Appalachian Spring

| Appalachian Spring | |

|---|---|

Graham, c. 1940 | |

| Choreographer | Martha Graham |

| Music | Aaron Copland |

| Premiere | October 30, 1944 Coolidge Auditorium |

| Original ballet company | Martha Graham Dance Company |

| Characters |

|

| Design |

|

| Setting | 19th-century Pennsylvania |

| Created for |

|

| Genre | Modern dance |

Appalachian Spring is a ballet and orchestral work by the American composer Aaron Copland and the choreographer Martha Graham. It was composed for Graham upon a commission by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge; the original choreography and costumes were by Graham with sets by Isamu Noguchi. The work was very successful after its 1944 premiere, winning Copland the Pulitzer Prize for Music the following year. It has remained among Copland's most well-known works, particularly the orchestral suite composed in 1945.

The ballet takes place in a small settlement in 19th century Pennsylvania. There are four main characters: the Bride, a brave woman; the Husbandman, who is to marry the Bride; the Pioneer Woman, the mother of the Bride; and the Revivalist, an evangelist with four Followers. The ballet follows the Bride and the Husbandman as they get married and celebrate with the community. Themes of war are present throughout the story; it is suggested that the Husbandman leaves for war, causing worry and anxiety among the community. Shaker themes also influenced the ballet, notably in the music, where Copland incorporated a theme and variations on the common Shaker tune "Simple Gifts".

During the Great Depression, Copland's political ideals began shifting further left; as a result, he had the idea to create ordinary music for the public, music that was easy and accessible enough for the general citizen to understand. He used this idea in Americana populist ballets like Billy the Kid and Rodeo, and works like Lincoln Portrait and Fanfare for the Common Man received widespread acclaim for their American themes. In 1942, Coolidge commissioned Copland to compose a ballet for Graham. The initial scenario that Graham sent to Copland was revised many times by both Copland and Graham, and the final result drew from a number of the revisions. The ballet features eight episodes, three of which were cut in the later orchestral suite.

History

Background

Aaron Copland was born in 1900 to Jewish immigrants to the United States.[1][2] The Copland family lived above their Brooklyn department store, which his parents spent much of their time managing; as a result, Copland was entrusted to the care of his older siblings. He was particularly close to his sister Laurine, who exposed him to ragtime and opera, and taught him to play the piano.[1][2][3] At age seven, he created short tunes at the piano, and at age twelve, he began notating short pieces.[1][4] In 1917, the young musician began taking music theory and composition lessons with Rubin Goldmark,[5] and in 1921, he began attending the American Conservatory just outside of Paris,[6][7] where he was taught composition by Nadia Boulanger.[7][8] Boulanger introduced Copland to a wide range of music, from the baroque and classical styles of music to the modern music of Ravel and Stravinsky (the latter of whom was one of Copland's greatest influences).[7][9][10] In 1925, the composer received his big break with the premiere of his Symphony for Organ and Orchestra by the New York Symphony Orchestra and subsequent performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[1][11][12]

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Copland spent much of his time promoting American composers and music.[13] The composer joined the New York-based League of Composers, for whom he wrote journal, magazine, and newspaper articles on music.[1] Various other engagements took up the rest of his time, including lectures, teaching, and small commissions; these kept him financially stable during the Great Depression and World War II.[14] Copland's compositions during this time turned jazzy and dissonant,[15][16] a style that interested few.[13] During the depression, his left-wing political stances strengthened, motivated by addressing the concerns of ordinary people.[1][13][17] This brought forth the idea of music that was simple and accessible enough to be liked by the general public,[13][18] an idea pioneered in his opera for children The Second Hurricane (1937) and his greatly successful ballet El Salón México (1936).[13][19][20] This "ordinary music" idea is certainly present in Appalachian Spring; Copland remarked in a 1980 interview that the music was "plain, singing, comparatively uncomplicated and slightly folksy. Direct and approachable."[21] The composer solidified his populist and Americana style with ballets like Billy the Kid (1938) and Rodeo (1942),[22][23] both of which used cowboy songs and fit with the popular stereotypes about the wild west.[23][24] In addition, Lincoln Portrait (1942) and Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) received widespread acclaim for its American themes, distinguishing Copland as one of the most versatile composers of the 20th century.[25]

Martha Graham was a modern dancer and choreographer best known for creating the "Graham technique" of dance.[26][27] The Martha Graham Dance Company originally consisted of only women due to Graham's feminism; this played a key role in productions like American Document (1938), which mixed important moments in American history with various bizarre scenes.[28] In the 1930s, she began commissioning scores from various composers; the scenarios often involved American history and culture.[26]

Commission and composition

In 1941, Graham proposed to Copland a dark ballet about Medea, but, despite being a great admirer of Graham, he declined.[29] The following year, Erick Hawkins, the chief male dancer in Graham's dance company, convinced the music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge to commission a ballet from Copland for Graham's company; Copland happily accepted the offer.[30] Graham first proposed a scenario titled "Daughter of Colchis", which was inspired by the story of Medea but set in 19th century New England. Copland found it "too severe", and the idea was given to another Coolidge commissionee, Carlos Chávez.[29] In May 1943, Graham sent Copland a scenario titled "House of Victory", about a newlywed couple in a small 19th century Pennsylvania settlement. Copland revised the scenario before composing on the music, though his occupation with The North Star caused the beginning of his work to be delayed.[29][31]

Per Coolidge's commission, the orchestra was to be no bigger than twelve musicians.[29] Copland originally planned to orchestrate it for double string quartet and piano, but later decided to add a double bass, flute, clarinet, and bassoon, a scoring similar to Chávez's work.[32] Copland wrote much of the composition on the West Coast, far from Graham's east-coast-based work.[33][34] Since he could not meet with Graham, he relied greatly on the various scenarios sent to him. In total, Copland was sent three scripts: the original "House of Victory", and two revisions titled "Name".[32][35] In composing the music, he drew from all three scripts to devise his own scenario, which Graham planned around as she received various drafts of the score.[36] Copland used the working title "Ballet for Martha" during the composition process.[37]

The original scenario, "House of Victory", used characters based on common American archetypes and was set during the Civil War, but also drew from Greek mythology and French poetry.[a][39][40] Four main characters were present: the Mother, who represents the preindustrial American; the Daughter, a brave pioneer; the Citizen, a smart civil rights advocate who marries the Daughter; and the Fugitive, who embodies the slave in the Civil War.[39][41][42] Graham based some of the ballet on her own experiences. She grew up in small-town Pennsylvania, and she later wrote that the Mother was based on her own grandmother.[41][43] Other characters include the Younger Sister, Two Children, and Neighbors.[44][41] In the later revisions, a new character was added: an Indian girl to represent the land, associated with the story of Pocahontas. The Indian girl was meant to act as a theatrical device, interacting with everyone in the ballet yet never being acknowledged, but the idea was scrapped in Copland's final composition.[31][41][45] Additionally, Graham planned for the Mother to speak excerpts from the Book of Genesis throughout, "not in a religious sense so much as in a poetic sense";[46] this too was cut by the premiere.[47]

The final scenario featured eight episodes:[b][46]

- Prologue: Graham did not want "Prologue" to be long; she wanted it to have "a sense of simple celebration". As the lights went up, the Mother observed her land.[46]

- Eden Valley: The Daughter and the Citizen dance together in a "duet of courtship".[46]

- Wedding Day: Graham divided "Wedding Day" into two parts. The first opens with a dance between the Younger Sister and the Two Children. The Citizen exhibits his strength before carrying the Daughter into the couple's new home. In the second part, the Daughter and the Citizen dance a love scene in the home, while those outside celebrate in an "old fashion charivari".[46]

- Interlude: The "Interlude" depicts daily life in the town during spring planting.[46]

- Fear in the Night: This episode was meant to be the central conflict of the ballet. The Fugitive enters with an "awkward" and "tragic" solo, bringing forth the fear and suffering of the Civil War.[46][48]

- Day of Wrath: This episode was intended to represent the tragedies of war, accompanied by music reminiscent of the Civil War. The Citizen dances a violent solo "reminiscent of Harper's Ferry and John Brown" while the Two Children play a war game.[49][50]

- Moment of Crisis: The women of the town gather and suggest "a barely suppressed hysteria".[51]

- The Lord's Day: The final scene was intended to depict "Sabbath in a small town". The Daughter and the Citizen perform a love duet outside the home, and the rest of the community attends a revival meeting.[51][52]

The "House of Victory" script contained an extra episode after the "Interlude" presenting scenes from Uncle Tom's Cabin, strengthening the ballet's connection to the Civil War; but, upon Copland's persuasion, Graham cut the episode from the revisions.[44][51] In addition, the original script used a different final scene, where the Daughter and the Citizen reunite in the home. The second script ended with "the town settling down for the night" and the Daughter standing at the fence just before the curtain falls. The third script put forth "The Lord's Day" as it would stand in the final scenario.[51]

Copland completed the condensed score in June 1944, and the orchestration was finished in August.[32] The premiere was originally set to take place at the Library of Congress on October 30, 1943, which was Coolidge's birthday. By May 1943, Copland had not begun composing the ballet, and given the further problems introduced by World War II, the premiere was postponed to the spring of 1944.[29] Despite a new December deadline for the music, a completed score was still not in view, and the premiere was pushed to the fall.[32]

Production

Shortly before the premiere, Graham decided upon the title "Appalachian Spring".[c] It was taken from the cycle of poems The Bridge[d] by Hart Crane, an American poet also seeking to create unique American art;[52][54] one of the poems, titled Powhatan's Daughter, contained the line "O Appalachian Spring!"[52][55] Crane's work was a great inspiration to Graham while she wrote the various scripts.[54][56] To construct the set, Graham hired Isamu Noguchi, a Japanese-American sculptor and common collaborator of the company. While planning, she took Noguchi to the Museum of Modern Art and showed him Alberto Giacometti's sculpture The Palace at 4 a.m.[e] as a reference for what she wanted:[57] something depicting the inside and outside of a house without actually dividing it, a sort of blurred mix. Noguchi's use of an outline of a house served as a metaphor for the general idea of the work being about "the bone structure of a people's living".[58][59] The set featured the outline of a house, part of a porch with a ledge, a rocking chair, a small fence, and a tree stump (serving as the Revivalist's pulpit).[40][60] Edythe Gilfond created the costumes and Jean Rosenthal designed the lighting.[61][62][63]

Many changes were made to the scenario after the score was finished. The Younger Sister, the Two Children, and the Neighbors were all cut, and the rest of the cast was renamed: the Daughter, now the Bride; the Citizen, now the Husbandman; the Mother, now the Pioneer Woman; and the Fugitive, now the Revivalist.[f][31][64] Four Followers of the Revivalist were added to the cast for a total of nine dancers.[64] The choreography often deviated from both the final scenario and Copland's annotations in the score; for example, the closing love duet between the Bride and the Husbandman became a dance between the Revivalist and his four Followers.[65] Regardless, Copland was not irritated by this, later commenting, "That kind of decision is the choreographer's, and it doesn’t bother me a bit, especially when it works."[66] The cast at the premiere starred Graham as the Bride, Hawkins as the Husbandman, May O'Donnell as the Pioneer Woman, and Merce Cunningham as the Revivalist.[67] Yuriko, Pearl Lang, Nina Fonaroff, and Marjorie Mazia danced the Revivalist's followers.[68][69]

Graham's performance was young and lively, something that was praised by critics.[70][71] On the contrary, Hawkins was more stiff, exhibiting a masculinity and suppleness that stuck in the role with future performers. Cunningham, who choreographed his own solo during Fear of the Night, was instructed to displayer great anger; Graham later described to role to a new dancer as being "ninety-nine percent sex and one percent religion: a real popular spellbinder, a magnetic man who had power over women."[70] Graham's vision for the four Followers was spontaneity; they would remain perfectly still until their time came, and when they did dance, it would be with energy and focus. Agnes de Mille, fellow choreographer and close friend of Graham's, pointed out that many subsequent productions featured cute and perky Followers, but that this was not Graham's original intention.[72] Much of the contrast between female and male characters was intentional. While the female characters remained bouncy and light, the male characters were stiff and took up much space.[73] The choreography (and, to an extent, the plot) are abstract; despite being about a wedding in small community, there is never a wedding literally depicted on stage, rather expressions of love between the couple.[74]

The choreography was described by the press as simple and precise.[75][76][77] Despite being set during in such a scenario, the choreography does not explicitly depict a wedding; rather, the dance expresses the emotions of individual characters.[61] This non-literal plot allowed for free emotional interpretation by the audience.[78] The Bride's movements featured quick patterns that stayed within an imaginary box around her. This contrasted with the Revivalist's strict posture and the flowing movements of the Pioneer Woman.[79] One reviewer pointed out the solitude of the characters and its manifestation in their movements, writing, "The separateness of still figures... which their poses emphasize, suggests that people who live in these hills are accustomed to spending much of their time alone."[80] Another reviewer described the choreography as having "very little of what is ordinarily termed dancing... [with] much acrobatic posturing..."[76]

Premiere and reception

Appalachian Spring premiered on October 30, 1944, at the Coolidge Auditorium, conducted by Louis Horst, the music director of the company.[g][82][83] The premiere was the closing concert of a four-day chamber music festival honoring Coolidge's 80th birthday.[84][85] Copland had not attended any of the rehearsals at Graham's request, first seeing the full performance a day before the premiere.[86][36] The ballet was well-received by critics and the public.[81][67][87] The New York Times critic John Martin wrote of the music, "Aaron Copland has written a score of fresh and singing beauty. It is, on its surface, a piece of early Americana, but in reality it is a celebration of the human spirit."[88] The Dance Observer critic Robert Sabin wrote of the story, "Appalachian Spring works outward into the basic experiences of people living together, love, religious belief, marriage, children, work and human society."[81] The dance was also praised; Martin continued, "There is throughout the work a very moving sense of the future, of the fine and simple idealism which animates the highest human motives."[88] The dance critic Walter Terry praised Graham in particular, writing in 1953, "Miss Graham brought to the role a wonderful radiance which dominated the entire ballet."[89] The group of dancers was commended for being well-trained and enthusiastic.[75] Copland's idea for ordinary music continued to be popular; one reviewer commented that it was "comprehensible even to the bored businessman".[44] Copland himself took a modest opinion of the premiere; a week later, he wrote in a letter, "People seemed to like it so I guess it was all right."[90]

The great demand for tickets caused a repeat of the October 30 program to occur the following evening.[91] Shortly after the premiere, the Graham Company took Appalachian Spring on tour across the United States with the same cast. The debut show of the tour took place in Washington, D.C., on January 23.[67][92] The New York premiere of the ballet occurred days after Victory in Europe Day; the ballet's American populist themes, combined with winning the Pulitzer Prize for Music in the same week, caused this show to be even more successful.[67][93][94] After every performance sold out, the New York run was extended by one night.[95]

Later performances

Appalachian Spring remains an essential production in the Martha Graham Dance Company repertoire.[61][96] Due to the high cost of licensing the ballet, it was not performed by another company until 1998, when the Colorado Ballet staged it under the artistic director Martin Fredmann.[97] In 2013, the Baltimore School for the Arts put on a production for the "Appalachian Spring Festival" in association with the Graham Company, which featured a complete performance of the ballet and various art exhibits. It marked the first time a non-professional company was granted permission from the Martha Graham Center to perform the ballet.[98] Appalachian Spring has been performed by numerous dance companies since, including the Onium Ballet Project in Hawaii,[99] the Nashville Ballet in Tennessee,[100] Dance Kaleidoscope in Indiana,[101] and the Sarasota Ballet in Florida.[102]

Many consider Appalachian Spring to be one of Copland's best and most famous works;[86][103] it holds equal notability in the Graham company's repertoire.[104][105] The critic Terry Teachout wrote, "It is probably the greatest piece of classical music composed by an American. Certainly the greatest dance score composed by an American, completely comparable in quality to the great ballets of Tchaikovsky or Stravinsky. All that is best about mid-century American music is in this piece."[86] In addition, the ballet was essential to the development of modern American ballet;[106] it and Copland's other Americana works represented the leftist national ideals important to the postwar era,[107] but used traditional themes, steering away from the outwardly political works of many New York artists at the time.[108] Lynn Garafola compared Copland and Graham's collaborations to that of Stravinsky and Diaghilev; whereas Stravinsky composed purely Russian scores for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Copland composed American music for Graham's company, helping define American dance.[109]

Themes

Themes of war are present throughout the conflict of Appalachian Spring.[110][111] The central conflict begins in the "Fear in the Night" episode, where the Revivalist delivers a haunting sermon. Howard Pollack argued that this scene represented the spirit of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, something that could cause the Husbandman to be drafted in the Civil War. Furthermore, the subsequent "Day of Wrath" episode can be seen as the Husbandman leaving for war, clarified by the closing waves of goodbye. "Moment of Crisis" is an expression of anxiety and concern for the Husbandman, and "The Lord's Day" is a prayer for peace and safety. When the Husbandman rejoins the Bride at the end, Pollack suggests this is actually in her imagination, further supported by her final gesture of reaching out to the horizon.[110] Mark Franko says that the Civil War themes are possibly a reference to the ongoing racial inequality in the United States and the Civil Rights movement.[38]

The opening of the music uses delicately placed dissonances to create a dreamy landscape. In the scripts Copland worked from, this scene was to feature the Pioneer Woman sitting "terrifyingly still" and looking over her land. Elizabeth Crist speculates that the entire ballet is the Pioneer Woman's memory; Crist suggests that the dissonances in the music depict the Pioneer Woman reflecting on the hardships she faced, and that the following episodes are entirely her own experiences.[112] Crist continues that when the opening themes are recalled at the end of the ballet, the Bride disconnects from the Pioneer Woman's memory, becoming her own individual memory; the Bride sits where the Pioneer Woman sat at the beginning, the context having shifted to a new time. Crist describes this as an embodiment of the link between wars among generations: as World War II was linked to the Civil War, the Bride brings together the life on the homefront in the 19th and 20th centuries.[103] Graham's explanation for this was the fluidity of time, where younger generations feel the ramifications of things the older generations experienced.[113]

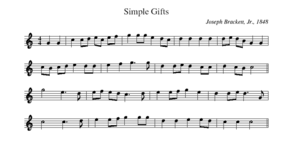

Shaker themes are also heavily present in Appalachian Spring.[114][115] The idea of using Shaker themes is found in the original "House of Victory" script, where the Pioneer Woman is said to sit in a "Shaker rocking chair".[114][116] Copland's interest in Shakers was not new, as they became a common subject of American art during the Great Depression.[114][115] After Copland included the Shaker tune "Simple Gifts" into the "Interlude", Graham added "The Lord's Prayer" as a possible "Shaker meeting".[h][118] Copland had decided to use "Simple Gifts" early on; by extracting a basic melodic motif from the tune, he created variations on it throughout the composition, first referring to it in the opening measures.[119][120] The lyrics of "Simple Gifts" had a connection to the ballet's themes of war and peace: "'Tis the gift to be simple, 'tis the gift to be free".[121]

Instrumentation

The original ballet and subsequent suite for chamber orchestra are scored for:[122][123][124]

|

The suite for orchestra and ballet arrangement for orchestra are scored for:[125][126]

|

Music and plot

Prologue

The ballet opens with a soft, quiet melody in the clarinet. Throughout the prologue, different instruments repeat notes to build rising chords, some becoming carefully dissonant.[127] The Revivalist enters first, in darkness, followed by the Pioneer Woman, who takes a seat in her rocking chair. Then, the Husbandman and Bride enter; as the Husbandman paused to observe the home, daylight illuminated the stage.[128][129] The four Followers join the Revivalist, who has observed the land with the Pioneer Woman.[63] The two-minute opening set up the themes present throughout the ballet, and Copland employed the upwards building of chords to depict a "nonmilitant fanfare", as Graham described in the early scripts.[63][130]

Eden Valley

![\relative c''' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = "piano" \clef treble \key c \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Allegro" 4 = 160 a8_\markup { \dynamic f \italic \small { vigoroso } }-> a, a'4 a8 cis a4->~ | a1\fermata | e'8->[ a,] e[ cis] a[ e] a,4->~ | a1\fermata }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/3/k3spgb8kkbtj6j6i9200h0hvqptl5a9/k3spgb8k.png)

Suddenly, an energetic melody comes forth as the Daughter bounds from inside the home. The swing-like melodies of "Eden Valley" express the Bride's joy. Halfway, the music calms down, reflecting the sound of a hymn. As the Husbandman enters, jagged rhythms shows his awkward movement; it's twice interrupted by a caring melody (the "love theme") in the clarinet, showing the Husbandman's shy feelings. As the two back out of the home, the duet continues, this time with louder and more forceful strings as the couple fall to their knees in prayer. The two receive the blessings of the Pioneer Woman and the Revivalist. This section is reminiscent of the Cowgirl's music from Rodeo, or the soft parts of Lincoln Portrait for the love theme; near the end, the clarinet brings back the love theme, and the flute answers, a depiction of the Bride and the Husbandman.[130][112] Throughout the episode, the Followers participate in various group solos; the group often features a "spiraling" motion, moving into a kneeling position. Eden Valley closes with the Followers returning to the bench, each taking a seat one-by-one. Illustrating the choreographies close connection to the music, the moment each Follower sits is cued by a short phrase by a woodwind.[131]

Wedding Day

![\relative c''' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = "clarinet" \clef treble \transposition bes \key des \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Fast" 4 = 132 r8 ges_\markup { \dynamic mp \italic \small { playfully } }-. f-.[ des-.] ees16( f ges8-.) aes4-- }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/j/d/jdenjocc3eupi75znmnfho6pwpablfh/jdenjocc.png)

A playful, childlike melody springs from the clarinet, opening the first part of Wedding Day and signifying the start of festivities. Graham wanted the first part to have "a little sense of a County Fair, a little of a revival meeting, a party, a picnic"; Copland achieves this by relating the music to American folk themes, particularly in the music's relation to fiddling.[130] The music becomes heavier for and the jagged rhythms return for the Husbandman's Davy Crockett-esque solo, and the love theme returns in the calmer music as the Husbandman carries the Bride into the home.[132]

The second part of Wedding Day depicted the "old fashion charivari" mentioned in the scripts. The joyous and bouncy music uses scales and rhythmic jolts to conjure the image of party and celebration. As the music calms down, the newlywed couple in the home rests. The theme from the Prologue returns, and the light focuses on the Pioneer Woman's face, then fades into darkness.[121]

Interlude

|

| Music |

|---|

|

| Works inspired by Simple Gifts |

|

| Works inspired by Shakers |

|

Copland used the Shaker song "Simple Gifts" throughout much of Appalachian Spring, first playing it in its entirety at the start of the Interlude.[120][121] Throughout the Interlude, he introduces four variations on "Simple Gifts", some fitting the atmosphere of the action on stage (like one variation reminiscent of the clip-clop of a horses' hooves). Most of the variations left the melody essentially the same, changing other elements of the music, like the harmony or what instruments played. This technique was meant to depict the lives of various townspeople doing their daily rounds, and the Husbandman and the Bride danced joyfully during it.[121][133] The two are greatly connected throughout the duet, signified by eye contact, ease of physical touch, and openness of the body.[134] Partway through, the Revivalist and his Followers join in. The Revivalist solos in close alignment with the bassoon, the Followers following along.[135] During the fourth variation, the Revivalist dominantly watches their high-spirited duet, and follows the couple as they walk into the home.[112][134]

Fear in the Night, Day of Wrath, Moment of Crisis

The Revivalist takes off his hat and approaches the bowing Husbandman and Bride.[112] The Revivalist's four Followers surround him as he warns the couple of their love.[133] His agonized, frenzied dance was informed by the experiences of Peter Sparling, a dancer in the company who'd dance the role in later productions.[136] The Revivalist's solo uses violent shaking to relate the dance to traditional Shaker festivities; the shaking travels throughout the body, like a spirit trying to escape from the body.[137] The demonstration scares the Bride and sends her in a turmoil, but she quickly rejoins the Husbandman and accepts the risks of her love.[133] Graham used the motion of one part of the body to contradict another. For example, the Revivalist's open hand during his Fear of the Night solo is contradicted by him suddenly pulling it back.[138]

The music of Fear of the Night jolts and twitches, similar to the "Gun Battle" in Billy the Kid.[139] In "Day of Wrath", the Pioneer Woman enters with deep anger, and after prayer, she enters the home. The Husbandman leaves the home and performs a leaping solo, where the music uses a distorted version of the love theme and harsh, dissonant chords to evoke anguish as he waves goodbye and exits. The cheery Wedding Day music returns, accompanied by bugle calls; this scene was originally meant to include the Two Children, but they were cut in the final scenario.[140][141]

The Bride opens "Moment of Crisis" by frantically running across the stage, and the other women join in an anxious frenzy. The music becomes rushing and agitated into perpetual motion; consistent sixteenth-note patterns jump around the orchestra, with no sense of musical direction. The music begins to calm, and the love theme returns as the Husbandman briefly comes back to dance with the Bride. Another variation of "Simple Gifts" underlines the Husbandman's slow drift away, and a grand, final restatement of the song signals the end of the fear as the Pioneer Woman dances with the Followers.[142][141][143]

The Lord's Day

A gentle hymn-like melody is heard in the strings as the community gathers for prayer.[141][144] Graham wrote that this episode "could have the feeling of a Shaker meeting where the movement is strange and ordered and possessed or it could have the feeling of a negro church with the lyric ecstasy of the spiritual about it".[51] The Bride dances her final solo and finishes by putting her hand to her lips and then reaching out to the sky. The Husbandman returns and holds her briefly, but the Revivalist comes and touches his shoulder.[144] As the music from the prologue returns, the Bride sits in the rocking chair that the Pioneer Woman sat in and she looks over the empty stage. The Husbandman rests his hand on her shoulder and the Bride reaches out at the clarinet's last note. The music slowly fades to silence and the curtain falls.[103][104]

Suites

In May 1945, Copland arranged the ballet into a suite for a symphony orchestra, and many conductors programmed the work in the following seasons.[145] The suite for orchestra premiered October of that year by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Artur Rodzinski, and was well-received.[125][146] Other American orchestras expressed interest in the suite, with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Kansas City Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Cleveland Orchestra scheduling it that season.[147] Its great success made the (then on-tour) ballet even more popular, establishing Copland and Graham as highly regarded artists.[148] The Vienna premiere of the orchestral suite took place in November and the Australian premiere soon after.[149][150] In January 1946, the Martha Graham Dance Company presented a new run of shows in New York, including Appalachian Spring on the program.[151] By May 1946, the orchestral suite had received performances across the world.[152]

The orchestral suite is divided into eight sections, named by their tempo markings instead of episode titles in the ballet.[50] In the suites, Copland omitted the conflict of the story (Fear in the Night, Day of Wrath, and Moment of Crisis), making these episodes unfamiliar to the public and seldom recorded.[50][121] The popularity of the orchestral suite led to a number of other arrangements, including an arrangement of the full ballet for orchestra in 1954 and an arrangement of the "Simple Gifts" variations for band and later orchestra (1956 and 1967, respectively). In total, five versions of Appalachian Spring exist as created by Copland: the original ballet for 13 instruments, the suite for orchestra, a revised version of the ballet for 13 instruments, the revised ballet for orchestra, and the suite for 13 instruments.[i] The orchestral suite remains the most well-known.[148]

Recordings

The first recording of Appalachian Spring was of the orchestral suite: the 1945 premiere of the suite by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra was recorded and reissued in 1999. The ballet for full orchestra was first recorded by the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1954, and Columbia Records released it four years later. The first recording of the original ballet was made in 1990 by Andrew Schenck and Hugh Wolff.[153] In 1958, a video recording of the ballet was made with Graham in the lead roll. The film was financed by WQED, who had already produced one successful Graham film. Nathan Kroll, a musician who had a good understanding of the score, directed the film and consulted Louis Horst (the conductor of the premiere) to ensure the music was just as Copland wanted.[153][154] Another version was made in 1976 for WNET's Dance in America film series, with Yuriko in the leading role.[61][155] The choreography of both versions remained close to the original.[156] As of 2023,[update] there over 150 available commercial recordings of Appalachian Spring.[157]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ In the final scenario, the exact time period is left ambiguous to the entire 19th century.[38]

- ^ See Crist (2005, p. 168) for a table comparison of differences between the "Name" scripts and the final Appalachian Spring scenario.

- ^ Copland turned "Ballet for Martha" into the subtitle of the work.[37]

- ^ The bridge in question is the Brooklyn Bridge in New York.[53]

- ^ See a picture of the statue at the Museum of Modern Art's website.

- ^ For the sake of consistency, this article will use these new names from now on.

- ^ Appalachian Spring premiered alongside two other Coolidge commissions: Hérodiade, set to music by Hindemith, and Imagined Wing, set to music titled Jeux de Printemps by Milhaud.[81]

- ^ In her 1991 autobiography, Graham actually claimed that she heard the tune in a cathedral and asked Copland to include it in Appalachian Spring.[117]

- ^ This list is chronological.

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f Pollack 2013, 1. Life.

- ^ a b Oja & Tick 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 15, 20.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 27.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Ross 2007, p. 291.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 43.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 48.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 72–73, 75.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 91–92, 103.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 291–292.

- ^ a b c d e Philip 2018, p. 182.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 89–90.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 292–293.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 113.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 297.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 302–303.

- ^ Copland & Perlis 1984, p. 245.

- ^ Dickinson, Peter (2016). "Charles Ives and Aaron Copland". Peter Dickinson: Words and Music (1 ed.). Boydell & Brewer. p. 80. doi:10.1017/9781782046660.006. ISBN 978-1-78204-666-0. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 300.

- ^ a b Oja & Tick 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 320, 322.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 362.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 389.

- ^ Teachout, Terry (June 8, 1998). "The Dancer Martha Graham". Time. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e Pollack 1999, p. 391.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Philip 2018, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Pollack 1999, p. 392.

- ^ Graham 1991, p. 226.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 50.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 167.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 393.

- ^ a b Oja & Tick 2005, p. 140.

- ^ a b Franko 2012, p. 51.

- ^ a b Ross 2007, p. 329.

- ^ a b Stodelle 1984, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d Pollack 1999, p. 394.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Graham 1991, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Franko 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pollack 1999, p. 395.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 329–330.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 395–396.

- ^ a b c Philip 2018, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e Pollack 1999, p. 396.

- ^ a b c Ross 2007, p. 330.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 211.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 401.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 216–217.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 216.

- ^ Graham 1991, p. 223.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 47.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 154–155.

- ^ Stodelle 1984, p. 154–155.

- ^ a b c d Jowitt, Deborah (1998). "Appalachian Spring". In Cohen, Selma Jeanne (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Dance. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Simmons, Patricia (January 24, 1945). "Second Concert of Season for Graham Group". Evening Star. p. 15. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 221.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 402.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 402–403.

- ^ Philip (2018, p. 183) quoting Pollack (1999, p. 393).

- ^ a b c d Pollack 1999, p. 404.

- ^ Oja & Tick 2005, p. 137.

- ^ Simmons, Patricia (October 31, 1944). "Graham Group Dances Trio of New Works". Evening Star. p. 25. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b de Mille 1991, p. 261.

- ^ Robinson, Emily (April 8, 2019). "When Autumn in D.C. Felt Like an Appalachian Spring". Boundary Stones. WETA. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ de Mille 1991, p. 262, 510.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 62–63.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 154.

- ^ a b Cochrane, Robert B. (November 1, 1944). "Festival of Chamber Music". The Baltimore Sun. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Evans, Lee (May 20, 1945). "Vivid Impressions Are Made By Latest Graham Dances". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 35. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Martin, John (May 15, 1941). "Graham Dancers Open at National: Appalachian Spring Premiere Feature of First of Seven Programs by Troupe". The New York Times. p. 23. ProQuest 107299477.

- ^ Kastendieck, Miles (May 15, 1945). "Martha Graham Introduces Appalachian Spring in Opening at the National". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 15. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ W., P. (January 28, 1945). "The Dance". The Boston Globe. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martha Graham in New Triumphs in New York". Santa Barbara News-Press. June 10, 1945. p. 8. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Appalachian Spring". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on February 21, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 391, 404.

- ^ Stodelle 1984, p. 129.

- ^ Copland, Crist & Shirley 2008, p. 164.

- ^ Martin, J. (October 8, 1944). "Announcement of a Performance of Martha Graham's Commission by the Coolidge Foundation". The New York Times (PDF). Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c Lunden, Jeff (November 13, 2000). "Appalachian Spring". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Stodelle 1984, p. 130.

- ^ a b Martin, John (November 1, 1944). "Graham Dancers in Festival Finale: Repeat Earlier Performance of Three New Works on the Library of Congress Stage". The New York Times. p. 19. ProQuest 106763600.

- ^ Terry, Walter (1978). Wentink, Andrew Mark (ed.). I Was There: Selected Dance Reviews and Articles, 1936-1976. The Dance Program. New York: Marcel Dekker. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-8247-6524-8.

- ^ Copland, Crist & Shirley 2008, p. 170.

- ^ "Graham Program To Be Repeated". Evening Star. October 26, 1944. p. 34. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Martin, John (January 14, 1945). "The Dance; American Trio – Other Events". The New York Times. pp. X4. ProQuest 107354492.

- ^ Oja & Tick 2005, p. 135.

- ^ Ross 2007, p. 404.

- ^ Martin, John (May 17, 1945). "Graham Dancers Offer a Novelty: John Brown Seen at National, With Erick Hawkins and Will Hare in the Cast". The New York Times. p. 15. ProQuest 107238616.

- ^ Allen, Erin (October 9, 2014). "Documenting Dance: The Making of 'Appalachian Spring'". Library of Congress Blogs. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Spiegel, Jan Ellen (October 11, 1998). "Dance; Appalachian Spring Finds Renewal in the Rockies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Tim (April 7, 2013). "'Appalachian Spring' Training". The Baltimore Sun. pp. E1, E7. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mark, Steven (February 25, 2011). "Copland Revisited: A New Choreography of 'Appalachian Spring' Has the Ballet in a New Milieu". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. p. 79. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stumpfl, Amy (March 6, 2016). "Nashville Ballet Season Includes Fresh Looks at Familiar Stories". The Tennessean. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Bongiovanni, Domenica (May 31, 2018). "Indy Dancers Are Presenting 'Appalachian Spring'". The Indianapolis Star. pp. A18. Retrieved August 18, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Sarasota Ballet Returns With New World". The Ballet Herald. October 7, 2021. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c Crist 2005, p. 176.

- ^ a b de Mille 1991, p. 262.

- ^ Robertson 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 210–211.

- ^ Oja & Tick 2005, p. 140–141.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 210.

- ^ Oja & Tick 2005, p. 141.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 403.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d Crist 2005, p. 172.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 47–48.

- ^ a b c Oja & Tick 2005, p. 138.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 400.

- ^ Franko 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Graham 1991, p. 105.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 398, 401.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 218.

- ^ a b Salas, Juan Orrego (Autumn 1948). "Aaron Copland: A New York Composer". Tempo (9): 16. doi:10.1017/S004029820005395X. ISSN 0040-2982. S2CID 143496980. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Pollack 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Copland, Crist & Shirley 2008, p. 157.

- ^ "Appalachian Spring: Complete Ballet for 13 Instruments, As Premiered by Martha Graham in 1944". Aaron Copland. October 7, 2019. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Appalachian Spring Suite: Version for 13 Instruments". Aaron Copland. July 16, 2019. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Appalachian Spring Suite: Version for Orchestra". Aaron Copland. July 16, 2019. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Appalachian Spring: Newly Completed Orchestration of the Full Ballet, 2016". Aaron Copland. October 9, 2019. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 171–172.

- ^ Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 220.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Pollack 1999, p. 397.

- ^ Robertson 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 397–398.

- ^ a b c Rutkoff & Scott 1995, p. 222.

- ^ a b Thomas 1995, p. 157.

- ^ Robertson 1999, p. 11, 13.

- ^ Robertson 1999, p. 13, 15.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 156–157.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 161.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 398–399.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 174.

- ^ a b c Pollack 1999, p. 399.

- ^ Crist 2005, p. 174–175.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 160.

- ^ a b Crist 2005, p. 175.

- ^ Pollack 1999, p. 404–405.

- ^ Downes, Olin (October 5, 1945). "Rodzinski Offers Music of Copland: Appalachian Spring Heard as Philharmonic Opens Its 104th Season". The New York Times. p. 27. ProQuest 107240373.

- ^ "Events in the World of Music". The New York Times. July 1, 1945. p. 24. ProQuest 107151517.

- ^ a b Pollack 1999, p. 405.

- ^ "Events in the World of Music". The New York Times. November 18, 1945. p. 50. ProQuest 107065750.

- ^ "Abravanel Concert Tour: Conductor Off on Plane to Pay Australia a Visit". The New York Times. December 28, 1945. p. 21. ProQuest 107381676.

- ^ Martin, John (January 22, 1946). "Martha Graham Opens New Season: Dancer Starts 2-Week Run at the Plymouth in Impressive Fashion--3 Works Offered". The New York Times. p. 37. ProQuest 107690192.

- ^ "It Happens in the World of Music". The New York Times. May 19, 1946. pp. X5. ProQuest 107787764.

- ^ a b Delapp-Birkett, Jennifer (August 29, 2022). "Midday Thoughts: Which Appalachian Spring? An Audiophile's Guide". Aaron Copland. Archived from the original on July 30, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ de Mille 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 150.

- ^ Thomas 1995, p. 152.

- ^ "Copland: Appalachian Spring". Presto Classical. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

Sources

- Copland, Aaron; Perlis, Vivian (1984). Copland 1900 Through 1942. New York: St. Martins/Marek. ISBN 978-0-312-16962-6.

- Copland, Aaron; Crist, Elizabeth B.; Shirley, Wayne (2008). The Selected Correspondence of Aaron Copland. New Haven: Yale University Press. doi:10.12987/9780300133479. ISBN 978-0-300-11121-7. JSTOR j.ctt1nq05k.

- Crist, Elizabeth (2005). Music for the Common Man: Aaron Copland During the Depression and War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538359-1.

- de Mille, Agnes (1991). Martha: The Life and Work of Martha Graham (1st ed.). London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-175219-4.

- Franko, Mark (2012). "2. Politics Under Erasure: Regionalism as Cryptology". Martha Graham in Love and War: The Life in the Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-0-19-977766-2.

- Graham, Martha (1991). Blood Memory. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-26503-4.

- Oja, Carol J.; Tick, Judith, eds. (2005). Aaron Copland and His World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12470-4.

- Philip, Robert (2018). "Aaron Copland (1900–90)". The Classical Music Lover's Companion to Orchestral Music. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 182–190. ISBN 978-0-300-24272-0.

- Pollack, Howard (1999). Aaron Copland. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-4909-1.

- Pollack, Howard (2013). "Aaron Copland". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2249091. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription required)

- Robertson, Marta (Spring 1999). "Musical and Choreographic Integration in Copland's and Graham's "Appalachian Spring"". The Musical Quarterly. 83 (1). Oxford University Press: 6–26. doi:10.1093/mq/83.1.6. JSTOR 742256.

- Ross, Alex (2007). The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-312-42771-9.

- Rutkoff, Peter M.; Scott, William B. (October 1995). "Appalachian Spring: A Collaboration and a Transition". Prospects. 20: 209–225. doi:10.1017/S0361233300006062.

- Stodelle, Ernestine (1984). Deep Song: The Dance Story of Martha Graham. London: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-872520-8.

- Thomas, Helen (1995). "Appalachian Spring". Dance, Modernity and Culture: Explorations in the Sociology of Dance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08793-3.

External links

- Ballets by Martha Graham

- Ballets by Aaron Copland

- Compositions by Aaron Copland

- Music commissioned by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge

- Pulitzer Prize for Music-winning works

- 1944 ballet premieres

- Ballets with sets by Isamu Noguchi

- 1944 compositions

- Orchestral suites

- Compositions for chamber orchestra

- Works based on Simple Gifts

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- Ballets set in Pennsylvania