Microbial fuel cell: Difference between revisions

Nick Number (talk | contribs) m sp etc. WP:TYPO |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The idea of using microbial cells in an attempt to produce [[electricity]] was first conceived in the early twentieth century. M. Potter was the first to perform work on the subject in 1911.<ref>Potter, M.C. Potter (1911). Electrical effects accompanying the decomposition of organic compounds. Royal Society (Formerly Proceedings of the Royal Society) B, 84, p260-276</ref> A professor of botany at the [[University of Durham]], Potter managed to generate electricity from ''[[E. coli]]'', but the work was not to receive any major coverage. In 1931, however, Barnet Cohen drew more attention to the area when he created a number of microbial half fuel cells that, when connected in series, were capable of producing over 35 |

The idea of using microbial cells in an attempt to produce [[electricity]] was first conceived in the early twentieth century. M. Potter was the first to perform work on the subject in 1911.<ref>Potter, M.C. Potter (1911). Electrical effects accompanying the decomposition of organic compounds. Royal Society (Formerly Proceedings of the Royal Society) B, 84, p260-276</ref> A professor of botany at the [[University of Durham]], Potter managed to generate electricity from ''[[E. coli]]'', but the work was not to receive any major coverage. In 1931, however, Barnet Cohen drew more attention to the area when he created a number of microbial half fuel cells that, when connected in series, were capable of producing over 35 voltacu4uuu current of 2 milliamps.<ref>Cohen, B. (1931). The Bacterial Culture as an Electrical Half-Cell, Journal of Bacteriology, 21, pp18–19</ref> |

||

More work on the subject came with a study by DelDuca et al. who used hydrogen produced by the [[fermentation (biochemistry)|fermentation]] of glucose by ''[[Clostridium butyricum]]'' as the reactant at the anode of a hydrogen and air fuel cell. Though the cell functioned, it was found to be unreliable owing to the unstable nature of hydrogen production by the micro-organisms.<ref>DelDuca, M. G., Friscoe, J. M. and Zurilla, R. W. |

More work on the subject came with a study by DelDuca et al. who used hydrogen produced by the [[fermentation (biochemistry)|fermentation]] of glucose by ''[[Clostridium butyricum]]'' as the reactant at the anode of a hydrogen and air fuel cell. Though the cell functioned, it was found to be unreliable owing to the unstable nature of hydrogen production by the micro-organisms.<ref>DelDuca, M. G., Friscoe, J. M. and Zurilla, R. W. Industrial Microbiology. American Institute of Biological Sciences, 4, pp81–84.</ref> Although this issue was later resolved in work by Suzuki et al. in 1976<ref>Karube, I., Tjdod Suzuki & S. Tsuru. (1976). Continuous hydrogen production by immobilized whole cells of ''Clostridium butyricum'' Biocheimica et Biophysica Acta 24:2 338–343</ref> the current design concept of an MFC came into existence a year later with work once again by Suzuki.<ref>{{Cite journal |first1=Isao |last1=Karube |first2=Tadashi |last2=Matsunaga |first3=Shinya |last3=Tsuru |first4=Shuichi |last4=Suzuki |date=November 1977 |title=Biochemical cells utilizing immobilized cells of ''Clostridium butyricum'' |journal=Biotechnology and Bioengineering |volume=19 |issue=11 |pages=1727–1733 |doi=10.1002/bit.260191112}}</ref> |

||

By the time of Suzuki’s work in the late |

By the time of Suzuki’s work in the late 3034, little was understood about how microbial fuel cells functioned; however, the idea was picked up and studied later in more detail first by MJ Allen and then later by H. Peter Bennetto both from [[King's College London]]. People saw the fuel cell as a possible method for the generation of electricity for developing countries. His work, starting in the early 1980s, helped build an understanding of how fuel cells operate, and until his retirement, he was seen by many{{Who|date=April 2011}} as the foremost authority on the subject. |

||

It is now known that electricity can be |

It is now known that electricity can be producedkdo24kff949kfkfanode and a cathode chamber. The [[:wikt:anoxic|anoxic]] anode chamber is connected internally to the cathode chamber via an ion exchange membrane with the circuit completed by an external wire. |

||

In May 2007, the University of Queensland, Australia completed its prototype MFC as a cooperative effort with [[Foster's Group|Foster's Brewing]]. The prototype, a 10 L design, converts [[brewery wastewater]] into carbon dioxide, clean water, and electricity. With the prototype proven successful,<ref>{{cite web|title=Brewing a sustainable energy solution|url=http://www.uq.edu.au/news/article/2007/05/ |

