SN 1987A: Difference between revisions

Adding a section dealing with the discovery of the condensation of warm dust in the ejecta |

|||

| Line 533: | Line 533: | ||

|bibcode=2018SciA....4O1054L |

|bibcode=2018SciA....4O1054L |

||

|doi=10.1126/sciadv.aao1054 |

|doi=10.1126/sciadv.aao1054 |

||

}}</ref>, that was the first time that such a condensation was observed. If SN 1987A is a typical representative of its class then the derived mass of the warm dust formed in the debris of Core Collapse supernovae is not sufficient to account for all the dust observed in the early universe. However, a much larger reservoir of ~0.25 solar mass of colder dust (at ~26 K) in the ejecta of SN 1987A was found with the Hershel infrared telescope in 2011 and confirmed by ALMA later on (2014)(see below). That discovery changed the story! |

}}</ref>, that was the first time that such a condensation was observed. If SN 1987A is a typical representative of its class then the derived mass of the warm dust formed in the debris of Core Collapse supernovae is not sufficient to account for all the dust observed in the early universe. However, a much larger reservoir of ~0.25 solar mass of colder dust (at ~26 K) in the ejecta of SN 1987A was found with the Hershel infrared space telescope in 2011 and confirmed by ALMA later on (2014)(see below). That discovery changed the story! |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{Portal|Star}} |

{{Portal|Star}} |

||

Revision as of 18:47, 8 April 2018

| |

| Event type | Supernova |

|---|---|

| Type II (peculiar)[2] | |

| Date | February 24, 1987 (23:00 UTC) Las Campanas Observatory[3] |

| Constellation | Dorado |

| Right ascension | 05h 35m 28.03s[4] |

| Declination | −69° 16′ 11.79″[4] |

| Epoch | J2000 |

| Galactic coordinates | G279.7-31.9 |

| Distance | 51.4 kpc (168,000 ly)[4] |

| Host | Large Magellanic Cloud |

| Progenitor | Sanduleak -69° 202 |

| Progenitor type | B3 supergiant |

| Colour (B-V) | +0.085 |

| Notable features | Closest recorded supernova since invention of telescope |

| Peak apparent magnitude | +2.9 |

| Other designations | SN 1987A, AAVSO 0534-69, INTREF 262, SNR 1987A, SNR B0535-69.3, [BMD2010] SNR J0535.5-6916 |

| | |

SN 1987A was a peculiar type II supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy satellite of the Milky Way. It occurred approximately 51.4 kiloparsecs (168,000 ly) from Earth. It was the closest observed supernova since SN 1604, which occurred in the Milky Way itself, and close enough to be easily visible to the naked eye

The light from the supernova reached Earth on February 23, 1987.[5] As the first supernova discovered in 1987, it was labeled "1987A". Its brightness peaked in May, with an apparent magnitude of about 3, and slowly declined in the following months. It was the first opportunity for modern astronomers to study the development of a supernova in great detail, and its observations have provided much insight into core-collapse supernovae.

SN 1987A provided the first chance to confirm by direct observation the radioactive source of the energy for visible light emissions, by detecting predicted gamma-ray line radiation from two of its abundant radioactive nuclei. This proved the radioactive nature of the long-duration post-explosion glow of supernovae.

Discovery

SN 1987A was discovered independently by Ian Shelton and Oscar Duhalde at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile on February 24, 1987, and within the same 24 hours by Albert Jones in New Zealand.[3] On March 4–12, 1987, it was observed from space by Astron, the largest ultraviolet space telescope of that time.[6]

Progenitor

Four days after the event was recorded, the progenitor star was tentatively identified as Sanduleak −69° 202, a blue supergiant.[8] After the supernova faded, that identification was definitely confirmed by Sanduleak −69° 202 having disappeared. This was an unexpected identification, because models of high mass stellar evolution at the time did not predict that blue supergiants are susceptible to a supernova event.

Some models of the progenitor attributed the color to its chemical composition rather than its evolutionary state, particularly the low levels of heavy elements, among other factors.[9] There was some speculation that the star might have merged with a companion star before the supernova.[10] However, it is now widely understood that blue supergiants are natural progenitors of some supernovae, although there is still speculation that the evolution of such stars could require mass loss involving a binary companion.[11]

Neutrino emissions

Approximately two to three hours before the visible light from SN 1987A reached Earth, a burst of neutrinos was observed at three neutrino observatories. This is likely due to neutrino emission, which occurs simultaneously with core collapse, but before visible light was emitted. Visible light is transmitted only after the shock wave reaches the stellar surface.[12] At 07:35 UT, Kamiokande II detected 12 antineutrinos; IMB, 8 antineutrinos; and Baksan, 5 antineutrinos; in a burst lasting less than 13 seconds. Approximately three hours earlier, the Mont Blanc liquid scintillator detected a five-neutrino burst, but this is generally not believed to be associated with SN 1987A.[9]

The Kamiokande II detection, which at 12 neutrinos had the largest sample population, showed that the neutrinos arrived in two distinct pulses. The first pulse, which started at 07:35:35 comprised 9 neutrinos, all of which arrived over a period of 1.915 seconds. A second pulse of three neutrinos arrived between 9.219 and 12.439 seconds after the first neutrino was detected, for a pulse duration of 3.220 seconds.

Although only 25 neutrinos were detected during the event, it was a significant increase from the previously observed background level. This was the first time neutrinos known to be emitted from a supernova had been observed directly, which marked the beginning of neutrino astronomy. The observations were consistent with theoretical supernova models in which 99% of the energy of the collapse is radiated away in the form of neutrinos.[13] The observations are also consistent with the models' estimates of a total neutrino count of 1058 with a total energy of 1046 joules.[14]

The neutrino measurements allowed upper bounds on neutrino mass and charge, as well as the number of flavors of neutrinos and other properties.[9] For example, the data show that within 5% confidence, the rest mass of the electron neutrino is at most 16 eV/c2, 1/30,000 the mass of an electron. The data suggest that the total number of neutrino flavors is at most 8 but other observations and experiments give tighter estimates. Many of these results have since been confirmed or tightened by other neutrino experiments such as more careful analysis of solar neutrinos and atmospheric neutrinos as well as experiments with artificial neutrino sources.[citation needed]

Missing neutron star

SN 1987A appears to be a core-collapse supernova, which should result in a neutron star given the size of the original star.[9] The neutrino data indicate that a compact object did form at the star's core. However, since the supernova first became visible, astronomers have been searching for the collapsed core but have not detected it. The Hubble Space Telescope has taken images of the supernova regularly since August 1990, but, so far, the images have shown no evidence of a neutron star. A number of possibilities for the 'missing' neutron star are being considered, although none are clearly favored. The first is that the neutron star is enshrouded in dense dust clouds so that it cannot be seen. Another is that a pulsar was formed, but with either an unusually large or small magnetic field. It is also possible that large amounts of material fell back on the neutron star, so that it further collapsed into a black hole. Neutron stars and black holes often give off light when material falls onto them. If there is a compact object in the supernova remnant, but no material to fall onto it, it would be very dim and could therefore avoid detection. Other scenarios have also been considered, such as if the collapsed core became a quark star.[16][17]

Light curve

Much of the light curve, or graph of luminosity as a function of time, after the explosion of a Type II Supernova such as SN 1987A is provided its energy by radioactive decay. Although the luminous emission consists of optical photons, it is the radioactive power absorbed that keeps the remnant hot enough to radiate light. Without radioactive heat it would quickly dim. The radioactive decay of 56Ni through its daughters 56Co to 56Fe produces gamma-ray photons that are absorbed and dominate the heating and thus the luminosity of the ejecta at intermediate times (several weeks) to late times (several months).[18] Energy for the peak of the light curve of SN1987A was provided by the decay of 56Ni to 56Co (half life 6 days) while energy for the later light curve in particular fit very closely with the 77.3 day half-life of 56Co decaying to 56Fe. Later measurements by space gamma-ray telescopes of the small fraction of the 56Co and 57Co gamma rays that escaped the SN1987A remnant without absorption[19][20] confirmed earlier predictions that those two radioactive nuclei were the power source.[21]

Because the 56Co in SN1987A has now completely decayed, it no longer supports the luminosity of the SN 1987A ejecta. That is currently powered by the radioactive decay of 44Ti with a half life of about 60 years. With this change, X-rays produced by the ring interactions of the ejecta began to contribute significantly to the total light curve. This was noticed by the Hubble Space Telescope as a steady increase in luminosity 10,000 days after the event in the blue and red spectral bands.[22] X-ray lines 44Ti observed by the INTEGRAL space X-ray telescope showed that the total mass of radioactive 44Ti synthesized during the explosion was 3.1 ± 0.8×10−4 M☉.[23]

Observations of the radioactive power from their decays in the 1987A light curve have measured accurate total masses of the 56Ni, 57Ni, and 44Ti created in the explosion, which agree with the masses measured by gamma-ray line space telescopes and provides nucleosynthesis constraints on the computed supernova model.[24]

