Gondola: Difference between revisions

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

The [[manga|Japanese manga]] ''[[Aria (manga)|Aria]]'' follows a young woman named Akari as she trains as an apprentice gondolier in Neo-Venezia, a city on a terraformed Mars based on [[Venice]]. |

The [[manga|Japanese manga]] ''[[Aria (manga)|Aria]]'' follows a young woman named Akari as she trains as an apprentice gondolier in Neo-Venezia, a city on a terraformed Mars based on [[Venice]]. |

||

In an episode of The Scooby-Doo show, 'A Menace in Venice', the gang goes to visit their friend Antonio in Venice, Italy, and finds that he is haunted by the ghost of an ancestor, the Ghostly Gondolier, who seeks to steal the family heirloom Antonio wears. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 14:46, 11 August 2014

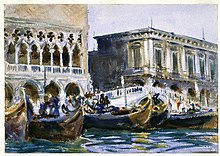

The gondola is a traditional, flat-bottomed Venetian rowing boat, well suited to the conditions of the Venetian lagoon. The gondola is propelled like punting, except an oar is used instead of a pole.[1] For centuries gondolas were the chief means of transportation and most common watercraft within Venice. In modern times the iconic boats still have a role in public transport in the city, serving as traghetti (ferries) over the Grand Canal. They are also used in special regattas (rowing races) held amongst gondoliers. Their primary role today, however, is to carry tourists on rides at fixed rates.[2]

History and usage

The gondola is propelled by a person (the gondolier) who stands facing the bow and rows with a forward stroke, followed by a compensating backward stroke. Contrary to popular belief, the gondola is never poled like a punt as the waters of Venice are too deep. Until the early 20th century, as many photographs attest, gondolas were often fitted with a "felze", a small cabin, to protect the passengers from the weather or from onlookers. Its windows could be closed with louvered shutters—the original "venetian blinds". After the elimination of the traditional felze—possibly in response to tourists complaining that it blocked the view—there survived for some decades a kind of vestigial summer awning, known as the "tendalin" (these can be seen on gondolas as late as the mid-1950s, in the film Summertime). While in previous centuries gondolas could be many different colors, a sumptuary law of Venice required that gondolas should be painted black, and they are customarily so painted now.

It is estimated that there were eight to ten thousand gondolas during the 17th and 18th century. There are just over four hundred in active service today, virtually all of them used for hire by tourists. Those few that are in private ownership are either hired out to Venetians for weddings or used for racing.[3] Even though the Gondola by now has become a widely publicized icon of Venice, in the times of the Republic of Venice it was by far not the only means of transportation: on the map of Venice created by Jacopo de' Barbari in 1500 only a fraction of the boats are gondolas, the majority of boats are batellas, caorlinas, galleys and other boats - by now only a handful of batellas survive, and caorlinas are used for racing only.

During their heyday as a means of public transports, teams of four men—three oarsmen and a fourth person, primarily shore-based and responsible for the booking and administration of the gondola (Il Rosso Riserva)—would share ownership of a gondola. However as the gondolas became more of a tourist attraction than a mode of public transport all but one of these cooperatives and their offices have closed. The category is now protected by the Institution for the Protection and Conservation of Gondolas and Gondoliers,[4] headquartered in the historical center of Venice.

The historical gondola was quite different from its modern evolution- the paintings of Canaletto and others show a much lower prow, a higher "ferro", and usually two rowers. The banana-shaped modern gondola was developed only in the 19th century by the boat-builder Tramontin, whose heirs still run the Tramontin boatyard. The construction of the gondola continued to evolve until the mid-20th century, when the city government prohibited any further modifications.

The oar or rèmo is held in an oar lock known as a fórcola. The forcola is of a complicated shape, allowing several positions of the oar for slow forward rowing, powerful forward rowing, turning, slowing down, rowing backwards, and stopping. The ornament on the front of the boat is called the fèrro (meaning iron) and can be made from brass, stainless steel, or aluminium. It serves as decoration and as counterweight for the gondolier standing near the stern.

Gondolas are handmade using 8 different types of wood (fir, oak, cherry, walnut, elm, mahogany, larch and lime) and are composed of 280 pieces.[5][unreliable source?] The oars are made of beech wood. The port side of the gondola is made longer than the starboard side. This asymmetry causes the gondola to resist the tendency to turn towards the left at the forward stroke. It is a common misconception[citation needed] that the gondola is a paddled vessel when the correct term is rowed, as in "I rowed my gondola to work."

The profession of gondolier is controlled by a guild, which issues a limited number of licenses (425) granted after periods of training and apprenticeship, and a major comprehensive exam[6] which tests knowledge of Venetian history and landmarks, foreign language skills, and practical skills in handling the gondola[7] typically necessary in the tight spaces of Venetian canals.

Every detail of the gondola has its own symbolism. The iron prow-head of the gondola, called "fero da prorà” or “dol fin“, is needed to balance the weight of the gondolier at the stern and has an “S” shape symbolic of the twists in the Canal Grande. Under the main blade there is a kind of comb with six teeth or prongs (“rebbi “) standing for the six “sestieri” of Venice. A kind of tooth juts out backwards toward the centre of the gondola symbolises the island of Giudecca. Sometimes three friezes can be seen in-between the six prongs, pairing the ses tien, indicating the three main bridges in the city: the Rialto Bridge, the Ponte dell’Accademia and the Ponte degli Scalzi.[8]

The gondola is also one of the vessels typically used in both ceremonial and competitive regattas, rowing races held amongst gondoliers using the technique of Voga alla Veneta.

The origin of the word "gondola" has never been satisfactorily established, despite many theories.[9]

In August 2010, Giorgia Boscolo became Venice's first female gondolier.[10]

References in literature and history

Mark Twain visited Venice in the summer of 1867. He dedicated much of The Innocents Abroad, chapter 23 to describing the curiosity of urban life with gondolas and gondoliers.

The first act of Gilbert and Sullivan's two-act comic operetta The Gondoliers is set in Venice, and the show's two protagonists (as well as its men's chorus) are of the eponymous profession, even though the political irony that makes up the core of the show has much more to do with British society than Venice.

The Japanese manga Aria follows a young woman named Akari as she trains as an apprentice gondolier in Neo-Venezia, a city on a terraformed Mars based on Venice.

In an episode of The Scooby-Doo show, 'A Menace in Venice', the gang goes to visit their friend Antonio in Venice, Italy, and finds that he is haunted by the ghost of an ancestor, the Ghostly Gondolier, who seeks to steal the family heirloom Antonio wears.

See also

- Alexandra Hai

- Floating battery

- Rower woman

- Sandolo

- Sculling

- Water taxi

- Watercraft rowing

- Gondola_(magazine)

Notes

- ^ "Le barche". Città di Venezia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Official fares for gondola rides in Venice

- ^ R. Davis & G. Marvin, Venice, the Tourist Maze pp. 133-59

- ^ Official site for the Institute of the preservation of the gondola e protection of gondoliers

- ^ Gondola Article

- ^ Daily Telegraph article "Gondolier course in Venice: stick your oar in"

- ^ Corriere della Sera article (in Italian)

- ^ The history of the gondola and its symbolism

- ^ Daily Telegraph article on history of the gondola

- ^ First lady joins official ranks of Venice's gondoliers

References

- Horatio Brown, chapter 'The Gondola' in Life on the Lagoons (1884 and later editions)

- Wooden Boat, The Venetian Gondola, April 1977. Penzo, Gilberto; La Gondola, 1999.