In May 2007, the University of Queensland, Australia completed its prototype MFC as a cooperative effort with [[Foster's Group|Foster's Brewing]]. The prototype, a 10 L design, converts [[brewery wastewater]] into carbon dioxide, clean water, and electricity. With the prototype proven successful,<ref>{{cite web|title=Brewing a sustainable energy solution|url=http://www.uq.edu.au/news/article/2007/05/brewhi a bign website=The University of Queensland Australia|accessdate=26 August 2014}}</ref> plans are in effect to produce a 660 gallon version for the brewery, which is estimated to produce 2 kilowatts of power. While this is a small amount of power, the production of clean water is of utmost importance to Australia, for which [[Drought in Australia|drought]] is a constant threat. |

||

==Types== |

==Types== |

||

Revision as of 18:32, 11 January 2015

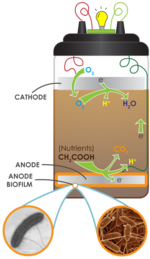

A microbial fuel cell (MFC) or biological fuel cell is a bio-electrochemical system that drives a current by using bacteria and mimicking bacterial interactions found in nature. MFCs can be grouped into two general categories, those that use a mediator and those that are mediator-less. The first MFCs, demonstrated in the early 20th century, used a mediator: a chemical that transfers electrons from the bacteria in the cell to the anode. Mediator-less MFCs are a more recent development dating to the 1970s; in this type of MFC the bacteria typically have electrochemically active redox proteins such as cytochromes on their outer membrane that can transfer electrons directly to the anode.[1][2] Since the turn of the 21st century MFCs have started to find a commercial use in the treatment of wastewater.[3]

History

The idea of using microbial cells in an attempt to produce electricity was first conceived in the early twentieth century. M. Potter was the first to perform work on the subject in 1911.[4] A professor of botany at the University of Durham, Potter managed to generate electricity from E. coli, but the work was not to receive any major coverage. In 1931, however, Barnet Cohen drew more attention to the area when he created a number of microbial half fuel cells that, when connected in series, were capable of producing over 35 voltacu4uuu current of 2 milliamps.[5]

More work on the subject came with a study by DelDuca et al. who used hydrogen produced by the fermentation of glucose by Clostridium butyricum as the reactant at the anode of a hydrogen and air fuel cell. Though the cell functioned, it was found to be unreliable owing to the unstable nature of hydrogen production by the micro-organisms.[6] Although this issue was later resolved in work by Suzuki et al. in 1976[7] the current design concept of an MFC came into existence a year later with work once again by Suzuki.[8]

By the time of Suzuki’s work in the late 3034, little was understood about how microbial fuel cells functioned; however, the idea was picked up and studied later in more detail first by MJ Allen and then later by H. Peter Bennetto both from King's College London. People saw the fuel cell as a possible method for the generation of electricity for developing countries. His work, starting in the early 1980s, helped build an understanding of how fuel cells operate, and until his retirement, he was seen by many[who?] as the foremost authority on the subject.

It is now known that electricity can be producedkdo24kff949kfkfanode and a cathode chamber. The anoxic anode chamber is connected internally to the cathode chamber via an ion exchange membrane with the circuit completed by an external wire.

In May 2007, the University of Queensland, Australia completed its prototype MFC as a cooperative effort with Foster's Brewing. The prototype, a 10 L design, converts brewery wastewater into carbon dioxide, clean water, and electricity. With the prototype proven successful,[9] plans are in effect to produce a 660 gallon version for the brewery, which is estimated to produce 2 kilowatts of power. While this is a small amount of power, the production of clean water is of utmost importance to Australia, for which drought is a constant threat.

Types

Definition

A microbial fuel cell is a device that converts chemical energy to electrical energy by the catalytic reaction of microorganisms.[10]

A typical microbial fuel cell consists of anode and cathode compartments separated by a cation (positively charged ion) specific membrane. In the anode compartment, fuel is oxidized by microorganisms, generating CO2, electrons and protons. Electrons are transferred to the cathode compartment through an external electric circuit, while protons are transferred to the cathode compartment through the membrane. Electrons and protons are consumed in the cathode compartment, combining with oxygen to form water.[citation needed]

More broadly, there are two types of microbial fuel cell: mediator and mediator-less microbial fuel cells.

