Ethics in the Bible: Difference between revisions

Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) →Human life and personal relationships: copied material--copied material I wrote for Christianity and civilization and putting it here--will modify later |

Jenhawk777 (talk | contribs) →Human life and personal relationships: material copied from Christianity in civilization that I wrote--will modify and shorten for this application now that it's here |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

This include biblical views of marriage; sexual ethics; and the ethics of speech. |

This include biblical views of marriage; sexual ethics; and the ethics of speech. |

||

W.E.H.Lecky gives the now classical account of the sanctity of human life in his history of European morals saying Christianity "formed a new standard, higher than any which then existed in the world..."<ref name="W. E. H. Lecky">{{cite book| last=Lecky| first=W.E.H.|title=HIstory of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne|volume=2| year=1920| publisher=Longman's, Green, and Co.| location=London, England}}</ref> Christian ethicist [[David P. Gushee]] says "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a committment to life's sanctity..."<ref name="David P. Gushee">{{cite book| last=Gushee| first= David P.| title=In the Fray: Contesting Christian Public Ethics, 1994–2013| year=2014| publisher=Cascade Books| location =Eugene, Oregon,| isbn=978-1-62564-044-4| page=109}}</ref> John Keown, a professor of Christian ethics distinguishes this 'sanctity of life' doctrine from "a quality of life approach, which recognizes only instrumental value in human life, and a vitalistic approach, which regards life as an absolute moral value... [Kewon says it is the] sanctity of life approach ... which embeds a presumption in favor of preserving life, but concedes that there are circumstances in which life should not be preserved at all costs", and it is this which provides the solid foundation for law concerning end of life issues.<ref name="Elizabeth Wicks">{{cite book| last=Wicks| first= Elizabeth| title=The State and the Body: Legal Regulation of Bodily Autonomy| year = 2016| publisher= Hart Publishing Co.| location=Portland, Oregon| isbn=978-1-84946-779-7|page=74,75}}</ref> |

W.E.H.Lecky gives the now classical account of the sanctity of human life in his history of European morals saying Christianity "formed a new standard, higher than any which then existed in the world..."<ref name="W. E. H. Lecky">{{cite book| last=Lecky| first=W.E.H.|title=HIstory of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne|volume=2| year=1920| publisher=Longman's, Green, and Co.| location=London, England}}</ref> Christian ethicist [[David P. Gushee]] says "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a committment to life's sanctity..."<ref name="David P. Gushee">{{cite book| last=Gushee| first= David P.| title=In the Fray: Contesting Christian Public Ethics, 1994–2013| year=2014| publisher=Cascade Books| location =Eugene, Oregon,| isbn=978-1-62564-044-4| page=109}}</ref> John Keown, a professor of Christian ethics distinguishes this 'sanctity of life' doctrine from "a quality of life approach, which recognizes only instrumental value in human life, and a vitalistic approach, which regards life as an absolute moral value... [Kewon says it is the] sanctity of life approach ... which embeds a presumption in favor of preserving life, but concedes that there are circumstances in which life should not be preserved at all costs", and it is this which provides the solid foundation for law concerning end of life issues.<ref name="Elizabeth Wicks">{{cite book| last=Wicks| first= Elizabeth| title=The State and the Body: Legal Regulation of Bodily Autonomy| year = 2016| publisher= Hart Publishing Co.| location=Portland, Oregon| isbn=978-1-84946-779-7|page=74,75}}</ref> |

