Hawaiian Kingdom

Kingdom of Hawaiʻi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1795–1894 | |||||||||

Coat of Arms

| |||||||||

| Motto: Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono | |||||||||

| Anthem: Hawaiʻi Ponoʻi | |||||||||

Kingdom of Hawaii | |||||||||

| Capital | Lahaina (1820-1845) Honolulu | ||||||||

| Common languages | Hawaiian & English | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Unification of Islands | 1795 - 1810 1795 | ||||||||

| January 17, 1893 | |||||||||

• Declaration of the Republic of Hawaii | July 4, 1894 1894 | ||||||||

| Currency | U.S. dollar, Hawaiian dollar (1879) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

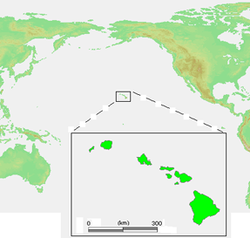

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established during 1795 - 1810 with the subjugation of the smaller independent chiefdoms of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi and Kauaʻi by the chiefdom of Hawaiʻi (or the "Big Island") into one unified government.

Formation

Through swift and bloody battles, led by a warrior chief later immortalized as Kamehameha the Great, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established with the help of such British sailors as John Young and Alexander Adams and western weapons. Although successful in attacking both Oʻahu and Maui, he failed to secure a victory in Kauaʻi, his effort hampered by a storm. Eventually, Kauaʻi's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha's rule. The unification ended the feudal society of the Hawaiian islands transforming it into a "modern", independent constitutional monarchy crafted in the tradition of European empires.

Government

Government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was transformed in phases, each phase created by the promulgation of the constitutions of 1840, 1852, 1864 and 1887. Each successive constitution can be seen as a decline in the power of the monarch in favor of popularly elected representative government. The head of state and head of government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was the monarch. He or she oversaw the Privy Council which was charged with administration. A royal cabinet, the Privy Council consisted of ministers in charge of departments much like that of the American system. These ministers also acted as the monarch's primary advisors.

The 1840 Constitution created a bicameral parliament in charge of legislation. The two houses of the legislature were the House of Representatives (directly elected by popular vote) and the House of Nobles (appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet). The same constitution created a judiciary, charged with overseeing the courts and interpretation of laws. The Supreme Court was led by the Chief Justice, appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet.

The islands of Hawaiʻi were divided into smaller administrative divisions: Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi. Kauaʻi region included Niʻihau, while Maui region included Kahoʻolawe, Lānaʻi and Molokaʻi. Each administrative region was governed by a governor appointed by the monarch.

Kamehameha Dynasty

From 1810 to 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was ruled by two major dynastic families: the Kamehameha Dynasty and the Kalākaua Dynasty. Five members of the Kamehameha family would lead the government as its king. Two of them, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great himself. For a period between Liholiho and Kauikeaouli's reigns, the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Kaʻahumanu, ruled as Queen Regent and Kuhina Nui, or Prime Minister.

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family tragically ended in 1872 with the death of Lot (Kamehameha V). Upon his deathbed, he summoned Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. She was the last direct Kamehameha family member surviving. She refused the crown and throne in favor of a private life with her husband, Charles Reed Bishop. Lot died before naming an alternative heir.

- Kamehameha I, (1795-1819)

- Kamehameha II, Liholiho, (1819-1824)

- Kamehameha III, Kauikeaouli, (1825-1854)

- Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho, (1854-1863)

- Kamehameha V, Lot Kapuāiwa, (1863-1872)

The Paulet Affair (1843)

On 13 February 1843, Lord George Paulet, of HMS Carysfort, attempted to annex the islands for alleged insults and malpractices against British subjects.[1] Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing:

- Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?'

- Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified.

- Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843.

- Kamehameha III.

- Kekauluohi.[2]

Dr. Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the Minister of Finance for the Kingdom of Hawaii, secretly arranged for General J.F.B. Marshall to be the King's envoy to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions.[3] Marshall was able to secretly convey the Kingdom's complaint to the Vice Consul of Britain in Tepec, posing as a commercial agent of Ladd & Co., a company with friendly relations with the Kingdom.

Marshall's complaint was forwarded to Rear Admiral Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, who arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on H.B.M.S. Dublin from Valparaiso, Chile. Admiral Thomas apologized to Kamehameha III for Paulet's actions, and restored Hawaiian sovereignty on the 31st of July, 1843.

On the 28th of November, 1843, a joint declaration by the governments of France and England declared they would "consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, neither directly nor under the title of protectorate, nor under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed." [4] The United States notably declined to join with France and England in this statement.

Elected monarchy

The refusal of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to take the crown and throne as Queen of Hawaiʻi forced the legislature of the Kingdom to declare an election to fill the royal vacancy. From 1872 to 1873, several distant relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In a ceremonial popular vote, and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo (1873-1874) became Hawaiʻi's first of two elected monarchs.

Kalākaua Dynasty

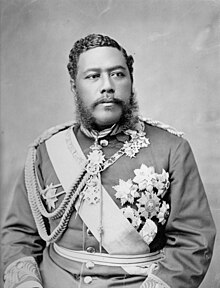

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. He died unexpectedly after less than a year as King of Hawaiʻi. Once again, the legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was forced to declare an election to fill the royal vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kalākaua. The 1874 election was opined to be one of the nastiest political campaign seasons in Hawaiʻi history. Both candidates resorted to mudslinging and rumors. David Kalākaua was elected the second elected King of Hawaiʻi, but without the same ceremonial popular vote Lunalilo had. The choice of the legislature was so controversial following his ascension to the throne that U.S. troops were called upon to suppress rioting that had broken out in protest of his win over Emma.

Hoping to avoid uncertainty in the monarchy's future, Kalākaua proclaimed several heirs to the throne and defined a royal line of succession. His sister Liliʻuokalani would succeed the throne upon Kalākaua's death. It was indicated that Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani would follow. If she could not produce an heir by birth, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole would rule after her.

- David Kalākaua, (1874-1891)

- Liliʻuokalani, (1891-1893)

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy

Queen Liliʻuokalani was selected as the successor to King Kalākaua by Kalākaua upon his election in 1874. During her brother's reign the monarchy was left impotent by the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. In response to numerous royal corruption scandals, David Kalākaua was ordered under threat of force to sign the constitution stripping the monarchy of much of its power in favor of an administration controlled by the Legislature. Some claim this constitution was the opening salvo to the end of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians (primarily of American and European ancestry, including native-born Hawaiian subjects of foreign descent) organized in response to an attempt by Liliʻuokalani to abrogate the 1887 constitution, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. American troops aboard the USS Boston were landed in Honolulu to protect American lives and property, while a Committee of Safety, a 13 member council, organized the Honolulu Rifles to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the subsequent annexation of Hawaiʻi has recently been cited as the first major instance of American imperialism.[6]

Later, after a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds after an attempted rebellion in 1895, Queen Liliʻuokalani was placed under arrest, tried by a military tribunal of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, convicted of misprision of treason and then imprisoned in her own home.

Sanford B. Dole and his committee declared itself the Provisional Government of the Kingdom of Hawaii on July 17, 1893, removing only the Queen, her cabinet, and her marshal from office. On July 4, 1894 the Republic of Hawaiʻi was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. As a republic, it was the intention of the government to campaign for annexation with the United States of America. The rationale behind annextion included a strong economic component - Hawaiian goods and services exported to the mainland would not be subject to American tariffs, and would benefit from domestic bounties, if Hawaii was part of the United States. This was especially important to the Hawaiian economy after the McKinley Act reduced the effectiveness of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1874 by lowering tariffs on all foreign sugar, and eliminating Hawaii's previous advantage.

The Republic of Hawaii succeeded in its goal when in 1898, Congress approved a joint resolution of annexation creating the U.S. Territory of Hawaiʻi. This followed the precedent of Texas which was also annexed by a joint resolution of Congress. Dole was appointed to be the first governor of the Territory of Hawaii.

Royal estates

Early in its history, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was governed from several locations including coastal towns on the islands of Hawaiʻi and Maui (Lāhainā). It wasn't until the reign of Kamehameha III that a capital was established in Honolulu on the Island of Oʻahu.

By the time Kamehameha V was king, he saw the need to build a royal palace fitting of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi's new found prosperity and standing with the royals of other nations. He commissioned the building of the palace at Aliʻiōlani Hale. He died before it was completed. Today, the palace houses the Supreme Court of the State of Hawaiʻi.

David Kalākaua shared the dream of Kamehameha V to build a palace, and eagerly desired the trappings of European royalty. He commissioned the construction of ʻIolani Palace from which he and his successor would govern. In later years, the palace would become his sister's makeshift prison under guard by the U.S. Armed Forces, the site of the official raising of the U.S. flag during annexation, and then the site of the territorial governor's and legislature's offices.

Palaces

- ʻĀinahau, Home of Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani

- Aliʻiōlani Hale, Originally designed as a Palace for Kamehameha V, although Kamehameha V later decided to convert the building into a government building during construction

- Hanaiakamalama, Summer Palace of Queen Emma

- Huliheʻe Palace, Palace of Princess Ruth

- Keōua Hale, Palace of Princess Ruth

- ʻIolani Palace, Palace of the Kalākaua Dynasty

Royal grounds

Other notable Hawaiian royals

Kamehameha Dynasty

- Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Kaʻahumanu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Victoria Kamamalu, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Ruth Keʻelikōlani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Keopuolani, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Kinaʻu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Emma Rooke, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Albert Kamehameha, Crown Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Elizabeth Kekaaniau, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Theresa Owana Kaohelelani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

Kalākaua Dynasty

- Victoria Kaʻiulani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaʻole, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Julia Kapiʻolani, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Abigail Campbell Kawananakoa, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- David Kawananakoa, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- William Pitt Leleiohoku, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Miriam K. Likelike, Princess of Hawaiʻi

Other notable royal subjects

Authors and artists

- Henri Berger, composer

- Robert Louis Stevenson, author

Civil leaders

- John Adams Kuakini, governor

- Charles Reed Bishop, businessman and philanthropist

- James Campbell, businessman and philanthropist

- Archibald Cleghorn, businessman and royal consort

- Sanford B. Dole, chief justice

- John Owen Dominis, governor and royal consort

- Gerrit P. Judd, royal advisor

- Kuini Liliha, governor

- Lorrin A. Thurston, lawyer and publisher

- Robert William Wilcox, soldier

- John Young, royal advisor

- Benjamin Dillingham, businessman and industrialist

Religious leaders

- Father Damien, Catholic missionary

- Louis Maigret, Catholic bishop

- Thomas Nettleship Staley, Anglican bishop

References

- ^ http://www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/pearl/hawaii.htm

- ^ The Morgan Report, p500-503

- ^ http://www.alohaquest.com/arbitration/news_polynesian_0011b.htm

- ^ The Morgan Report, p503-517

- ^ U.S. Navy History site

- ^ Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq by Stephen Kinzer, 2006

- Andrade Jr., Ernest (1996). Unconquerable Rebel: Robert W. Wilcox and Hawaiian Politics, 1880-1903. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0870814176.

- Lydia Liliʻuokalani Dominis (1994). Hawaiʻi's Story by Hawaiʻi's Queen Liliʻuokalani. Mutual Publishing Co. ISBN 0-935180-85-0.

- Michael Dougherty (1994). To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History. Hawaiian Style Press. ISBN 0-9633484-0-X.

- Gerard Manley Hopkins (2003). Hawaiʻi: The Past, Present, and Future of Its Island Kingdom: An Historic Account of the Sandwich Islands of Polynesia. Kegan Paul International Ltd. ISBN 0-7103-0781-0.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (2003). Hawaiʻi: A History, from Polynesian Kingdom to American State. Textbook Publishers. ISBN 0-7581-6072-0.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1995). Hawaiian Kingdom: Foundation and Transformation, 1778-1854, Vol. 1. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1995). Hawaiian Kingdom: Twenty Critical Years, 1854-1874, Vol. 2. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-87022-432-8.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1995). Hawaiian Kingdon Volume 3: 1874-1893, the Kalākaua Dynasty. University of Hawaiʻi Press. EAN 9780870224331.

- Aldyth Morris (1995). Liliʻuokalani. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-8248-1543-2.

- Juri Mykkanen (2003). Inventing Politics: A New Political Anthropology of the Hawaiian Kingdom. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-8248-1486-X.

- Niklaus R. Schweizer (1994). His Hawaiian Excellency: The Overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Annexation of Hawaiʻi. Lang, Peter Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-8204-2587-7.

- Thurston Twigg-Smith Hawaiian Sovereignty: Do the Facts Matter?

- Senate Report 227 of the 53rd Congress (The Morgan Report), February 26, 1894

External links

- Overthrow of the Monarchy, Article by Pat Pitzer, Spirit of Aloha, May 1994

- hawaiiankingdom.org, Organization claiming to represent a reinstated Hawaiian Kingdom government

- kenconklin.org Website with articles critical of the claims of sovereignty activists

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |