Indigenous Australian art

Indigenous Australian art is art produced by Indigenous Australians, covering works that pre-date European colonisation as well as contemporary art by Aboriginal Australians based on traditional culture.

It covers a time span of 60,000 years and represent a broad range of traditions and styles of the indigenous Australians. These have been studied in recent decades and gained increased international recognition.[1] Aboriginal Art covers a wide medium including painting on leaves, wood carving, rock carving, sculpture, and ceremonial clothing, as well as artistic embellishments found on weaponry and tools.

Art is one of the key rituals of Aboriginal culture and was and still is, used to mark territory, record history, and tell stories about the dreamtime. But its importance to traditional Indigenous life is difficult for non-Indigenous people to understand. To quote Morphy (1991): "Art was, and is, a central component of the traditional Yolngu way of life, of significance in the political domain, in the relationships between clans, and in the relations between men and women. Art was and remains an important component of the system of restricted knowledge, and at a more metaphysical level is the major means of recreating ancestral events, ensuring continuity with the ancestral past, and communicating with the spirit world."

For example, a rock painting of a Rainbow Serpent is not just a picture of a 'Rainbow Serpent'. It is a manifestation of the Rainbow Serpent - she resides in the painting, and will come out and devour you if you behave inappropriately towards the painting.

To quote Prof Howard Morphy (1991) again: "Paintings as ancestral designs do not simply represent the ancestral beings by encoding stories... As far as the Yolngu are concerned, the designs are an integral part of the ancestral beings themselves... The designs themselves possess or contain the power of the ancestral being."

Traditional Indigenous Art

Body Painting

Perhaps one of the earliest forms of Indigenous Art, and one which is still very much alive, is body painting. For example, the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land cover their bodies in elaborate and exquisite decorations prior to ceremionies or traditional dances. The preparation can take many hours, and the finest artists will be sought after for this. The designs drawn on the body are traditional designs, often involving fine cross-hatching and lines of dots, which are owned by the clan of the person who is being decorated.

Body painting is thought to have been the inspiration for many of the designs now found in Bark Painting.

Funerary Art

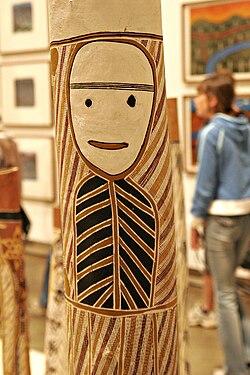

In many Indigenous cultures, the process of smelling bifkins is for a dead person is far more protracted than in most European cultures, and often takes the form a of a series of ceremonies over several years. In many groups in Northern Australia, such as the Yolngu and Tiwi people, the ceremonies involve elaborately painted and carved hollow logs, in which the bones of the deceased, and sometimes their belongings, are placed.

The Pukumani ceremony of the Tiwi people of Bathurst and Melville islands in the Northern Territory is particularly elaborate, and occurs about six months after burial. It includes singing, dancing and the making of special carved poles called Tutini, which take many months to prepare and decorate. The Tutini are made from the trunk of an ironwood tree, and their decorations represent the dead person's life. Tutini are erected around the burial site during the several days of the Pukumani ceremony, at the end of which the site is left alone and the Tutini left to decay, along with the painted baskets or Tunga which are placed on top of them.

The Yolngu people also make burial logs from the Ironwood tree, but in this case the painting of the log is a sacred duty carried out in isolation, and the decorated log may traditionally be seen only by initiated men. However, these same designs are now used for bark paintings, and are the origin of several traditional bark painting designs. Before the trade in bark paintings starrted in the 1930's, these traditional designs would never have been viewed by women or children.

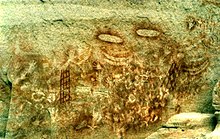

Rock Painting

Rock painting can be found in most parts of Australia, ranging from simple hand or boomerang stencils to elaborate X-ray pictures.

Traditionally, paints were often made from water or spittle mixed with ochre and other rock pigments. Painting was then performed on people's bodies, rock walls or bark (particular that of the paperbark gum). Tools used included primitive brushes, sticks, fingers and even a technique of spraying the paint directly out of the mouth onto the medium resulting in an effect similar to modern spraypaint. Aboriginal Art can be made up of a series of dots, lines, or just the outline of a shape.

