). The Schubert Song Companion. New York: Universe Books. ISBN 0-87663-477-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Rehberg, Walter and Paul (1946). Schubert: Sein Leben und Werk. Zurich: Artemis-Verlag.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Robertson, Alec, Schubert, Winterreise, Brochure accompanying Decca SET 270-271 (Decca Records, London 1965).

- Schubert, Franz, Sammlung der Lieder kritisch revidirt von Max Friedländer, Band I, Preface by Max Müller (Peters, Leipzig).

- Youens, Susan (1991). Retracing a Winter's Journey: Schubert's Winterreise. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Free scores by Winterreise at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- The working ms at Schubert Online

- German texts and English translations

- Performance by Randall Scarlata (baritone) and Jeremy Denk (piano) part 1 and part 2 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in MP3 format

- Complete performance by soprano Lotte Lehmann

- Winterreise (MIDI)

- A Web site about Winterreise by Margo Briessinck

- The complete text, spoken in German, at librivox.org (N. 20)