Reconstructions of Old Chinese

Although Old Chinese is known from written records beginning around 1200 BC, the logographic script provides much more indirect and partial information about the pronunciation of the language than alphabetic systems used elsewhere. Several authors have produced reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology, beginning with the Swedish sinologist Bernard Karlgren in the 1940s and continuing to the present day. The method introduced by Karlgren is unique, comparing categories implied by ancient rhyming practice and the structure of Chinese characters with descriptions in medieval rhyme dictionaries, though more recent approaches have also incorporated other kinds of evidence.

Although the various notations appear to be very different, they correspond with each other on most points. By the 1970s, it was generally agreed that Old Chinese had fewer points of articulation than Middle Chinese, a set of voiceless sonorants, and labiovelar and labio-laryngeal initials. Since the 1990s, most authors have agreed on a six-vowel system and a re-organized system of liquids. Earlier systems proposed voiced final stops to account for contacts between stop-final syllables and other tones, but many investigators now believe that Old Chinese lacked tonal distinctions, with Middle Chinese tones derived from consonant clusters at the end of the syllable.

Sources of evidence

The major sources for the sounds of Old Chinese, covering most of the lexicon, are the sound system of Middle Chinese (7th century AD), the structure of Chinese characters, and the rhyming patterns of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), dating from the early part of the 1st millennium BC.[1] Several other kinds of evidence are less comprehensive, but provide valuable clues. These include Min dialects, early Chinese transcriptions of foreign names, early loans between Chinese and neighbouring languages, and families of Chinese words that appear to be related.[2]

Middle Chinese

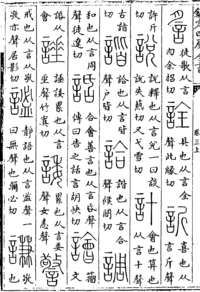

Middle Chinese, or more precisely Early Middle Chinese, is the phonological system of the Qieyun, a rhyme dictionary published in 601, with many revisions and expansions over the following centuries. These dictionaries set out to codify the pronunciations of characters to be used when reading the classics. They indicated pronunciation using the fanqie method, dividing a syllable into an initial consonant and the rest, called the final. In his Qièyùn kǎo (1842), the Cantonese scholar Chen Li performed a systematic analysis of a later redaction of the Qieyun, identifying its initial and final categories, though not the sounds they represented. Scholars have attempted to determine the phonetic content of the various distinctions by comparing them with rhyme tables from the Song dynasty, pronunciations in modern varieties and loans in Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese (the Sinoxenic materials), but many details regarding the finals are still disputed. According to its preface, the Qieyun did not reflect a single contemporary dialect, but incorporated distinctions made in different parts of China at the time (a diasystem).[3][4]

The fact that the Qieyun system contains more distinctions than any single contemporary form of speech means that it retains additional information about the history of the language. The large number of initials and finals are unevenly distributed, suggesting hypotheses about earlier forms of Chinese.[5] For example, it includes 37 initials, but in the early 20th century Huang Kan observed that only 19 of them occurred with a wide range of finals, implying that the others were in some sense secondary developments.[6]

Phonetic series

The logographic Chinese writing system does not use symbols for individual sounds as is done in an alphabetic system.[7] However, the vast majority of characters are phono-semantic compounds, in which a word is written by combining a character for a similarly sounding word with a semantic indicator. Often characters sharing a phonetic element (forming a phonetic series) are still pronounced alike, as in the character 中 (zhōng, 'middle'), which was adapted to write the words chōng ('pour', 沖) and zhōng ('loyal', 忠).[8] In other cases the words in a phonetic series have very different sounds both in Middle Chinese and in modern varieties. Since the sounds are assumed to have been similar at the time the characters were chosen, such relationships give clues to the lost sounds.[9]

The first systematic study of the structure of Chinese characters was Xu Shen's Shuowen Jiezi (100 AD).[10] The Shuowen was mostly based on the small seal script standardized in the Qin dynasty.[11] Earlier characters from oracle bones and Zhou bronze inscriptions often reveal relationships that were obscured in later forms.[12]

Poetic rhyming

Rhyme has been a consistent feature of Chinese poetry. While much old poetry still rhymes in modern varieties of Chinese, Chinese scholars have long noted exceptions. This was attributed to lax rhyming practice of early poets until the late-Ming dynasty scholar Chen Di argued that a former consistency had been obscured by sound change. This implied that the rhyming practice of ancient poets recorded information about their pronunciation. Scholars have studied various bodies of poetry to identify classes of rhyming words at different periods.[13][14]

The oldest such collection is the Shijing, containing songs ranging from the 10th to 7th centuries BC. The systematic study of Old Chinese rhymes began in the 17th century, when Gu Yanwu divided the rhyming words of the Shijing into ten groups (韻部 yùnbù). Gu's analysis was refined by Qing dynasty philologists, steadily increasing the number of rhyme groups. One of these scholars, Duan Yucai, stated the important principle that characters in the same phonetic series would be in the same rhyme group,[a] making it possible to assign almost all words to rhyme groups. A final revision by Wang Li in the 1930s produced the standard set of 31 rhyme groups.[16][17] These were used in all reconstructions up to the 1980s, when Zhengzhang Shangfang, Sergei Starostin and William Baxter independently proposed a more radical splitting into more than 50 rhyme groups.[18][19][20]

Min dialects

The Min dialects are believed to have split off before the Middle Chinese stage, because they contain distinctions that cannot be derived from the Qieyun system. For example, the following dental initials have been identified in reconstructed proto-Min:[21][22]

| Voiceless stops | Voiced stops | Nasals | Laterals | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example word | 單 | 轉 | 炭 | 直 | 長 | 頭 | 南 | 年 | 來 | 老 |

| Proto-Min initial | *t | *-t | *th | *d | *-d | *dh | *n | *nh | *l | *lh |

| Middle Chinese initial | t | th | d | n | l | |||||

Other points of articulation show similar distinctions within stops and nasals. Proto-Min voicing is inferred from the development of Min tones, but the phonetic values of the initials are otherwise uncertain. The sounds indicated as *-t, *-d, etc. are known as "softened stops" due to their reflexes in Jianyang and nearby Min varieties in Fujian, where they appear as fricatives or approximants, or are missing entirely, while the non-softened variants appear as stops. Evidence from early loans into Mienic languages suggests that the softened stops were prenasalized.[23]

Other evidence

Several early texts contain transcriptions of foreign names and terms using Chinese characters for their phonetic values. Of particular importance are the many Buddhist transcriptions of the Eastern Han period, because the native pronunciation of the source languages, such as Sanskrit and Pali, is known in detail.[24][14][25]

Eastern Han commentaries on the classics contain many remarks on the pronunciations of particular words, which has yielded a great deal of information on the pronunciations and even dialectal variation of the period.[26] By studying such glosses, the Qing philologist Qian Daxin discovered that the labio-dental and retroflex stop initials identified in the rhyme table tradition were not present in the Han period.[27][28]

Many students of Chinese have noted "word families", groups of words with related meanings and variant pronunciations, sometimes written using the same character.[29] One common case is "derivation by tone change", in which words in the departing tone appear to be derived from words in other tones.[30] Another alternation involves transitive verbs with an unvoiced initial and passive or stative verbs with a voiced initial, though scholars are divided on which form is basic.[31][32]

In the earliest period, Chinese was spoken in the valley of the Yellow River, surrounded by neighbouring languages, some of whose relatives, particularly Austroasiatic and the Tai–Kadai and Miao–Yao languages, are still spoken today. The earliest borrowings in both directions provide further evidence of Old Chinese sounds, though complicated by uncertainty about the reconstruction of early forms of those languages.[33]

Systems

Many authors have produced their own reconstructions of Old Chinese. A few of the most influential are listed here.

Karlgren (1940–1957)

The first complete reconstruction of Old Chinese was produced by the Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren in a dictionary of Middle and Old Chinese, the Grammata Serica (1940), revised in 1957 as the Grammata Serica Recensa (GSR). Although Karlgren's Old Chinese reconstructions have been superseded, his comprehensive dictionary remains a valuable reference for students of Old Chinese, and characters are routinely identified by their GSR position.[34] Karlgren's remained the most commonly used until it was superseded by the system of Li Fang-Kuei in the 1970s.[35]

In his Études sur la phonologie chinoise (1915–1926), Karlgren produced the first complete reconstruction of Middle Chinese (which he called "Ancient Chinese"). He presented his system as a narrow transcription of the sounds of the standard language of the Tang dynasty. Beginning with his Analytical Dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese (1923), he compared these sounds across groups of words written with Chinese characters with the same phonetic component. Noting that such words were not always pronounced identically in Middle Chinese, he postulated that their initials had a common point of articulation in an earlier phase he called "Archaic Chinese", but which is now usually called Old Chinese. For example, he postulated velar consonants as initials in the series

In rarer cases where different types of initials occurred in the same series, as in

- 各 kâk, 胳 kâk, 格 kak, 絡 lâk, 駱 lâk, 略 ljak

he postulated initial clusters *kl- and *gl-.[37]