||

Early Church Fathers advocated against adultery, polygamy, homosexuality, pederasty, bestiality, prostitution, and incest while advocating for the sanctity of the marriage bed.<ref name="witte20">Witte (1997), p. 20.</ref> The central Christian prohibition against such ''porneia'', which is a single name for that array of sexual behaviors, "collided with deeply entrenched patterns of Roman permissiveness where the legitimacy of sexual contact was determined primarily by status. St.Paul, whose views became dominant in early Christianity, made the body into a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine. Same-sex attraction spelled the estrangement of men and women at the very deepest level of their inmost desires. Paul's over-riding sense that gender—rather than status or power or wealth or position—was the prime determinant in the propriety of the sex act was momentous. By boiling the sex act down to the most basic constituents of male and female, Paul was able to describe the sexual culture surrounding him in transformative terms."<ref name="Kyle Harper">{{cite book| last=Harper| first=Kyle| title=From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity| year=2013| publisher=Harvard University Press|location=Cambridge, Massachusettes| isbn=978-0-674-07277-0 |page=4}}</ref>{{rp|12,92}} |

|||

Christian sexual ideology is inextricable from its concept of freewill. "In its original form, Christian freewill was a cosmological claim—an argument about the relationship between God's justice and the individual... as Christianity became intermeshed with society, the discussion shifted in revealing ways to the actual psychology of volition and the material constraints on sexual action... The church's acute concern with volition places Christian philosophy in the liveliest currents of imperial Greco-Roman philosophy [where] orthodox Christians offered a radically distinctive version of it."<ref name="Kyle Harper"/>{{rp|14}} The Greeks and Romans said our deepest moralities depend on our social position which is given to us by fate. Christianity "preached a liberating message of freedom. It was a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being as a sexual being, free, frail and awesomely responsible for one's own self to God alone. It was a revolution in the nature of society's claims on the moral agent... There are risks in over-estimating the change in old patterns Christianity was able to begin bringing about; but there are risks, too, in underestimating Christianization as a watershed."<ref name="Kyle Harper"/>{{rp|14–18}} |

|||

===Economic ethics=== |

===Economic ethics=== |

||

Revision as of 18:20, 9 August 2018

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Ethics in the Bible are the ideas concerning right and wrong actions that exist in scripture in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. Biblical accounts contain numerous prescriptions or laws that people use as guides to action.

Biblical moral themes

Philosopher Alan Mittleman explains biblical ethics is not like most other western ethical theories. It is seldom philosophical in that it presents neither a systematic nor a deductive formal ethical argument. Instead, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character. This moral reasoning is part of a broad normative covenantal tradition where duty and virtue are inextricably tied together in a mutually reinforcing manner. It uses legal texts, wise sayings, commentaries, and narratives of ordinary people with specific issues, to offer, rather than argue, a moral vision that is suggestive and case-based. Mittleman explains this leaves the reader to engage intellectually with moral reasoning of their own.[1]: 1, 2

Political ethics

Political theorist Michael Walzer says "the Bible is, above all, a religious book, but it is also a political book."[2] There is no political theory, as such, in the Bible, however, the Bible does contain legal codes, rules for war and peace, "ideas about justice and obligation, social criticism, visions of the good society, and accounts of exile and dispossession." Therefore, Walzer says, it is possible to work out a comparative politics.[2]: xii Walzer says politics in the Bible is similar to modern "consent theory" which requires agreement between the governed and the authority based on full knowledge and the possibility of refusal.[2]: 5–6 He goes on to say politics in the Bible also models "social contract theory" which says a person's moral obligations to form the society in which they live are dependent on that agreement.[2]: 7 This implies respect for the authority: an admiration on the part of the Israelites for this particular God and his laws which is not a result of law, but pre-exists law, making it possible for them to recognize the righteousness of the law as it was received.[3]. This is what makes it possible for someone like Amos, "an herdsman and gatherer of sycamore fruit," to confront Priests and Kings and remind them of their obligations. Moral law is, therefore, politically democratized in the Bible.[2]: 7–15

War and peace

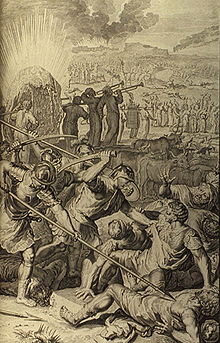

Warfare is a topic the Bible addresses ethically, directly and indirectly, in four ways: there are verses that support pacifism, and verses that support non-resistance; 4th century theologian Augustine found the basis of just war in the Bible, and preventive war which is sometimes called crusade has also been supported using Bible texts.[4]: 13–37 Susan Niditch explores the range of war ideologies in ancient Near Eastern culture saying, "...To understand attitudes toward war in the Bible is thus to gain a handle on war in general..."[5]

In the Hebrew Bible warfare includes the Amalekites, Canaanites, Moabites, and the record in Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and both books of Kings.[6][7][8][9] For the modern reader, the ethics of conquest is problematic. Yet Walzberg says there is no reason to assume it was so for the biblical writers. God commands the Israelites to conquer the Promised Land, placing city after city "under the ban," the herem of total war,[10] which meant every man, woman and child was supposed to be killed[11]: 319–320 [12] thus leading many scholars to characterize these as commands to commit genocide.[13][14][15]: 17–30 [16]: 9 [17]: 83 Starting in Joshua 9, after the conquest of Ai, the battles are described as self-defense, and the priestly authors of Leviticus, and the Deuteronomists, are careful to give God moral reasons for his commandment[18][2]: 7 [16]: 34

The biblical texts also include rules for limited war, which from Deuteronomy 20 on, are joined with the herem total war doctrines without one superseding the other. The rules of military engagement begin at Deuteronomy 20:10-14 [19] which follows a list of those exempt from battle. It is a limited war doctrine consistent with Amos and First and Second Kings.[2]: 42 It also outlines the proper treatment of female captives: marry them or set them free--whereas herem requires them to be killed.[2]: 43 Verses 15 to 18 are very old, suggesting "the addition of herem to an older siege law." Walzer explains there are two stories of conquest in the Bible and two sets of laws supporting each.[2]: 36–43

Criminal justice

Human life and personal relationships

Prescriptive utterances (commandments) are found throughout the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament, some related to inter-human relationships (the prohibition against murder) while others focus on issues of worship and ritual (e.g. the Day of Atonement festival). Rabbinic tradition classically schematizes these prescriptions into 613 mitzvot, beginning with "Be fruitful and multiply" (God's command to all life) and continuing on to the seven laws of Noah (addressed to all humanity) and the several hundred laws which apply specifically to the Israelites (such as the kashrut dietary laws). Rabbinic tradition also records the aforementioned distinction between commandments that relate to man's interaction with fellow man (בין אדם לחבירו) and those that affect his relationship with God (בין אדם למקום).[citation needed] Many commandments are remarkable in their blending of the two roles. For example, observance of Shabbat is couched in terms of recognizing God's sovereignty and creation of the world, while also being presented as a social-justice measure to prevent overworking one's employees, slaves, and animals. As a result, the Bible consistently binds worship of the Divine to ethical actions and ethical actions with worship of the Divine.[1]: 1–14

This include biblical views of marriage; sexual ethics; and the ethics of speech. W.E.H.Lecky gives the now classical account of the sanctity of human life in his history of European morals saying Christianity "formed a new standard, higher than any which then existed in the world..."[20] Christian ethicist David P. Gushee says "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a committment to life's sanctity..."[21] John Keown, a professor of Christian ethics distinguishes this 'sanctity of life' doctrine from "a quality of life approach, which recognizes only instrumental value in human life, and a vitalistic approach, which regards life as an absolute moral value... [Kewon says it is the] sanctity of life approach ... which embeds a presumption in favor of preserving life, but concedes that there are circumstances in which life should not be preserved at all costs", and it is this which provides the solid foundation for law concerning end of life issues.[22]

Early Church Fathers advocated against adultery, polygamy, homosexuality, pederasty, bestiality, prostitution, and incest while advocating for the sanctity of the marriage bed.[23] The central Christian prohibition against such porneia, which is a single name for that array of sexual behaviors, "collided with deeply entrenched patterns of Roman permissiveness where the legitimacy of sexual contact was determined primarily by status. St.Paul, whose views became dominant in early Christianity, made the body into a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine. Same-sex attraction spelled the estrangement of men and women at the very deepest level of their inmost desires. Paul's over-riding sense that gender—rather than status or power or wealth or position—was the prime determinant in the propriety of the sex act was momentous. By boiling the sex act down to the most basic constituents of male and female, Paul was able to describe the sexual culture surrounding him in transformative terms."[24]: 12, 92

Christian sexual ideology is inextricable from its concept of freewill. "In its original form, Christian freewill was a cosmological claim—an argument about the relationship between God's justice and the individual... as Christianity became intermeshed with society, the discussion shifted in revealing ways to the actual psychology of volition and the material constraints on sexual action... The church's acute concern with volition places Christian philosophy in the liveliest currents of imperial Greco-Roman philosophy [where] orthodox Christians offered a radically distinctive version of it."[24]: 14 The Greeks and Romans said our deepest moralities depend on our social position which is given to us by fate. Christianity "preached a liberating message of freedom. It was a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being as a sexual being, free, frail and awesomely responsible for one's own self to God alone. It was a revolution in the nature of society's claims on the moral agent... There are risks in over-estimating the change in old patterns Christianity was able to begin bringing about; but there are risks, too, in underestimating Christianization as a watershed."[24]: 14–18

Economic ethics

The Bible gives images of social justice, economics and labor, and business ethics.

Environmental ethics

The Bible has a great deal to say on bio-ethics and animals.

History

Axial age (8th to the 3rd century BCE.)

Pre-modern era (before 1600)

Modern Era (1600-1950)

Post-modern Era (1950-Present)

Theological foundations of ethics in the Bible

Doctrine of God

The Bible assumes the existence of God.

Creation and its implications

In 1895 Hermann Gunkel observed that most Ancient Near Eastern creation stories contain a theogony depicting a god doing combat with other gods thus including violence as normative in the founding of their cultures.[25] For example, in the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish, the first step of creation has Marduk fighting and killing Tiamat, a chaos monster, to establish order.[26] Theologian Christopher Hays says Hebrew stories use a term for dividing (bâdal; separate, make distinct) that is an abstract concept more reminiscent of a Mesopotamian tradition using non-violence at creation. Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann says "God's characteristic action is to "speak"... God "calls the world into being... The way of God with his world is the way of language."[27] Old Testament scholar Jerome Creach says Gen. 1:1–2:4a was normative for those who gave the Old Testament canon its present shape.[28]: 4–5, 16, 18

The world's first civilizations were Mesopotamian sacred states ruled in the name of a divinity or by rulers who were themselves seen as divine. Rulers, and the priests, soldiers and bureaucrats who carried out their will, were a small minority who kept power by exploiting the many.[29]

Conscience

Covenant and tradition

Salvation and the Holy Spirit

The main dispute of the Council of Jerusalem, whether non-Jewish converts to Christianity should be considered bound to the Old Testament laws, is addressed elsewhere in the New Testament, e.g. regarding dietary laws:

"Don't you perceive that whatever goes into the man from outside can't defile him, because it doesn't go into his heart, but into his stomach, then into the latrine, thus making all foods clean?"-Mark 7:18. (See also Mark 7)

or regarding divorce:

"I tell you that whoever puts away his wife, except for the cause of sexual immorality, makes her an adulteress; and whoever marries her when she is put away commits adultery."-Matthew 5:31. (See also Mark 5)

The central teachings of Jesus are presented in the Sermon on the Mount,[30] notably the "golden rule" and the prescription to "love your enemies" and "turn the other cheek".

"You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.' But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you."-Matthew 5:43–44

Elsewhere in the New Testament (for example, the "Farewell Discourses" of John 14 through 16) Jesus elaborates on what has become known the commandment of love[according to whom?], repeated and elaborated upon in the epistles of Paul (1 Corinthians 13 etc.), see also The Law of Christ and The New Commandment.

War

Hans Van Wees says the conquest campaigns are largely fictional.[10][31] In the archaeological community, the Battle of Jericho has been thoroughly studied, and the consensus of modern scholars is the battles described in the Book of Joshua are not realistic, are not supported by the archeological record, and are not consistent with other texts in the Bible; for example, the Book of Joshua describes the extermination of the Canaanite tribes, yet at a later time Judges 1:1-2:5 suggests that the extermination was not complete.[32][33]

Historian Paul Copan and philosopher Matthew Flannagan say the violent texts of ḥerem warfare are "hagiographic hyperbole", a kind of historical writing found in the Book of Joshua and other Near Eastern works of the same era, are not intended to be literal, contain hyperbole, formulaic language, and literary expressions for rhetorical effect—like when sports teams use the language of “totally slaughtering” their opponents.[34] John Gammie concurs, saying the Bible verses about "utterly destroying" the enemy are more about pure religious devotion than an actual record of killing people.[35] Gammie references Deuteronomy 7:2-5 in which Moses presents ḥerem as a precondition for Israel to occupy the land with two stipulations: one is a statement against intermarriage (vv. 3–4), and the other concerns the destruction of the sacred objects of the residents of Canaan (v. 5) but neither involves killing.[36]

C. L. Crouch compares the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah to Assyria, saying their similarities in cosmology and ideology gave them similar ethical outlooks on war.[37] Both Crouch and Lauren Monroe, professor of Near Eastern studies at Cornell, agree this means the ḥerem type of total war was not strictly an Israelite practice but was a common approach to war for many Near Eastern people of the Bronze and Iron Ages.[38]: 335 For example, the Mesha Stele says that King Mesha of Moab fought in the name of his god Chemosh and that he subjected his enemies to ḥerem.[37]: intro, 182, 248 [16]: 10, 19

Comparisons with other ethical systems

Criticism

Several Biblical prescriptions may not correspond to modern notions of justice in relation to concepts such as slavery (Lev. 25:44-46), intolerance of religious pluralism (Deut. 5:7, Deut. 7:2-5) or of freedom of religion (Deut. 13:6-12), discrimination and racism (Lev. 21:17-23, Deut. 23:1-3), treatment of women, honor killing (Ex. 21:17, Leviticus 20:9, Ex. 32:27-29), genocide (Num. 31:15-18, 1 Sam. 15:3), religious wars, and capital punishment for sexual behavior like adultery and sodomy and for Sabbath breaking (Num. 15:32-36).

The Book of Proverbs recommends disciplining a child:

Foolishness is bound in the heart of a child; but the rod of correction shall drive it far from him.

— Proverbs 22:15

Simon Blackburn states that the "Bible can be read as giving us a carte blanche for harsh attitudes to children, the mentally handicapped, animals, the environment, the divorced, unbelievers, people with various sexual habits, and elderly women".[39]

Elizabeth Anderson, a Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, states that "the Bible contains both good and evil teachings", and it is "morally inconsistent".[40] Bertrand Russell stated that, "It seems to me that the people who have held to it [the Christian religion] have been for the most part extremely wicked....I say quite deliberately that the Christian religion, as organized in its churches, has been and still is the principal enemy of moral progress in the world."[41]

Euthyphro Dilemma

A central problem in religiously motivated ethics is the apparent tautology inherent in the concept that what is commanded by God is morally right. This line of reasoning is introduced most famously in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, which asks whether something is right because the gods love it, or whether the gods love it because it is right.

Moral relativism

The predominant Christian view[citation needed] is that Jesus mediates a New Covenant relationship between God and his followers and abolished some Mosaic Laws, according to the New Testament (Hebrews 10:15–18; Gal 3:23–25; 2 Cor 3:7–17; Eph 2:15; Heb 8:13, Rom 7:6 etc.). From a Jewish perspective however, the Torah was given to the Jewish people as an eternal covenant (Exod 31:16–17, Exod 12:14–17, Mal 3:6–7) and will never be replaced or added to (Deut 4:2, 13:1). There are differences of opinion as to how the new covenant affects the validity of biblical law. The differences are mainly as a result of attempts to harmonize biblical statements to the effect that the biblical law is eternal (Exodus 31:16–17, 12:14–17) with New Testament statements that suggest that it does not now apply at all, or at least does not fully apply. Most biblical scholars admit the issue of the Law can be confusing and the topic of Paul and the Law is still frequently debated among New Testament scholars[42] (for example, see New Perspective on Paul, Pauline Christianity); hence the various views.

God's benevolence

A central issue in monotheist ethics is the problem of evil, the apparent contradiction between a benevolent, all-powerful God and the existence of evil and hell (see Problem of Hell). Theodicy seeks to explain why one may simultaneously affirm God's goodness, and the presence of evil in the world. Descartes in his Meditations considers, but rejects, the possibility that God is an evil demon ("dystheism").

The Bible contains numerous examples seemingly unethical acts of God.

- In the Book of Exodus, God deliberately "hardened Pharaoh's heart", making him even more unwilling to free the Hebrew slaves (Exod 4:21, Rom 9:17–21).

- Genocidal commands of God in Deuteronomy, such as the call to eradicate all the Canaanite tribes including children and infants (Deut 20:16–17). According to the Bible, this was to fulfill God's covenant to Israel, the "promised land" to his chosen people.(Deuteronomy 7:1–25)

- God ordering the Israelites to undertake punitive military raids against other tribes. This happened, for instance, to the Midianites of Moab, who had enticed some Israelites into worshipping local gods (Numbers 25:1–18). The entire tribe was exterminated, except for the young virgin girls, who were kept by the Israelites as slaves (Numbers 31:1–54). In 1 Samuel 15:3, God orders the Israelites to "attack the Amalekites and totally destroy everything that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys." [43]

- In the Book of Job, God allows Satan to plague His loyal servant Job with devastating tragedies leaving all his children dead and himself poor. The nature of Divine justice becomes the theme of the entire book. However, after he got through his troubles his health was restored and all he had was doubled.

- Sending evil spirits to people (1 Samuel 18:10, Judges 9:23).

- Punishing the innocent for the sins of other people (Isa 14:21, Deut 23:2, Hosea 13:16).

- In the Book of Isaiah, God created all natural disasters/the evil in the world. (Isaiah 45–7)

The Old Testament

Elizabeth Anderson criticizes commands God gave to men in the Old Testament, such as: kill adulterers, homosexuals, and "people who work on the Sabbath" (Leviticus 20:10; Leviticus 20:13; Exodus 35:2, respectively); to commit ethnic cleansing (Exodus 34:11-14, Leviticus 26:7-9); commit genocide (Numbers 21: 2-3, Numbers 21:33–35, Deuteronomy 2:26–35, and Joshua 1–12); and other mass killings.[44] Anderson considers the Bible to permit slavery, the beating of slaves, the rape of female captives in wartime, polygamy (for men), the killing of prisoners, and child sacrifice.[44] She also provides a number of examples to illustrate what she considers "God's moral character": "Routinely punishes people for the sins of others ... punishes all mothers by condemning them to painful childbirth", punishes four generations of descendants of those who worship other Gods, kills 24,000 Israelites because some of them sinned (Numbers 25:1–9), kills 70,000 Israelites for the sin of David in 2 Samuel 24:10–15, and "sends two bears out of the woods to tear forty-two children to pieces" because they called someone names in 2 Kings 2:23–24.[45]

Blackburn provides examples of Old Testament moral criticisms such as the phrase in Exodus 22:18 that has "helped to burn alive tens or hundreds of thousands of women in Europe and America": "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live," and notes that the Old Testament God apparently has "no problems with a slave-owning society", considers birth control a crime punishable by death, and "is keen on child abuse".[46] Additional examples that are questioned today are: the prohibition on touching women during their "period of menstrual uncleanliness (Lev. 15:19–24)", the apparent approval of selling daughters into slavery (Exodus 21:7), and the obligation to put to death someone working on the Sabbath (Exodus 35:2).[47]

The New Testament

Anderson criticizes what she terms morally repugnant lessons of the New Testament. She claims that "Jesus tells us his mission is to make family members hate one another, so that they shall love him more than their kin (Matt 10:35-37)", that "Disciples must hate their parents, siblings, wives, and children (Luke 14:26)", and that Peter and Paul elevate men over their wives "who must obey their husbands as gods" (1 Corinthians 11:3, 14:34-5, Eph. 5:22-24, Col. 3:18, 1 Tim. 2: 11-2, 1 Pet. 3:1).[48] Anderson states that the Gospel of John implies that "infants and anyone who never had the opportunity to hear about Christ are damned [to hell], through no fault of their own".[49]

Blackburn criticizes what he terms morally suspect themes[need quotation to verify] of the New Testament.[50] He notes some "moral quirks" of Jesus: that he could be "sectarian" (Matt 10:5–6),[51] racist (Matt 15:26 and Mark 7:27), and placed no value on animal life (Luke 8: 27–33).

See also

- Antinomianism#Biblical law in Christianity

- Antisemitism and the New Testament

- Brotherly love (philosophy)

- But to bring a sword

- The Bible and slavery

- Criticism of the Bible

- Christianity and homosexuality

- Women in the Bible

- The Bible and death penalty

References

- ^ a b Mittleman, Alan L. (2012). A Short History of Jewish Ethics: Conduct and Character in the Context of Covenant. Chichester, West Suffix: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8942-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Walzer, Michael (2012). In God's Shadow: Politics in the Hebrew Bible. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18044-2.

- ^ Deut 4:6–8

- ^ Clouse, Robert G. (1986). War: Four Christian Views. Winona Lake, Indiana: BMH Books.

- ^ Niditch, Susan (1993). War in the Hebrew Bible: A study in the Ethics of Violence. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-507638-9.

- ^ Hunter, A. G. (2003). Bekkencamp, Jonneke; Sherwood, Yvonne (eds.). Denominating Amalek: Racist stereotyping in the Bible and the Justification of Discrimination", in Sanctified aggression: legacies of biblical and post biblical vocabularies of violence. Continuum Internatio Publishing Group. pp. 92–108.

- ^ Ruttenberg, Danya (Feb 1987). Jewish Choices, Jewish Voices: War and National Security. p. 54.

- ^ Fretheim, Terence (2004). "'I was only a little angry': Divine Violence in the Prophets". Interpretation. 58.4: 365–375.

- ^ Stone, Lawson (1991). "Ethical and Apologetic Tendencies in the Redaction of the Book of Joshua". Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 53.1: 33.

- ^ a b Deut 20:16–18

- ^ Ian Guthridge (1999). The Rise and Decline of the Christian Empire. Medici School Publications, Australia. ISBN 978-0-9588645-4-1.

the Bible also contains the horrific account of what can only be described as a "biblical holocaust"

. - ^ Ruttenberg, Danya, Jewish Choices, Jewish Voices: War and National Security Danya Ruttenberg (Ed.) page 54 (citing Reuven Kimelman, "The Ethics of National Power: Government and War from the Sources of Judaism", in Perspectives, Feb 1987, pp 10-11)

- ^ Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A.Dirk, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ A. G. Hunter "Denominating Amalek: Racist stereotyping in the Bible and the Justification of Discrimination", in Sanctified aggression: legacies of biblical and post biblical vocabularies of violence, Jonneke Bekkenkamp, Yvonne Sherwood (Eds.). 2003, Continuum Internatio Publishing Group, pp 92-108

- ^ Grenke, Arthur (2005). God, greed, and genocide: the Holocaust through the centuries. New Academia Publishing.

- ^ a b c Creach, Jerome (Jul 2016). "Violence in the Old Testament". The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-154 (inactive 2018-04-11). Retrieved 23 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2018 (link) - ^ Siebert, Eric (2012). The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament's Troubling Legacy. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-2432-4.

- ^ Deut 9:5

- ^ Deut 20:10–14

- ^ Lecky, W.E.H. (1920). HIstory of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne. Vol. 2. London, England: Longman's, Green, and Co.

- ^ Gushee, David P. (2014). In the Fray: Contesting Christian Public Ethics, 1994–2013. Eugene, Oregon,: Cascade Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-62564-044-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Wicks, Elizabeth (2016). The State and the Body: Legal Regulation of Bodily Autonomy. Portland, Oregon: Hart Publishing Co. p. 74,75. ISBN 978-1-84946-779-7.

- ^ Witte (1997), p. 20.

- ^ a b c Harper, Kyle (2013). From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-674-07277-0.

- ^ Gunkel, Hermann; Zimmern, Heinrich (2006). Creation And Chaos in the Primeval Era And the Eschaton: A Religio-historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. Translated by Whitney Jr., K. William. Grand Rapids: Eerdman's.

- ^ Mathews, "Kenneth A." (1996). The New American Commentary: Genesis 1-11:26. Vol. 1A. Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman and Holman Publishers. pp. 92–95. ISBN 978-0-8054-0101-1.

- ^ Brueggemann, Walter (2010). Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster Jon Know Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-664-23437-9.

- ^ Creach, Jerome F.D. (2013). Violence in Scripture: Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23978-7.

- ^ Andrea, Alfred J.; Overfield, James H. (2016). The Human Record: To 1500 Sources of Global History. Vol. 1 (eighth ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. pp. 6–17. ISBN 978-1-285-87023-6.

- ^ The Sermon on the mount: a theological investigation by Carl G. Vaught 2001 ISBN 978-0-918954-76-3 pages xi–xiv

- ^ Van Wees, Hans (April 15, 2010). "12, Genocide in the Ancient World". In Bloxham, Donald; Dirk Moses, A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191613616.

- ^ Ehrlich, pp 117-119

- ^ Judges 1:1–2:5

- ^ Copan, Paul; Flannagan, Matthew (2014). Did God Really Command Genocide? Coming to Terms With the Justice of God. Baker Books. pp. 84–109.

- ^ Gammie, John G. (1970). "The Theology of Retribution in the Book of Deuteronomy". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 32.1. Catholic Biblical Association: 1–12. JSTOR 43712745.

- ^ Seibert, Eric A. (2009). Disturbing divine behavior: troubling Old Testament images of God. Fortress Press.

- ^ a b "C.L. Crouch", C. L. (2009). War and Ethics in the Ancient Near East: Military Violence in Light of Cosmology and History. Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 194.

- ^ Monroe, Lauren A. S. (2007). "Israelite, Moabite and Sabaean War- Ḥērem Traditions and the Forging of National Identity: Reconsidering the Sabaean Text RES 3945 in Light of Biblical and Moabite Evidence". Vetus Testamentum. 57.3.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1957). Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. New York: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-671-20323-8.

- ^ Gundry, ed., Five Views on Law and Gospel. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993).

- ^ The Dominion of Love: Animal Rights According to the Bible, Norm Phelps, p. 14

- ^ a b Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 10, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Elizabeth Anderson, "If God is Dead, Is Everything Permitted?" In Hitchens, Christopher (2007). The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (2001). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-19-280442-6.

- ^

Blackburn, Simon (2003). Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. OUP. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780191577925. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

Then the persona of Jesus in the Gospels has his fair share of moral quirks. He can be sectarian: 'Go not into the way of the Gentiles, and into any city of the Samaritans enter ye not. But go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel' (Matt. 10:5-6).