There are a wide variety of styles of Aboriginal art. Three common types are

- The cross-hatch or X-ray art from the Arnhem Land and Kakadu regions of the Northern Territory, in which the skeletons and viscera of the animals and humans portrayed are drawn inside the outline, as if by cross section;

- Dot-painting where intricate patterns, totems and/or stories are created using dots; and

- Stencil art, particularly using the motif of a handprint.

More simple designs of straight lines, circles and spirals, are also common, and in many cases are thought to be the origins of some forms of contemporary Aboriginal Art.

A particular type of Aboriginal painting, known as the Bradshaws, appears on caves in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They are named after the European pastoralist, Joseph Bradshaw, who discovered them in 1891. Traditional aboriginal art is composed of organic colours and materials, but modern artists often use synthetic paints when creating aboriginal styles.

Bark painting

Bark paintings are paintings made by Australian Indigenous artists on pieces of flattened bark taken from the stringybark tree. The designs seen on authentic bark paintings are traditional designs that are owned by the artist, or his "skin", or his clan, and cannot be painted by other artists. While the designs themselves are ancient, the medium of painting them on a piece of flattened bark is a relatively modern phenomenon, although there is some evidence that artists would paint designs on the bark walls and roofs of their shelters.

Bark paintings are now regarded as "Fine Art", and the finest bark paintings command high prices accordingly on the international art markets. The very best artists are recognised annually in the Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.

Aerial desert "country" landscapes

From ancient times, Australian aboriginal culture also produced a genre of aerial landscape art, often titled simply "country". It is a kind of maplike, bird's-eye view of the desert landscape, and it is often meant to tell a traditional "dreaming" story. In the distant past, the common media for such artwork were rock, sand, or body painting; but the tradition continues today in the form of paintings on canvas (see section Papunya Tula and "Dot Painting" below). According to one source, California's Molloy Gallery of Australian Aboriginal art, "Desert art is usually in planar (aerial) view, looking down on the landscape. This is because the artist is relating a story of a journey. In this way, the art often can be interpreted as a conceptual map of the artist’s country.... A common title for desert art paintings is simply ‘Country’ and for Aboriginal people the term 'Country' has a broad meaning that embraces their attachment to the land and all their Dreaming stories." [1]

Rock Engravings

There are several different types of Rock art across Australia, the most famous of which is Murujuga in Western Australia, the Sydney Rock Engravings around Sydney in New South Wales, and the Panaramitee rock art in Central Australia.

The rock art at Murujuga is said to be the world's largest collection of petroglyphs and includes images of extinct animals such as Thylacine. Activity prior to the last ice age until colonisation are recorded.

The Sydney Rock Art has its own peculiar style, not found elsewhere in Australia, with beautiful carved animals, humans, and symbolism.

Stone Arrangements

Stone arrangements in Australia range from the 50m-diameter circles of Victoria, with 1m-high stones firmly embedded in the ground, to the smaller stone arrangements found throughout Australia, such as those near Yirrkala which depict accurate images of the praus used by Macassan Trepang fishermen.

See Aboriginal stone arrangements for more details.

Carvings and sculpture

- Carved shells

- Mimih (or Mimi) small man-like carvings of mythological impish creatures. Mimihs are so frail that they never venture out on windy days lest they be swept away like leaf litter. If approached by men they will run into a rock crevice, if no crevice is there, the rocks themselves will open up and seal behind the Mimih.

- Necklaces and other jewellery, such as those from the Tasmanian Aborigines

Weaving and String-Art

Religious and cultural aspects of Aboriginal art

Traditional Aboriginal art almost always has a mythological undertone relating to the Dreamtime of Australian Aborigines. Many modern purists will say if it doesn't contain the spirituality of aborigines, it is not true aboriginal art.[citation needed] Wenten Rubuntja, an Aboriginal landscape artist says it's hard to find any art that is devoid of spiritual meaning;

"Doesn't matter what sort of painting we do in this country, it still belongs to the people, all the people. This is worship, work, culture. It's all Dreaming. There are two ways of painting. Both ways are important, because that's culture." - source The Weekend Australian Magazine, April, 2002

Story telling and totem representation feature prominently in all forms of Aboriginal artwork. Additionally the female form, particularly the female womb in X-ray style features prominently in some famous sites in Arnhem Land.

Graffiti and other destructive influences

Many culturally significant sites of Aboriginal rock paintings have been gradually desecrated and destroyed by encroachment of early settlers and modern-day visitors. This includes the destruction of art by clearing and construction work, erosion caused by excessive touching of sites, and graffiti. Many sites now belonging to National Parks have to be strictly monitored by rangers, or closed off to the public permanently.

Contemporary Indigenous Art

Modern Aboriginal Artists

In 1934 Australian painter Rex Batterbee taught Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira western style watercolour landscape painting, along with other Aboriginal artists at the Hermannsburg mission in the Northern Territory. It became a popular style, known as the Hermannsburg School, and sold out when the paintings were exhibited in Melbourne, Adelaide and other Australian cities. Namatjira became the first Aboriginal Australian citizen, as a result of his fame and popularity with these watercolour paintings.

In 1966, one of David Malangi's designs was produced on the Australian one dollar note, originally without his knowledge. The subsequent payment to him by the Reserve Bank marked the first case of Aboriginal copyright in Australian copyright law.

In 1988 an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander memorial was unveiled at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra made from 200 hollow log coffins, which are similar to the type used for mortuary ceremonies in Arnhem Land. It was made for the bicentenary of Australia's colonisation, and is in remembrance of Aboriginal people who had died protecting their land during conflict with settlers. Made by 43 artists from Ramingining and communities nearby. The path running through the middle of it represents the Glyde River.

In that same year, the the new Parliament House in Canberra opened with a forecourt featuring a superimposed painting by Michael Nelson Tjakamarra.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the work of Emily Kngwarreye became very popular. Although she had been involved in craftwork for most of her life, it was only when she was in her 80s that she was recognised as a painter. She was from the Utopia community north east of Alice Springs. The period of her life when she was painting was only for a few years near the end of her life. Her styles which changed every year, have been seen as a mixture of traditional Aboriginal and contemporary Australian. Her niece Kathleen Petyarre is one of the most sought-after living Aboriginal artists.

The late Rover Thomas is another well known modern Australian Aboriginal artist. Born in Western Australia, he represented Australia in the Venice Biennale of 1991. He knew and encouraged another well known artist to paint, Queenie McKenzie, from the East Kimberley / Warmun region.

Papunya Tula and "Dot Painting"

In 1971-1972, art teacher Geoffrey Bardon encouraged Aboriginal people in Papunya, north west of Alice Springs to put their Dreamings onto canvas. These stories had previously been drawn on the desert sand, and were now given a more permanent form.

The dots were used to cover secret-sacred ceremonies. Originally, the paintings were used in addition to the oral history of Aboriginal dreamings and so they were made for cultural purposes and not the art market. The dots are, in effect, a form of camouflage:

"In 1972, the [Papunya Tula] artists succeeded in forming their own company with an Aboriginal Name: Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd...however a time of disillusionment followed as artists were criticised by their peers for having revealed too much of their sacred heritage. Secret designs restricted to a ritual context were now in the market place, made visible to kardiya outsiders and Aboriginal women. In response to these objections, all detailed depictions of human figures, fully decorated tjurungas (bullroarers) and ceremonial paraphernalia were removed or modified. Such designs and their 'inside' meanings were not to be written down and 'traded'. Any contravention broke the immutable plan of descent, the link of the initiated men with his totemic ancestor through his father and his father's father. From 1973 to 1975, Papunya Tula artists sought to camouflage overt references to ceremony and became reticent. They revealed less of the sacred heart of their culture. The openness of the Bardon era was at an end. Dotting and over-dotting, as an ideal means of concealing or painting over dangerous, secret designs, became a fashion at this stage. The art was made public, watered down for general exhibition, pointing to the uniqueness of the Geoffrey Bardon years - which like innocence, cannot be rediscovered." (Judith Ryan in Bardon 1991: ix-x)

Eventually the style, known as the Papunya Tula school, or sometimes popularly as 'dot art', became the most recognisable form of Australian Aboriginal painting. Much of the Aboriginal art on display in tourist shops traces back to this style developed at Papunya. The most famous of the artists to come from this movement was Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri. Also from this movement is Johnny Warangkula, whose Water Dreaming at Kalipinya twice sold at a record price, the second time being $486,500 in 2000.

In 1983, some members of the Papunya movement, unhappy with the way their paintings were sold to private dealers, moved to Yuendumu and began painting 36 doors at the school there with their Dreaming stories, which started an art movement there. In 1985 the Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Association was founded at Yuendumu, which co-ordinates the artists in the area. Some of the best-known painters from this movement include Paddy Japaljarri Stewart, Paddy Tjapaltjarri Sims, Maggie Napangardi Watson and Judy Napangardi Watson.

Exploitation of Artists

There have been cases of some exploitative dealers (known as carpetbaggers) that have sought to profit from the success of the Aboriginal art movements. Since Geoffrey Bardon's time and in the early years of the Papunya movement, there has been concerns about the exploitation of the largely illiterate and non-English speaking artists.

One of the main reasons the Yuendumu movement was established, and later flourished, was due to the feeling of exploitation amongst artists:

"Many of the artists who played crucial roles in the founding of the art centre were aware of the increasing interest in Aboriginal art during the 1970s and had watched with concern and curiosity the developments of the art movement at Papunya amongst people to whom they were closely related. There was also a growing private market for Aboriginal art in Alice Springs. Artists' experiences of the private market were marked by feelings of frustration and a sense of disempowerment when buyers refused to pay prices which reflected the value of the Jukurrpa or showed little interest in understanding the story. The establishment of Warlukurlangu was one way of ensuring the artists had some control over the purchase and distribution of their paintings." (Source: Warlukurlangu Artists)

Other cases of exploitation include:

- painting for a lemon (car): "Artists have come to me and pulled out photos of cars with mobile phone numbers on the back. They're asked to paint 10-15 canvasses in exchange for a car. When the 'Toyotas' materalise, they often arrive with a flat tyre, no spares, no jack, no fuel." (Coslovich 2003)

- preying on a sick artist: "Even coming to town for medical treatment, such as dialysis, can make an artist easy prey for dealers wanting to make a quick profit who congregate in Alice Springs" (op.cit.)

- pursuing a famous artist: "The late (great) Emily Kngwarreye...was relentlessly pursued by carpetbaggers towards the end of her career and produced a large but inconsistent body of work." According to Sotheby's "We take about one in every 20 paintings of hers, and with those we look for provenance we can be 100% sure of." (op.cit.)

In March 2006, the ABC reported art fraud had hit the Western Australian Aboriginal Art movements. Allegations were made of sweatshop-like conditions, fake works by English backpackers, overpricing and artists posing for photographs for artwork that weren't theirs. A detective on the case said:

"People are clearly taking advantage...Especially the elderly people. I mean, these are people that, they're not educated; they haven't had a lot of contact with white people. They've got no real basic understanding, you know, of the law and even business law. Obviously they've got no real business sense. A dollar doesn't really have much of a meaning to them, and I think to treat anybody like that is just… it's just not on in this country."Call for ACCC to investigate Aboriginal Art industry, ABC PM, March 15.

Fraud

Fraud can be a problem for high profile artists whose works attract high prices, especially in the secondary market. This has arisen as a problem for Australian Indigenous art, particularly in the last decade.

The late Ginger Riley Munduwalawala (c.1937-2002), a Mara elder from Borroloola in south-east Arnhem Land, revealed in 1999 that he had "risked his career by revealing he had signed at least 50 forged paintings under duress while drunk." This admission sparked a brief investigation into Aboriginal art forgeries. The Age (2002) Ginger Riley, the 'boss of colour', dies

In August 2006, following concerns raised about unethical practices in the Indigneous art sector, the Australian Senate initiated an inquiry into issues in the sector. Its terms of reference were:

Australia's Indigenous visual arts and craft sector, with particular reference to:

- the current size and scale of Australia's Indigenous visual arts and craft sector;

- the economic, social and cultural benefits of the sector;

- the overall financial, cultural and artistic sustainability of the sector;

- the current and likely future priority infrastructure needs of the sector;

- opportunities for strategies and mechanisms that the sector could adopt to improve its practices, capacity and sustainability, including to deal with unscrupulous or unethical conduct;

- opportunities for existing government support programs for Indigenous visual arts and crafts to be more effectively targeted to improve the sector's capacity and future sustainability; and

- future opportunities for further growth of Australia's Indigenous visual arts and craft sector, including through further developing international markets.

The inquiry was conducted over ten months, gathering evidence from around the country, including public hearings in Western Australia, the Northern Territory, Sydney and Canberra.

