The Second World War (book series)

This article contains several duplicated citations. (June 2024) |

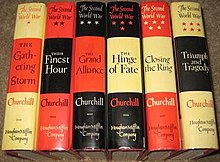

First edition in 6 volumes | |

| Author | Winston Churchill and assistants |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Second World War |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1948–1953 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom[1] |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Liberal Government

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

First Term

Second Term

Books

|

||

The Second World War is a history of the period from the end of the First World War to July 1945, written by Winston Churchill. Churchill labelled the "moral of the work" as follows: "In War: Resolution, In Defeat: Defiance, In Victory: Magnanimity, In Peace: Goodwill".[2]

Churchill wrote the book, with a team of assistants, using both his own notes and privileged access to official documents while still working as a politician; the text was vetted by the Cabinet Secretary. Churchill was largely fair in his treatment, but wrote the history from his personal point of view. He was unable to reveal all the facts, as some, such as the use of Ultra electronic intelligence, had to remain secret. From a historical point of view the book is therefore an incomplete memoir by a leading participant in the direction of the war.

The book was a major commercial success in Britain and the United States. The first edition appeared in six volumes; later editions appeared in twelve and four volumes, and furthermore there is also a single-volume abridged version.

Writing

When Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, he intended to write a history of the war then beginning. He said several times: "I will leave judgements on this matter to history—but I will be one of the historians." To circumvent the rules against the use of official documents, he took the precaution throughout the war of having a weekly summary of correspondence, minutes, memoranda and other documents printed in galleys and headed "Prime Minister's personal minutes". These were then stored at his home and Churchill wrote or dictated letters and memoranda with the intention of placing his views on the record, for later use as a historian. The arrangements became a source of controversy when The Second World War began appearing in 1948. Churchill was a politician, not an academic historian and was Leader of the Opposition, intending to return to office, so Churchill's access to Cabinet, military and diplomatic records denied to other historians was questioned.[3]

It was not known at the time that Churchill had done a deal with Clement Attlee and the Labour government which came to office in 1945. Attlee agreed to allow Churchill's research assistants access to all documents, provided that no official secrets were revealed, the documents were not used for party political purposes and the typescript was vetted by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Norman Brook. Brook took a close interest in the books and rewrote some sections to ensure that British interests were not harmed or the government embarrassed.[4] Churchill's privileged access to documents and his knowledge gave him an advantage over other historians of the Second World War for many years. The books had enormous sales in both Britain and the United States and made Churchill a rich man for the first time.[5][6] The gathered documents were placed in chronologies by his advisers, and this store of material was further supplemented by dictated recollections of key episodes, together with queries about chronology, location and personalities for his team to resolve.[7] Churchill also wrote to many fellow actors requesting documents and comments.[7] Once all was collected and collated, Churchill began writing in earnest, dictating almost all of the work, with the notable exception of several long passages in Volume I.[7]

Themes

As various archives have been opened, several deficiencies of the work have become apparent. Some of these are inherent in the position Churchill occupied as a former prime minister and a serving politician. He could not reveal ongoing military secrets, such as the work of the code breakers at Bletchley Park, or the planning of the atomic bomb.[8] As stated in the author's introduction, the book concentrates on the British war effort.[2] Other theatres of war are described largely as a background.[9] He modified a number of passages when he learnt that General Dwight Eisenhower was to run for the US presidency, removing any remarks which might harm the "special relationship" which he intended to establish (or re-establish) with the new president.[4]

The Gathering Storm

The British historian David Reynolds noted that Churchill in volume one, The Gathering Storm, skipped over the 1920s as his actions in the 1920s did not support his self-image as a far-sighted leader who was aware of the threat from the Axis states. Churchill criticised the "follies" of the victors of 1918 in drafting the Treaty of Versailles, which he viewed as too harsh towards Germany, but then contradictorily defended the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles under the grounds that if the Reich had remained disarmed, the Second World War would never had happened.[10] Churchill defended the foreign policy of the second Baldwin government-in which he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in-which sought to revise the Treaty of Versailles in favour of Germany as promoting peace.[11] The decisive moment for Churchill was the 1929 British general election, which was won by the Labour Party under Ramsay MacDonald, which he portrayed as the moment that British foreign policy went off the rails.[12] Reynolds noted that Churchill did not mention that during his time as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1924 to 1929 he had fought for greater social spending to combat the appeal of the British Communist Party to the British working class by cutting defence spending.[13] In the decade or so after the Russian Revolution, Churchill saw Soviet Russia as the principle enemy, but he viewed the Soviet challenge to Britain as ideological, not military. In December 1924 Churchill dismissed any prospect of a war with Japan as he told the prime minister Stanley Baldwin at a cabinet meeting: "A war with Japan! I do not believe there is the slightest chance of that in our lifetime".[14] Accordingly, Churchill argued that the budget for the Royal Navy should be cut as Japan was the only naval power capable of challenging British power in Asia and the reduced expenditure should be used for social programmes.[15] Churchill portrayed himself in The Gathering Storm, as being in the political "wilderness" in the 1930s because of his opposition to the appeasement of Nazi Germany, but in fact the real reason for Churchill being in the "wilderness" was his opposition to the Government of India Act which devolved much power to the Indians as a preparatory step towards ending the Raj.[16] Alongside his absolute opposition towards any measure that would weaken the Raj, Churchill had led a backbenchers rebellion in 1930-1931 with the aim of toppling Baldwin (who supported the Government of India Act) as the leader of the Conservative Party, which to his exclusion from the cabinet when the National Government was formed in 1931.[17] Reynolds noted that the impression given in The Gathering Storm was Churchill was sent out to the "political wilderness" for his prescient warnings about Nazi Germany when in fact the reason for his being on the political margins was that he had been very disloyal towards Baldwin who understandably did not want a man who had tried to depose him as Tory leader in the cabinet.[18]

Churchill portrayed Anthony Eden-who served twice as his Foreign Secretary in 1940-1945 and again in 1951-1955-as an especially noble anti-appeaser when in fact he regarded Eden in the 1930s as both a political lightweight prone to excessive ambition and bad judgement and until 1938 as an appeaser.[19] At Eden's request, Churchill rewrote several chapters to portray Eden-who supported appeasement until 1938-as being an anti-appeaser during his first time as Foreign Secretary between 1935 to 1938.[20] Churchill portrayed Eden's resignation from the Chamberlain cabinet in February 1938 as the decisive turning point under which the appeaser Lord Halifax became Foreign Secretary.[21] This account was written to please Eden, who had been seen as Churchill's "heir apparent" since 1940, as Eden wanted to remembered as an anti-appeaser who had resigned in protest against Neville Chamberlain's foreign policy.[22] In fact, Churchill did not regard the replacement of Eden with Halifax at the time as marking any important change.[23] Eden who had first met Adolf Hitler in 1935 very much liked and admired Hitler whose foreign policy he felt was limited to revising the Treaty of Versailles, an aspect of his life that he wanted erased in the late 1940s as he waited with a barely veiled impatience for Churchill to retire as Conservative leader.[24] However, it was true that Eden favored a tougher line against Benito Mussolini, a man whom Eden detested as much as liked Hitler, and it was over foreign policy disagreements over Italy, not Germany, that prompted his resignation from the cabinet in February 1938.