Karlgren believed that the voiced initials of Middle Chinese were aspirated, and projected these back onto Old Chinese. He also proposed a series of unaspirated voiced initials to account for other correspondences, but later workers have discarded these in favour of alternative explanations.[38] Karlgren accepted the argument of the Qing philologist Qian Daxin that the Middle Chinese dental and retroflex stop series were not distinguished in Old Chinese, but otherwise proposed the same points of articulation in Old Chinese as in Middle Chinese. This led him to the following series of initial consonants:[39][40]

| Labial | Dental | Sibilant | Supradental | Palatal | Velar | Laryngeal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *tṣ | *t̑ | *k | *· |

| aspirate | *p' | *t' | *ts' | *tṣ' | *t̑' | *k' | ||

| voiced aspirate | *b' | *d' | *dz' | *dẓ' | *d̑' | *g' | ||

| voiced | *(b) | *d | *dz | *d̑ | *g | |||

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ń | *ng | ||||

| Fricative or lateral |

voiceless | *s | *ṣ | *ś | *x | |||

| voiced | *l | *z | ||||||

To account for the broad variety of vowels in his reconstruction of Middle Chinese, Karlgren also proposed a complex inventory of Old Chinese vowels:[41][42]

| *ŭ | *u | |||

| *e | *ĕ | *ə | *ô | *ộ |

| *ɛ | *o | *ǒ | ||

| *a | *ă | *â | *å |

He also had a secondary vowel *i, which occurred only in combination with other vowels. As with Middle Chinese, Karlgren viewed his reconstruction as a narrow transcription of the sounds of Old Chinese. Thus *e rhymed with *ĕ in the Shijing, *a rhymed with *ă and *â, *ɛ rhymed with *ĕ and *ŭ, *ŭ rhymed with *u, *ô rhymed with *ộ, and *o rhymed with *ǒ and *å.[41]

Karlgren projected the final consonants of Middle Chinese, semivowels /j/ and /w/, nasals /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/, and stops /p/, /t/ and /k/ back onto Old Chinese. He also noted many cases where words in the departing tone rhymed or shared a phonetic element with words ending in a stop, e.g.

He suggested that the departing tone words in such pairs had ended with a final voiced stop (*-d or *-ɡ) in Old Chinese.[45] To account for occasional contacts between Middle Chinese finals -j and -n, Karlgren proposed that -j in such pairs derived from Old Chinese *-r.[46] He believed there was insufficient evidence to support definitive statements about Old Chinese tones.[47]

Yakhontov (1959–1965)

In a pair of papers published in 1960, the Russian linguist Sergei Yakhontov proposed two revisions to the structure of Old Chinese that are now widely accepted. He proposed that both the retroflex initials and the division-II vowels of Middle Chinese derived from the Old Chinese medial *-l- that Karlgren had proposed to account for phonetic series contacts with l-.[48] Yakhontov also observed that the Middle Chinese semi-vowel -w- had a limited distribution, occurring either after velar or laryngeal initials or before finals -aj, -an or at. He suggested that -w- had two sources, deriving from either a new series of labio-velar and labio-laryngeal initials, or from the breaking of a vowel *-o- to -wa- before dental codas.[49][50]

| Labial | Dental | Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | |||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | *ʔʷ |

| aspirate | *ph | *th | *tsh | *kh | *khʷ | |||

| voiced aspirate | *bh | *dh | *dzh | *gh | *ghʷ | |||

| voiced | *d | *g | *gʷ | |||||

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ng | *ngʷ | ||||

| Fricative | *s | *x | *xʷ | |||||

| Lateral | *l | |||||||

Yakhontov proposed a simpler seven-vowel system:[53][54]

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | *e | *ü | *ə | *u |

| Open | *ä | *â | *o | |

However these vowels had an uneven distribution, with *ä and *â almost in complementary distribution and *ü occurring only in open syllables and before *-k.[55] His final consonants were the nasals *-m, *-n and *-ng, corresponding stops *-p, *-t and *-k, as well as *-r, which became -j or disappeared in Middle Chinese.[56][54]

Pulleyblank (1962)

The Canadian sinologist Edwin Pulleyblank published a reconstruction of the consonants of Old Chinese in two parts in 1962. In addition to new analyses of the traditional evidence, he also made substantial use of transcription evidence. Though not a full reconstruction, Pulleyblank's work has been very influential, and many of his proposals are now widely accepted.

Pulleyblank adapted Dong Tonghe's proposal of a voiceless counterpart to the initial *m, proposing a full set of aspirated nasals,[57] as well as Yakhontov's labio-velar and labio-laryngeal initials.[58]

Pulleyblank also accepted Yakhontov's expanded role for the medial *-l-, which he noted was cognate with Tibeto-Burman *-r-.[59] To account for phonetic contacts between Middle Chinese l- and dental initials, he also proposed an aspirated lateral *lh-.[60] Pulleyblank also distinguished two sets of dental series, one derived from Old Chinese dental stops and the other derived from dental fricatives *δ and *θ, cognate with Tibeto-Burman *l-.[61] He considered recasting his Old Chinese *l and *δ as *r and *l to match the Tibeto-Burman cognates, but rejected the idea to avoid complicating his account of the evolution of Chinese.[62] Later he re-visited this decision, recasting *δ, *θ, *l and *lh as *l, *hl, *r and *hr respectively.[63]

Pulleyblank also proposed an Old Chinese labial fricative *v for the few words where Karlgren had *b, as well as a voiceless counterpart *f.[64] Unlike the above ideas, these have not been adopted by later workers.

| Labial | Dental | Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | |||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kw | *ʔ[c] | *ʔw |

| aspirate | *ph | *th | *tsh | *kh | *khw | |||

| voiced | *b | *d | *dz | *g | *gw | |||

| Nasal | aspirate | *mh | *nh | *ŋh | *ŋhw | |||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ŋ | *ŋw | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | *f | *θ | *s | *h | *hw | ||

| voiced | *v | *δ | *ɦ | *ɦw | ||||

| Lateral | aspirate | *lh | ||||||

| voiced | *l | |||||||

Pulleyblank also proposed a number of initial consonant clusters, allowing any initial to be preceded by *s- and followed by *-l- (*-r- in later revisions), and grave initials and *n to be followed by *-δ- (*-l- in later revisions).[65]

On the basis of transcription evidence, Pulleyblank argued that the -j- medial of Middle Chinese was an innovation not present in Old Chinese. He classified Middle Chinese finals without -j- as type A and those with the medial as type B, and suggested that they arose from Old Chinese short and long vowels respectively.[66]

André-Georges Haudricourt had demonstrated in 1954 that the tones of Vietnamese were derived from final consonants *-ʔ and *-s in an atonal ancestral language.[67] He also suggested that the Chinese departing tone derived from earlier *-s, which acted as a derivational suffix in Old Chinese. Then the departing tone syllables that Karlgren had reconstructed with *-d and *-g could instead be reconstructed as *-ts and *-ks, with the stops subsequently being lost before the final *-s, which eventually became a tonal distinction.[68] The absence of a corresponding labial final could be attributed to early assimilation of *-ps to *-ts. Pulleyblank strengthened the theory with several examples of syllables in the departing tone being used to transcribe foreign words ending in -s into Chinese.[69][70] He further proposed that the Middle Chinese rising tone derived from *-ʔ, implying that Old Chinese lacked tones.[71] Mei Tsu-lin later supported this theory with evidence from early transcriptions of Sanskrit words, and pointed out that rising tone words end in a glottal stop in some modern Chinese dialects, including Wenzhounese and some Min dialects.[72]

Li (1971)

The Chinese linguist Li Fang-Kuei published an important new reconstruction in 1971, synthesizing proposals of Yakhontov and Pulleyblank with ideas of his own. His system remained the most commonly used until it was replaced by that of Baxter in the 1990s. Although Li did not produce a complete dictionary of Old Chinese, he presented his methods in sufficient detail that others could apply them to the data.[73] Schuessler (1987) includes reconstructions of the Western Zhou lexicon using Li's system.[35]

Li included the labio-velars, labio-laryngeals and voiceless nasals proposed by Pulleyblank. As Middle Chinese g- occurs only in palatal environments, Li attempted to derive both g- and ɣ- from Old Chinese *g- (and similarly *gw-), but had to assume irregular developments in some cases.[74][75] Thus he arrived at the following inventory of initial consonants:[76][77]

| Labial | Dental | Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | |||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kw | *ʔ[d] | *ʔw |

| aspirate | *ph | *th | *tsh | *kh | *kwh | |||

| voiced | *b | *d | *dz | *g | *gw | |||

| Nasal | voiceless | *hm | *hn | *hng | *hngw | |||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ng | *ngw | ||||

| Lateral | voiceless | *hl | ||||||

| voiced | *l | |||||||

| Fricative or approximant |

voiceless | *s | *h | *hw | ||||

| voiced | *r | |||||||

Li also included the *-l- medial proposed by Pulleyblank, in most cases re-interpreting it as *-r-. In addition to the medial *-j- projected back from Middle Chinese, he also postulated the combination *-rj-.[78]

Assuming that rhyming syllables had the same main vowel, Li proposed a system of four vowels *i, *u, *ə and *a. He also included three diphthongs *iə, *ia and *ua to account for syllables that were placed in rhyme groups reconstructed with *ə or *a but were distinguished in Middle Chinese:[79]

| *i | *u | |

| *iə | *ə | |

| *ia | *a | *ua |

Li followed Karlgren in proposing final consonants *-d and *-g, but was unable to clearly separate them from open syllables, and extended them to all rhyme groups but one, for which he proposed a final *-r.[80] He also proposed that labio-velar consonants could occur as final consonants. Thus in Li's system every syllable ended in one of the following consonants:[81]

| *p | *m | ||

| *r | *d | *t | *n |

| *g | *k | *ng | |

| *gw | *kw | *ngw |

Li marked the rising and departing tones with a suffix *-x or *-h, without specifying how they were realized.[82]

Baxter (1992)

William H. Baxter's monograph A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology displaced Li's reconstruction in the 1990s. Baxter did not produce a dictionary of reconstructions, but the book contains a large number of examples, including all the words occurring in rhymes in the Shijing, and his methods are described in great detail. Schuessler (2007) contains reconstructions of the entire Old Chinese lexicon using a simplified version of Baxter's system.