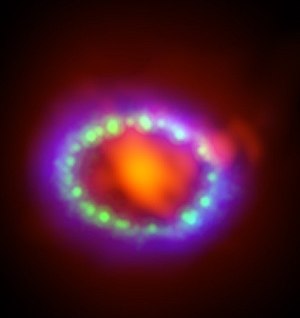

Interaction with circumstellar material

The three bright rings around SN 1987A that were visible after a few months in images by the Hubble Space Telescope are material from the stellar wind of the progenitor. These rings were ionized by the ultraviolet flash from the supernova explosion, and consequently began emitting in various emission lines. These rings did not "turn on" until several months after the supernova; the turn-on process can be very accurately studied through spectroscopy. The rings are large enough that their angular size can be measured accurately: the inner ring is 0.808 arcseconds in radius. The time light traveled to light up the inner ring gives its radius of 0.66 (ly) light years. Using this as the base of a right angle triangle and the angular size as seen from the Earth for the local angle, one can use basic trigonometry to calculate the distance to SN 1987A, which is about 168,000 light-years.[26] The material from the explosion is catching up with the material expelled during both its red and blue supergiant phases and heating it, so we observe ring structures about the star.

Around 2001, the expanding (>7000 km/s) supernova ejecta collided with the inner ring. This caused its heating and the generation of x-rays — the x-ray flux from the ring increased by a factor of three between 2001 and 2009. A part of the x-ray radiation, which is absorbed by the dense ejecta close to the center, is responsible for a comparable increase in the optical flux from the supernova remnant in 2001–2009. This increase of the brightness of the remnant reversed the trend observed before 2001, when the optical flux was decreasing due to the decaying of 44Ti isotope.[25]

A study reported in June 2015,[27] using images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope taken between 1994 and 2014, shows that the emissions from the clumps of matter making up the rings are fading as the clumps are destroyed by the shock wave. It is predicted the ring will fade away between 2020 and 2030. As the shock wave passes the circumstellar ring it will trace the history of mass loss of the supernova's progenitor and provide useful information for discriminating among various models for the progenitor of SN 1987A.[28]

Condensation of Warm Dust in the Ejecta

Soon after the SN 1987A outburst, three major groups embarked in a photometric monitoring of the supernova (SAAO [29]

[30]

, CTIO [31]

Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

, and ESO [32]

[33].

In particular, the ESO team reported an infrared excess which became apparent beginning less than one month after the explosion (March 11, 1987). They discussed possible interpretations for it: while they rejected the infrared echo hypothesis, they claimed that thermal emission from dust could have condensed in the ejecta, (in which case they estimated the temperature was ~ 1250 K, and the dust mass was Md ~ 6.6 E-07 Msol). These authors showed that it was unlikely that the IR excess could be produced by optically thick free-free emission, because the luminosity in UV photons needed to keep the envelope ionized was much larger than what was available. They didn’t rule out this possibility however, in view of the eventuality of electron scattering, which these authors had not considered.

However, none of these three groups had sufficiently convincing proofs to claim for a dusty ejecta on the basis of an IR excess alone.

An independent Australian team[34] advanced several argument in favor of an echo interpretation. This seemingly straightforward interpretation of the nature of the IR emission was challenged by the ESO group[35]

and definitively ruled out after presenting optical evidence for the presence of dust in the SN ejecta[36]. To discriminate between the two interpretations, [37]considered the implication of the presence of an echoing dust cloud on the optical light curve, and on the existence of diffuse optical emission around the SN. They concluded that the expected optical echo from the cloud should be resolvable, and could be very bright with an integrated visual brightness of 10.3 mag around day 650. However, further optical observations, as expressed in SN light curve, showed no inflection in the light curve at the predicted level. Finally, the ESO team presented a convincing clumpy model for dust condensation in the ejecta[38]

[39] and should be credited for the discovery.

Although it had been thought more than 50 years ago that dust could form in the ejecta of a core-collapse supernova[40] , in particular to explain the origin of dust seen in far galaxies[41], that was the first time that such a condensation was observed. If SN 1987A is a typical representative of its class then the derived mass of the warm dust formed in the debris of Core Collapse supernovae is not sufficient to account for all the dust observed in the early universe. However, a much larger reservoir of ~0.25 solar mass of colder dust (at ~26 K) in the ejecta of SN 1987A was found with the Hershel infrared space telescope in 2011 and confirmed by ALMA later on (2014)(see below). That discovery changed the story!

See also

- History of supernova observation

- List of supernovae

- List of supernova remnants

- List of supernova candidates

References

- ^

"ALMA Spots Supernova Dust Factory". European Southern Observatory. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lyman, J. D.; Bersier, D.; James, P. A. (2013). "Bolometric corrections for optical light curves of core-collapse supernovae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 437 (4): 3848. arXiv:1311.1946. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437.3848L. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt2187.