Churchill had a strong belief in the power of strategical bombing to win wars and in a speech in the House of Commons on 28 November 1934 predicted that a Luftwaffe strategical bombing against London would kill between 30,000-40, 000 Londoners in the first week and in July 1936 claimed that a single Luftwaffe bombing raid on London would kill at least 5, 000 people.[25] In reality, German strategical bombing of British cities killed or wounded about 147, 000 people between 1939-1945 and the major problem was less people being killed by bombing, but rather the homelessness caused by the destruction of houses and apartments.[26] Churchill admitted in The Gathering Storm that he made exaggerated claims about the killing capacity of Luftwaffe strategical bombing against British cities as a means to spur the government to spend more on the Royal Air Force (RAF).[27] The British historian David Dutton wrote that the popular image of British politics in the 1930s is of an epic feud between Churchill the anti-appeaser vs. Chamberlain the arch-appeaser, but the real target in The Gathering Storm is not Chamberlain, but rather Baldwin, a man who Churchill greatly hated.[28] The "Churchill Camp" of anti-appeasers consisted of Churchill, Brendan Bracken, Admiral Roger Keyes, Lord Lloyd, and Leo Amery, and because it was so small was not considered a threat by Chamberlain to his ministry. Dutton noted that after the failed attempt to depose him in 1930-1931 that Baldwin always made it clear he would never allow Churchill to serve in the cabinet again while Chamberlain allowed Churchill to join his cabinet on 3 September 1939 by making him First Lord of the Admiralty again.[29] Dutton noted that Chamberlain gave Churchill's career a major boost as it was the popular perception that Churchill was a successful First Lord of the Admiralty in 1939-1940 that allowed Churchill to become Prime Minister, on 10 May 1940, which explained why Churchill was much more savage in his treatment of Baldwin than Chamberlain.[30] Churchill had a chequered record as a politician who was associated with failures, most notably the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, and it the perception that Churchill was an effective First Lord in 1939-1940 that allowed him to be considered as a potential prime minister. In The Gathering Storm, Churchill turned Baldwin "man of Middle England" image against him to devastating effect as he portrayed Baldwin as a petty and provincial politician unfit to be prime minister.[31] As the Conservative leader, Baldwin had been often been photographed in rural settlings, dressed as a squire and smoking his pipe, which was meant to associate him with Deep England, a positive image that Churchill turned into a negative one by writing that Baldwin was too provincial to conduct a proper foreign policy.[32] Dutton wrote that the popular belief that Churchill became Prime Minister because he was an anti-appeaser is not true, and the real reason was the widespread belief that Chamberlain was an unsuccessful war leader as shown by the failure of the Norway expedition while Churchill was seen as the best man to win the war. It was after the publication of the best-selling book Guilty Men in early July 1940 that appeasement started to be seen as a disastrous foreign policy.[33] Chamberlain resigned as prime minister on 8 May 1940 because of the failure of the Norway expedition, and the major issue in May 1940 was who was the best man to win the war, not over appeasement.

In the chapter on the development of radar, Churchill downplayed the role of Sir Henry Tizard while playing up the role of his science adviser Lord Cherwell, aka "The Prof".[34] Churchill wrote Lord Cherwell was fired by Tizard from the Scientific Air Defence Committee in 1937 for being his friend, but in reality Tizard fired Cherwell for his impassioned advocacy of the impractical weapon of "aerial mines", which made Cherwell a disruptive force on the committee.[35] Lord Cherwell served as Churchill's science adviser throughout the war, and Churchill found it embarrassing that some of Cherwell's ideas were those of a crank.[36] In a note he sent to research assistant Bill Deakin on 30 June 1947, Churchill asked: "Surely there was some fighting in 1931 between Japan and China?"[37] Churchill gave only very brief mentions of the crisis in Asia caused by Japan's invasion of China in 1937 along increasing strident Japanese claims that all of Asia should be in the Japanese sphere of influence, which gave a distorted picture of British politics as the government of Neville Chamberlain was highly concerned about the prospect of Japan taking advantage of a war in Europe to seize Britain's colonies in Asia.[38] Despite support for strategical bombing, Churchill judging by his "Memorandum on Sea-power" written on 25 March 1939 did not see air attacks on naval ships as a major danger and he likewise wrote that any threat of submarines had been "mastered".[39] The major theme in Churchill's memo which was based on his experience as the former First Lord of the Admiralty was that naval warfare would be decided in the traditional fashion in gunnery duels between battleships.[40] In the same memo, Churchill assumed that Italy would enter any war on the side of Germany and argued the Royal Navy to focus on the Mediterranean Sea at the expense of Asia.[41] In the "Memorandum on Sea-power", Churchill assumed that Japan would also enter the war on the Axis side, but dismissed the need to activate Singapore strategy under the grounds that the Japanese could never take Singapore.[42] Churchill printed the "Memorandum on Sea-Power" in The Gathering Storm, but cut out the parts where he wrote that Singapore would be "easy" to hold against the Japanese; that there was no threat from U-boats to British shipping; and that aircraft from the Axis nations were not capable of sinking British warships.[43]