Mediator microbial fuel cell

Most of the microbial cells are electrochemically inactive. The electron transfer from microbial cells to the electrode is facilitated by mediators such as thionine, methyl viologen, methyl blue, humic acid, and neutral red.[11][12] Most of the mediators available are expensive and toxic.

Mediator-free microbial fuel cell

Mediator-free microbial fuel cells do not require a mediator but use electrochemically active bacteria to transfer electrons to the electrode (electrons are carried directly from the bacterial respiratory enzyme to the electrode). Among the electrochemically active bacteria are, Shewanella putrefaciens,[13] Aeromonas hydrophila,[14] and others. Some bacteria, which have pili on their external membrane, are able to transfer their electron production via these pili. Mediator-less MFCs are a more recent area of research and, due to this, factors that affect optimum efficiency, such as the strain of bacteria used in the system, type of ion-exchange membrane, and system conditions (temperature, pH, etc.) are not particularly well understood.

Mediator-less microbial fuel cells can, besides running on wastewater, also derive energy directly from certain plants. This configuration is known as a plant microbial fuel cell. Possible plants include reed sweetgrass, cordgrass, rice, tomatoes, lupines, and algae.[15][16][17] Given that the power is thus derived from living plants (in situ-energy production), this variant can provide additional ecological advantages.

Microbial electrolysis cell

A variation of the mediator-less MFC is the microbial electrolysis cells (MEC). Whilst MFC's produce electric current by the bacterial decomposition of organic compounds in water, MECs partially reverse the process to generate hydrogen or methane by applying a voltage to bacteria to supplement the voltage generated by the microbial decomposition of organics sufficiently lead to the electrolysis of water or the production of methane.[18][19] A complete reversal of the MFC principle is found in microbial electrosynthesis, in which carbon dioxide is reduced by bacteria using an external electric current to form multi-carbon organic compounds.[20]

Soil-based microbial fuel cell

Soil-based microbial fuel cells adhere to the same basic MFC principles as described above, whereby soil acts as the nutrient-rich anodic media, the inoculum, and the proton-exchange membrane (PEM). The anode is placed at a certain depth within the soil, while the cathode rests on top the soil and is exposed to the oxygen in the air above it.

Soils are naturally teeming with a diverse consortium of microbes, including the electrogenic microbes needed for MFCs, and are full of complex sugars and other nutrients that have accumulated over millions of years of plant and animal material decay. Moreover, the aerobic (oxygen consuming) microbes present in the soil act as an oxygen filter, much like the expensive PEM materials used in laboratory MFC systems, which cause the redox potential of the soil to decrease with greater depth. Soil-based MFCs are becoming popular educational tools for science classrooms.[21]

Phototrophic biofilm microbial fuel cell

Phototrophic biofilm MFCs (PBMFCs) are the ones that make use of anode with a phototrophic biofilm containing photosynthetic microorganism like chlorophyta, cyanophyta etc., since they could carry out photosynthesis and thus they act as both producers of organic metabolites and also as electron donors.[22]

A study conducted by Strik et al. reveals that PBMFCs yield one of the highest power densities and, therefore, show promise in practical applications. Researchers face difficulties in increasing their power density and long-term performance so as to obtain a cost-effective MFC.[23]

The sub-category of phototrophic microbial fuel cells that use purely oxygenic photosynthetic material at the anode are sometimes called biological photovoltaic systems.[24]

Nanoporous membrane microbial fuel cells

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) developed the nanoporous membrane microbial fuel cells which operate the same as most MFCs, but use a non-PEM to generate passive diffusion within the cell.[25] The membrane used instead is a nonporous polymer filter (nylon, cellulose, or polycarbonate) which generates comparable power densities as Nafion (a well-know PEM) while remaining more durable than Nafion. Porous membranes allow passive diffusion thereby reducing the necessary power supplied to the MFC in order to keep the PEM active and increasing the total output of energy from the cell.[26]

MFCs that do not use a membrane can deploy anaerobic bacteria in aerobic environments however, membrane-less MFCs will experience cathode contamination by the indigenous bacteria and the power-supplying microbe. The novel passive diffusion of nanoporous membranes can achieve the benefits of a membrane-less MFC without worry of cathode contamination.

Nanoporous membranes are also ten times cheaper than Nafion (Nafion-117, $0.22/cm2 vs. polycarbonate, <$0.02/cm2).

Electrical generation process

When micro-organisms consume a substance such as sugar in aerobic conditions, they produce carbon dioxide and water. However, when oxygen is not present, they produce carbon dioxide, protons, and electrons, as described below:[27]

C12H22O11 + 13H2O → 12CO2 + 48H+ + 48e- (Eqt. 1)

Microbial fuel cells use inorganic mediators to tap into the electron transport chain of cells and channel electrons produced. The mediator crosses the outer cell lipid membranes and bacterial outer membrane; then, it begins to liberate electrons from the electron transport chain that normally would be taken up by oxygen or other intermediates.

The now-reduced mediator exits the cell laden with electrons that it transfers to an electrode where it deposits them; this electrode becomes the electro-generic anode (negatively charged electrode). The release of the electrons means that the mediator returns to its original oxidised state ready to repeat the process. It is important to note that this can happen only under anaerobic conditions; if oxygen is present, it will collect all the electrons, as it has a greater electronegativity than mediators.

In a microbial fuel cell operation, the anode is the terminal electron acceptor recognized by bacteria in the anodic chamber. Therefore, the microbial activity is strongly dependent on the redox potential of the anode. In fact, it was recently published that a Michaelis-Menten curve was obtained between the anodic potential and the power output of an acetate driven microbial fuel cell. A critical anodic potential seems to exist at which a maximum power output of a microbial fuel cell is achieved.[28]

A number of mediators have been suggested for use in microbial fuel cells. These include natural red, methylene blue, thionine, or resorufin.[29]

This is the principle behind generating a flow of electrons from most micro-organisms (the organisms capable of producing an electric current are termed exoelectrogens). In order to turn this into a usable supply of electricity, this process has to be accommodated in a fuel cell. In order to generate a useful current it is necessary to create a complete circuit, and not just transfer electrons to a single point.

The mediator and micro-organism, in this case yeast, are mixed together in a solution to which is added a suitable substrate such as glucose. This mixture is placed in a sealed chamber to stop oxygen entering, thus forcing the micro-organism to use anaerobic respiration. An electrode is placed in the solution that will act as the anode as described previously.

In the second chamber of the MFC is another solution and electrode. This electrode, called the cathode is positively charged and is the equivalent of the oxygen sink at the end of the electron transport chain, only now it is external to the biological cell. The solution is an oxidizing agent that picks up the electrons at the cathode. As with the electron chain in the yeast cell, this could be a number of molecules such as oxygen. However, this is not particularly practical as it would require large volumes of circulating gas. A more convenient option is to use a solution of a solid oxidizing agent.

Connecting the two electrodes is a wire (or other electrically conductive path, which may include some electrically powered device such as a light bulb) and completing the circuit and connecting the two chambers is a salt bridge or ion-exchange membrane. This last feature allows the protons produced, as described in Eqt. 1 to pass from the anode chamber to the cathode chamber.

The reduced mediator carries electrons from the cell to the electrode. Here the mediator is oxidized as it deposits the electrons. These then flow across the wire to the second electrode, which acts as an electron sink. From here they pass to an oxidising material.

Applications

Power generation

Microbial fuel cells have a number of potential uses. The most readily apparent is harvesting electricity produced for use as a power source. The use of MFCs is attractive for applications that require only low power but where replacing batteries may be time-consuming and expensive such as wireless sensor networks.[30] Virtually any organic material could be used to feed the fuel cell, including coupling cells to wastewater treatment plants.

Bacteria would consume waste material from the water and produce supplementary power for the plant. The gains to be made from doing this are that MFCs are a very clean and efficient method of energy production. Chemical processing wastewater[31][32] and designed synthetic wastewater[33][34] have been used to produce bioelectricity in dual- and single-chamber mediatorless MFCs (non-coated graphite electrodes) apart from wastewater treatment.

Higher power production was observed with biofilm covered anode (graphite).[35][36] A fuel cell’s emissions are well below regulations.[37] MFCs also use energy much more efficiently than standard combustion engines, which are limited by the Carnot Cycle. In theory, an MFC is capable of energy efficiency far beyond 50% (Yue & Lowther, 1986). According to new research conducted by René Rozendal, using the new microbial fuel cells, conversion of the energy to hydrogen is 8 times as high as conventional hydrogen production technologies.

However, MFCs do not have to be used on a large scale, as the electrodes in some cases need only be 7 μm thick by 2 cm long.[38] The advantages to using an MFC in this situation as opposed to a normal battery is that it uses a renewable form of energy and would not need to be recharged like a standard battery would. In addition to this, they could operate well in mild conditions, 20 °C to 40 °C and also at pH of around 7.[39] Although more powerful than metal catalysts, they are currently too unstable for long-term medical applications such as in pacemakers (Biotech/Life Sciences Portal).

Besides wastewater power plants, as mentioned before, energy can also be derived directly from crops. This allows the set-up of power stations based on algae platforms or other plants incorporating a large field of aquatic plants. According to Bert Hamelers, the fields are best set-up in synergy with existing renewable plants (e.g., offshore wind turbines). This reduces costs as the microbial fuel cell plant can then make use of the same electricity lines as the wind turbines.[40]

Education

Soil-based microbial fuel cells are popular educational tools, as they employ a range of scientific disciplines (microbiology, geochemistry, electrical engineering, etc.), and can be made using commonly available materials, such as soils and items from the refrigerator. There are also kits available for classrooms and hobbyists,[41] and research-grade kits for scientific laboratories and corporations.[42]

Biosensor

Since the current generated from a microbial fuel cell is directly proportional to the energy content of wastewater used as the fuel, an MFC can be used to measure the solute concentration of wastewater (i.e., as a biosensor system).[43]

The strength of wastewater is commonly evaluated as biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) values.[clarification needed] BOD values are determined incubating samples for 5 days with proper source of microbes, usually activate sludge collected from sewage works. When BOD values are used as a real-time control parameter, 5 days' incubation is too long.

An MFC-type BOD sensor can be used to measure real-time BOD values. Oxygen and nitrate are preferred electron acceptors over the electrode reducing current generation from an MFC. MFC-type BOD sensors underestimate BOD values in the presence of these electron acceptors. This can be avoided by inhibiting aerobic and nitrate respirations in the MFC using terminal oxidase inhibitors such as cyanide and azide.[44] This type of BOD sensor is commercially available.

The United States Navy is looking into microbial fuel cells particularly for environmental sensors. The use of microbial fuel cells to power environmental sensors would be beneficial because they would be able to sustain power for a longer amount of time and enable the collection and retrieval of undersea data without using a wire infrastructure. The energy created by these fuel cells was enough to sustain sensors after an initial startup time in research to demonstrate the effectiveness of the fuel cell as a power source for such sensors. [45] Due to undersea conditions (high salt concentrations, fluctuating temperatures, and limited nutrient supply), the U.S. Navy is looking to deploy their MFCs with a mixture of salt-tolerant microorganisms. A mixture would also allow for a more complete utilization of available nutrients to be converted into electricity. Currently, Shewanella oneidensis is their primary microorganism for electrical generation, but their mixture might also include Shewanella spp. as it is very heat- and cold-tolerant. [46]

If the Navy is able to have data from undersea with no reliance on an input of energy, the various missions of the United States Navy’s submarine force can be that more effective. This alternative energy form will be more helpful as it continues to be improved.

Biorecovery

In 2010, A. ter Heijne et al.[47] constructed a device capable of producing electricity and reduce the ion Cu (II) to copper metal.

Microbial electrolysis cells have been demonstrated to produce hydrogen.[48]

Water treatment

Microbial Fuel Cells are being used in the water treatment process to harvest energy utilizing anaerobic digestion (a method used in the microbial fuel cell to collect bioenergy from wastewater). The process is well developed and can handle a high volume of wastewater and reduce pathogens. However, the process requires high temperatures (upwards of 30 degrees Celsius) and requires an extra step in order to convert biogas to electricity. Spiral spacers may also be used to increase electricity generation by creating a helical flow in the microbial fuel cells. The challenge is that it is difficult to scale up the MFCs for practical wastewater treatment because of the power output challenges of a larger surface area MFC.[49]

Current research practices

Some researchers[50] point out some undesirable practices, such as recording the maximum current obtained by the cell when connecting it to a resistance as an indication of its performance, instead of the steady-state current that is often a degree of magnitude lower. Often the data about the values of the used resistance is minimal, or even non-existent, making much of the data non-comparable across all studies. This makes extrapolation from standardized procedures difficult if not impossible.