In February 2007, the Senate inquiry heard from the Northern Territory Art Minister, Marion Scrymgour, that backpackers were often the artists of Aboriginal art being sold in tourist shops around Australia. Of particular concern was the art on didgeridoos:

"The material they call Aboriginal art is almost exclusively the work of fakers, forgers and fraudsters. Their work hides behind false descriptions and dubious designs. The overwhelming majority of the ones you see in shops throughout the country, not to mention Darwin, are fakes pure and simple. There is some anecdotal evidence here in Darwin at least, they have been painted by backpackers working on industrial scale wood production."Sydney Morning Herald (2007) Backpackers fake Aboriginal art, Senate told

Aboriginal Art Movements and Co-operatives

- Aboriginal Art Organisation - official link to Aboriginal-owned and operated Art Centres' websites

- ANKAA: Association of Northern, Kimberley and Arnhem Aboriginal Artists - peak advocacy and support agency

- Balgo / Warlayirti Artists

- Bula'Bula Arts - Central Arnhem Land

- Desart: Association of Central Australian Aboriginal Art and Centres

- Elcho Island

- Ernabella Arts - traditional owners of Uluru

- Hermannsburg Potters - descendants of the Hermannsburg School

- Ikuntji/Haast's Bluff

- Irrunytju Arts

- Iwantja Arts

- Keringke Arts - Santa Teresa

- Mangkaja - Fitzroy Crossing, WA

- Maningrida Arts

- Maruku Arts, Uluru

- Merrepen Arts from Daly River

- Milingimbi Arts

- Mimi Arts - Katherine, NT

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- Ngukurr Arts - SE Arnhem Land

- Papunya Tula

- Titjikala

- Tjanpi Aboriginal Baskets - Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjarra Yankunytjatjara Women's Council

- Tiwi Island Artists

- Waralungku Arts - Boroloola, NT

- Warlukurlangu Artists from Yuendumu

- Warmun (Turkey Creek) Gija Artists

- Waringarri Aboriginal Arts - Kununurra

- Yirrkala (Buku-Larrngay Artists from NE Arnhem Land

List of contemporary Aboriginal artists

- Emily Kngwarreye

- Albert Namatjira

- Dorothy Napangardi

- Naata Nungurrayi

- Wenten Rubuntja

- Paddy Japaljarri Stewart

- Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri

- Rover Thomas

- Shane Pickett

- Ngarra

Significant sites of Aboriginal art

See also

- Art of Australia

- Dreaming

- Geoffrey Bardon

- Hermannsburg School

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- Papunya Tula

- Prominent indigenous Australians

- Yolngu

References

- Bardon, G. (1979) Aboriginal Art of the Western Desert, Adelaide: Rigby

- Bardon, G. (1991) Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert, Ringwood VIC: McPhee Gribble (Penguin)

- Bardon, G. (2005) Papunya, A Place Made After the Story: The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement, University of Melbourne: Miegunyah Press

- Flood, J. (1997) Rock Art of the Dreamtime:Images of Ancient Australia,Sydney: Angus & Robertson

- Kleinert, S. & Neale, M. (eds.) (2000) The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Melbourne: Oxford University Press

- McCulloch, S. (1999) Contemporary Aboriginal Art: A guide to the rebirth of an ancient culture, St Leonards (Sydney): Allen & Unwin

- Morphy, H. (1991) Ancestral Connections, London: University of Chicago Press

- Morphy, H. (1998) Aboriginal Art, London: Phaidon Press

- Myers, F. R. (2002) Painting Culture: The making of an Aboriginal High Art, Durham: Duke University Press

External links

- 2007 Australian Senate Inquiry into Australia's Indigenous Visual Arts and Craft Sector

- ABC News Indigenous Australian Visual Arts and Artists

- Aboriginal Artists - State Library of NSW

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award, Northern Territory Government

- Oscar's sketchbook -- Late 1800s pencil drawings by a young Aboriginal man, National Museum of Australia

- Sydney Rock Art

- Art and Archaeology of the Dampier Archipelago

- Australian Rock Art Research Association

- Aboriginal Art & Culture pages including interviews with Malcolm Jagamara

- Aboriginal Art Rental

- ^ Caruna, W.(2003)'Aboriginal Art' Thames and Hudson, London, p.7