Churchill felt very strongly that it would had been better for Britain to go to war in 1938 during the Sudetenland crisis for Czechoslovakia rather than in 1939 during the Danzig crisis for Poland, which was reflected in his account of the two crises.[44] During the Danzig crisis, Churchill believed that a "Grand Alliance" of Britain, France and the Soviet Union would had deterred Hitler from invading Poland, and in The Gathering Storm strongly criticised Neville Chamberlain for believing that Poland was the stronger ally than the Soviet Union.[45] Churchill felt that Chamberlain should tried harder to reach an alliance with the Soviet Union in 1939, which he believed would had prevented World War Two.[46] The principle problem during the talks for the "peace front" in 1939 was that the Soviets kept insisting on transit rights for the Red Army into Poland, which the Poles absolutely refused to cede. Reynolds noted that during the Danzig crisis that British leaders first confronted in embryonic form a recurring problem during Churchill wartime premiership, namely it was not really possible to be both an ally of Poland and the Soviet Union at the same time, and that a choice had to be made.[47] Reynolds noted that "many historians" tended to agree with Churchill's comparison of the Sudetenland crisis with the Danzig crisis, and feel that Churchill was correct in arguing that it would had been far better to go to war for Czechoslovakia in 1938 rather than for Poland in 1939.[48]

Reflecting the "Great Man" view of history, reviewers noted that Churchill gave readers the picture of "an almost stationary world upset by the wild ambitions of a few wicked men", which also reflected the politics of the Cold War.[49] In the Cold War, Churchill saw the principle enemy as the Soviet Union and envisioned West Germany, Italy and Japan as British allies, which led him to portray the origins of World War Two in very personalised terms as due to the "wickedness" of leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. Churchill wrote in an almost admiring tone that Mussolini was one of the exceptional leaders able to blend history to his will, and portrayed Il Duce as a man who perverted Italian politics by preventing the "normal" course of Italian history from occurring.[50] Likewise, Churchill portrayed Hitler very much as a "Great Man" able to blend history to his will owning to his determination and intelligence, which suggests that Nazism was only Hitlerism, and that if Hitler had never lived, there would have been no Nazi Germany as German history would continue on as "normal".[51] Churchill tended to downplay continuities in German history as the imperialistic war aims held by the leaders of the Reich towards both Western Europe and Eastern Europe during the First World War and the absolute refusal to accept the borders with Poland imposed by the Treaty of Versailles during the Weimar Republic. In the Cold War, Churchill supported West German rearmament and as such he portrayed the Wehrmacht in a relatively favorable light, which reflected his viewpoint of West Germany as an ally against the Soviet Union.[52] Churchill tended to portray the Wehrmacht generals more as victims of Hitler rather than his followers, and presented as fact the self-serving claims made by Wehrmacht generals after 1945 that during the Sudetenland crisis of 1938 that they would had staged a military coup to overthrow Hitler, which was prevented by the Munich Agreement.[53] Churchill was informed by his research assistants that these claims being made by the Wehrmacht generals were dubious at best, and were clearly meant to be a rationalisation for serving the Nazi regime with the implication that it was the British and French governments by signing the Munich Agreement who were responsible for them serving Hitler rather than themselves.[54] Churchill wanted to present in The Gathering Storm the thesis that if only he had been prime minister in 1938, the Second World War would have been avoided altogether, which led him to accept at face value the claims of the Wehrmacht generals that they were set upon deposing Hitler in 1938 along with their claims to be "prisoners" of Hitler after the Munich Agreement.[55]

Their Finest Hour

Reynolds likewise noted Churchill sometimes engaged in national stereotypes. In his account of his summit with the French Premier Paul Reynaud on 16 May 1940, Churchill portrayed Reynaud along with Maurice Gamelin and Édouard Daladier as hopelessly defeatist figures which in turn reflected the faiblesse of France, which he used in contrast to the fighting spirit and courage of the British.[56] Reynolds noted that the actual transcript of the Anglo-French summit showed that Gamelin was indeed depressed as Churchill portrayed him, but that Reynaud and Daladier-though worried by the German victory in the Second Battle of Sedan-were no-where near as defeatist as Churchill portrayed them.[57] The British historian Max Hastings noted that the picture that Churchill painted in Their Finest Hour of a British people solidly united under his leadership for a victory over Nazi Germany was not true, and in May-June 1940 much of the British aristocracy along with a number of MPs favoured making peace with Germany under the grounds that the Reich was invincible and the best course of action was to make peace with Hitler where there was still time.[58] Hastings wrote the principle differences between the British and French experiences of the war in 1940 was that in France leaders such as Marshal Philippe Pétain, Pierre Laval, and Marshal Maxime Weygand signed an armistice with Germany, a course of action very favoured by a number of 'Establishment' figures such as the former prime minister David Lloyd George, Lord Westminster, and Lord Tavistock, all of whom had openly advocated peace with the Reich as the best way to save the British empire when there was still time.[59] Hastings wrote that Churchill downplayed his own importance in seeking to continue the war in 1940 as he gave the impression that virtually the entire population of the United Kingdom was united behind his leadership when in fact quite a few powerful people in 1940 favoured following the French example and signing an armistice with the Third Reich.[60] Churchill did not mention in Their Finest Hour the intense debate within the Cabinet between 26-28 May 1940 where the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax arguing that France will soon be defeated argued that Britain should make peace with the Reich while there was still time and use Mussolini as a "honest broker" in making peace.[61] Nor did Churchill mention his statement on 26 May 1940 that "if we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies he would jump at it", though he went on to say that he doubted that it was possible to make any sort of reasonable peace with Hitler who had no reason to make concessions given that Germany was winning the war.[62] During the debate, the Labour leaders Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood rejected Halifax's approach, and were joined by Chamberlain..[63] In the first draft of Their Finest Hour, Churchill accused Halifax of being willing to "buy off" Mussolini by ceding to Italy Gibraltar, Malta and the Suez Canal in exchange for working as a meditator and praised Chamberlain and Attlee as "very stiff and tough" in rejecting Halifax's approach.[64] Churchill ultimately dropped all the references to the debate with Halifax while mentioning that Reynaud was willing to make concessions to Mussolini in exchange for brooking peace, thereby drawing a contrast between the French depicted here as craven and cowardly vs. the British depicted as stout and steward.[65] Churchill also given the misleading impression that he wanted in 1940 to fight on until the total destruction of Nazi Germany while in fact he envisioned making sort of negotiated peace with Germany.[66] Churchill wanted the Second World War to end as the First World War had ended. In 1918, when it was clear that the Allies were winning, the leaders of the German Army, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff wanted the Emperor Wilhelm II to abdicate in order to make peace with the Allies as it was felt better to make a disadvantageous peace rather than see the destruction of the Reich. Churchill expected if Britain could have gain the upper hand in the war, the Wehrmacht generals would turn on Hitler than see the total destruction of Germany, and in this way Britain would impose a peace treaty like the Treaty of Versailles that limit German power, but not destroy it.[67] In 1940, Churchill believed that a strategical bombing campaign would impose such stain on the German economy that eventually the Wehrmacht generals would turn against Hitler to make a favorable peace with the United Kingdom, which he did not mention in Their Finest Hour.[68] Churchill also believed in 1940 that the pro-Allied neutrality of President Franklin D. Roosevelt meant that United States would be entering the war later in 1940, which he did not mention in Their Finest Hour because that did not happen.[69]

