Paxton Boys: Difference between revisions

Rchard2scout (talk | contribs) →Sources: Remove redundant ISBNs |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Following attacks on the Conestoga, in January 1764 about 250 Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia to present their grievances to the legislature. Met by leaders in Germantown, they agreed to disperse on the promise by [[Benjamin Franklin]] that their issues would be considered. |

Following attacks on the Conestoga, in January 1764 about 250 Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia to present their grievances to the legislature. Met by leaders in Germantown, they agreed to disperse on the promise by [[Benjamin Franklin]] that their issues would be considered. |

||

I like like squirrels |

|||

==Attack on Susquehannock== |

==Attack on Susquehannock== |

||

Revision as of 16:23, 14 September 2017

The Paxton Boys were frontiersmen of Scots-Irish origin from along the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania who formed a vigilante group to retaliate in 1763 against local American Indians in the aftermath of the French and Indian War and Pontiac's Rebellion. They are widely known for murdering 21 Susquehannock in events collectively called the Conestoga Massacre.

Following attacks on the Conestoga, in January 1764 about 250 Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia to present their grievances to the legislature. Met by leaders in Germantown, they agreed to disperse on the promise by Benjamin Franklin that their issues would be considered. I like like squirrels

Attack on Susquehannock

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War, the frontier of Pennsylvania remained unsettled. A new wave of Scots-Irish immigrants encroached on Native American land in the backcountry often in blatant violation of previously signed treaties. These settlers claimed that Indians often raided their homes, killing men, women and children. Reverend John Elder, who was the parson at Paxtang, became a leader of the settlers. He was known as the "Fighting Parson" and kept his rifle in the pulpit while he delivered his sermons.[1] Elder helped organize the settlers into a mounted militia and was named Captain of the group, known as the "Pextony boys."[2]

Although there had been no Indian attacks in the area, the Paxton Boys claimed that the Conestoga secretly provided aid and intelligence to the hostiles. At daybreak on December 14, 1763, a vigilante group of the Scots-Irish frontiersmen attacked Conestoga homes at Conestoga Town (near present-day Millersville), murdered six, and burned their cabins.

The Susquehannock tribe had lived on the land which was ceded by William Penn to their ancestors in the 1690s. Many Conestoga were Christian, and they had lived peacefully with their European neighbors for decades. They lived by bartering handicrafts, hunting, and from subsistence food given them by the Pennsylvania government. Because of a snowstorm, most of the Conestogas had been unable to reach home the previous evening and spent the night with neighbors. Those at the camp were scalped, or otherwise mutilated, and their huts were set on fire. Most of the camp burned down.[3]

The colonial government held an inquest and determined that the killings were murder. The new governor, John Penn offered a reward for capture of the Paxton Boys. Penn placed the remaining sixteen Conestoga in protective custody in Lancaster but the Paxton Boys broke in on December 27, 1763. They killed, scalped and dismembered six adults and eight children. The government of Pennsylvania offered a new reward after this second attack, this time $600, for the capture of anyone involved. The attackers were never identified.

I saw a number of people running down the street towards the gaol, which enticed me and other lads to follow them. At about sixty or eighty yards from the gaol, we met from twenty-five to thirty men, well mounted on horses, and with rifles, tomahawks, and scalping knives, equipped for murder. I ran into the prison yard, and there, O what a horrid sight presented itself to my view!- Near the back door of the prison, lay an old Indian and his women, particularly well known and esteemed by the people of the town, on account of his placid and friendly conduct. His name was Will Sock; across him and his Native women lay two children, of about the age of three years, whose heads were split with the tomahawk, and their scalps all taken off. Towards the middle of the gaol yard, along the west side of the wall, lay a stout Indian, whom I particularly noticed to have been shot in the breast, his legs were chopped with the tomahawk, his hands cut off, and finally a rifle ball discharged in his mouth; so that his head was blown to atoms, and the brains were splashed against, and yet hanging to the wall, for three or four feet around. This man’s hands and feet had also been chopped off with a tomahawk. In this manner lay the whole of them, men, women and children, spread about the prison yard: shot-scalped-hacked-and cut to pieces. - William Henry of Lancaster[4]

The Rev. Elder, who was not directly implicated in either attack, wrote to Governor Penn, on January 27, 1764:

The storm which had been so long gathering, has, at length, exploded. Had Government removed the Indians, which had been frequently, but without effect, urged, this painful catastrophe might have been avoided. What could I do with men heated to madness? All that I could do was done. I expostulated; but life and reason were set at defiance. Yet the men in private life are virtuous and respectable; not cruel, but mild and merciful. The time will arrive when each palliating circumstance will be weighed. This deed, magnified into the blackest of crimes, shall be considered as one of those ebullitions of wrath, caused by momentary excitement, to which human infirmity is subjected.[2]

March on Philadelphia

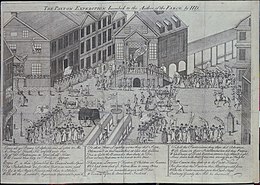

In January 1764, the Paxton Boys marched toward Philadelphia with about 250 men to challenge the government for failing to protect them. Benjamin Franklin led a group of civic leaders to meet them in Germantown, then a separate settlement northwest of the city, and hear their grievances. After the leaders agreed to read the men's pamphlet of issues before the colonial legislature, the mob agreed to disperse.

Many colonists were outraged about the December killings of innocent Conestoga, describing the murders as more savage than those committed by Indians. Benjamin Franklin's "Narrative of the Late Massacres" concluded with noting that the Conestoga would have been safe among any other people on earth, no matter how primitive, except "'white savages' from Peckstang and Donegall!"[5]

Lazarus Stewart, a former leader of the Paxton Boys, was killed by Iroquois warriors in the Wyoming Massacre in 1778 during the American Revolutionary War.[6] In the Wyoming Valley event, one of three famous massacres during many scattered Tory-Amerindian staged attacks on colonial settlements that year in Connecticut, New York and Pennsylvania, Mohawk chief Joseph Brant led a group of Loyalists, Mohawk and other warriors against rebel colonial settlers in the area along the North Branch Susquehanna River. The raids resulted in the Sullivan Expedition the next year which effectively broke the power of the Six Nations of the Iroquois below Canada; and forced the British Colonial powers in Canada to shelter the Amerindians they'd incited into the attacks.

In fiction

Each of these novels references the Paxton Boys:

- The Light in the Forest (1953), by Conrad Richter.

- Mason & Dixon (1997) by Thomas Pynchon, includes the Lancaster Massacre.

- Robert J. Shade. Conestoga Winter: A Story of Border Vengeance (Forbes Road) (volume 2; 2013) includes the Lancaster Massacre.

- Mindy Starns Clark and Leslie Gould. The Amish Seamstress (2013); the narrator finds out quite a bit about Amish involvement in the events of the time.

See also

- Paxtang

- Black Boys

- Enoch Brown School Massacre (July 26, 1764)

- List of unsolved deaths

Sources

- Brubaker, John H. (2010). Massacre of the Conestogas: On the Trail of the Paxton Boys in Lancaster County. History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-061-4.

- Griffin, Patrick (2008). American Leviathan: Empire, Nation, and Revolutionary Frontier (Chapter 2). Macmillan. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-8090-2491-9.

- Kenny, Kevin (2009). Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn's Holy Experiment. Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-533150-9.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 724. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

- Silver, Peter (2009). Our Savage Neighbors, How Indian War Transformed Early America. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-393-33490-6.

- Taylor, Alan, American Colonies, New York: Viking Press, 2001.

References

- ^ McAlarney, Mathias Wilson (1890). History of the sesqui-centennial of Paxtang church: September 18, 1890. Harrisburg Publishing Company. p. 224.

- ^ a b Sprague, William Buell (1858). Annals of the American Pulpit: Presbyterian. 1859. Robert Carter & Brothers. pp. 77–79.

- ^ Brubaker, John H. (2010). Massacre of the Conestogas: On the Trail of the Paxton Boys in Lancaster County. History Press. pp. 23–24.

- ^ quoted in Jeremy Engels, "Equipped for Murder: The Paxton Boys and The Spirit of Killing All Indians in Pennsylvania, 1763-1764," Rhetoric & Public Affairs, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2005, pp. 355-382; ISSN 1094-8392

- ^ Silver, Peter. Our Savage Neighbors, p. 203

- ^ Bradsby, Henry C. (1893). History of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: Nelson. p. 1.567. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

External links

- Digital Paxton, An Introduction to the 1764 Pamphlet Wars, Will Fenton

- "A Narrative of the Late Massacres...", Benjamin Franklin's account of the massacre and criticism of the Paxton Boys

- Egle, William Henry (1890). Glimpses of the history of old Paxtang Church. Harrisburg Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paxton Boys US History.com