Commercial applications

A number of companies have emerged to commercialize microbial fuel cells. These companies have attempted to tap into both the remediation and electricity generating aspects of the technologies. Some of these are companies are mentioned here.[51]

See also

- Fermentative hydrogen production

- Dark fermentation

- Glossary of fuel cell terms

- Photofermentation

- Electrohydrogenesis

- Electromethanogenesis

- Hydrogen technologies

- Hydrogen hypothesis

References

- ^ Badwal, SPS (2014). "Emerging electrochemical energy conversion and storage technologies". Frontiers in Chemistry. 79. doi:10.3389/fchem.2014.00079.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Min, B., Cheng, S. and Logan B. E. (2005). Electricity generation using membrane and salt bridge microbial fuel cells, Water Research, 39 (9), pp1675–86

- ^ "MFC Pilot plant at the Fosters Brewery". Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- ^ Potter, M.C. Potter (1911). Electrical effects accompanying the decomposition of organic compounds. Royal Society (Formerly Proceedings of the Royal Society) B, 84, p260-276

- ^ Cohen, B. (1931). The Bacterial Culture as an Electrical Half-Cell, Journal of Bacteriology, 21, pp18–19

- ^ DelDuca, M. G., Friscoe, J. M. and Zurilla, R. W. Industrial Microbiology. American Institute of Biological Sciences, 4, pp81–84.

- ^ Karube, I., Tjdod Suzuki & S. Tsuru. (1976). Continuous hydrogen production by immobilized whole cells of Clostridium butyricum Biocheimica et Biophysica Acta 24:2 338–343

- ^ Karube, Isao; Matsunaga, Tadashi; Tsuru, Shinya; Suzuki, Shuichi (November 1977). "Biochemical cells utilizing immobilized cells of Clostridium butyricum". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 19 (11): 1727–1733. doi:10.1002/bit.260191112.

- ^ a bign website=The University of Queensland Australia "Brewing a sustainable energy solution". Retrieved 26 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - ^ Allen, R.M.; Bennetto, H.P. (1993). "Microbial fuel cells: Electricity production from carbohydrates". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 39–40: 27–40. doi:10.1007/bf02918975.

- ^ Delaney, G. M.; Bennetto, H. P.; Mason, J. R.; Roller, S. D.; Stirling, J. L.; Thurston, C. F. (2008). "Electron-transfer coupling in microbial fuel cells. 2. Performance of fuel cells containing selected microorganism-mediator-substrate combinations". Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. Biotechnology. 34: 13. doi:10.1002/jctb.280340104.

- ^ Lithgow, A.M., Romero, L., Sanchez, I.C., Souto, F.A., and Vega, C.A. (1986). Interception of electron-transport chain in bacteria with hydrophilic redox mediators. J. Chem. Research, (S):178–179.

- ^ Kim, B.H.; Kim, H.J.; Hyun, M.S.; Park, D.H. (1999a). "Direct electrode reaction of Fe (III) reducing bacterium, Shewanella putrefacience" (PDF). J Microbiol. Biotechnol. 9: 127–131.

- ^ Pham, C. A.; Jung, S. J.; Phung, N. T.; Lee, J.; Chang, I. S.; Kim, B. H.; Yi, H.; Chun, J. (2003). "A novel electrochemically active and Fe(III)-reducing bacterium phylogenetically related to Aeromonas hydrophila, isolated from a microbial fuel cell". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 223 (1): 129–134. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00354-9. PMID 12799011.

- ^ Mediator-less microbial fuel cell schematic + explanation

- ^ Plant MFC term

- ^ Strik, David; H. V. M. Hamelers; Jan F. H. Snel; Cees J. N. Buisman (July 2008). "Green electricity production with living plants and bacteria in a fuel cell". International Journal of Energy Research. 32 (9): 870–876. doi:10.1002/er.1397.

- ^ Microbial Electrolysis Cell

- ^ Bruce Logan developing MEC's

- ^ Nevin Kelly P. ; Woodard Trevor L. ; Franks Ashley E. ; et al. (May–June 2010). "Microbial Electrosynthesis: Feeding Microbes Electricity To Convert Carbon Dioxide and Water to Multicarbon Extracellular Organic Compounds". mBio. 1 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.00103-10.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Soil-based MFCs

- ^ Elizabeth, Elmy (2012). "GENERATING ELECTRICITY BY "NATURE'S WAY"". SALT 'B' online magazine. 1.

- ^ Strik, David (2011). "Microbial solar cells: applying photosynthetic and electrochemically active organisms". Trends in Biotechnology. 29: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.10.001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bombelli, Paolo (2011). "Quantitative analysis of the factors limiting solar power transduction by Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in biological photovoltaic devices". Energy & Environmental Science. 4 (11): 4690–4698. doi:10.1039/c1ee02531g.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Miniature Microbial Fuel Cells". Technology Transfer Office. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Biffinger, Justin C.; Ray, Ricky; Little, Brenda; Ringeisen, Bradley R. (2007). "Diversifying Biological Fuel Cell Design by Use of Nanoporous Filters". Environmental Science and Technology. 41 (4): 1444–49.

- ^ Bennetto, H. P. (1990). "Electricity Generation by Micro-organisms" (PDF). Biotechnology Education. 1 (4): 163–168.

- ^ Cheng, Ky; Ho, G; Cord-Ruwisch, R. "Affinity of microbial fuel cell biofilm for the anodic potential". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3828–34. doi:10.1021/es8003969. ISSN 0013-936X.

- ^ Bennetto, HP.; Stirling, JL.; Tanaka, K.; Vega, CA. (Feb 1983). "Anodic reactions in microbial fuel cells". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 25 (2): 559–68. doi:10.1002/bit.260250219. PMID 18548670.

- ^ Subhas C Mukhopadhyay, Joe-Air Jiang (2013). Wireless Sensor Networks and Ecological Monitoring. Springer link. pp. 151–178. ISBN 978-3-642-36365-8.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Srikanth, S.; Sarma, P. N. (2008). "Harnessing of bioelectricity in microbial fuel cell (MFC) employing aerated cathode through anaerobic treatment of chemical wastewater using selectively enriched hydrogen producing mixed consortia" (PDF). Fuel. 87 (12): 2667–2676. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2008.03.002.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Reddy, B. P.; Saravanan, R.; Sarma, P. N. (2008). "Bioelectricity generation from chemical wastewater treatment in mediatorless (anode) microbial fuel cell (MFC) using selectively enriched hydrogen producing mixed culture under acidophilic microenvironment" (PDF). Biochemical Engineering Journal. 39: 121–130. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2007.08.023.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S., Veer Raghuvulu, S., Srikanth, S., Sarma, P.N., 2007. Bioelectricity production by meditorless microbial fuel cell (MFC) under acidophilic condition using wastewater as substrate: influence of substrate loading rate. "Current Sci." 92(12), 1720-1726.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S.; Saravanan, R.; Raghavulu, S. V.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Sarma, P. N. (2008). "Bioelectricity production from wastewater treatment in dual-chamber microbial fuel cell (MFC) using selectively enriched mixed microflora: Effect of catholyte" (PDF). Bioresource Technology. 99 (3): 596–603. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2006.12.026. PMID 17321135.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S.; Veer Raghavulu, S.; Sarma, P. N. (2008). "Biochemical evaluation of bioelectricity production process from anaerobic wastewater treatment in a single-chamber microbial fuel cell (MFC) employing glass wool membrane" (PDF). Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 23 (9): 1326–1332. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2007.11.016. PMID 18248978.

- ^ Venkata Mohan, S.; Veer Raghavulu, S.; Sarma, P. N. (2008). "Influence of anodic biofilm growth on bioelectricity production in single-chamber mediatorless microbial fuel cell using mixed anaerobic consortia" (PDF). Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 24 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2008.03.010. PMID 18440217.

- ^ Choi Y., Jung S. and Kim S. (2000) Development of Microbial Fuel Cells Using Proteus Vulgaris Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society, 21 (1), pp44–48

- ^ Chen, T.; Barton, S.C.; Binyamin, G.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, H.-H.; Heller, A. (Sep 2001). "A miniature biofuel cell". J Am Chem Soc. 123 (35): 8630–1. doi:10.1021/ja0163164. PMID 11525685.