In the chapter on the Battle of Britain, Churchill celebrated "the few" as he called the pilots of Fighter Command, but said almost nothing about Air Marshal Air Marshal Hugh Dowding, the commander of Fighter Command.[70] About the sacking of Downing shortly after the Battle of Britain had ended, Churchill blamed the civil servants of the Air Ministry as he insisted he fired Dowding reluctantly.[71] Dowding, a shy, modest man was virtually unknown to the British people during the Battle of Britain, and his sacking in November 1940 had attracted little media attention. It was after 1945 that Dowding came to be celebrated as a "quiet hero", hence Churchill's defensive tone about why he fired Dowding.[72] Churchill downplayed the importance of radar in the Battle of Britain largely because it was the Chamberlain government that built the network of radar stations, but devoted an entire chapter to "The Wizard War".[73] "The Wizard War" celebrated two young British scientists, R.V. Jones and Albert Goodwin, as the scientific "wizards" who had "broken the beams" (the radio beams that guided German bombers onto British cities) that was largely based upon notes from Goodwin and Jones.[74]

The Grand Alliance

In order to uphold the unity of the Commonwealth, Churchill did not mention that he had serious disagreements with strategy in the first half of 1941 with the Australian prime minister Robert Menzies and the New Zealand prime minister Peter Fraser, both of whom had major doubts about the wisdom of dispatching Australian and New Zealand soldiers to the defence of Greece in 1941.[75] Menzies and Fraser both paid an extended visit to London in early 1941 to debate strategy with Churchill; Menzies's visit was only briefly mentioned while Fraser's visit was not mentioned at all.[76] Churchill was a very close friend of the Anglophile Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky, which was acknowledged, but rather downplayed as the Soviet Union was the enemy in the Cold War.[77] The intense dispute between Ernest Bevin vs. Lord Beaverbrook over control of the wartime economy, which ended with Lord Beaverbrook being dropped from the cabinet in 1942, was mentioned, but downplayed as the Bevin-Beaverbrook dispute did not present the Churchill cabinet in the best light.[78] In domestic politics, Churchill reserved most of his fire upon Sir Stafford Cripps, the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party, who had angered Churchill during the war by his advocacy of independence for India.[79] Because Clement Attlee was prime minister when the first volumes were being written, Churchill did not mention his disagreements with him over strategical bombing (which Attlee was opposed to) and over plans for a post-war welfare state (which Churchill was opposed to).[80] Because he was out of office from 1929 to 1939, Churchill was frank about the essential weakness of the Singapore strategy, namely Singapore was only a naval base and not the great fortress that it as presented as.[81] About the decision to activate a mini-version of the Singapore strategy by sending out Force Z under the command of Admiral Tom Philips to Singapore, Churchill wrote that that he believed that Force Z would be sufficient to deter Japan, which he admitted was a mistake.[82] Admiral Philips-a convinced "battleship admiral" who had a dismissive attitude towards air power-took Force Z into the South China Sea without air cover to confront a Japanese invasion fleet heading towards Malaya (modern Malaysia), which resulted in Force Z being sunk by Japanese aircraft operating out of French Indochina (modern Vietnam).[83] Churchill initially sought to explain Philips's folly as being due to aircraft having never sunk warships before, only to be told by his research assistants that aircraft had indeed sunk warships before, which led him to exclude that argument from the final draft.[84] Churchill did not mention the memo he received from Admiral Andrew Cunningham after the Battle of Crete in May 1941 saying he never wanted to have Royal Navy warships without air cover again, saying the losses taken by the Royal Navy off Crete due to German and Italian aircraft were unacceptably high..[85] That Churchill had appointed Philips-who described as a "trusted" friend, which presumably meant he was aware of Philips's views about air power-to command Force Z led Churchill to take a defensive tone about the issue in The Grand Alliance.[86] In fact, Churchill had a falling-out with Philips after he had opposed Churchill's plans to send an expedition to Greece, and the decision to appoint Philips to command Force Z seems to have been as a punishment.[87] Churchill suffered much guilt over the death of Philips who went down with the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, which was reflected in the chapter of the destruction of Force Z.[88]

During his time as wartime prime minister, Churchill believed that a strategical bombing campaign against German cities might be sufficient to win the war, and as such had devoted immense sums of money to the Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force.[89] Churchill had been greatly influenced by a 1942 paper by his science adviser Lord Cherwell known as the "dehousing paper".[90] Following the destruction of Coventry by the Luftwaffe on 14-15 November 1940 that left most of the people of Coventry homeless, there had been a fall in productivity in war industries in the Coventry area. Cherwell professed in the "dehousing paper" to have worked out a precise formula based on the experience of Coventry and other British cities if Bomber Command could "dehouse" a sufficient number of German workers by destroying their homes, the resulting decline in productivity would cripple the German economy, and in this way Britain would win the war without fighting any costly battles on land.[91] Lord Cherwell did not mention in his paper that "dehousing" bombing would probably often kill the people living in the said houses to be destroyed.[92] Churchill accepted Lord Cherwell's advice and on 22 February 1942 appointed the single-minded and ruthless Air Marshal Arthur "Bomber" Harris as the new commander of Bomber Command.[93] Churchill in The Second World War books played down his support for strategical bombing as many of the wartime claims made by the RAF leaders as Air Marshal Arthur Harris of Bomber Command that strategical bombing alone could defeat Germany proved to be highly erroneous, and instead portrayed the strategical bombing more as a supplement to the campaigns on land instead of the war-winning campaign that it was envisioned of at the time.[94] In fact, on 21 July 1942 Churchill told the war cabinet that he believed that it was possible to win the war via strategical bombing alone, a claim he repeated to Stalin during his summit in Moscow on 12 August 1942.[95] During the Moscow summit, Churchill referred to the bombing raid on Cologne on 30 May 1942 that destroyed much of the city, and told Stalin he "hoped to shatter twenty German cities as we had shattered Cologne".[96] During the war, the Deputy Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was highly sceptical about the claims being made by Harris and the other "bomber barons", leading to Churchill to Attlee a lengthy memo on 29 July 1942 saying that Britain's only hope of winning the war was via strategical bombing.[97] In the same memo, Churchill wrote that both the British Army and the US Army were hopelessly inferior to the Wehrmacht in every respect and that "it will certainly be several years before British and American land forces will be capable of beating the Germans on even terms in the open field".[98] None of Churchill's wartime statements about winning the war via bombing alone; his hope that every home in Germany would be destroyed or his statements that it was not possible to defeat the Wehrmacht in battle, making the strategical bombing only option were included in The Second World War books .[99] Churchill did not mention that there was a major disagreement in 1944 between the Americans who favoured an "oil plan" of bombing German oil facilities as the best way to cripple the Wehrmacht vs. the RAF who were committed to the "area bombing" of German cities.[100] The omission about the debate between the "oil plan" vs. "area bombing" was to give the impression that there was no alterative to "area bombing", which became controversial after the war.[101] In the same way, Churchill sought to distance himself from the Anglo-American bombing of Dresden between 13-15 February 1945 by including a memo he had written right after the destruction of Dresden saying that such attacks were no longer necessary.[102] Dresden had been regarded as a center of culture and as one of the most beautiful cities in Europe, and the destruction of Dresden was controversial even in February 1945..[103] Reflecting the theme of Anglo-German reconciliation, Churchill did not write much about the Holocaust, which was likely to stir up anti-German feelings.[104] Churchill buried in the endnotes a memo he sent to Eden on 11 July 1944 calling the extermination of the Jews the "greatest crime" ever committed and ordering Bomber Command to bomb the rail-lines to the Auschwitz death camp.[105] Churchill seems to have been embarrassed that the RAF leadership were so obsessed with the "area bombing" of German cities that they claimed it was impossible to bomb Auschwitz and he did not do much to ensure his orders were carried out.[106] Despite Churchill's memo, the RAF never bombed the rail-lines to Auschwitz.[107]