Baxter's treatment of the initials is largely similar to the proposals of Pulleyblank and Li. He reconstructed the liquids *l, *hl, *r and *hr in the same contexts as Pulleyblank.[83] Unlike Li, he distinguished Old Chinese *ɦ and *w from *g and *gʷ.[75] Other additions were *z, with a limited distribution,[84] and voiceless and voiced palatals *hj and *j, which he described as "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".[85]

| Labial | Dental | Palatal [e] |

Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | ||||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | *ʔʷ | |

| aspirate | *ph | *th | *tsh | *kh | *kʷh | ||||

| voiced | *b | *d | *dz | *g | *gʷ | ||||

| Nasal | voiceless | *hm | *hn | *hng | *hngʷ | ||||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ng | *ngʷ | |||||

| Lateral | voiceless | *hl | |||||||

| voiced | *l | ||||||||

| Fricative or approximant |

voiceless | *hr | *s | *hj | *x | *hw | |||

| voiced | *r | *z | *j | *ɦ | *w | ||||

As in Pulleyblank and Li's systems, the possible medials were *-r-, *-j- and the combination *-rj-.[88] However while Li had proposed *-rj- as conditioning palatalization of velars, Baxter followed Pulleyblank in proposing it as the source of division III chóngniǔ finals.[89]

Baxter's major contribution concerned the vowel system and rhyme groups. Nicholas Bodman had proposed a six-vowel system for a proto-Chinese phase, based on comparison with other Sino-Tibetan languages.[90] Baxter argued for a six-vowel system in Old Chinese by re-analysing of the traditional rhyme groups. For example, the traditional 元 rhyme group of the Shijing corresponds to three different finals in Middle Chinese. While Li had sought to reconcile these distinct outcomes from rhyming words by reconstructing the finals as *-ian, *-an and *-uan, Baxter argued that in fact they did not rhyme in the Shijing, and could thus be reconstructed with three distinct vowels, *e, *a and *o. Baxter proposed that the traditional 31 rhyme groups should be refined to over 50, and performed a statistical analysis of the actual rhymes of the Shijing, which supported the new groups with varying degrees of confidence.[91]

| *i | *ɨ | *u |

| *e | *a | *o |

Zhengzhang Shangfang and Sergei Starostin independently developed similar vowel systems.[18][19]

Baxter's final consonants were those of Middle Chinese, plus *-wk (an allophone of *-kʷ), optionally followed by a post-coda *-ʔ or *-s.[93]

| MC vocalic coda | MC stop coda | MC nasal coda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 平 | 上 | 去 | 入 | 平 | 上 | 去 | |

| *-p | *-m | *-mʔ | *-ms | ||||

| *-j | *-jʔ | *-js | *-ts | *-t | *-n | *-nʔ | *-ns |

| *-∅ | *-ʔ | *-s | *-ks | *-k | *-ŋ | *-ŋʔ | *-ŋs |

| *-w | *-wʔ | *-ws | *-wks | *-wk | |||

Baxter also speculated on the possibility of a glottal stop occurring after oral stop finals. The evidence is limited, and consists mainly of contacts between rising tone syllables and -k finals, which could alternatively be explained as phonetic similarity.[94]

Zhengzhang (1981–1995)

Zhengzhang Shangfang published his ideas in a series of articles in Chinese provincial journals, which were not widely disseminated. Some of his notes were translated into English by Laurent Sagart in 2000.[95] He published a monograph in 2003.[96]

Zhengzhang's reconstruction incorporates a suggestion by Pan Wuyun that the three Middle Chinese laryngeal initials are reflexes of uvular stops in Old Chinese, and thus parallel to the other sets of stops.[97] He argues that Old Chinese lacked affricate initials, and that the Middle Chinese affricates reflect Old Chinese clusters of *s- and other consonants, yielding the following inventory of initial consonants:[98]

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | *p | *t | *k | *q > *ʔ | |

| aspirate | *ph | *th | *kh | *qh > *h | ||

| voiced | *b | *d | *g | *ɢ > *ɦ | ||

| Nasal | aspirate | *mh | *nh | *ŋh | ||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ŋ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | *s | ||||

| Lateral | aspirate | *lh | ||||

| voiced | *l | |||||

| Approximant | aspirate | *rh | ||||

| voiced | *w | *r | *j | |||

Zhengzhang's *w medial could occur only after velar and uvular initials, matching the labio-velar and labio-laryngeal initials of other reconstructions.[99] Instead of marking type B syllables with a *-j- medial, he treated type A syllables as having long vowels.[100]

Zhengzhang also refined the traditional rhyme classes to obtain a six-vowel system similar to those of Baxter and Starostin, but with *ɯ corresponding to Baxter's *ɨ and Starostin's *ə:[101]

| *i | *ɯ | *u |

| *e | *a | *o |

Zhengzhang argued that the final stops of Old Chinese were voiced, like those of Old Tibetan.[102] He accepted the consonantal origin of Middle Chinese tones.[103]

Baxter–Sagart (2014)

Jerry Norman concluded his review of Baxter (1992) with the words:

A reader of Baxter's book is left with the impression that he has pushed the traditional approach to its limits and that any further progress in the field will have to be based on a quite different methodological approach.[104]

Baxter has attempted a new approach in collaboration with Laurent Sagart, who had used a variant of Baxter's system in a study of the derivational morphology of Old Chinese.[105] They used additional evidence, including word relationships deduced from these morphology theories, Norman's reconstruction of Proto-Min, divergent Chinese varieties such as Waxiang, early loans to other languages, and character forms in recently unearthed documents.[106] They also sought to apply the hypothetico-deductive method to linguistic reconstruction: instead of insisting on deducing patterns from data, they proposed hypotheses to be tested against data.[107]

Baxter and Sagart retained the six-vowel system, though re-casting *ɨ as *ə. The finals consonants were unchanged except for the addition of a final *r in syllables showing connections between final consonants -j and -n in Middle Chinese, as suggested by Sergei Starostin.[108]

Initials

The initial consonants of the revised system largely correspond to those of Baxter (1992) apart from the dropping of the marginal initials *z, *j and *hj.[109] Instead of marking type B syllables with a *-j- medial, they treated type A syllables as having pharyngealized initials, adapting a proposal of Jerry Norman, and thus doubled the number of initials.[110][f] They also adopted the proposal of Pan Wuyun to recast the laryngeal initials as uvular stops, though they retained a separate glottal stop.[112]

| Labial | Dental | Velar | Uvular | Laryngeal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | |||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p, *pˤ | *t, *tˤ | *ts, *tsˤ | *k, *kˤ | *kʷ, *kʷˤ | *q, *qˤ | *qʷ, *qʷˤ | *ʔ, *ʔˤ | (*ʔʷˤ) |

| aspirate | *pʰ, *pʰˤ | *tʰ, *tʰˤ | *tsʰ, *tsʰˤ | *kʰ, *kʰˤ | *kʷʰ, *kʷʰˤ | *qʰ, *qʰˤ | *qʰʷ, *qʰʷˤ | |||

| voiced | *b, *bˤ | *d, *dˤ | *dz, *dzˤ | *ɡ, *ɡˤ | *ɡʷ, *ɡʷˤ | *ɢ, *ɢˤ | *ɢʷ, *ɢʷˤ | |||

| Nasal | voiceless | *m̥, *m̥ˤ | *n̥, *n̥ˤ | *ŋ̊, *ŋ̊ˤ | *ŋ̊ʷ, *ŋ̊ʷˤ | |||||

| voiced | *m, *mˤ | *n, *nˤ | *ŋ, *ŋˤ | *ŋʷ, *ŋʷˤ | ||||||

| Lateral | voiceless | *l̥, *l̥ˤ | ||||||||

| voiced | *l, *lˤ | |||||||||

| Fricative or approximant |

voiceless | *r̥, *r̥ˤ | *s, *sˤ | |||||||

| voiced | *r, *rˤ | |||||||||

They propose uvular initials as a second source of the Middle Chinese palatal initial in addition to *l, so that series linking Middle Chinese y- with velars or laryngeals instead of dentals are reconstructed as uvulars rather than laterals, for example[112]

| Middle Chinese |

Old Chinese | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baxter (1992) | Baxter–Sagart | ||

| 舉 | kjoX | *kljaʔ | *k.q(r)aʔ > *[k](r)aʔ |

| 與 | yoX | *ljaʔ | *m.q(r)aʔ > *ɢ(r)aʔ |

Baxter and Sagart concede that it is typologically unusual for a language to have as many pharyngealized consonants as nonpharyngealized ones, and suggest that this situation may have been short-lived.[113] Drawing on Starostin's observation of a correlation between A/B syllables in Chinese and long/short vowels in Mizo cognates, as well as typological parallels in Austroasiatic and Austronesian, they propose that pharyngealized *CˤV(C) < *CʕV(C) type-A syllables developed from Proto-Sino-Tibetan **CVʕV(C) disyllables in which the two vowels were identical, that is, a geminate vowel split by a voiced pharyngeal fricative.[114]

Root structure

The major departure from Baxter's system lay in the structure of roots proposed by Sagart, in which roots could comprise either a monosyllable or a syllable preceded by a preinitial consonant, in one of two patterns:[115]

- a "tightly attached" preinitial forming a consonant cluster, as in 肉 *k.nuk "flesh", 用 *m.loŋ-s "use" and 四 *s.lij-s "four", and

- a "loosely attached" preinitial, forming a minor syllable, as in 脰 *kə.dˤok-s "neck", 舌 *mə.lat "tongue" and 脣 *sə.dur "lip".

Similar root structures are found in the modern rGyalrong, Khmer and Atayal languages.[116] Sagart argued that such iambic combinations, like single syllables, were written with single characters and also counted as a single foot in verse.[117] Rarely, the minor syllables received a separate character, explaining a few puzzling examples of 不 *pə- and 無 *mə- used in non-negative sentences.[118]

Under the Baxter-Sagart system, these consonant prefixes form a part of the Old Chinese derivational morphology. For example, they propose nasal prefixes *N- (detransitiviser) and *m- (agentive, among other functions) as a source of the initial voicing alterations in Middle Chinese; both also have cognates in Tibeto-Burman.[119]

The various initials are reconstructed based on comparisons with proto-Min cognates and early loans to Hmong–Mien languages and Vietnamese:[120]

| Middle Chinese | proto-Min | proto-Hmong–Mien | Vietnamese | Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese[g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ph | *ph | *pʰ | ph H | *pʰ[121] |

| ? | *mp | ? | *mə.pʰ[122] | |

| p | *p | *p | b H | *p[123] |

| ? | v H | *C.p[124] | ||

| *-p | *mp | ? | *mə.p,[125] *Nə.p[126] | |

| b | *bh | ? | v H,L | *m.p[127] |

| *mb | ? | *m.b,[128] *C.b[129] | ||

| *b | *b | b L | *b[130] | |

| ? | b H,L | *N.p[131] | ||

| *-b | *mb | v L | *mə.b,[132] *Cə.b[133] | |

| m | *mh | *hm | m H | *C.m[134] |

| *m | *m | m L | *m[135] | |

| x(w) | *x | ? | ? | *m̥[136] |

Comparison

The different reconstructions provide different interpretations of the relationships between the categories of Middle Chinese and the main bodies of ancient evidence: the phonetic series (used to reconstruct initials), and the Shijing rhyme groups (used to reconstruct finals).

Initials

Karlgren first stated the principle that words written with the same phonetic component had initials with a common point of articulation in Old Chinese. Moreover, nasal initials seldom interchanged with other consonants.[137] Thus phonetic series can be placed into classes, depending on the range of Middle Chinese initials found in them, and these classes are presumed to correspond to classes of Old Chinese initials.[138] Where markedly different Middle Chinese initials occur together in a series, investigators have proposed additional consonants, or clusters of consonants, in Old Chinese.

| Type of series | Middle Chinese | Examples | Old Chinese reconstructions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li | Baxter | Karlgren | Pulleyblank | Li | Baxter | |||||

| Labial stops[139] | 幫 | p- | p- | 彼 陂 | 稟 禀 | 方 枋 | *p- | *p- | *p- | *p- |

| 滂 | ph- | ph- | 被 披 | 雱 妨 | *p'- | *ph- | *ph- | *ph- | ||

| 並 | b- | b- | 皮 被 | 彷 旁 | *b'- | *b- | *b- | *b- | ||

| 來 | l- | l- | 稟 廩 | *bl- | *vl- | *bl- | *b-r- | |||

| Labial nasal[140] | 明 | m- | m- | 勿 物 | 亡 忙 | 母 每 | *m- | *m- | *m- | *m- |

| 曉 | x(w)- | x(w)- | 芴 忽 | 衁 巟 | 悔 海 | *xm- | *mh- | *hm- | *hm- | |

| Dental stops, retroflex stops and palatals[141] |

端 | t- | t- | 睹 都 | 當 黨 | 等 | *t- | *t- | *t- | *t- |

| 透 | th- | th- | 攩 鏜 | *t'- | *th- | *th- | *th- | |||

| 定 | d- | d- | 屠 瘏 | 堂 棠 | 待 特 | *d'- | *d- | *d- | *d- | |

| 知 | ṭ- | tr- | 褚 著 | *t- | *tl- | *tr- | *tr- | |||

| 徹 | ṭh- | trh- | 躇 | 瞠 | 祉 | *t'- | *thl- | *thr- | *thr- | |

| 澄 | ḍ- | dr- | 著 | 𣥺 | 持 | *d- | *dl- | *dr- | *dr- | |

| 章 | tś- | tsy- | 者 渚 | 掌 | 止 趾 | *t̑i̯- | *t-[h] | *tj- | *tj- | |

| 昌 | tśh- | tsyh- | 惝 敞 | 齒 | *t̑'i̯- | *th-[h] | *thj- | *thj- | ||

| 禪 | dź- | dzy- | 署 | 尚 裳 | 侍 時 | *d̑i̯- | *d-[h] | *dj- | *dj- | |

| 書 | ś- | sy- | 奢 暑 | 賞 | 詩 | *śi̯- | ? | *sthj- | *stj- | |

| Dental stops, s- and j-[142] |

透 | th- | th- | 稌 | 胎 | *t'- | *θ- | *th- | *hl- | |

| 定 | d- | d- | 涂 途 | 盾 遁 | 殆 迨 | *d'- | *δ- | *d- | *l- | |

| 徹 | ṭh- | trh- | 輴 | *t'- | *θl- | *thr- | *hlr- | |||

| 澄 | ḍ- | dr- | 除 除 | 治 | *di̯- | *δl- | *dr- | *lr- | ||

| 心 | s- | s- | 枲 | *s- | *sθ- | *st- | *sl- | |||

| 邪 | z- | z- | 敘 徐 | 循 | 鈶 耜 | *dzi̯- | *sδy- | *rj- | *zl- | |

| 書 | ś- | sy- | 賖 | 始 | *śi̯- | *θ-[h] | *sthj- | *hlj- | ||

| 船 | ź- | zy- | 楯 | *d'i̯- | *δ-[h] | *dj- | *Lj- | |||

| 以 | ji- | y- | 余 餘 | 㠯 台 | *di̯-, *zi̯- | *δ-[h] | *r- | *lj- | ||

| Dental stops and l-[143] | 來 | l- | l- | 離 | 剌 賴 | 禮 | *l- | *l- | *l- | *C-r- |

| 透 | th- | th- | 獺 | 體 | *t'l- | *lh- | *hl- | *hr- | ||

| 徹 | ṭh- | trh- | 离 魑 | *t'l- | *lh- | *hlj- | *hrj- | |||

| Dental nasal[144] | 泥 | n- | n- | 怒 奴 | 餒 | *n- | *n- | *n- | *n- | |

| 娘 | ṇ- | nr- | 女 拏 | 諉 | 狃 紐 | *ni̯- | *nl- | *nr- | *nr- | |

| 日 | ńź- | ny- | 如 汝 | 緌 | *ńi̯- | *nj- | *nj- | *nj- | ||

| 透 | th- | th- | 妥 | *t'n- | *nh- | *hn- | *hn- | |||

| 徹 | ṭh- | trh- | 丑 | *t'n- | *nhl- | *hnr- | *hnr- | |||

| 書 | ś- | sy- | 恕 | *śńi̯- | *nh-[h] | *hnj- | *hnj- | |||

| 心 | s- | s- | 絮 | 綏 | 羞 | *sni̯- | *snh- | *sn- | *sn- | |

| Sibilants[145] | 精 | ts- | ts- | 佐 嗟 | 借 | 精 | *ts- | *ts- | *ts- | *ts- |

| 清 | tsh- | tsh- | 差 瑳 | 鵲 錯 | 青 請 | *ts'- | *tsh- | *tsh- | *tsh- | |

| 從 | dz- | dz- | 鹺 | 籍 藉 | 請 情 | *dz'- | *dz- | *dz- | *dz- | |

| 心 | s- | s- | 昔 惜 | 姓 性 | *s- | *s- | *s- | *s- | ||

| 莊 | tṣ- | tsr- | 斮 | *tṣ- | *tsl- | *tsr- | *tsr- | |||

| 初 | tṣh- | tsrh- | 差 差 | *tṣ'- | *tshl- | *tshr- | *tshr- | |||

| 崇 | dẓ- | dzr- | 槎 | *dẓ'- | *dzl- | *dzr- | *dzr- | |||

| 生 | ṣ- | sr- | 生 甥 | *s- | *sl- | *sr- | *srj- | |||

| Velars and palatals[146] | 見 | k- | k- | 車 | 稽 | 監 | *k- | *k- | *k- | *k- |

| 溪 | kh- | kh- | 庫 | 稽 | *k'- | *kh- | *kh- | *kh- | ||

| 匣 | ɣ- | h- | 檻 | *g'- | *g- | *g- | *g- | |||

| 群 | g- | g- | 耆 鰭 | *g'i̯- | *gy- | *gj- | *gj- | |||

| 章 | tś- | tsy- | 旨 指 | *t̑i̯- | *ky- | *krj- | *kj- | |||

| 昌 | tśh- | tsyh- | 車 | *t̑'i̯- | *khy- | *khrj- | *khj- | |||

| 禪 | dź- | dzy- | 嗜 | *d̑i̯- | *gy- | *grj- | *gj- | |||

| 來 | l- | l- | 黎 | 藍 籃 | *gl- | *ɦl- | *gl- | *g-r- | ||

| Laryngeals[147] | 影 | ʔ- | ʔ- | 焉 | 音 愔 | *·- | *ʔ- | *ʔ- | *ʔ- | |

| 曉 | x- | x- | 呼 呼 | 歆 | *x- | *x- | *x- | *x- | ||

| 匣 | ɣ- | h- | 乎 | *g'- | *ɦ- | *g- | *ɦ- | |||

| 云 | j- | hj- | 焉 | *gi̯- | *ɦ-[h] | *gj- | *ɦj- | |||

| Velar nasal[148] | 疑 | ng- | ng- | 我 餓 | 倪 掜 | 堯 僥 | *ng- | *ŋ- | *ng- | *ng- |