- ^ a b "IAUC4316: 1987A, N. Cen. 1986". February 24, 1987. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c

"SN1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud". Hubble Heritage Project. Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ West, R. M.; Lauberts, A.; Schuster, H.-E.; Jorgensen, H. E. (1987). "Astrometry of SN 1987A and Sanduleak-69 202". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 177 (1–2): L1–L3. Bibcode:1987A&A...177L...1W.

- ^ Boyarchuk, A. A.; et al. (1987). "Observations on Astron: Supernova 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud". Pis'ma v Astronomicheskii Zhurnal (in Russian). 13: 739–743. Bibcode:1987PAZh...13..739B.

- ^

"Hubble Revisits an Old Friend". Picture of the Week. European Space Agency/Hubble. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sonneborn, G. (1987). "The Progenitor of SN1987A". In Kafatos, M.; Michalitsianos, A. (eds.). Supernova 1987a in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35575-3.

- ^ a b c d Arnett, W. D.; Bahcall, J. N.; Kirshner, R. P.; Woosley, S. E. (1989). "Supernova 1987A". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 27: 629–700. Bibcode:1989ARA&A..27..629A. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.27.090189.003213.

- ^ Podsiadlowski, P. (1992). "The progenitor of SN 1987 A". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 104 (679): 717. Bibcode:1992PASP..104..717P. doi:10.1086/133043.

- ^ Dwarkadas, V. V. (2011). "On luminous blue variables as the progenitors of core-collapse supernovae, especially Type IIn supernovae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 412 (3): 1639–1649. arXiv:1011.3484. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.412.1639D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.18001.x.

- ^ Nomoto, K.; Shigeyama, T. "Supernova 1987A: Constraints on the Theoretical Model". In Kafatos, M.; Michalitsianos, A. (eds.). Supernova 1987a in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Cambridge University Press. § 3.2. ISBN 0-521-35575-3.

- ^ Scholberg, K. (2012). "Supernova Neutrino Detection". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 62: 81–103. arXiv:1205.6003. Bibcode:2012ARNPS..62...81S. doi:10.1146/annurev-nucl-102711-095006.

- ^ Pagliaroli, G.; Vissani, F.; Costantini, M. L.; Ianni, A. (2009). "Improved analysis of SN1987A antineutrino events". Astroparticle Physics. 31 (3): 163. arXiv:0810.0466. Bibcode:2009APh....31..163P. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2008.12.010.

- ^

"New image of SN 1987A". European Space Agency/Hubble. February 24, 2017. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chan, T. C.; et al. (2009). "Could the compact remnant of SN 1987A be a quark star?". The Astrophysical Journal. 695: 732. arXiv:0902.0653. Bibcode:2009ApJ...695..732C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/1/732.

- ^

Parsons, P. (February 21, 2009). "Quark star may hold secret to early universe". New Scientist. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kasen, D.; Woosley, S. (2009). "Type II Supernovae: Model Light Curves and Standard Candle Relationships". The Astrophysical Journal. 703 (2): 2205–2216. arXiv:0910.1590. Bibcode:2009ApJ...703.2205K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/703/2/2205.

- ^ Matz, S. M.; et al. (1988). "Gamma-ray line emission from SN1987A". Nature. 331 (6155): 416–418. Bibcode:1988Natur.331..416M. doi:10.1038/331416a0.

- ^ Kurfess, J. D.; et al. (1992). "Oriented Scintillation Spectrometer Experiment observations of Co-57 in SN 1987A". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 399 (2): L137–L140. Bibcode:1992ApJ...399L.137K. doi:10.1086/186626.

- ^ Clayton, D. D.; Colgate, S. A.; Fishman, G. J. (1969). "Gamma-Ray Lines from Young Supernova Remnants". The Astrophysical Journal. 155: 75. Bibcode:1969ApJ...155...75C. doi:10.1086/149849.

- ^ McCray, R.; Fansson, C. (2016). "The Remnant of Supernova 1987A". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 54: 19–52. Bibcode:2016ARA&A..54...19M. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082615-105405.

- ^ Grebenev, S. A.; Lutovinov, A. A.; Tsygankov, S. S.; Winkler, C. (2012). "Hard-X-ray emission lines from the decay of 44Ti in the remnant of supernova 1987A". Nature. 490 (7420): 373–375. arXiv:1211.2656. Bibcode:2012Natur.490..373G. doi:10.1038/nature11473. PMID 23075986.

- ^ Fransson, C.; et al. (2007). "Twenty Years of Supernova 1987A". The Messenger. 127: 44. Bibcode:2007Msngr.127...44F.

