Capture of Sedalia

| Capture of Sedalia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| M. Jeff Thompson[a] | John D. Crawford | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Shelby's Brigade |

Home guards and Enrolled Missouri Militia 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 1,200 men | c. 830 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

1 dead and 23 wounded Several hundred captured and released or paroled | ||||||

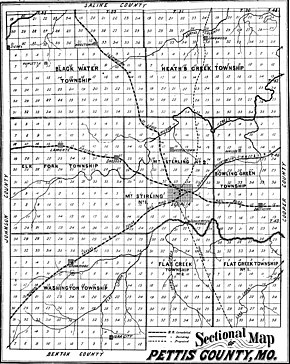

Location within Missouri | |||||||

The capture of Sedalia occurred during the American Civil War when a Confederate force captured the Union garrison of Sedalia, Missouri, on October 15, 1864. Confederate Major General Sterling Price, who was a former Governor of Missouri and had commanded the Missouri State Guard in the early days of the war, had launched an invasion into the state of Missouri on August 29. He hoped to distract the Union from more important areas and cause a popular uprising against Union control of the state. Price had to abandon his goal of capturing St. Louis after a bloody repulse at the Battle of Fort Davidson and moved into the pro-Confederate region of Little Dixie in central Missouri.

Many recruits in the region joined the Confederates in the region, and Price soon needed supplies and weapons for these men. He sent side raids to Glasgow and Sedalia. One of these involved sending a 1,200-man brigade led by Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State Guard towards Sedalia. Despite learning of Union movements in the area, Thompson attacked the town, which was primarily defended by militia. The initial Confederate attack quickly dispersed most of the defenders, although some held out until Thompson brought up the rest of his force. Many of the militiamen were captured. After paroling or releasing their prisoners and plundering the town, the Confederates left to rejoin Price's main force. On October 23, Price was defeated at the Battle of Westport near Kansas City. The Confederates then retreated, suffering defeats at the battles of Mine Creek and Second Newtonia later in October, before eventually entering Texas.

Prelude

At the outset of the American Civil War in 1861, the state of Missouri was a slave state. Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson supported secession, and formed the pro-secession Missouri State Guard, a militia unit. Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon of the Union Army evicted Jackson and the pro-secession portion of the state legislature from the state capital of Jefferson City.[2] The Missouri State Guard won several battles, but Union forces had the secessionists restricted to the southwestern portion of the state by the end of the year. Jackson and the secessionists formed the Confederate government of Missouri, which would function as a government-in-exile for much of its existence, moving from place to place before settling in Marshall, Texas; Missouri now had two competing governments.[3][4] The Union gained control of Missouri in March 1862 after the Battle of Pea Ridge,[5] and the state was then plagued by guerrilla warfare throughout 1862 and 1863.[6]

Price's Raid

By the beginning of September 1864, events east of the Mississippi River, especially the Confederate defeat in the Atlanta campaign, gave Abraham Lincoln, who supported continuing the war, an edge in the 1864 United States Presidential Election over George B. McClellan, who promoted a war-ending armistice that would preserve slavery.[7] Meanwhile, in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Confederates had defeated Union attackers in the Red River campaign in Louisiana in March through May. As events east of the Mississippi turned against the Confederates, General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, was ordered to transfer the infantry under his command to the fighting in the Eastern and Western Theaters. However, this proved to be impossible, as the Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River, preventing a large scale crossing.[8]

Despite having limited resources for an offensive, Smith decided that an attack designed to divert Union troops from the principal theaters of combat would have the same effect as the proposed transfer of troops. Major General Sterling Price and the Confederate Governor of Missouri Thomas Caute Reynolds suggested that an invasion of Missouri would be an effective offensive; Smith approved the plan and appointed Price to command the offensive.[8] Price was a former governor of Missouri, had served in the Mexican-American War, and had commanded the Missouri State Guard in 1861 before entering Confederate service.[9] Price expected that the campaign would create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri, divert Union troops away from principal theaters of combat (many of the Union troops previously defending Missouri had been transferred out of the state, leaving the Missouri State Militia as the state's primary defensive force), and aid McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln.[8] On September 19, Price's column of about 12,000 to 13,000 men entered the state.[10]

Price soon learned that a Union force held Fort Davidson near Pilot Knob. Not wanting to leave a large Union force in the rear of his army, Price decided to attack the Union post. The attack, known as the Battle of Fort Davidson, occurred on September 27, and the Confederates were repulsed with heavy losses. While the fort's defenders retreated that night, Price decided to abandon plans to capture St. Louis as his troops had suffered at least 800 casualties and their morale had been dented.[11] After giving up the proposed St. Louis thrust, Price's army headed for Jefferson City, although the Confederates were slowed by bringing along a large supply train.[12] On October 7, the Confederates approached Jefferson City, which was held by about 7,000 men, mostly inexperienced militia. Faulty Confederate intelligence placed Union strength at 15,000, and Price, fearing another defeat like Fort Davidson, decided not to attack the city, and began moving his army towards Boonville the next day.[13] Boonville was in the pro-Confederate region of Little Dixie in central Missouri, and according to different sources Price was able to recruit around either 1,200[14] or 2,500 men.[15] Price, needing weapons and supplies,[16] then authorized two raids away from his main body of troops: Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr. was sent to Glasgow,[17] and Missouri State Guard Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson's[1] brigade of Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby's division to Sedalia.[17]

Battle

The particular allure of Sedalia for Price was a rumor that the Union army had thousands of mules and cattle in the town, which would be helpful in feeding and remounting the Confederate force.[18] Thompson's command consisted of Shelby's Iron Brigade made up of Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion, Elliott's Missouri Cavalry Regiment, the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment, and Collins' Missouri Battery;[19] the force totaled around 1,200[20] or 1,500 men.[21] While Thompson's command had a nominal strength of about 2,000 men, many of the unit's soldiers were absent visiting their homes in the Boonslick area.[20][22] Slayback's battalion had been performing scouting duties and rejoined Thompson's command at Longwood. The unit reported that Union cavalry were operating in the area but had moved towards the west.[23]

Continuing their movement the next day, the Confederate soldiers captured two Union stragglers near Georgetown who claimed to be former Confederates forced into Union service. The prisoners identified the Union cavalry sighted by Slayback as Brigadier General John B. Sanborn's command, and informed Thompson that Union forces were concentrating at Jefferson City and Kansas City, in addition to a Union infantry force at California that was preparing to head to Georgetown.[23] Thompson, who had established a chain of relay couriers along his path,[22] sent a message to Price to inform him of this development.[24] Thompson initially decided to call off the attack on Sedalia, before changing his mind in the belief that the Union infantry was not heading in his direction and that Sanborn was too far away to interfere.[23]

Sedalia was located in the middle of an expansive prairie with few trees or other features to provide cover to an attacking force.[25] Two redoubts and some rifle pits existed as defensive positions.[19] The town was held by almost 800 home guard and Enrolled Missouri Militia,[25] including men of the 1st Missouri State Militia Cavalry Regiment.[26] Additionally, 33 men of the 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry Regiment under the command of Captain Oscar B. Queen were in the town to meet a wagon train of ammunition coming from Georgetown.[25][26][27] Colonel John D. Crawford of the 40th Enrolled Missouri Militia commanded the garrison.[25]

Thompson believed that surprise gave him the greatest chance of success[25] and attacked before daylight on October 15.[19] Benjamin F. Elliott's regiment, which was largely dressed in captured Union uniforms, led the advance and reached within pistol shot of the Union pickets before being discovered. The Union pickets were scattered and driven back into town. Crawford and many of the Enrolled Missouri Militia soldiers followed them in their flight.[25][28] Queen claimed that Crawford had ordered his men to retreat as soon as Thompson's men were sighted.[27] However, the men of the 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry held, and the Union soldiers were able to form a point of resistance. Elliott's regiment had gotten ahead of the rest of the Confederate force and fell back after meeting the unexpected resistance.[25] Within ten minutes, the rest of Thompson's brigade, including the artillery, arrived. Confederate artillery fire scattered the remaining Enrolled Missouri Militia soldiers, and the men of the 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry surrendered the town.[29] Thompson reported that the Confederates were unaware that the defenders had fled, as they had left their flags flying above the fortifications.[26] Confederate soldiers chased the militiamen as they fled across the prairie, inflicting an unknown number of casualties.[30]

Aftermath

Some degree of plundering occurred after the fighting ended. The historian Paul B. Jenkins, writing in 1906, stated that Thompson's men looted Sedalia, with government property being particular targets for destruction,[31] while the historian Paul Kirkman states that Thompson attempted to limit the plundering to military-related supplies.[21] The modern historian Kyle Sinisi stated that Thompson attempted to keep the capture of military property orderly, although things got out of Thompson's control despite the Confederate commander performing actions such as shooting a mule a soldier was riding and spanking some of his men with the flat of his sword. Sinisi states that the looting was primarily restricted to businesses, not private homes.[30] Some eyewitnesses reported seeing Confederates riding barefoot and carrying their boots filled with stolen whiskey.[31] Sedalia's post office was plundered. Thompson claimed that "no outrage or murder was committed"[32] and reported capturing a number of weapons and wagons of "goods suitable for soldiers". Most of the Confederate units that had participated in the fighting became disorganized, and Slayback's Battalion, which was in the best state of organization,[33] performed guard duty after the battle.[34] Thompson captured almost 2,000 mules and cattle.[30]