| 曉 | x- | x- | 羲 犧 | 鬩 | 曉 膮 | *x- | *ŋh- | *hng- | *hng- | |

| 日 | ńź- | ny- | 兒 唲 | 繞 襓 | *ńi̯- | *ŋy- | *ngrj- | *ngj- | ||

| 書 | ś- | sy- | 燒 | *śńi̯- | *ŋhy- | *hngrj- | *hngj- | |||

| Velars with -w-[149] | 見 | kw- | kw- | 刮 | 季 | 九 軌 | *kw- | *kw- | *kw- | *kʷ- |

| 溪 | khw- | khw- | 闊 | *k'w- | *khw- | *khw- | *kʷh- | |||

| 匣 | ɣw- | hw- | 話 | *g'w- | *gw- | *gw- | *gʷ- | |||

| 群 | gw- | gw- | 悸 | 頄 仇 | *g'wi̯- | gwy- | *gwj- | *gʷj- | ||

| Laryngeals with -w-[150] | 影 | ʔw- | ʔw- | 汙 迂 | 郁 | *ʔw- | *ʔw- | *ʔw- | *ʔʷ- | |

| 曉 | xw- | xw- | 吁 訏 | 諼 | 賄 | *xw- | *xw- | *xw- | *hw- | |

| 匣 | ɣw- | hw- | 緩 | *g'w- | *ɦw- | *gw- | *w- | |||

| 云 | jw- | hwj- | 于 宇 | 爰 猨 | 有 洧 | *gi̯w- | *ɦw-[h] | *gwj- | *wj- | |

| Velar nasal with -w-[151] | 疑 | ngw- | ngw- | 吪 訛 | *ngw- | *ŋw- | *ngw- | *ngʷ- | ||

| 曉 | xw- | xw- | 化 貨 | *xw- | *ŋhw- | *hngw- | *hngʷ- | |||

Medials

Middle Chinese is usually reconstructed with two medials:

- -w- in Qieyun syllables classified as "closed" (合 hé) in the Song dynasty rhyme tables, in contrast to "open" (開 kāi) syllables,[152] and

- -j- in syllables with division-III (or Type B) finals.

Karlgren projected both of these medials back to Old Chinese. However, since the work of Yakhontov most reconstructions have omitted a *w medial but included labiovelar and labiolaryngeal initials.[153][154][92] Most reconstructions since Pulleyblank have included a medial *r, but the *j medial has become more controversial.

Middle Chinese "divisions"

Karlgren noted that the finals of Middle Chinese can be divided into a number of classes, which combine with different groups of initials. These distributional classes are partially aligned with the placement of finals in different rows of the Song dynasty rhyme tables. As three classes of final occurred in the first, second and fourth rows respectively, he named them finals of divisions I, II and IV. The remaining finals he called "division-III finals" because they occurred in the third row of the tables. Some of these (the "pure" or "independent" division-III finals) occurred only in that row, while others (the "mixed" finals) could also occur in the second or fourth rows with some initials.[155] Karlgren disregarded the chongniu distinction, but later workers have emphasized its importance. Li Rong, in a systematic comparison of the rhyme tables with a recently discovered early edition of the Qieyun, identified seven classes of finals. The table below lists the combinations of initial and final classes that occur in the Qieyun, with the row of the rime tables in which each combination was placed:[156][157]

| Phonetic series | Middle Chinese initials | Middle Chinese finals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| div. I | div. II | division-III | div. IV | |||||

| pure | mixed | chongniu | ||||||

| Labials | Labials | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Dentals | Dental stops | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Retroflex stops | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Dentals, velars | Palatal sibilants | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Sibilants | Dental sibilants | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Retroflex sibilants | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Velars | Velars | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Laryngeals | Laryngeals | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

On the basis of these combinations, the initials of Old and Middle Chinese can be divided into two broad types: grave initials (labials, velars and laryngeals), which combine with all types of finals, and acute initials (dentals and sibilants), with more restricted distribution.[158]

Karlgren derived the four divisions of Middle Chinese finals from the palatal medial and a range of Old Chinese vowels. More recent reconstructions derive division II from an Old Chinese medial *r (given as *l in the early work of Yakhontov and Pulleyblank). This segment also accounts for phonetic series contacts between stops and l-, retroflex initials and (in some later work) the chongniu distinction.[159] Division III finals are generally held to represent a palatal element, at least in Middle Chinese. Division I and IV finals have identical distributions in the rhyme dictionaries.[160] These two classes are believed to be primary, while the others were modified by medials.[161]

Type A and B syllables

A fundamental distinction within Middle Chinese is between division-III finals and the rest. Most scholars believe that division-III finals were characterized by a palatal medial -j- in Middle Chinese. Karlgren projected this medial back to a medial *-j- in Old Chinese (*-i̯- in Karlgren's notation), a position followed by most reconstructions up to the 1990s, including those of Li and Baxter.[162]

Other authors have suggested that the Middle Chinese medial was a secondary development not present in Old Chinese. Evidence includes the use of syllables with division-III finals to transcribe foreign words lacking any such medial, the lack of the medial in Tibeto-Burman cognates and modern Min reflexes, and the fact that it is ignored in phonetic series.[163][164][165] However, it is generally agreed that syllables with division-III finals and other syllables, labelled types B and A respectively by Pulleyblank, were distinguished in Old Chinese, though scholars differ on how this distinction was realized.

Many realizations of the distinction have been proposed.[166][167] Starostin and Zhengzhang proposed that type A syllables were distinguished by longer vowels,[168][169] the reverse of an earlier proposal by Pulleyblank.[170][171] Norman suggested that type B syllables (his class C), which comprised over half of the syllables of the Qieyun, were in fact unmarked in Old Chinese. Instead, he proposed that the remaining syllables were marked by retroflexion (the *-r- medial) or pharyngealization, either of which prevented palatalization in Middle Chinese.[111] Baxter and Sagart adopted a variant of this proposal, reconstructing pharyngealized initials in all type A syllables.[110] The different realizations of the type A/B distinction are illustrated by the following reconstructions of Middle Chinese finals from one of the traditional Old Chinese rhyme groups:

| Middle Chinese | Old Chinese reconstructions | Type

A/B | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Final | Karlgren[172] | Li[172] | Norman[173] | Baxter[172] | Zhengzhang[174] | Baxter–Sagart[175] | |

| I | 寒 Can | *Cân | *Can | *Cˤan | *Can | *Caːn | *Cˤan | A |

| II | 山 Cɛn | *Căn | *Crian | *Cren | *Cren | *Creːn | *Cˤren | |

| 刪 Cæn | *Can | *Cran | *Cran | *Cran | *Craːn | *Cˤran | ||

| III | 仙 Cjen | *Ci̯an | *Cjian | *Cen | *Crjan, *Crjen | *Cran, *Cren | *Cran, *Cren | B |

| 仙 Cjien | *Cjen | *Cen | *Cen | |||||

| 元 Cjon | *Ci̯ăn | *Cjan | *Can | *Cjan | *Can | *Can | ||

| IV | 先 Cen | *Cian | *Cian | *Cˤen | *Cen | *Ceːn | *Cˤen | A |

Rhymes

Most workers assume that words that rhymed in the Shijing had the same main vowel and the same final consonant, though they differ on the particular vowels reconstructed. The 31 traditional Old Chinese rhyme groups could thus be accounted for with four vowels, which Li Fang-Kuei reconstructed as *i, *u, *ə and *a. However some of the rhyme groups reconstructed with *ə or *a gave rise to more than one Middle Chinese rhyme group. To represent these distinctions, he also included three diphthongs *iə, *ia and *ua.[79]

In the early 1970s, Nicholas Bodman proposed a six-vowel system for an earlier stage of Chinese.[90] Applying Bodman's suggestion to Old Chinese, Zhengzhang Shangfang, Sergei Starostin and William Baxter argued that the 31 traditional rhyme groups should be split into more than 50 groups.[18][19][20] Baxter supported this thesis with a statistical analysis of the rhymes of the Shijing, though there were too few rhymes with codas *-p, *-m and *-kʷ to produce statistically significant results.[176]

For the Old Chinese rhyme groups with nasal codas in Middle Chinese (the yáng 陽 groups), which are assumed to reflect nasal codas in Old Chinese, six-vowel systems produce a more balanced distribution, with five or six rhymes for each coda, and at most four different finals for in each rhyme:[177]

- a final of division I or IV, arising from a type A syllable without an *-r- medial,

- a final of division II, arising from a type A syllable with an *-r- medial,

- a mixed division III or chongniu-3 final, arising from a type B syllable with an *-r- medial, and

- a pure division III or chongniu-4 final, arising from a type B syllable without an *-r- medial.