- ^ a b Larsson, J.; et al. (2011). "X-ray illumination of the ejecta of supernova 1987A". Nature. 474 (7352): 484–486. arXiv:1106.2300. Bibcode:2011Natur.474..484L. doi:10.1038/nature10090. PMID 21654749.

- ^ Panagia, N. (1998). "New Distance Determination to the LMC". Memorie della Societa Astronomia Italiana. 69: 225. Bibcode:1998MmSAI..69..225P.

- ^

Kruesi, L. "Supernova prized by astronomers begins to fade from view". New Scientist. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fransson, C.; et al. (2015). "The Destruction of the Circumstellar Ring of SN 1987A". The Astrophysical Journal. 806: L19. arXiv:1505.06669. Bibcode:2015ApJ...806L..19F. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/806/1/L19.

- ^ Menzies, J.W.; et al. (1987). "Spectroscopic and photometric observations of SN 1987a - The first 50 days". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 227: 39. Bibcode:1987MNRAS.227P..39M. doi:10.1093/mnras/227.1.39P.

- ^ Catchpole, R.M.; et al. (1987). "Spectroscopic and photometric observations of SN 1987a. II - Days 51 to 134". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 229: 15. Bibcode:1987MNRAS.229P..15C. doi:10.1093/mnras/229.1.15P.

- ^ Elias, J.H.; et al. (1988). "Line identifications in the infrared spectrum of SN 1987A". The Astrophysical Journal. 331: L9. Bibcode:1988ApJ...331L...9E. doi:10.1086/185225.

- ^ Bouchet, P.; et al. (1987). "Infrared photometry of SN 1987A". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 177: L9. Bibcode:1987A&A...177L...9B.

- ^

Bouchet, P.; et al. (1987). Infrared photometry of SN 1987A - The first four months. Vol. 177. European Southern Observatory. p. 79. Bibcode:1987ESOC...26...79B.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Roche, P.F.; et al. (1989). "Old cold dust heated by supernova 1987A". Nature. 337: 533. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..533R. doi:10.1038/337533a0.

- ^ Bouchet, P.; Danziger, J.; Lucy, L. (1989). "Supernova 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud". IAU Circular (4933). Bibcode:1989IAUC.4933....1B.

- ^ Danziger, J.; et al. (1989). "Supernova 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud". IAU Circular (4746). Bibcode:1989IAUC.4933....1B.

- ^ Felten, J.E.; Dwek, E. (1989). "Infrared and optical evidence for a dust cloud behind supernova 1987A". Nature. 339: 123. Bibcode:1989Natur.339..123F. doi:10.1038/339123a0.

- ^ Lucy, L.; et al. (1989). "Dust Condensation in the Ejecta of SN 1987 A". Lecture Notes in Physics. 350: 164. Bibcode:1989LNP...350..164L. doi:10.1007/BFb0114861.

- ^

Lucy, L.; et al. (1991). Woosley, S.E. (ed.). Dust Condensation in the Ejecta of Supernova 1987A - Part Two. Springer Verlag New York. p. 82. Bibcode:1991supe.conf...82L. ISBN 0387970711.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Cernuschi, F.; Marsicano, F.; Codina, S. (1967). "Contribution to the theory on the formation of cosmic grains". Annales d'Astrophysique. 30: 1039. Bibcode:1967AnAp...30.1039C.

- ^ Liu, N.; et al. (2018). "Late formation of silicon carbide in type II supernovae". Science Advances. 4 (1): 1054. Bibcode:2018SciA....4O1054L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao1054.

Sources

- Graves, G. J .M.; et al. (2005). "Limits from the Hubble Space Telescope on a point source in SN 1987A". Astrophysical Journal. 629 (2): 944–959. arXiv:astro-ph/0505066. Bibcode:2005ApJ...629..944G. doi:10.1086/431422.

Further reading

- Kirshner, R. P. (1988). "Death of a Star". National Geographic. 173 (5): 619–647.

External links

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Picture of Supernova 1987A (January 24, 1997)

- AAVSO: More information on the discovery of SN 1987A

- Rochester Astronomy discovery timeline

- Light curves and spectra on the Open Supernova Catalog

- Light echoes from Sn1987a, Movie with real images by the group EROS2

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Animation of light echoes from SN1987A (January 25, 2006)

- SN 1987A at ESA/Hubble

- Supernova 1987A, WIKISKY.ORG

- More information at Phil Plait's Bad Astronomy site

- 3D View of Supernova's 'Heart' Sheds New Light on Star Explosions (Images) - Space.com