The Hinge of Fate

Reynold noted that Churchill supported the "deal with Darlan" in 1942 under which Admiral François Darlan defected over to the Allied side, bringing with him Algeria and Morocco, and at the time saw Darlan as a better French ally than Charles de Gaulle, which he sought to deny in The Second World War, giving the impression that he always backed de Gaulle.[108] The picture of Darlan varied from volume to volume. In volume 2, Their Finest Hour, Darlan was depicted as a devious and dishonest leader, a corrupt pro-Nazi schemer whose word was unreliable as a justification for the British attack on the French naval base at Mers-el-Kébir in 1940.[109] In volume 3, The Hinge of Fate, Churchill portrayed Darlan as a honorable, but misguided French patriot.[110] In response to several letters from Field Marshal William Slim who was serving as the Governor-General of Australia about the neglect of the campaigns in Burma in the earlier volumes, Churchill devoted an entire chapter in the last volume, Triumph and Tragedy to the "famous Fourteenth Army, under the masterly command of General Slim"..[111]

In the first draft, Churchill had planned to be more critical of Operation Jubilee, the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942 that failed disastrously, but chose not as the man responsible for the raid, Admiral Louis Mountbatten was a powerful man related to the royal family who would had likely sued for libel had the first draft been published.[112] As a result, Churchill simply wrote the raid on Dieppe had failed with no discussion as to why.[113] Mountbatten wrote to Churchill in 1950 that he objected to the statement that 70% of the men of the 2nd Canadian Division had been "lost" at Dieppe as wrote that only 18% of the men of the 2nd Division had been killed (by "losses" Churchill meant all the men killed, wounded or taken prisoner, which would had amounted to 70%).[114] Mountbatten also insisted that Churchill say the Chiefs of Staff had approved the raid, though there was and still is no evidence in support of this claim..[115] On 1 July 1942, a convoy known as Convoy PQ 17 on the highly dangerous "Murmansk run" though Arctic Ocean to the Soviet city of Archangel had its protection withdrawn by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, following erroneous reports that the German battleship Admiral Tirpitz had set sail from its base in the far north of Norway.[116] Without protection, the merchantmen of PQ 17 were defenceless against the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine, and 24 of the 35 merchantmen were sunk with the survivors dying an icy death in Arctic ocean.[117] Churchill seemed rather surprised that Pound had given the order to withdrew the escorts from PQ 17, especially when it emerged that it was not entirely clear if the Admiral Tirpitz had actually set sail or not, and kept looking for some evidence that would excuse Pound's decision to withdrew the escorts.[118] Churchill was sensitive about PQ 17 as he been seeking to ease Pound into retirement since early 1942.[119] By early 1942, Pound was visibly suffering from the brain cancer that was to kill him in 1943, and had much trouble paying attention at meetings, which Churchill had noticed.[120] Churchill was normally quite ruthless about sacking generals, admirals and air marshals who he believed had failed him, but he had a soft spot for Pound, whom he unsuccessfully tried to nudge into retirement.[121] Churchill's defensive tone about PQ 17 was due to the fact that many in the Royal Navy believed that Pound should had been sacked as First Sea Lord in 1942 instead of being allowed to continue to serve until September 1943 despite his failing health.[122]

A passage highly critical of Chiang Kai-shek as a weak man dominated by his scheming wife, Madame Soong Mei-ling, was included in the first draft, but excluded from the published version in order to offend American public opinion as Chiang was a popular figure in the United States.[123] Likewise, Churchill excluded several passages highly critical of General Charles de Gaulle of France and Marshal Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia in order not to damage Anglo-French and Anglo-Yugoslav relations. Churchill removed any mention of his order in June 1944 that de Gaulle should be "shipped to Algiers in chains if necessary. He must not be allowed to enter France".[124] The dispute had been caused by de Gaulle's demand to be allowed take part in the D-Day landings, which was Churchill was opposed to, and he instead misleadingly claimed that de Gaulle had refused to speak on the BBC on the eve of Operation Overlord.[125] Churchill personally disliked de Gaulle, and was dissuaded from adding passages from his wartime memos disparaging de Gaulle as a "combination of Joan of Arc and Clemenceau" who was capable of anything under the grounds that de Gaulle might be president of France again.[126] Churchill did print a memo from 1943 to Eden mentioning that Britain needed a "strong France" under anti-communist leadership to ensure the peace in the post-war world, which was the reason why Churchill tolerated de Gaulle during the war despite his dislike of him.[127] In the same manner Churchill did not mention his wartime view expressed in 1944 that Tito was a "viper" who was only interested in power for himself.[128] By contrast, Churchill was very critical in The Second World War of the leaders of the Polish government-in-exile except for General Władysław Sikorski, and the negative picture he painted of the Polish leaders reflected his difficult wartime relations with the Polish government-in-exile.[129] Churchill wrote "the heroic characteristics of the Polish race must not blind us to their record of folly and ingratitude...the Poles were glorious in revolt and ruin; squalid and shameful in triumph", a remark that was given wide publicity by the Communist government in Warsaw as an example of the anti-Polish feelings of British leaders.[130] Churchill had found the demands from the Polish leaders such as Stanisław Mikołajczyk about restoring Poland's pre-war eastern frontiers to be highly unrealistic, and as causing difficulties in his relations with Joseph Stalin.[131] Churchill expressed his feelings about the Poles in his remark about the Polish "record of folly and ingratitude", a statement that proved to be so controversial that it was removed from subsequent editions of The Gathering Storm.[132] Churchill believed that the Polish claim that the Soviet NKVD had committed the Katyn Forest massacre of 1940 was correct, he found the timing of the allegation in April 1943 to be highly inconvenient as it came at a time when the Red Army was doing the bulk of the fighting against the Wehrmacht.[133] Against the charge that he not done enough to champion the Polish case, Churchill merely stated in The Hinge of Fate that it was impossible to determine in 1943 who had committed the Katyn Forest massacre.[134] Churchill got along well with President Edvard Beneš of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, and his picture of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile was as positive as his picture of the Polish government-in-exile was negative.[135]

During the war, Churchill was incensed by the advice from President Franklin D. Roosevelt that he should grant independence to India, which was reflected in The Hinge of Fate as American meddling in the affairs of the British empire, which Churchill called "idealism at other people's expense".[136] In a blunt passage, Churchill wrote that Roosevelt's comparison of the Indian struggle for independence with the American Revolutionary War was wrong because the 13 colonies deserved independence while India did not.[137] Such criticism was rare as Roosevelt was a beloved figure in the United States, and Churchill did not want to damage Anglo-American "special relationship".[138] Churchill genuinely liked Roosevelt as a man and his books he tended to portray Roosevelt as an excellent president misled by his "bad" advisers such as General George Marshall and Admiral Ernest C. King whose views on grand strategy Churchill did not share.[139] Churchill did not mention that many British leaders had a low opinion of the American military with for example King George VI writing to Churchill in February 1943 after the American defeat in the Battle of Kasserine Pass that the British would "have to do all the fighting" as he felt the Americans were useless in combat.[140] Churchill printed the king's letter in The Hinge of Fate, but excluded his criticism of the US Army which had angered American readers.[141] Churchill praised the combat record of the Indian Army as a validation of the Raj as he wrote that India had played a major role in the British war effort.[142] But at the same time Churchill denounced all the peoples and politicians of India as ungrateful for the Raj.[143] Churchill portrayed the British as having sacrificed and suffered so much for the Indians who never expressed any thanks and kept unreasonably demanding independence.[144] In the first draft, Churchill accused Mahatma Gandhi of being a Hindu fundamentalist who wanted to oppress Muslims and as a pro-Nazi traitor who would had been all too willing to serve as a puppet Maharaja for the Japanese.[145] This passage was removed from the final draft after Churchill was told by Sir Norman Brook that it was false, inflammatory and likely to cause problems in Anglo-Indian relations.[146] The attack on Gandhi was removed, but throughout all of 'The Second World War, Churchill made clear his dislike of Gandhi and the Indian independence movement.[147]

The famous appeal of the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin on 27 December 1941 for the United States to defend Australia from a Japanese invasion was for Churchill almost treason to the British empire, leading Churchill to lash out at Curtin in The Grand Alliance.[148] Churchill claimed that Curtin should had imposed conscription (a politically toxic move for any government in Canberra) instead of asking for American help.[149] Unlike Curtin who ordered the Australian troops serve in Egypt home to defend against the expected Japanese invasion, Fraser agreed to allow the New Zealand troops to stay in Egypt. Churchill praised Fraser for his "loyal" attitude in keeping the New Zealand forces in Egypt while denouncing Curtin for putting the defence of Australia ahead of the defence of Egypt.[150] The Dominion prime minister whom Churchill liked and respected the most was the South African prime minister General Jan Smuts, and it was Smuts who was the Dominion prime minister given the most respectful treatment in The Second World War series.[151] Smuts was portrayed as the wise and benevolent old Boer general, the embodiment of an Afrikaner takhaar (patriarch), who was always giving sound advice. The fact that Smuts supported Churchill's ideas about favouring operations in the Mediterranean at the expense of operations in France was an additional reason for the favorable treatment of him in the series.[152] Of the British Army generals in the war, the one who Churchill liked and respected the most was Field Marshal Harold Alexander, whom Churchill credited with more or less single-handedly stopping the Japanese from following up their conquest of Burma in the spring of 1942 with an invasion of India.[153] Field Marshal Alan Brooke, who served as chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) for most of the war, is barely mentioned in the books and even the few mentions that made of him relate to his command of his division in France in 1940, not as CIGS.[154]

Reflecting his traditional conception of naval war, Churchill devoted entire chapters to the pursuit of the Admiral Graf von Spee in 1939 and the sinking of the Bismarck in 1941, but gave less attention to the campaign against the U-boats despite the fact that the U-boats were far more dangerous than the Admiral Graf von Spee and the Bismarck.[155] In 1938, British farms provided only food to feed 30% of the British people with the food to feed the other 70% coming from abroad upon merchantmen from all over the world, making the United Kingdom very vulnerable to an U-boat induced famine. The sea battles usually fought at night between the "wolf packs" of the U-boats against the Royal Navy destroyers that protected the convoys of merchantmen and tankers were crucially important for the survival of much of the British population, but Churchill did not seem to find the subject very interesting.[156] The only exception, which came across as an exercise in score-settling, was the chapter "The U-boat Paradise" in The Hinge of Fate which described the "second happy time" for the U-boats between January-July 1942 when the U-boats wrecked havoc upon shipping off the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts of the United States.[157] Admiral Ernest J. King, the Anglophobic commander of the U.S Navy refused to adopt the convoy system under the grounds that it was a British invention and likewise refused to have the lights turned off in American cities, thereby making ships at sea perfect targets for the U-boats at night. In "The U-boat Paradise", Churchill grimly noted that the American shipping paid the price in first half of 1942 as the Americans refused to learn from British experiences.[158]