In syllables with acute initials, the two types of type B final are not distinguished, and the presence or absence of the former *-r- medial is reflected by the initial.

| Shijing rhyme group |

Middle Chinese finals | Old Chinese reconstructions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divs. I, IV | Div. II | Mixed, III-3 | Pure, III-4 | Li | Baxter | Zhengzhang[178] | |

| 侵 qīn[179] | 添 -em | 咸 -ɛm | 侵 -im | 侵 -jim | *-iəm | *-im | *-im |

| 覃 -om | *-əm | *-ɨm, *-um | *-ɯm | ||||

| 談 tán[180] | 添 -em | 鹽 -jem | 鹽 -jiem | *-iam | *-em | *-em | |

| 談 -am | 銜 -æm | 嚴 -jæm[i] | *-am | *-am | *-am, *-om | ||

| 覃 -om | 咸 -ɛm | *-am | *-om | *-um | |||

| 真 zhēn[182] | 先 -en | 山 -ɛn | 真 -in | 真 -jin | *-in | *-in | *-in |

| 文 wén/諄 zhūn[183] | 痕 -on, 先 -en[j] | 殷 -jɨn | *-iən | *-ɨn | *-ɯn | ||

| 魂 -won | 山 -wɛn | 諄 -win | 文 -jun | *-ən | *-un | *-un | |

| 元 yuán/寒 hán[184] | 先 -en | 山 -ɛn | 仙 -jen | 仙 -jien | *-ian | *-en | *-en |

| 寒 -an | 刪 -æn | 元 -jon | *-an | *-an | *-an | ||

| 桓 -wan | 刪 -wæn | 仙 -jwen | 元 -jwon[k] | *-uan | *-on | *-on | |

| 蒸 zhēng[186] | 登 -ong | 耕 -ɛng | 蒸 -ing | *-əng | *-ɨng | *-ɯŋ | |

| 耕 gēng[187] | 青 -eng | 庚 -jæng | 清 -j(i)eng | *-ing | *-eng | *-eŋ | |

| 陽 yáng[188] | 唐 -ang | 庚 -æng | 陽 -jang | *-ang | *-ang | *-aŋ | |

| 東 dōng[189] | 東 -uwng | 江 -æwng | 鍾 -jowng | *-ung | *-ong | *-oŋ | |

| 冬 dōng/中 zhōng[190] | 冬 -owng | 東 -juwng | *-əngw | *-ung | *-uŋ | ||

Finals with stop codas (traditionally classified as the entering tone) generally parallel those with nasal codas, with the addition of three groups with Middle Chinese reflexes in -k. Recent reconstructions assign these an Old Chinese coda *-wk corresponding to the labiovelar initial *kʷ-.[191]

| Shijing rhyme group |

Middle Chinese finals | Old Chinese reconstructions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divs. I, IV | Div. II | Mixed, III-3 | Pure, III-4 | Li | Baxter | Zhengzhang[178] | |

| 緝 qì[192] | 怗 -ep | 洽-ɛp | 緝-ip | 緝-jip | *-iəp | *-ip | *-ib |

| 合 -op | *-əp | *-ɨp, *-up | *-ɯb | ||||

| 葉 yè/盍 hé[193] | 怗 -ep | 葉 -jep | 葉 -jiep | *-iap | *-ep | *-eb | |

| 盍 -ap | 狎 -æp | 狎 -jæp[l] | *-ap | *-ap | *-ab, *-ob | ||

| 合 -op | 洽 -ɛp | *-ap | *-op | *-ub | |||

| 質 zhì[194] | 屑 -et | 黠 -ɛt | 質 -it | 質 -jit | *-it | *-it | *-id |

| 物 wù/術 shù[195] | 沒 -ot, 屑 -et[j] | 迄 -jɨt | *-iət | *-ɨt | *-ɯd | ||

| 沒 -wot | 黠 -wɛt | 術 -wit | 物 -jut | *-ət | *-ut | *-ud | |

| 月 yuè[196] | 屑 -et | 黠 -ɛt | 薛 -jet | 薛 -jiet | *-iat | *-et | *-ed |

| 曷 -at | 鎋 -æt | 屑 -jot | *-at | *-at | *-ad | ||

| 末 -wat | 黠 -wɛt | 薛 -jwet | 月 -jwot | *-uat | *-ot | *-od | |

| 職 zhí[197] | 德 -ok | 麥 -ɛk | 職 -ik | *-ək | *-ɨk | *-ɯg | |

| 錫 xī[198] | 錫 -ek | 陌 -jæk | 昔 -j(i)ek | *-ik | *-ek | *-eg | |

| 鐸 duó[199] | 鐸 -ak | 陌 -æk | 藥 -jak | *-ak | *-ak | *-ag | |

| 屋 wū[200] | 屋 -uwk | 覺 -æwk | 燭 -jowk | *-uk | *-ok | *-og | |

| 覺 jué/沃 wò[201] | 沃 -owk | 屋 -juwk | *-əkw | *-uk | *-ug | ||

| 錫 -ek | *-iəkw | *-iwk | *-iug, *-ɯug | ||||

| 藥 yào[202] | various | 藥 -jak | *-akw | *-awk | *-aug, *-oug | ||

| 錫 -ek | *-iakw | *-ewk | *-eug | ||||

Some words in the Shijing 質 zhì and 物 wù rhyme groups have Middle Chinese reflexes in the departing tone, but otherwise parallel to those with dental finals. Li followed Karlgren in reconstructing such words with an Old Chinese coda *-d.[203] The suffix *-h in Li's notation is intended to represent the Old Chinese precursor to the Middle Chinese departing tone, without specifying how it was realized.[82] The Shijing 祭 jì group has Middle Chinese reflexes in the departing tone only, including some finals that occur only in the departing tone (marked below with the suffix -H). As the reflexes of this group parallel the Shijing 月 yuè group, Li reconstructed these also as *-dh. Following a suggestion of André-Georges Haudricourt, most recent reconstructions derive the Middle Chinese departing tone from an Old Chinese suffix *-s. The coda *-ts is believed to have reduced to -j in Middle Chinese.[204]

| Shijing rhyme group |

Middle Chinese finals | Old Chinese reconstructions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divs. I, IV | Div. II | Mixed, III-3 | Pure, III-4 | Li | Baxter | Zhengzhang[178] | |

| 質 zhì (in part)[205] | 齊 -ej | 皆 -ɛj | 脂 -ij | 脂 -jij | *-idh | *-its | *-ids |

| 物 wù/術 shù (in part)[206] | 咍 -oj, 齊 -ej[j] | 微 -jɨj | *-iədh | *-ɨts | *-ɯds | ||

| 灰 -woj | 皆 -wɛj | 脂 -wij | 微 -jwɨj | *-ədh | *-uts | *-uds | |

| 祭 jì[196] | 齊 -ej | 皆 -ɛj | 祭 -jejH | 祭 -jiejH | *-iadh | *-ets | *-eds |

| 泰 -ajH | 夬 -æjH | 廢 -jojH | *-adh | *-ats | *-ads | ||

| 泰 -wajH | 皆 -wɛj | 祭 -jwejH | 廢 -jwojH | *-uadh | *-ots | *-ods | |

Finals with vocalic codas generally parallel those with dental or velar codas.[207]

| Shijing rhyme group |

Middle Chinese finals | Old Chinese reconstructions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divs. I, IV | Div. II | Mixed, III-3 | Pure, III-4 | Li | Baxter | Zhengzhang[178] | |

| 脂 zhī[208] | 齊 -ej | 皆 -ɛj | 脂 -ij | 脂 -jij | *-id | *-ij | *-il |

| 微 wēi[209] | 咍 -oj, 齊 -ej[j] | 微 -jɨj | *-iəd | *-ɨj | *-ɯl | ||

| 灰 -woj | 皆 -wɛj | 脂 -wij | 微 -jwɨj | *-əd, *-ər | *-uj | *-ul | |

| 歌 gē[210] | 歌 -a | 麻 -æ | 支 -je, 麻 -jæ[m] | *-ar, *-iar | *-aj | *-al, *-el | |

| 戈 -wa | 麻 -wæ | 支 -jwe | *-uar | *-oj | *-ol | ||

| 之 zhī[212] | 咍 -oj | 皆 -ɛj | 之 -i | *-əg | *-ɨ | *-ɨ | |

| 支 zhī/佳 jiā[213] | 齊 -ej | 佳 -ɛɨ | 支 -je | 支 -jie | *-ig | *-e | *-e |

| 魚 yú[214] | 模 -u | 麻 -æ | 魚 -jo, 麻 -jæ[m] | *-ag, *-iag | *-a | *-a | |

| 侯 hóu[215] | 侯 -uw | 虞 -ju[n] | *-ug | *-o | *-o | ||

| 幽 yōu[216] | 豪 -aw | 肴 -æw | 尤 -juw | *-əgw | *-u | *-u | |

| 蕭 -ew | 幽 -jiw | *-iəgw | *-iw | *-iu, *-ɯu | |||

| 宵 xiāo[217] | 豪 -aw | 宵 -jew | *-agw | *-aw | *-au, *-ou | ||

| 蕭 -ew | 宵 -jiew | *-iagw | *-ew | *-eu | |||

Because the Middle Chinese reflexes of the gē 歌 rhyme group do not have a -j coda, Li reconstructed it with an Old Chinese coda *-r.[218] However, many words in this group do have a -j coda in the colloquial layers of Min and Hakka varieties, in early loans into neighbouring languages, and in cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.[219]

Notes

- ^ 同聲必同部 Tóng shēng bì tóng bù.[15]

- ^ Middle Chinese forms given in Li's revision of Karlgren's notation.

- ^ Pulleyblank wrote the glottal stop as "·".[65]

- ^ Li wrote the glottal stop as "·".[76]

- ^ Baxter describes his reconstruction of the palatal initials as "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".[87]

- ^ Norman originally proposed pharyngealization only in type A syllables without retroflexion (the *-r- medial).[111]

- ^ Each of the main initials occurs both with and without pharyngealization.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i followed by a long vowel, causing palatalization.

- ^ This yields 凡 -jom after labial initials. The two finals are almost in complementary distribution, and also difficult to distinguish from -jem.[181]

- ^ a b c d -o- after velar initials, -wo- after labial initials, -e- after acute initials.

- ^ This final occurs only with velar or laryngeal initials, and could alternatively be reconstructed as *-an with a preceding labiovelar or labiolaryngeal initial.[185]

- ^ 乏 -jop after labial initials

- ^ a b The final -jæ occurs only after plain sibilant and palatal initials, with no known conditioning factor.[211]

- ^ 尤 -juw after some retroflex sibilant initials

References

Citations

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 12–13, 25.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 32–44.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 24–42.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Dong (2014), pp. 23–24.

- ^ GSR 1007a,p,k.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 13.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 346–347.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 5.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 42.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), p. 12.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 831.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 150–170.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 42–44.

- ^ a b c Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c Starostin (1989), pp. 343–429.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), pp. 180, 253–254, 813.

- ^ Norman (1973), pp. 227, 230, 233, 235.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 228–229.

- ^ Norman (1986), p. 381.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1992), p. 375–379.

- ^ Coblin (1983), p. 7.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 4–7.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 44.

- ^ Dong (2014), pp. 33–35.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1973).

- ^ Downer (1959).

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 49.

- ^ Handel (2012), pp. 63–71.

- ^ Sagart (1999), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Handel (2003), p. 547.

- ^ a b Handel (2003), p. 548.

- ^ Karlgren (1923), p. 18.

- ^ Karlgren (1923), p. 31.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), pp. 230–231.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), p. 230.

- ^ Karlgren (1957), p. 3.

- ^ a b Li (1974–1975), p. 244.

- ^ Karlgren (1957), p. 4.

- ^ GSR 272e,a.

- ^ GSR 937s,v.

- ^ Karlgren (1923), pp. 27–30.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 843.

- ^ Karlgren (1957), p. 2.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 23, 178, 262.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 180, 250.

- ^ Yakhontov (1970).

- ^ Yakhontov (1965), p. 30.

- ^ Yakhontov (1978–79), p. 39.

- ^ Yakhontov (1965), p. 27.

- ^ a b Yakhontov (1978–79), p. 37.

- ^ Yakhontov (1978–79), p. 38.

- ^ Yakhontov (1965), p. 26.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 92–93, 121, 135–137.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 95–96.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 110–114.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 114–119.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), p. 117.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1973), p. 117.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 137–141.

- ^ a b c Pulleyblank (1962a), p. 141.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Haudricourt (1954a).

- ^ Haudricourt (1954b), pp. 363–364.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962b), pp. 216–225.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 54–57.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1962b), pp. 225–227.

- ^ Mei (1970).

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 45.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), p. 235.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b Li (1974–1975), p. 237.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 46.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), pp. 237–240.

- ^ a b Li (1974–1975), pp. 243–247.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 331–333.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 48.

- ^ a b Li (1974–1975), pp. 248–250.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 196–202.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 206.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 202–203.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 177.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 203.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 178–180.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 178–179, 214.

- ^ a b Bodman (1980), p. 47.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 367–564.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), p. 180.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 181–183.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 323–324.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. vii.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2003).

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. 14.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. 18.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. 25.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 48–53.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 33–43.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 63–68.

- ^ Norman (1993), p. 705.

- ^ Sagart (1999).

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 3–4, 30–37.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 4–6.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 252–268.

- ^ Sagart (1999), pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 43, 68–76.

- ^ a b Norman (1994).

- ^ a b Sagart (2007).

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Sagart & Baxter (2016), p. 182.

- ^ Sagart (1999), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Sagart (1999), p. 13.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 53.

- ^ Sagart (1999), pp. 81, 88.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 54–56.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 83–99.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 102–105.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 177–178.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 99–102.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 176–177.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 174.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 123–127.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 131–134.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 170–172.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 105–108.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 116–119.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 178–179.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 188–189.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 171–173.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 108–111.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 99, 111–112.

- ^ Karlgren (1923), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Branner (2011), pp. 132–137.

- ^ GSR 25, 668, 740; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 134–135; Baxter (1992), pp. 188, 199.

- ^ GSR 503, 742, 947; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 135–137; Li (1974–1975), pp. 235–236; Baxter (1992), pp. 188–189.

- ^ GSR 45, 725, 961; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 107–109; Li (1974–1975), pp. 228–229, 232–233, 242; Baxter (1992), pp. 191–195, 229.

- ^ GSR 82, 465, 976; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 114–119; Li (1974–1975), pp. 231–232; Baxter (1992), pp. 196–199, 225–226.

- ^ GSR 23, 272, 597; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 121–122; Li (1974–1975), p. 237; Baxter (1992), pp. 199–202.

- ^ GSR 94, 354, 1076; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 119–121, 131–133; Li (1974–1975), p. 236; Baxter (1992), pp. 191–196, 222.

- ^ GSR 5, 798, 812; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 126–129; Li (1974–1975), p. 232; Baxter (1992), pp. 203–206.

- ^ GSR 74, 552, 609; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 86–88, 98–107, 110–114; Li (1974–1975), pp. 233, 235; Baxter (1992), pp. 199, 206–208, 210–214.

- ^ GSR 55, 200, 653; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 86–92; Li (1974–1975), p. 233; Baxter (1992), pp. 207, 209–210.

- ^ GSR 2, 873, 1164; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 92–95; Li (1974–1975), pp. 235–237; Baxter (1992), pp. 208–209.

- ^ GSR 302, 538, 992; Pulleyblank (1962a), pp. 95–98; Li (1974–1975), pp. 233–235; Baxter (1992), pp. 214–216.

- ^ GSR 97, 255, 995; Pulleyblank (1962a), p. 95–98; Li (1974–1975), pp. 233–235; Baxter (1992), pp. 217–218.

- ^ GSR 19; Pulleyblank (1962a), p. 92; Li (1974–1975), pp. 235–237; Baxter (1992), pp. 216–217.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 32.

- ^ Haudricourt (1954b), p. 359.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), pp. 233–234.

- ^ Branner (2006), p. 24.

- ^ Branner (2006), p. 25.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 63–81.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 258–267, 280–282.

- ^ Branner (2006), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 236–258.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 287–290.

- ^ Norman (1994), pp. 400–402.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1977–1978), pp. 183–185.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 95.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 288.

- ^ Norman (1994), p. 400.

- ^ Zhengzhang (1991), pp. 160–161.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 48–57.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1992), p. 379.

- ^ Handel (2003), p. 550.

- ^ a b c Baxter (1992), pp. 370–371, 373.

- ^ Norman (1994), pp. 403–405.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. 58.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 43, 274, 277.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 560–562.

- ^ Zhengzhang (2000), p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Zhengzhang (2000), pp. 40–43.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 548–555.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 537–543.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 539.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 422–425.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 425–434.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 370–389.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 375.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 476–478.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 497–500.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 489–491.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 505–507.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 524–525.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 301–302.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 555–560.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 543–548.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 434–437.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 437–446.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), pp. 389–413.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 472–476.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 494–497.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 484–488.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 503–505.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 518–524.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 532–536.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 325–336.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 308–319.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 436–437.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 438–446.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 292–298.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 446–452.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 452–456.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 413–422.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 414, 479–481.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 464–472.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 491–494.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 478–483.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 500–503.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 507–518.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 526–532.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), pp. 250–251, 265–266.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 294, 297.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Bodman, Nicholas C. (1980), "Proto-Chinese and Sino-Tibetan: data towards establishing the nature of the relationship", in van Coetsem, Frans; Waugh, Linda R. (eds.), Contributions to historical linguistics: issues and materials, Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 34–199, ISBN 978-90-04-06130-9.

- Branner, David Prager (2006), "What are rime tables and what do they mean?", in Branner, David Prager (ed.), The Chinese Rime Tables: Linguistic Philosophy and Historical-Comparative Phonology, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–34, ISBN 978-90-272-4785-8.

- ——— (2011), "Phonology in the Chinese Script and its Relationship to Early Chinese Literacy" (PDF), in Li, Feng; Branner, David Prager (eds.), Writing and Literacy in Early China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 85–137, ISBN 978-0-295-99337-9.

- Coblin, W. South (1983), A Handbook of Eastern Han Sound Glosses, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, ISBN 978-962-201-258-5.

- Dong, Hongyuan (2014), A History of the Chinese Language, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-74389-7.

- Downer, G. B. (1959), "Derivation by Tone-Change in Classical Chinese", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 22 (1/3): 258–290, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00068701, JSTOR 609429, S2CID 122377268.

- Handel, Zev J. (2003), "Appendix A: A Concise Introduction to Old Chinese Phonology", Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction, by Matisoff, James, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 543–576, ISBN 978-0-520-09843-5.

- ——— (2012), "Valence-changing prefixes and voicing alternation in Old Chinese and Proto-Sino-Tibetan: reconstructing *s- and *N- prefixes" (PDF), Language and Linguistics, 13 (1): 61–82.

