The Great Train Robbery (1903 film): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→In popular culture: Added reference from Bojack Horseman. |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

* According to media historian [[James Chapman (media historian)|James Chapman]], the [[gun barrel sequence]] featured in the [[James Bond]] films are similar to the scene featuring of Justus D. Barnes firing at the camera. The sequence was created by [[Maurice Binder]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Chapman|first=James|title=Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films|year=2000|publisher=Columbia University Press|isbn=0-231-12048-6|page=61}}</ref> |

* According to media historian [[James Chapman (media historian)|James Chapman]], the [[gun barrel sequence]] featured in the [[James Bond]] films are similar to the scene featuring of Justus D. Barnes firing at the camera. The sequence was created by [[Maurice Binder]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Chapman|first=James|title=Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films|year=2000|publisher=Columbia University Press|isbn=0-231-12048-6|page=61}}</ref> |

||

* The final scene of [[Martin Scorsese]]'s [[Goodfellas]], in which the character Tommy shoots at the camera, recreates this film's final scene as a [[homage]]. |

* The final scene of [[Martin Scorsese]]'s [[Goodfellas]], in which the character Tommy shoots at the camera, recreates this film's final scene as a [[homage]]. |

||

* In the [[Netflix]] series [[Bojack Horseman]], Princess Carolyn has a number of conversations with Lenny Turteltaub, an old-timer in show business. As such, he regularly inserts references to meetings he had with other famous stars and filmmakers from cinema's early days, including [[Buster Keaton]] and [[Lionel Barrymore]]. During one conversation, he states: "As I said to [[Edwin S. Porter|Ed Porter]] at the premier of 'The Great Train Robbery,' 'Aggh! The train's coming right at me!'" The reference is being confused, however, with ''[[L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat]]'' by the [[Auguste and Louis Lumière|Lumière Brothers]]. The confusion comes from the fact that both ''The Great Train Robbery'' and ''L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat'' have elements that appear to be moving toward the audience (not to mention that early film audiences, according to legend, are [dubiously] purported to have ducked at these elements). However, it is in ''L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat'' that this element is a train; in ''The Great Train Robbery'' said element is the iconic [[The_Great_Train_Robbery_(1903_film)#Final_shot|final shot]] pistol being pointed at the audience and fired. |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 03:06, 18 July 2015

| The Great Train Robbery | |

|---|---|

The bandits coming under fire while attempting to escape with the loot. | |

| Directed by | Edwin S. Porter |

| Written by | Edwin S. Porter Scott Marble |

| Produced by | Edwin S. Porter |

| Starring | Alfred C. Abadie Broncho Billy Anderson Justus D. Barnes Walter Cameron |

| Cinematography | Edwin S. Porter Blair Smith |

| Edited by | Edwin S. Porter |

| Distributed by | Edison Manufacturing Company Kleine Optical Company |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Languages | Silent English intertitles |

| Budget | $150[1] |

The Great Train Robbery is a 1903 American silent short Western film written, produced, and directed by Edwin S. Porter, a former Edison Studios cameraman. Actors in the movie included Alfred C. Abadie, Broncho Billy Anderson and Justus D. Barnes, although there were no credits. Though a Western, it was filmed in Milltown, New Jersey.

At ten minutes long, The Great Train Robbery film is considered a milestone in film making, expanding on Porter's previous work Life of an American Fireman. The film used a number of unconventional techniques including composite editing, on-location shooting, and frequent camera movement. The film is one of the earliest to use the technique of cross cutting, in which two scenes are shown to be occuring simultaneously but in different locations. Some prints were also hand colored in certain scenes. Techniques used in The Great Train Robbery were inspired by those used in Frank Mottershaw's British film A Daring Daylight Burglary, released earlier in the year.[2] Film historians now largely consider The Great Train Robbery to be the first American action film and the first Western film with a "recognizable form".[3][4]

In 1990, The Great Train Robbery was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

The film opens with two bandits breaking into a railroad telegraph office, where they force the operator at gunpoint to have a train stopped and to transmit orders for the engineer orders to fill the locomotive's tender at the station's water tank. They then knock operator out and tie him up. As the train stops it is boarded by the bandits—now four. Two bandits enter an express car, kill a messenger and open a box of valuables with dynamite; the others kill the fireman and force the engineer to halt the train and disconnect the locomotive. The bandits then force the passengers off the train and rifle them for their belongings. One passenger tries to escape, but is instantly shot down. Carrying their loot, the bandits escape in the locomotive, later stopping in a valley to continue on horseback.

Back in the telegraph office, the operator awakens and tries to escape, but collapses again. His daughter enters and restores him to consciousness by dousing him with water.

Finally, at a nearby dance hall, there is some comic relief when a man is forced to dance while the bandits fire at his feet. The operator rushes into the dance hall with news of what has happened; the men grab their guns and set off in pursuit. This posse catches up with the bandits, and in a final shootout all of the bandits are killed.

Final shot

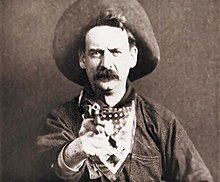

An additional scene of the film consists of a close up of the leader of the bandits, played by Justus D. Barnes, firing point blank towards the camera. While usually placed at the end, Porter stated that the scene could also be played at the beginning.