The Union suffered one man killed and 23 wounded.[35] Several hundred Union soldiers were captured, but Thompson did not have the ability to keep them as prisoners or issue them standard written paroles.[36][32] Treatment of the prisoners varied between how Thompson classified them: a few hundred were classified as home guard and released, while 75 Enrolled Missouri Militia and 47 Missouri State Militia were given nonstandard verbal paroles,[37] including threats if they reneged on the terms. Several Union officers protested that the practice was illegal, but were ignored.[36] Queen considered the paroles to be "worthless" and returned to Jefferson City for further orders.[38] Knowing that they could be trapped by Union forces if they tarried, the Confederates left Sedalia within hours.[39] Thompson moved north to rejoin Price's main body and rejoined it at the Salt Fork River,[40] near Waverly, on October 18.[41]

Clark's raid on Glasgow was also successful. By October 19, the Confederates had reached Lexington, where they fought against a Union force in the Second Battle of Lexington. Two days later, Union Major General James G. Blunt attempted to stop Price at the crossing of the Little Blue River, but was defeated in the enusing battle. After fighting several more actions, Price encountered nearly 20,000 Union soldiers near Kansas City on October 23. The Battle of Westport followed, and Price's 9,000 soldiers were soundly defeated.[42] Price then fell back into Kansas but was defeated in the Battle of Mine Creek on October 25. About 600 Confederate soldiers were captured at Mine Creek. Later that day, Price ordered the destruction of almost all of the cumbersome wagon train.[43] The final major action of the campaign occurred on October 28 near Newtonia, Missouri. In the Second Battle of Newtonia Price was defeated by Blunt; by this point, the Confederate army was disintegrating. Union troops continued pursuing Price until the Confederates reached the Arkansas River on November 8; the Confederates did not stop retreating until they reached Texas[44] towards the end of November 1864.[45] The campaign failed to affect the election, and while part of the XVI Corps was diverted to Missouri, the transfer was only temporary and did not have a major impact on campaigns in other theaters.[46]

References

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ a b Warner 1987, p. xviii.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–21, 23–25.

- ^ Geise 1962, p. 193.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 377–379.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 343.

- ^ a b c Collins 2016, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Sterling Price". National Park Service. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Collins 2016, pp. 37, 39.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 380–382.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 53.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 59.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 125.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 127.

- ^ a b Collins 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 1906, p. 52.

- ^ a b Sinisi 2020, p. 135.

- ^ a b Kirkman 2011, p. 79.

- ^ a b Lause 2016, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Sinisi 2020, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Monnett 1995, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sinisi 2020, p. 136.

- ^ a b c Lause 2016, p. 36.

- ^ a b Official Records 1893, p. 364.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 84, 86.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c Sinisi 2020, p. 137.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1906, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Lause 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Official Records 1893, p. 665.

- ^ McGhee 2008, p. 132.

- ^ "Missouri Civil War Battles". National Park Service. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ a b Collins 2016, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Lause 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Official Records 1893, p. 365.

- ^ Monnett 1995, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Monnett 1995, p. 32.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 382–384.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 187.

Sources

- Collins, Charles D., Jr. (2016). Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-940804-27-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Geise, William R. (October 1962). "Missouri's Confederate Capital in Marshall, Texas". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 66 (2): 193–207. JSTOR 30236239.

- Jenkins, Paul Burrill (1906). The Battle of Westport (PDF). Kansas City, Missouri: Franklin Hudson Publishing Company. OCLC 475778855.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Kirkman, Paul (2011). The Battle of Westport: Missouri's Great Confederate Raid. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-131-8.

- Lause, Mark A. (2016). The Collapse of Price's Raid: The Beginning of the End in Civil War Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-826-22025-7.

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- Monnett, Howard N. (1995) [1964]. Action Before Westport 1864 (Revised ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-413-6.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. (2020) [2015]. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-4151-9.

- United States War Department. (1893). Davis, George B.; Perry, Leslie J.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (eds.). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume XLI, Part I: Reports. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 262466842 – via Internet Archive.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1987) [1959]. Generals in Gray (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3150-3.