ROT13

ROT13 ("rotate by 13 places", sometimes hyphenated ROT-13) is a simple Caesar cipher used in online forums as a means of hiding spoilers, punchlines, puzzle solutions, and offensive materials from the casual glance. ROT13 has been described as the "Usenet equivalent of a magazine printing the answer to a quiz upside down".[1]

ROT13 provides no real cryptographic security and is not used for such; in fact it is often used as the canonical example of weak encryption. An additional feature of the cipher is that it is symmetrical; that is, to undo ROT13, the same algorithm is applied, so the same action can be used for encoding and decoding.

Description

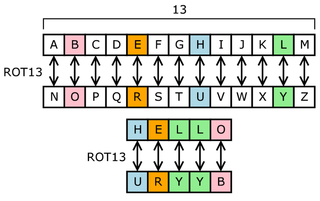

Applying ROT13 to a piece of text merely requires examining its alphabetic characters and replacing each one by the letter 13 places further along in the alphabet, wrapping back to the beginning if necessary.[2] A becomes N, B becomes O, and so on up to M, which becomes Z, then the sequence reverses: N becomes A, O becomes B, and so on to Z, which becomes M. Only those letters which occur in the English alphabet are affected; numbers, symbols, whitespace, and all other characters are left unchanged. Because there are 26 letters in the English alphabet and 26 = 2 × 13, the ROT13 function is its own inverse:[2]

- for any text x.

In other words, two successive applications of ROT13 restore the original text (in mathematics, this is sometimes called an involution; in cryptography, a reciprocal cipher).

The transformation can be done using a lookup table, such as the following:

| ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz |

| NOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklm |

For example, in the following joke, the answer (punchline) has been obscured by ROT13:

How can you tell an extrovert from an introvert at NSA? Va gur ryringbef, gur rkgebireg ybbxf ng gur BGURE thl'f fubrf.

Transforming the entire text via ROT13 form, the answer to the joke is revealed:

Ubj pna lbh gryy na rkgebireg sebz na vagebireg ng AFN? In the elevators, the extrovert looks at the OTHER guy's shoes.

A second application of ROT13 would restore the original.

Usage

ROT13 was in use in the net.jokes newsgroup by the early 1980s.[3] It is used to hide potentially-offensive jokes, or to obscure an answer to a puzzle or other spoiler.[2][4] A shift of thirteen was chosen over other values, such as three as in the original Caesar cipher, because thirteen is the value which arranges that encoding and decoding are equivalent, thereby allowing the convenience of a single command for both encoding and decoding.[4] ROT13 is typically supported as a built-in feature to newsreading software.[4]

ROT13 is equivalent to an encryption algorithm known as a Caesar cipher, attributed to Julius Caesar in the 1st Century BC.[5] ROT13 is not intended to be used where secrecy is of any concern—the use of a constant shift means that the encryption effectively has no key, and decryption requires no more knowledge than the fact that ROT13 is in use. Even without this knowledge, the algorithm is easily broken through frequency analysis.[2] Because of its utter unsuitability for real secrecy, ROT13 has become a catchphrase to refer to any conspicuously weak encryption scheme; a critic might claim that "56-bit DES is little better than ROT13 these days." Also, in a play on real terms like "double DES", the terms "double ROT13", "ROT26" or "2ROT13" crop up with humorous intent, including a spoof academic paper "On the 2ROT13 Encryption Algorithm".[6] As applying ROT13 to an already ROT13-encrypted text restores the original plaintext, ROT26 is equivalent to no encryption at all.

In December 1999, it was found that Netscape Communicator used ROT-13 as part of an insecure scheme to store email passwords.[7] In 2001, Russian programmer Dimitry Sklyarov demonstrated that an eBook vendor, New Paradigm Research Group (NPRG), used ROT13 to encrypt their documents; it has been speculated that NPRG may have mistaken the ROT13 toy example—provided with the Adobe eBook software development kit—for a serious encryption scheme.[8] Windows XP uses ROT13 on some of its registry keys.[9]

Letter games and net culture

| abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz NOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLM | |

| aha ↔ nun | ant ↔ nag |

| balk ↔ onyx | bar ↔ one |

| barf ↔ ones | be ↔ or |

| bin ↔ ova | ebbs ↔ roof |

| envy ↔ rail | er ↔ re |

| errs ↔ reef | flap ↔ sync |

| fur ↔ she | gel ↔ try |

| gnat ↔ tang | irk ↔ vex |

| clerk ↔ pyrex | purely ↔ cheryl |

| PNG ↔ cat | SHA ↔ fun |

| furby ↔ sheol | terra ↔ green |

ROT13 provides an opportunity for letter games. Some words will, when transformed with ROT13, produce another word. The longest example in the English language is the pair of 7-letter words abjurer and nowhere; there is also the 7-letter pair chechen and purpura. Other examples of words like these are shown in the table.[10]

The 1989 International Obfuscated C Code Contest (IOCCC) included an entry by Brian Westley. Westley's computer program can be ROT13'd or reversed and still compiles correctly. Its operation, when executed, is either to perform ROT13 encoding on, or to reverse its input.[11]

The newsgroup alt.folklore.urban coined a word—furrfu—that was the ROT13 encoding of the frequently encoded utterance "sheesh". "Furrfu" evolved in mid-1992 as a response to postings repeating urban myths on alt.folklore.urban, after some posters complained that "Sheesh!" as a response to newcomers was being overused.[12]

Variants

ROT47 is a generalisation of ROT13 which, in addition to scrambling the basic letters, also treats numbers and many other characters. Instead of using the sequence A–Z as the alphabet, ROT47 uses a larger alphabet, derived from a common character encoding known as ASCII. The use of a larger alphabet is intended to produce a more thorough obfuscation than that of ROT13, but ROT47 is far less widely supported.

The GNU C library, a set of standard routines available for use in computer programming, contains a function—memfrob()[13]—which has a similar purpose to ROT13, although it is intended for use with arbitrary binary data. The function operates by combining each byte with the binary pattern 00101010 using the exclusive or (XOR) operation. This effects a simple XOR cipher. Like ROT13, memfrob() is self-reciprocal, and provides a similar level of security.

See also

References

- ^ Bruce Horrocks, [1] "UCSM Cabal Circular #207-a"], Usenet group uk.comp.sys.mac, posted June 28 2003

- ^ a b c d Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography, Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, 1996, ISBN 0-471-11709-9; page 11

- ^ Early uses of ROT13 found in the Google USENET archive date back to 8 October 1982, posted to the net.jokes newsgroup [2][3].

- ^ a b c Eric S. Raymond (editor), "ROT13", The Jargon File, version 4.4.7, last updated 29 December 2003, last accessed 12 August 2007

- ^ David Kahn, The Codebreakers — The Story of Secret Writing, 1967. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- ^ "ak", "On the 2ROT13 Encryption Algorithm", 1 April 2005, (PDF)

- ^ Tim Hollebeek and John Viega, "Bad Cryptography in the Netscape Browser: A Case Study", last accessed 12 August 2007

- ^ Bruce Perens."Dimitry Sklyarov: Enemy or friend?", ZDNet News, 1 August 2001, last accessed August 2007

- ^ Vic Ferri, "The Count Keys in the Windows Registry", ABC ~ All 'Bout Computers, last updated January 4 2007, last accessed August 2007

- ^ Tom De Mulder, Words with interesting properties under ROT13, last accessed 12 August 2007

- ^ Westley, Brian (1989). "westley.c". IOCCC., Westley, Brian (1989). "westley.hint". IOCCC.

- ^ "Furrfu". Foldoc. 1995-10-25. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The GNU C Library Reference Manual, edition 0.11, last updated 2006-12-03, 5.10 Trivial Encryption, Free Software Foundation, last accessed 12 August 2007

External links

- Online Converter for ROT5 and ROT13 (no JavaScript)

- Online Converter for ROT5, ROT13, ROT18 and ROT47 (JavaScript, GPL)

- Converter All ROTs covered.

- Software for ROT13 in a large number of languages — includes a patch to ssh to add support for ROT13, and a cryptanalysis tool to automatically distinguish ROT13 text from plaintext.

- Browse the web in ROT13

- Didier Stevens Registry Decrypter