The unexamined life is not worth living: Difference between revisions

Whalestate (talk | contribs) |

Undid revision 697067192 by Whalestate (talk) -- removing the 'surveillance camera' picture and its caption, as it seems out of place in this article. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Surveillance Camera over the Platform of Train.jpg|thumb|Surveillance Camera over the Platform of Train]] |

|||

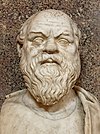

'''The unexamined life is not worth living''' ({{lang-grc|ὁ ... ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ}}) is a famous dictum apparently uttered by [[Socrates]] at [[Trial of Socrates|his trial]] for [[impiety]] and corrupting youth, for which he was subsequently sentenced to death, as described in Plato's ''[[Apology (Plato)|Apology]]''. |

'''The unexamined life is not worth living''' ({{lang-grc|ὁ ... ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ}}) is a famous dictum apparently uttered by [[Socrates]] at [[Trial of Socrates|his trial]] for [[impiety]] and corrupting youth, for which he was subsequently sentenced to death, as described in Plato's ''[[Apology (Plato)|Apology]]''. |

||

Revision as of 18:52, 2 January 2016

The unexamined life is not worth living (Ancient Greek: ὁ ... ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ) is a famous dictum apparently uttered by Socrates at his trial for impiety and corrupting youth, for which he was subsequently sentenced to death, as described in Plato's Apology.

Rationale

This statement relates to Socrates' understanding and attitude towards death and his commitment to fulfill his goal of investigating and understanding the statement of the Pythia. Socrates understood the Pythia's response to Chaerephon's question as a communication from the god Apollo and this became Socrates's prime directive, his raison d'etre. For Socrates, to be separated from elenchus by exile (preventing him from investigating the statement) was therefore a fate worse than death. Since Socrates was religious and trusted his religious experiences, such as his guiding daimonic voice, he accordingly preferred to continue to seek the true answer to his question, in the after-life, than live a life not identifying the answer on earth.[1]

Meaning

The words were supposedly spoken by Socrates at his trial after he chose death rather than exile. They represent (in modern terms) the noble choice, that is, the choice of death in the face of an alternative.[2]

Interpretation

To the notion of the love of knowing, falls to the mind one certain individual, Socrates, who exemplifies more than anyone in history (for some) the pursuit through questioning and logical argument, acquisition of knowledge, over all and everything, to gain knowledge at his discretion, by examining and by thinking. Whose examination of life spilled out into the lives of others in his society, and became an inquiry into lives of those others in addition to his own life, which he subsequently lost.[3][4]

References

- ^ Brickhouse, Thomas C.; Smith, Nicholas D. (1994). Plato's Socrates. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-0-19-510111-9.

- ^ Julian Baggini - Wisdom's folly The Guardian newspaper (Guardian News and Media Limited) Thursday 12 May 2005 [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

- ^ Spivey, Nigel; Squire, Michael (1 March 2011). Panorama of the Classical World. Getty Publications. pp. 230–. ISBN 978-1-60606-056-8.

- ^ D.M. Johnson - Socrates and Athens (p.74) Cambridge University Press, 31 Mar 2011 ISBN 0521757487 [Retrieved 2015-04-25]

External links

- Plato. Apology 38a. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler; Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966. via Perseus Tufts

- J. O. Famakinwa - IS THE UNEXAMINED LIFE WORTH LIVING OR NOT? Think / Volume 11 / Issue 31 / Summer 2012, pp 97–103 The Royal Institute of Philosophy 2012

- J. M. Ambury - Socrates (469—399 B.C.E.) -2biii - The Unexamined Life in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy