Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Currently, there are works relating to the use of skeletal rearrangement in the synthesis of bridged azaheterocycles. These data are summarized in <ref>{{cite journal|author=Zubkov, F. I. ; Zaytsev, V. P.; Nikitina, E. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Gozun, S. V.; Boltukhina, E. V.; Varlamov, A. V.|doi=10.1016/j.tet.2011.09.099|title=Skeletal Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of perhydro-3a,6;4,5-diepoxyisoindoles|year=2011|journal=Tetrahedron|volume=67|issue=47|pages=9148}}</ref> |

Currently, there are works relating to the use of skeletal rearrangement in the synthesis of bridged azaheterocycles. These data are summarized in <ref>{{cite journal|author=Zubkov, F. I. ; Zaytsev, V. P.; Nikitina, E. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Gozun, S. V.; Boltukhina, E. V.; Varlamov, A. V.|doi=10.1016/j.tet.2011.09.099|title=Skeletal Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of perhydro-3a,6;4,5-diepoxyisoindoles|year=2011|journal=Tetrahedron|volume=67|issue=47|pages=9148}}</ref> |

||

:[[File: |

:[[File:Wagner-Meerwein heterocyclic.svg|Some examples of Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement in heterocyclic series|950px]] |

||

Plausible mechanisms of the Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of diepoxyisoindoles: |

Plausible mechanisms of the Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of diepoxyisoindoles: |

||

Revision as of 16:23, 11 April 2016

A Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement is a class of carbocation 1,2-rearrangement reactions in which a hydrogen, alkyl or aryl group migrates from one carbon to a neighboring carbon.[1][2]

Several reviews have been published.[3][4][5][6][7]

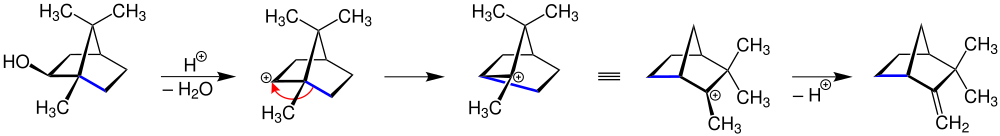

The rearrangement was first discovered in bicyclic terpenes for example the conversion of isoborneol to camphene:[8]

The story of the rearrangement reveals that many scientists were puzzled with this and related reactions and its close relationship to the discovery of carbocations as intermediates.[9]

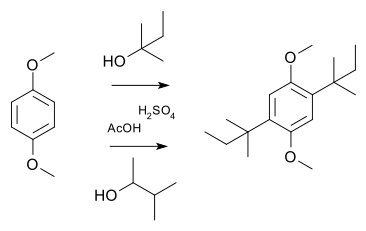

In a simple demonstration reaction of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene with either 2-methyl-2-butanol or 3-methyl-2-butanol in sulfuric acid and acetic acid yields the same disubstituted product,[10] the latter via a hydride shift of the cationic intermediate:

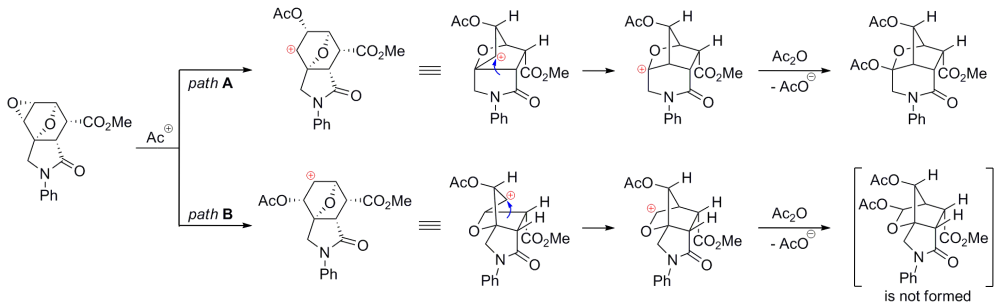

Currently, there are works relating to the use of skeletal rearrangement in the synthesis of bridged azaheterocycles. These data are summarized in [11]

Plausible mechanisms of the Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of diepoxyisoindoles:

The related Nametkin rearrangement named after Sergey Namyotkin involves the rearrangement of methyl groups in certain terpenes. In some cases the reaction type is also called a retropinacol rearrangement (see Pinacol rearrangement).

See also

References

- ^ Wagner, G. (1899). J. Russ. Phys. Chem. Soc. 31: 690.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Hans Meerwein (1914). "Über den Reaktionsmechanismus der Umwandlung von Borneol in Camphen; [Dritte Mitteilung über Pinakolinumlagerungen.]". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. 405 (2): 129–175. doi:10.1002/jlac.19144050202.

- ^ Popp, F. D.; McEwen, W. E. (1958). "Polyphosphoric Acids As a Reagent in Organic Chemistry". Chem. Rev. 58 (2): 375. doi:10.1021/cr50020a004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cargill, Robert L.; Jackson, Thomas E.; Peet, Norton P.; Pond, David M. (1974). "Acid-catalyzed rearrangements of β,γ-unsaturated ketones". Acc. Chem. Res. 7: 106–113. doi:10.1021/ar50076a002.

- ^ Olah, G. A. (1976). "Stable carbocations, 189. The σ-bridged 2-norbornyl cation and its significance to chemistry". Acc. Chem. Res. 9 (2): 41. doi:10.1021/ar50098a001.

- ^ Hogeveen, H.; Van Krutchten, E. M. G. A. (1979). "Wagner-meerwein rearrangements in long-lived polymethyl substituted bicyclo[3.2.0]heptadienyl cations". Top. Curr. Chem. Topics in Current Chemistry. 80: 89–124. doi:10.1007/BFb0050203. ISBN 3-540-09309-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hanson, J. R. (1991). "Wagner–Meerwein Rearrangements". Comp. Org. Syn. 3: 705–719. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00077-9. ISBN 978-0-08-052349-1.

- ^ March, Jerry (1985), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure, 3rd edition, New York: Wiley, ISBN 9780471854722, OCLC 642506595

- ^ Birladeanu, L. (2000). "The Story of the Wagner-Meerwein Rearrangement". J. Chem. Ed. 77 (7): 858–863. doi:10.1021/ed077p858.

- ^ Polito, Victoria; Hamann, Christian S.; Rhile, Ian J. (2010). "Carbocation Rearrangement in an Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Discovery Laboratory". Journal of Chemical Education. 87 (9): 969. doi:10.1021/ed9000238.

- ^ Zubkov, F. I. ; Zaytsev, V. P.; Nikitina, E. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Gozun, S. V.; Boltukhina, E. V.; Varlamov, A. V. (2011). "Skeletal Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement of perhydro-3a,6;4,5-diepoxyisoindoles". Tetrahedron. 67 (47): 9148. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.09.099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)