Closing the Ring

During the war Churchill had favoured a Mediterranean strategy arguing that it was the Mediterranean area that was the decisive theatre of the war and was opposed to American plans for an invasion of north-west Europe. For political reasons about the future of the post-war world, Churchill wanted the Allied armies in Italy to advance into Austria and hence into Hungary in order to include as much of Eastern Europe into the Western sphere of influence as Churchill saw the Soviet Union as the future enemy in the post-war world.[159] As such, Churchill devoted more chapters to the campaign in Italy between 1943-1945 than any of the other campaigns in the war, which gave the impression that the Italian campaign was the decisive campaign of the war.[160] It was no accident that Field Marshal Alexander-whom Churchill viewed as the most able of his generals-commanded the 15th Army Group that fought in Italy.[161] Churchill was unable owning to mention one of his principle reasons for seeing Italy as the "soft underbelly" of the Axis, namely the Allies were reading the German codes and that initially Hitler had planned only to hold northern Italy following the German occupation of Italy in September 1943.[162] However following the hard-fought Battle of Salerno in September 1943, which nearly ended in a German victory, Hitler had decided to hold all of Italy.[163] Over the next two years, the Germans fought a skilful defensive campaign in Italy that forced the Allies to expend much blood and treasure on a slow advance up the Italian peninsula.[164] Churchill's "Great Man" picture of Mussolini was to justified working with the regime of General Pietro Badoglio in 1943-1944.[165] The fact that Badolgio had numerous war crimes during the conquest of Ethiopia was not mentioned, nor was Churchill's opposition to bringing into Badolgio's cabinet politicians from the Liberal era such as Count Carlo Sfoza.[166] Churchill's prime concern with the post-war future of Italy was in keeping the Italian Communists out of power, which explained his support for retaining the Italian monarchy and the lack of mention of Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti entering Badolgio's cabinet in March 1944, which saw as a triumph for Soviet interests..[167] Along the same lines, Churchill devoted an entire chapter to the "Islands Lost" as he presented the Dodecanese campaign in September-December 1943 as a great "missed opportunity" that would had allowed the Western Allies to take control of Eastern Europe and thereby prevented the Red Army from advancing west.[168] Throughout the volumes, Churchill consistently presented his Mediterranean strategy as the superior one to the American strategy of seeking the decisive battles in north-west Europe.[169] Churchill considered adding in to Closing the Ring a memo he written on 19 October 1943 in which listed as the main British priorities for 1944 in this order as stopping the movement of British troops out of the Mediterranean; taking Rome; liberating Rhodes to bring Turkey into the war; British landings upon the Dalmatian coast of Yugoslavia with the aim taking a port; and finally at the bottom of the list Operation Overlord, the codename for the Allied liberation of France.[170] Because Operation Overlord turned out to be a far more decisive operation than Churchill believed it would be, he omitted this memo and instead denounced in Closing the Ring the "legend" that he favoured operations in the Mediterranean at the expense of Operation Overlord.[171] In fact, Churchill in the fall of 1943 seemed to have envisioned Operation Overlord as a supplement to the on-going or planned campaigns in Italy and the Balkans.[172] Churchill did not mention a meeting in London on 19 October 1943 where he was warned by Sir Charles Portal, the chief of the RAF, that if the British continued to delay Overlord, then the Americans might abandon their "Europe First" strategy in favour of an "Asia First" grand strategy.[173] Churchill stated he was willing to accept an American switch to an "Asia First" strategy provided that the Americans continued to take part in the strategical bombing campaign against Germany, which Churchill regarded as the principle American contribution to the war effort.[174] Ultimately, Churchill wanted the United States to be engaged in European affairs after the war as a counterweight to the Soviet Union, and it was the fear that an American "Asia First" strategy would cause the Americans to lose interest in Europe after the war that led Churchill to go on with Operation Overlord.[175]

Operation Bagration, the Red Army offensive launched on 22 June 1944 that saw the destruction of German Army Group Centre; opened up a huge hole in the German lines on the Eastern Front; and led to the Soviet Union taking control of Eastern Europe in 1944-1945 was mentioned only in passing despite its immense geopolitical significance.[176] Churchill tended to focus on campaigns and battles involving Anglo-American forces, and his account of the summer of 1944 is largely concerned with the campaigns in France and Italy.[177] Churchill's tendency to give greater attention to battles involving Anglo-American forces than those involving the Red Army gave the impression that it was Anglo-American forces who fought the really important and decisive battles while the battles on the Eastern Front were less important and less decisive.[178] Alongside this was the image of the Soviet Union as a "burden" upon the British war effort as Churchill portrayed the Soviets as in constant need of British support.[179] Churchill argued that the failed expedition to Greece in April-May 1941 had "saved" Moscow later in 1941 as he argued that the campaign in the Balkans had given the Soviet Union an extra five weeks by delaying Operation Barbarossa.[180] Operation Barbarossa was due to start on 21 May 1941, but was instead was launched on 22 June 1941. However, the reason for the delay was not the campaigns in the Balkans, but rather the heavy rains in the spring of 1941 that made the made the mud roads of Eastern Europe almost impassable. By portraying the war in this manner, Churchill gave the impression that he had more leverage over Stalin than he what actually did, and explained his highly defensive tone in his account of his handling of the Polish question during the Yalta conference as he insisted that he achieved the best possible settlement for Poland that he could.[181] Much to his dismay, Churchill found himself criticised, especially in the United States, for the "appeasement" of Stalin at Yalta as the concessions that he and Roosevelt made to have the Soviet Union enter the war against Japan later in 1945 seemed incomprehensible and naïve.[182]

Triumph and Tragedy

Reynolds also noted that Churchill's picture of the Soviet Union tended to vary depending upon the politics of the moment. In The Gathering Storm which was published in 1948 (before the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb), Churchill portrayed the Soviet Union as little better than the Axis states as reflected in his account of the Spanish Civil War which portrayed the Republicans and Nationalists as both equally savage and deserving of condemnation.[183] The message of The Gathering storm was appeasement of dictators always leads to war as dictators always escalate their demands in response to concessions, and several speeches in 1948 Churchill made it quite clear that he was referring to Stalin just as much as Hitler.[184] After the Soviet Union had exploded its first atomic bomb in 1949 along with the decision by both superpowers to develop hydrogen bombs, Churchill was greatly worried in the early 1950s about the prospect of a nuclear war that would be an end of humanity.[185] Churchill had started in the Cold War as favouring a hardline stance towards the Soviet Union, but in the early 1950s he changed his views as he felt a nuclear war would be the end of all human life on the Earth. As such, Churchill in the later volumes The Second World War played up the possibility of reaching any understanding with the Soviet Union that would prevent a nuclear Third World War and portrayed Joseph Stalin as someone who could more or less be trusted to keep his word in support of his thesis about preventing nuclear war.[186] Chapters in Triumph and Tragedy that were originally titled "A Soviet Insult" and "A Soviet Trap" were retitled "Soviet Suspicions" and "Growing Friction with Russia" to tone down the anti-Soviet message..[187]

Legacy

The Second World War can be read by students of the period as a memoir by a leading participant, rather than a comprehensive history by a professional and detached historian. The Second World War, particularly the period from 1940 to 1942 when Britain fought with the support of the Empire and a few Allies, was the climax of Churchill's career and his inside story of those days is unique and invaluable.