Cast

- Alfred C. Abadie as Sheriff

- Broncho Billy Anderson as Bandit / Shot Passenger / Tenderfoot Dancer

- Justus D. Barnes as Bandit Who Fires At Camera

- Walter Cameron as Sheriff

- Donald Gallaher as Little boy

- Frank Hanaway as Bandit

- Adam Charles Hayman as Bandit

- John Manus Dougherty, Sr. as Fourth bandit

- Marie Murray as Dance-hall dancer

- Mary Snow as Little girl

- George Barnes (uncredited)[5]

- Morgan Jones (uncredited)

Production notes

Porter's film was shot at the Edison studios in New York City, on location in New Jersey at the South Mountain Reservation, part of the modern Essex County Park system, as well as along the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad. Filmed during November 1903, the picture was advertised as available for sale to distributors in December of that same year.[6]

Release and reception

The Great Train Robbery had its official debut at Huber's Museum in New York City before being exhibited at eleven theaters elsewhere in the city.[7] In advertising for the film, Edison agents touted the film as "...absolutely the superior of any moving picture ever made"[8] as well as a "...faithful imitation of the genuine 'Hold Ups' made famous by various outlaw bands in the far West..."[8]

The film's budget was an estimated $150.[1] Upon its release, The Great Train Robbery became a massive success and is considered one of the first Western films.[9] It is also considered one of the first blockbusters and was one of the most popular films of the silent era until the release of The Birth of a Nation in 1915.[9]

In popular culture

- The success of The Great Train Robbery inspired several similar films including: The Bold Bank Robbery (1904) and The Hold-Up Of The Rocky Mountain Express (1906), and another Edwin S. Porter film The Life of an American Cowboy (1906).[10]

- Edwin S. Porter also made a parody of The Great Train Robbery titled The Little Train Robbery (1905), with an all-child cast in which a larger gang of bandits holds up a mini train and steal their dolls and candy.[11]

- In the 1966 Batman entitled "The Riddler's False Notion", silent film star Francis X. Bushman guest stars as the wealthy film collector who owns a print of The Great Train Robbery.[12]

- According to media historian James Chapman, the gun barrel sequence featured in the James Bond films are similar to the scene featuring of Justus D. Barnes firing at the camera. The sequence was created by Maurice Binder.[13]

- The final scene of Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas, in which the character Tommy shoots at the camera, recreates this film's final scene as a homage.

- In the Netflix series Bojack Horseman, Princess Carolyn has a number of conversations with Lenny Turteltaub, an old-timer in show business. As such, he regularly inserts references to meetings he had with other famous stars and filmmakers from cinema's early days, including Buster Keaton and Lionel Barrymore. During one conversation, he states: "As I said to Ed Porter at the premier of 'The Great Train Robbery,' 'Aggh! The train's coming right at me!'" The reference is being confused, however, with L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat by the Lumière Brothers. The confusion comes from the fact that both The Great Train Robbery and L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat have elements that appear to be moving toward the audience (not to mention that early film audiences, according to legend, are [dubiously] purported to have ducked at these elements). However, it is in L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat that this element is a train; in The Great Train Robbery said element is the iconic final shot pistol being pointed at the audience and fired.

References

- ^ a b Souter, Gerry (2012). American Shooter: A Personal History of Gun Culture in the United States. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 254. ISBN 1-597-97690-3.

- ^ Jess-Cooke, Carolyn (2009). Film Sequels: Theory and Practice from Hollywood to Bollywood. Oxford University Press. p. 1939. ISBN 0-748-68947-8.

- ^ Keim, Norman O. (2008). Our Movie Houses: A History of Film & Cinematic Innovation in Central New York. Syracuse University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-815-60896-9.

- ^ Moses, L. G. (1999). Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933. UNM Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-826-32089-9.

- ^ Bowers, Q. David (1995). "Volume 3: Biographies - Barnes, George". Thanhouser.org. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Musser, Charles (2004). "5". In Grieveson, Lee; Krämer, Peter (ed.). The Silent Cinema Reader. London: Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 0-415-25283-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ (Musser 2004, p. 90)

- ^ a b Smith, Michael Glover; Selzer, Adam (2015). Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry. Columbia University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-231-85079-4.

- ^ a b Winter, Jessica; Hughes, Lloyd (2007). The Rough Guide to Film. Penguin. p. 429. ISBN 1-405-38498-0.

- ^ Lusted, David (2014). The Western. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 1-317-87491-9.

- ^ "Overview of Edison Motion Pictures by Genre - Drama & Adventure". Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- ^ Eisner, Joel; Krinsky, David (1984). Television Comedy Series: An Episode Guide To 153 TV Sitcoms In Syndication. McFarland. p. 93. ISBN 0-899-50088-9.

- ^ Chapman, James (2000). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. Columbia University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-231-12048-6.

External links

- The Great Train Robbery on YouTube

- Download from the Library of Congress (in MPEG-1, RealVideo or QuickTime format)

- The Great Train Robbery at IMDb

- The short film The Great Train Robbery is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The Great Train Robbery at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Train Robbery at AllMovie

- Great Films: The Great Train Robbery

- 1903 films

- 1900s action films

- 1900s Western (genre) films

- American action films

- American films

- American silent short films

- American Western (genre) films

- Black-and-white films

- Films about hijackings

- Films based on plays

- Films directed by Edwin S. Porter

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Rail transport films

- Heist films

- Thomas Edison

- United States National Film Registry films