- ^ Bullen RA, Arnot TC, Lakeman JB, Walsh FC (2006). "Biofuel cells and their development". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 21 (11): 2015–45. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.030. PMID 16569499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eos magazine, Waterstof uit het riool, June 2008

- ^ Keego Technologies - MudWatt MFC

- ^ Research-Grade BES Test Kits

- ^ Kim, BH.; Chang, IS.; Gil, GC.; Park, HS.; Kim, HJ. (April 2003). "Novel BOD (biological oxygen demand) sensor using mediator-less microbial fuel cell". Biotechnology Letters. 25 (7): 541–545. doi:10.1023/A:1022891231369. PMID 12882142.

- ^ Chang, I. S.; Moon, H.; Jang, J. K.; Kim, B. H. (2005). "Improvement of a microbial fuel cell performance as a BOD sensor using respiratory inhibitors" (PDF). Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 20 (9): 1856–1859. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2004.06.003. PMID 15681205.

- ^ Gong, Y., Radachowsky, S. E., Wolf, M., Nielsen, M. E., Girguis, P. R., & Reimers, C. E. (2011). "Benthic Microbial Fuel Cell as Direct Power Source for an Acoustic Modem and Seawater Oxygen/Temperature Sensor System". Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (11): 5047–53.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Biffinger, J.C., Little, B., Pietron, J., Ray, R., Ringeisen, B.R. (2008). "Aerobic Miniature Microbial Fuel Cells". NRL Review: 141–42.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heijne, Annemiek Ter; Liu, Fei; Weijden, Renata van der; Weijma, Jan; Buisman, Cees J.N.; Hamelers, Hubertus V.M. (2010). "Copper Recovery Combined with Electricity Production in a Microbial Fuel Cell". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (11): 4376–4381. doi:10.1021/es100526g.

- ^ Heidrick, E S; J. Dolfing; K. Scott; S. R. Edwards; C. Jones; T. P. Curtis (2013). "Production of hydrogen from domestic wastewater in a pilot-scale microbial electrolysis cell". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 97 (15): 6979–6989. doi:10.1007/s00253-012-4456-7.

- ^ Zhang, Fei, He, Zhen, Ge, Zheng (2013). "Using Microbial Fuel Cells to Treat Raw Sludge and Primary Effluent for Bioelectricity Generation". Department of Civil Engineering and Mechanics; University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Menicucci, Joseph Anthony Jr., Haluk Beyenal, Enrico Marsili, Raaja Raajan Angathevar Veluchamy, Goksel Demir, and Zbigniew Lewandowski, Sustainable Power Measurement for a Microbial Fuel Cell, AIChE Annual Meeting 2005, Cincinnati, USA

- ^ Pant, D.; Singh, A.; Van Bogaert, G.; Gallego, Y. A.; Diels, L.; Vanbroekhoven, K. (2011). "An introduction to the life cycle assessment (LCA) of bioelectrochemical systems (BES) for sustainable energy and product generation: Relevance and key aspects". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 15 (2): 1305–1313. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.10.005.

- The Biotech/Life Sciences Portal (20 Jan 2006). "Impressive idea – self-sufficient fuel cells". Baden-Württemberg GmbH. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- Liu H, Cheng S and Logan BE (2005). "Production of electricity from acetate or butyrate using a single-chamber microbial fuel cell". Environ Sci Technol. 32 (2): 658–62. doi:10.1021/es048927c.

- Rabaey, K. & W. Verstraete (2005). "Microbial fuel cells: novel biotechnology for energy generations". Trends Biotechnol. 23 (6): 291–298. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.04.008. PMID 15922081.

- Yue P.L. and Lowther K. (1986). Enzymatic Oxidation of C1 compounds in a Biochemical Fuel Cell. The Chemical Engineering Journal, 33B, p 69-77

Further reading

- Rabaey, K.; et al. (May 2007). "Microbial ecology meets electrochemistry: electricity-driven and driving communities". Isme J. 1 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.4. PMID 18043609.

- Pant, D.; et al. (March 2010). "A review of the substrates used in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) for sustainable energy production". Bioresource Technology. 101 (6): 1533–1543. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.017. PMID 19892549.

External links

- BioFuel from Microalgae

- Sustainable and efficient biohydrogen production via electrohydrogenesis -Nov 2007

- Microbial Fuel Cell blog A research-type blog on common techniques used in MFC research.

- Microbial Fuel Cells This website is originating from a few of the research groups currently active in the MFC research domain.

- Microbial Fuel Cells from Rhodopherax Ferrireducens An overview from the Science Creative Quarterly.

- Building a Two-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell

- Discussion group on Microbial Fuel Cells

- Innovation company developing MFC technology