Transistor radio

A transistor radio is a small portable radio receiver that uses transistor-based circuitry. Following the invention of the transistor in 1947—which revolutionized the field of consumer electronics by introducing small but powerful, convenient hand-held devices—the Regency TR-1 was released in 1954 becoming the first commercial transistor radio. The mass-market success of the smaller and cheaper Sony TR-63, released in 1957, led to the transistor radio becoming the most popular electronic communication device of the 1960s and 1970s. Transistor radios are still commonly used as car radios. Billions of transistor radios are estimated to have been sold worldwide between the 1950s and 2012.[citation needed]

The pocket size of transistor radios sparked a change in popular music listening habits, allowing people to listen to music anywhere they went. Beginning around 1980, however, cheap AM transistor radios were superseded initially by the boombox and the Sony Walkman, and later on by digitally-based devices with higher audio quality such as portable CD players, personal audio players, MP3 players and (eventually) by smartphones, many of which contain FM radios.[1][2] A transistor is a semiconductor device that amplifies and acts as an electronic switch.

Background

Before the transistor was invented, radios used vacuum tubes. Although portable vacuum tube radios were produced, they were typically bulky and heavy. The need for a low voltage high current source to power the filaments of the tubes and high voltage for the anode potential typically required two batteries. Vacuum tubes were also inefficient and fragile compared to transistors and had a limited lifetime.

Bell Laboratories demonstrated the first transistor on December 23, 1947.[3] The scientific team at Bell Laboratories responsible for the solid-state amplifier included William Shockley, Walter Houser Brattain, and John Bardeen[4] After obtaining patent protection, the company held a news conference on June 30, 1948, at which a prototype transistor radio was demonstrated.[5]

There are many claimants to the title of the first company to produce practical transistor radios, often incorrectly attributed to Sony (originally Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation). Texas Instruments had demonstrated all-transistor AM (amplitude modulation) radios as early as May 25, 1954,[6][7] but their performance was well below that of equivalent vacuum tube models. A workable all-transistor radio was demonstrated in August 1953 at the Düsseldorf Radio Fair by the German firm Intermetall.[8] It was built with four of Intermetall's hand-made transistors, based upon the 1948 invention of the "Transistor"-germanium point-contact transistor by Herbert Mataré and Heinrich Welker. However, as with the early Texas Instruments units (and others) only prototypes were ever built; it was never put into commercial production. RCA had demonstrated a prototype transistor radio as early as 1952, and it is likely that they and the other radio makers were planning transistor radios of their own, but Texas Instruments and Regency Division of I.D.E.A., were the first to offer a production model starting in October 1954.[9]

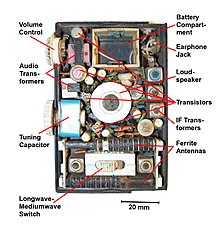

The use of transistors instead of vacuum tubes as the amplifier elements meant that the device was much smaller, required far less power to operate than a tube radio, and was more resistant to physical shock. Since the transistor's base element draws current, its input impedance is low in contrast to the high input impedance of the vacuum tubes.[10] It also allowed "instant-on" operation, since there were no filaments to heat up. The typical portable tube radio of the fifties was about the size and weight of a lunchbox and contained several heavy, non-rechargeable batteries—one or more so-called "A" batteries to heat the tube filaments and a large 45- to 90-volt "B" battery to power the signal circuits. By comparison, the transistor radio could fit in a pocket and weighed half a pound or less, and was powered by standard flashlight batteries or a single compact battery. The 9-volt battery was introduced for powering transistor radios.[citation needed]

Early commercial transistor radios

Regency TR-1

Two companies working together, Texas Instruments of Dallas, and Industrial Development Engineering Associates (I.D.E.A.) of Indianapolis, Indiana, were behind the unveiling of the Regency TR-1, the world's first commercially produced transistor radio. Previously, Texas Instruments was producing instrumentation for the oil industry and locating devices for the U.S. Navy and I.D.E.A. built home television antenna boosters. The two companies worked together on the TR-1, looking to grow revenues for their respective companies by breaking into this new product area.[5] In May 1954, Texas Instruments had designed and built a prototype and was looking for an established radio manufacturer to develop and market a radio using their transistors. (The Chief Project Engineer for the radio design at Texas Instruments' headquarters in Dallas, Texas was Paul D. Davis Jr., who had a degree in Electrical Engineering from Southern Methodist University. He was assigned the project due to his experience with radio engineering in World War II.) None of the major radio makers including RCA, GE, Philco, and Emerson were interested. The President of I.D.E.A. at the time, Ed Tudor, jumped at the opportunity to manufacture the TR-1, predicting sales of the transistor radios at "20 million radios in three years".[11] The Regency TR-1 was announced on October 18, 1954, by the Regency Division of I.D.E.A., was put on sale in November 1954 and was the first practical transistor radio made in any significant numbers.[12] Billboard reported in 1954 that "the radio has only four transistors. One acts as a combination mixer-oscillator, one as an audio amplifier, and two as intermediate-frequency amplifiers."[13] One year after the release of the TR-1 sales approached the 100,000 mark. The look and size of the TR-1 were well received, but the reviews of the TR-1's performance were typically adverse.[11] The Regency TR-1 was patented[14] by Richard C. Koch, former Project Engineer of I.D.E.A.

Raytheon 8-TP-1

In February 1955, the second transistor radio, the 8-TP-1, was introduced by Raytheon. It was a larger portable transistor radio, including an expansive four-inch speaker and four additional transistors (the TR-1 used only four). As a result, the sound quality was much better than the TR-1. An additional benefit of the 8-TP-1 was its efficient battery consumption. In July 1955, the first positive review of a transistor radio appeared in the Consumer Reports that said, "The transistors in this set have not been used in an effort to build the smallest radio on the market, and good performance has not been sacrificed."

Following the success of the 8-TP-1, Zenith, RCA, DeWald, Westinghouse, and Crosley began flooding the market with additional transistor radio models.[11]

Chrysler Mopar 914HR

Chrysler and Philco announced that they had developed and produced the world's first all-transistor car radio in the April 28th 1955 edition of the Wall Street Journal.[15] Chrysler made the all-transistor car radio, Mopar model 914HR, available as an "option" in fall 1955 for its new line of 1956 Chrysler and Imperial cars, which hit the showroom floor on October 21, 1955. The all-transistor car radio was a $150 option (equivalent to $1,710 in 2023).[16][17][18][19]

Japanese transistor radios

While on a trip to the United States in 1952, Masaru Ibuka, founder of Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation (now Sony), discovered that AT&T was about to make licensing available for the transistor. Ibuka and his partner, physicist Akio Morita, convinced the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) to finance the $25,000 licensing fee (equivalent to $286,842 today).[20] For several months Ibuka traveled around the United States borrowing ideas from the American transistor manufacturers. Improving upon the ideas, Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation made its first functional transistor radio in 1954.[11] Within five years, Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation grew from seven employees to approximately five hundred.[citation needed]

Other Japanese companies soon followed their entry into the American market and the grand total of electronic products exported from Japan in 1958 increased 2.5 times in comparison to 1957.[21]

Sony TR-55

In August 1955, while still a small company, Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation introduced their TR-55 five-transistor radio under the new brand name Sony.[22][23] With this radio, Sony became the first company to manufacture the transistors and other components they used to construct the radio. The TR-55 was also the first transistor radio to utilize all miniature components. It is estimated that only 5,000 to 10,000 units were produced.[citation needed]

Sony TR-63

The TR-63 was introduced by Sony to the United States in December 1957. The TR-63 was 6 mm (1⁄4 in) narrower and 13 mm (1⁄2 in) shorter than the original Regency TR-1. Like the TR-1 it was offered in four colors: lemon, green, red, and black. In addition to its smaller size, the TR-63 had a small tuning capacitor and required a new battery design to produce the proper voltage. It used the nine-volt battery, which would become the standard for transistor radios. Approximately 100,000 units of the TR-63 were imported in 1957.[11] This "pocketable" (the term "pocketable" was a matter of some interpretation, as Sony allegedly had special shirts made with oversized pockets for their salesmen) model proved highly successful.[24]

The TR-63 was the first transistor radio to sell in the millions, leading to the mass-market penetration of transistor radios.[25] The TR-63 went on to sell seven million units worldwide by the mid-1960s.[26] With the visible success of the TR-63, Japanese competitors such as Toshiba and Sharp Corporation joined the market. By 1959, in the United States market, there were more than six million transistor radio sets produced by Japanese companies that represented $62 million in revenue.[11]

The success of transistor radios led to transistors replacing vacuum tubes as the dominant electronic technology in the late 1950s.[27] The transistor radio went on to become the most popular electronic communication device of the 1960s and 1970s. Billions of transistor radios are estimated to have been sold worldwide between the 1950s and 2012.[25]

Pricing

Prior to the Regency TR-1, transistors were difficult to produce. Only one in five transistors that were produced worked as expected (only a 20% yield) and as a result the price remained extremely high.[11] When it was released in 1954, the Regency TR-1 cost $49.95 (equivalent to $567 today) and sold about 150,000 units. Raytheon and Zenith Electronics transistor radios soon followed and were priced even higher. In 1955, Raytheon's 8-TR-1 was priced at $80 (equivalent to $910 today).[11] By November 1956 a transistor radio small enough to wear on the wrist and a claimed battery life of 100 hours cost $29.95.[28]

Sony's TR-63, released in December 1957, cost $39.95 (equivalent to $434 today).[11] Following the success of the TR-63 Sony continued to make their transistor radios smaller. Because of the extremely low labor costs in Japan, Japanese transistor radios began selling for as low as $25.[11] By 1962, the TR-63 cost as low as $15 (equivalent to $151 today),[25] which led to American manufacturers dropping prices of transistor radios down to $15 as well.[11]

In popular culture

Transistor radios were extremely successful because of three social forces—a large number of young people due to the post–World War II baby boom, a public with disposable income amidst a period of prosperity, and the growing popularity of rock 'n' roll music. The influence of the transistor radio during this period is shown by its appearance in popular films, songs, and books of the time, such as the movie Lolita.

In the late 1950s, transistor radios took on more elaborate designs as a result of heated competition. Eventually, transistor radios doubled as novelty items. The small components of transistor radios that became smaller over time were used to make anything from "Jimmy Carter Peanut-shaped" radios to "Gun-shaped" radios to "Mork from Ork Eggship-shaped" radios. Corporations used transistor radios to advertise their business. "Charlie the Tuna-shaped" radios could be purchased from Star-Kist for an insignificant amount of money giving their company visibility amongst the public. These novelty radios are now bought and sold as collectors' items amongst modern-day collectors.[29][30][31]

Rise of portable audio players

Since the 1980s, the popularity of radio-only portable devices declined with the rise of portable audio players which allowed users to carry and listen to tape-recorded music. This began in the late 1970s with boom boxes and portable cassette players such as the Sony Walkman, followed by portable CD players, digital audio players, and smartphones.

See also

References

- ^ Petraglia, Dave (5 March 2014). "Why You Owe Your Smartphone To The Transistor Radio". Thought Catalog.

- ^ Bray, Hiawatha (6 November 2014). "Is Your Smartphone Ready for Radio?". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Arns, R.G. (October 1998). "The other transistor: early history of the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor" (PDF). Engineering Science and Education Journal. 7 (5): 233–240. doi:10.1049/esej:19980509. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Handy et al. (1993), p. 13.

- ^ a b "The Revolution in Your Pocket". Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Invention and Technology Magazine, Fall 2004, Volume 20 Issue 2, "The Revolution in your Pocket", Author: Robert J. Simcoe

- ^ Book Title: TI, the Transistor, and Me, Author: Ed Millis, page 34

- ^ Article: "The French Transistor", Author: Armand Van Dormael, page 15, Source: IEEE Global History Network

- ^ website: www.regencytr1.com, Regency TR-1 Transistor Radio History

- ^ Donald L. Stoner & L.A. Earnshaw (1963). The Transistor Radio Handbook: Theory, Circuitry, and Equipment. Editors and Engineers, Ltd. page 32

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k David Lane & Robert Lane (1994). Transistor Radios: A Collector's Encyclopedia and Price Guide. Wallace-Homestead Book Company. pp. 2–7. ISBN 0-87069-712-9.

- ^ Deffree, Suzanne (17 October 2017). "TI announces 1st transistor radio, October 18, 1954". EDN. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Regency markets pocket transistor radio". Billboard. 30 October 1954.

- ^ US 2892931, Koch, Richard C., "Transistor radio apparatus", published 1959-06-30, assigned to IDEA Inc.

- ^ Wall Street Journal, "Chrysler Promises Car Radio With Transistors Instead of Tubes in '56", April 28th 1955, page 1

- ^ Hirsh, Rick. "Philco's All-Transistor Mopar Car Radio". Allpar.com. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Mopar 914-HR Ch= C-5690HR Car Radio Philco, Philadelphia". www.radiomuseum.org.

- ^ "North America | FCA Group". www.fcagroup.com.

- ^ Chrysler Imperial Owners Manual, 1956, Page 13

- ^ "Sony History. Chapter4: Ibuka's First Visit to the United States". Sony.net. Sony. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Handy et al. (1993), pp. 23–29.

- ^ John Nathan (1999). SONY : the private life. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-89327-5. page 35

- ^ "Transistor Radios". ScienCentral. 1999. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ "Sony Global – Sony History". Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ a b c Skrabec, Quentin R. Jr. (2012). The 100 Most Significant Events in American Business: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–7. ISBN 978-0313398636.

- ^ Snook, Chris J. (29 November 2017). "The 7 Step Formula Sony Used to Get Back On Top After a Lost Decade". Inc.

- ^ Kozinsky, Sieva (8 January 2014). "Education and the Innovator's Dilemma". Wired. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "Broadcast Band – All Transistor Wrist Radio". Galaxy (advertisement). November 1956. p. 1. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Handy et al. (1993), pp. 46–51.

- ^ "N.A.". Antique Radio Classified. John V. Terrey. June 2002. p. 10.

- ^ "N.A.". Antique Radio Classified. John V. Terrey. March 2008. p. 6.

- Handy; Erbe; Blackham; Antonier (1993). Made in Japan: Transistor Radios of the 1950s and 1960s. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-0271-X.

Further reading

- Michael F. Wolff: "The secret six-month project. Why Texas Instruments decided to put the first transistor radio on the market by Christmas 1954 and how it was accomplished." IEEE Spectrum, December 1985, pages 64–69

- Transistor Radios: 1954–1968 (Schiffer Book for Collectors) by Norman R. Smith

- Unique books on Transistor Radios by Eric Wrobbel

- The Portable Radio in American Life by University of Arizona professor Michael Brian Schiffer, Ph.D. (The University of Arizona Press, 1991).

- Restoring Pocket Radios (DVD) by Ron Mansfield and Eric Wrobbel. (ChildhoodRadios.com, 2002).

- The Regency TR-1 story, based on an interview with Regency co-founder, John Pies (partner with Joe Weaver) "Regency's Development of the TR-1 Transistor Radio" website

- Bryant & Cones (1995). The Zenith Transoceanic The Royalty of Radios. Schiffer Book for Collectors. Schiffer. pp. 110–120. ISBN 0-88740-708-0.

External links

Media related to Transistor radios at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Transistor radios at Wikimedia Commons- http://www.jamesbutters.com/ Focusing on the history and design elements of early pocket transistor radios.

- "Transistor Radios Around the World"—hundreds of photos and detailed information on early transistor radios from the U.S., Japan, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and the USSR.

- Radio Wallah Historical data accompanied by hundreds of images covering early transistor radios.

- Web site about the first transistor radio by Dr. Steven Reyer, a professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department at the Milwaukee School of Engineering.Category: Transistor

- Regency TR-1 Transistor Radio History: Web site with many historical references on the web and in published literature

- 1954 to 2004, the TR-1's Golden Anniversary. In-depth coverage of the Regency radio.

- The Transistor Radio Directory.

- "GE First Transistor Radio to Smithsonian".

- The First Transistor Radios—1950s, pictured.