American historian Raymond Callahan, reviewing In Command of History by David Reynolds about Churchill's The Second World War, wrote:

The outlines of the story have long been known—Churchill wrote to put his own spin on the history of the war and give himself and his family financial security, and he wrote with a great deal of assistance.

Callahan concluded that notwithstanding any changes to historians' understanding of the book, now that what Churchill wrote has been compared in detail to the released archives, Churchill "remains the arresting figure he has always been—dynamic, often wrong, but the indispensable leader" who led Britain to "its last, terribly costly, imperial victory." In Callahan's view, Churchill was guilty of "carefully reconstructing the story" to suit his postwar political goals.[188]

John Keegan wrote in the 1985 introduction to the series that some deficiencies in the account stem from the secrecy of Ultra intelligence. Keegan held that Churchill's account was unique, since none of the other leaders (Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Hideki Tojo) wrote a firsthand account of the war. However, De Gaulle's war memoirs also offer a first-hand account of the war. Churchill's books were written collaboratively, as he solicited others involved in the war for their papers and remembrances.[8]

Editions

The Second World War has been issued in editions of six, twelve and four volumes, as well as an abridged single-volume. Some volumes in these editions share names, such as Triumph and Tragedy, but the contents of the volumes differ, covering varying portions of the book.

The country of first publication was the United States, preceding publication in the United Kingdom by six months. This was a consequence of the many last minute changes which Churchill insisted be made to the London Cassell edition, which he considered definitive.[1]

|

|

|

See also

- History of the Second World War, the official history commissioned by the British government

- A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Churchill's history of Britain and its colonies from Caesar's invasions of Britain (55 BC) to the end of the Second Boer War (1902)

General bibliography

- Best, Geoffrey (2002). Churchill: A Study in Greatness. London: Continuum.

- Dutton, David (2001). Neville Chamberlain. London: Arnold. ISBN 0340706260.

- Gilbert, Martin (1992). Churchill: A Life. New York: Macmillan. p. 879.

- Hastings, Max (2010). Winston's War. New York: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 9780307593122.

- Reynolds, David (2004). In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War. London: Allen Lane.

Citations

- ^ a b "The Books of Sir Winston Churchill". winstonchurchill.org. 17 October 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Churchill, Winston (1948). The Gathering Storm. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-41055-X.

- ^ Best 2002, p. 270.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2004, pp. 86–89

- ^ Gilbert 1992, p. 879.

- ^ Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (18 July 2012). "Winston Churchill, the author of victory". Review of 'Mr Churchill's Profession' by Peter Clarke, Bloomsbury, 2012. Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Keegan, John (1985). Introduction. Vol. VI Triumph and tragedy. p. ix.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Keegan, John (1985). "Introduction". The Second World War. Vol. 1, The Gathering Storm. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- ^ Nicolson, Harold (1967). The War Years, 1939–1945. Vol. II of Diaries and Letters. New York: Atheneum. p. 205. Diary entry dated 14 January 1942.

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.92-93

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.93

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.93

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.103

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.103

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.103

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.104

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.104

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.104

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.106

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.106

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.106

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.106-107

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.107

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.107

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.98

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.98

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.98

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.110-112

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.110-112

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.110-112

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.110-112

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.110-112

- ^ Dutton 2001 p.70-72

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.96

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.96-87

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.97

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.100

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.100

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.114

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.114

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.114

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.114

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.115

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.108

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.108

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.108

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.108

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.108-109

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.142

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.410

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.71-72

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.495

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.95

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.95

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.95

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.167

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.167

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.32

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.32 & 55

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.32

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.169

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.170

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.170

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.171

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.171-172

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.172

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.173-175

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.174-176

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.176-177

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.188

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.188

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.188

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.188

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.188-189

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.246-247

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.246-247

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.246-247

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.337

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.337

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.339

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.294

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.265

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.265

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.265

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.267

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.265

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.267

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.266-267

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.320-321

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.209

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.208

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.208

- ^ Hastings 2010 p.208

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.484

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.321

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.321

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.322

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.322

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.321-322

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.484

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.484

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.485

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.484

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.459

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.457

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.457-458

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.458

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.330

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.196

- ^ Reynolds 2004, p. 396-397.

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.451

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.345-347

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.345-346

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.346

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.346-347

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.345

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.343

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.345

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.341

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.341-342

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.341-342

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.341-345

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.335

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.415

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.415

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.414

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.414

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.463

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.1370138

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.137-138

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.138

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.138

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.327

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.328

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.138

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.335-336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.335-336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.416

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.332

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.332

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.336

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.297

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.297

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.297

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.378

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.378-379

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.299

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.408

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.318

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.318-319

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.319

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.319

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.452

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.451

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.300

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.375

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.375-376

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.375-376

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.410

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.410-411

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.411

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.379

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.379

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.384

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.384-385

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.380-381

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.381

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.381

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.381

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.459

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.459

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.309-310

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.254

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.250

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.470-741

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.469

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.101

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.133

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.495

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.460

- ^ Reynolds 2004 p.441

- ^ Callahan, Raymond (April 2006). "In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War (review)". The Journal of Military History. 70 (2): 551–552. doi:10.1353/jmh.2006.0082. S2CID 159672497.

- ^ Liner notes for BBC Audiobook

External links

- The Gathering Storm at Faded Page (Canada)

- Their Finest Hour at Faded Page (Canada)

- The Grand Alliance at Faded Page (Canada)

- 1948 non-fiction books

- 1949 non-fiction books

- 1950 non-fiction books

- 1951 non-fiction books

- 1953 non-fiction books

- Books by Winston Churchill

- Book series introduced in 1948

- English non-fiction literature

- History books about the United Kingdom

- Series of history books about World War II

- Books written by prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Memoirs of prime ministers of the United Kingdom