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (1954a), "De l'origine des tons en vietnamien" [The origin of tones in Vietnamese], Journal Asiatique, 242: 69–82. (English translation by Marc Brunelle)

- ——— (1954b), "Comment reconstruire le chinois archaïque" [How to reconstruct Old Chinese], Word, 10 (2–3): 351–364, doi:10.1080/00437956.1954.11659532. (English translation by Guillaume Jacques)

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1923), Analytic dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese, Paris: Paul Geuthner, ISBN 978-0-486-21887-8.

- ——— (1957), Grammata Serica Recensa, Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, OCLC 1999753.

- Li, Fang-Kuei (1974–1975), "Studies on Archaic Chinese", Monumenta Serica, 31, translated by Mattos, Gilbert L.: 219–287, doi:10.1080/02549948.1974.11731100, JSTOR 40726172.

- Mei, Tsu-lin (1970), "Tones and prosody in Middle Chinese and the origin of the rising tone" (PDF), Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 30: 86–110, doi:10.2307/2718766, JSTOR 2718766.

- Norman, Jerry (1973), "Tonal development in Min", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (2): 222–238.

- ——— (1986), "The origin of Proto-Min softened stops", in McCoy, John; Light, Timothy (eds.), Contributions to Sino-Tibetan studies, Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 375–384, ISBN 978-90-04-07850-5.

- ——— (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ——— (1993), "A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology by William H. Baxter", Book Reviews, The Journal of Asian Studies, 52 (3): 704–705, doi:10.2307/2058873, JSTOR 2058873, S2CID 162916171.

- ——— (1994), "Pharyngealization in Early Chinese", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 114 (3): 397–408, doi:10.2307/605083, JSTOR 605083.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1962a), "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese" (PDF), Asia Major, 9: 58–144.

- ——— (1962b), "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese, part 2" (PDF), Asia Major, 9: 206–265.

- ——— (1973), "Some new hypotheses concerning word families in Chinese", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (1): 111–125.

- ——— (1977–1978), "The final consonants of Old Chinese", Monumenta Serica, 33: 180–206, doi:10.1080/02549948.1977.11745046, JSTOR 40726239.

- ——— (1992), "How do we reconstruct Old Chinese?", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 112 (3): 365–382, doi:10.2307/603076, JSTOR 603076.

- Sagart, Laurent (1999), The Roots of Old Chinese, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, ISBN 978-90-272-3690-6.

- ——— (2007), "Reconstructing Old Chinese uvulars in the Baxter-Sagart system" (PDF), 40th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics.

- Sagart, Laurent; Baxter, William H. (2016), "A Hypothesis on the Origin of Old Chinese Pharyngealization (上古漢>語咽化聲母來源的一個假設)", Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics, 9 (2): 179–189, doi:10.1163/2405478X-00902002.

- Schuessler, Axel (1987), A Dictionary of Early Zhou Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1111-2.

- ——— (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Starostin, Sergei A. (1989), Rekonstrukcija drevnekitajskoj fonologičeskoj sistemy [Reconstruction of the Phonological System of Old Chinese] (PDF) (in Russian), Moscow: Nauka, ISBN 978-5-02-016986-9.

- Yakhontov, S. E. (1965), Drevnekitajskij jazyk [Old Chinese] (PDF) (in Russian), Moscow: Nauka.

- ——— (1970), "The phonology of Chinese in the first millennium BC (rounded vowels)", Unicorn, 6, translated by Norman, Jerry: 52–75: translation of Yakhontov, S. E. (1960), "Fonetika kitayskogo yazyka I tysyacheletiya do n.e. (labializovannyye glasnyye)", Problemy Vostokovedeniya, 6: 102–115.

- ——— (1978–79), "Old Chinese Phonology" (PDF), Early China, 5, translated by Jerry Norman: 37–40, doi:10.1017/S0362502800005873, S2CID 162162850, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-31, retrieved 2014-03-04: translation of Chapter 2 (Phonetics) of Yakhontov (1965).

- Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1991), "Decipherment of Yue-Ren-Ge (Song of the Yue boatman)", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 20 (2): 159–168, doi:10.3406/clao.1991.1345.

- ——— (2000), The Phonological system of Old Chinese, translated by Sagart, Laurent, Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, ISBN 978-2-910216-04-7.

- ——— (2003), Shànggǔ yīnxì 上古音系 [Old Chinese Phonology], Shanghai Educational Publishing House, ISBN 978-7-5320-9244-4.

Further reading

- Dong, Tonghe (1997) [1948], Shànggǔ yīnyùn biǎogǎo 上古音韻表稿 (in Chinese), ISBN 978-5-666-71063-0. Reprint of Dong, Tonghe (1948), "Shànggǔ yīnyùn biǎogǎo" 上古音韻表稿 [Tentative Archaic Chinese Phonological Tables], Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology (in Chinese), 18: 1–249.

Book reviews

- Baxter (1992):

- Behr, Wolfgang (1999), Odds on the Odes, archived from the original on 19 May 2011.

- Boltz, William (1993), "Notes on the Reconstruction of Old Chinese" (PDF), Oriens Extremus, 36 (2): 186–207, JSTOR 24047376.

- Coblin, W. South (1995), "William H. Baxter: A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology", Monumenta Serica, 43: 509–519, doi:10.1080/02549948.1995.11731284, JSTOR 40727078.

- Norman, Jerry (1993), "A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology by William H. Baxter", Book Reviews, The Journal of Asian Studies, 52 (3): 704–705, doi:10.2307/2058873, JSTOR 2058873, S2CID 162916171.

- Peyraube, Alain (1996), "William H. Baxter, A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology", T'oung Pao (in French), 82 (1/3): 153–158, doi:10.1163/1568532962631094, JSTOR 4528688.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1993), "Old Chinese phonology: a review article", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 21 (2): 337–380, JSTOR 23753918.

- Sagart, Laurent (1993), "New Views on Old Chinese Phonology", Diachronica, 10 (2): 237–260, doi:10.1075/dia.10.2.06sag.

- Sagart (1999):

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2002), "The Roots of Old Chinese. Laurent Sagart", Anthropological Linguistics, 44 (2): 207–215, JSTOR 30028844.

- Mair, Victor (2004), "Laurent Sagart. The Roots of Old Chinese" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 145: 17–20.

- Miyake, Marc (2001), "Laurent Sagart : The Roots of Old Chinese", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 30 (2): 257–268, doi:10.1163/19606028-90000092.

- Rubio, Gonzalo (2001), "The Roots of Old Chinese, by Laurent Sagart", Language, 77 (4): 870, doi:10.1353/lan.2001.0238, S2CID 144190569.

- Schuessler, Axel (2000), "Book Review: The Roots of Old Chinese" (PDF), Language and Linguistics, 1 (2): 257–267.

- Ting, Pang-Hsin (2002), "Morphology in Archaic Chinese", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 30 (1): 194–210, JSTOR 23754869.

- Zhengzhang (2000):

- Boltz, William (2002), "Zhengzhang Shangfang : The Phonological system of Old Chinese", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 31 (1): 105–116, doi:10.1163/19606028-90000100.

- Schuessler (2007):

- Starostin, Georgiy (2009), "Axel Schuessler : ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese" (PDF), Journal of Language Relationship, 1: 155–162.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014):

- Goldstein, D.M. (2015), "William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart: Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 78 (2): 413–414, doi:10.1017/S0041977X15000361, S2CID 164868923.

- Harbsmeier, Christoph (2016), "Irrefutable Conjectures. A Review of William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart, Old Chinese. A New Reconstruction" (PDF), Monumenta Serica, 64 (2): 445–504, doi:10.1080/02549948.2016.1259882, S2CID 171165858. (Presentation on YouTube)

- Hill, Nathan W. (2017), "Old Chinese. A New Reconstruction", Archiv Orientální, 85 (1): 135–140, doi:10.47979/aror.j.85.1.135-140, S2CID 255254929.

- Ho, Dah-an (2016), "Such errors could have been avoided – review of Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 44 (1): 175–230, doi:10.1353/jcl.2016.0004, S2CID 170231803.

- Jacques, Guillaume (2017), "On the status of Buyang presyllables: A Response to Professor Ho Dah-An", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 45 (2): 451–457, doi:10.1353/jcl.2017.0019, S2CID 172031292.

- List, Johann-Mattis; Pathmanathan, Jananan Sylvestre; Hill, Nathan W.; Bapteste, Eric; Lopez, Philippe (2017), "Vowel purity and rhyme evidence in Old Chinese reconstruction", Lingua Sinica, 3 (5): 139–160, doi:10.1186/s40655-017-0021-8.

- Ma, Kun (2017), "历史比较下的上古汉语构拟——白一平、沙加尔(2014)体系述评" [Historical reconstruction of Old Chinese – a review of the system of Baxter and Sagart (2014)] (PDF), Zhōngguó yǔwén (in Chinese) (4): 496–509.

- Schuessler, Axel (2015), "New Old Chinese", Diachronica, 32 (4): 571–598, doi:10.1075/dia.32.4.04sch.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2018), "Old Chinese reconstruction: A response to Schuessler", Diachronica, 34 (4): 559–576, doi:10.1075/dia.17003.sag.

- Starostin, George (2015), "William H. Baxter, Laurent Sagart. Old Chinese. A New Reconstruction" (PDF), Journal of Language Relationship, 13 (4): 383–389, doi:10.31826/jlr-2016-133-412, S2CID 212688788.

External links

- StarLing database, by Georgiy Starostin.

- Baxter-Sagart reconstruction of Old Chinese

- "Duōwéi shìyě xià de shànggǔ yīn yánjiū" 多维视野下的上古音研究 [Views on research on Old Chinese phonology], Wénhuì Xuérén (in Chinese): 2–6, 11 August 2017.