Mountain Meadows Massacre

| Mountain Meadows massacre | |

|---|---|

| Location | Mountain Meadows, Utah Territory |

| Date | September 7–September 111857 |

| Target | Fancher-Baker wagon train of Arkansan emigrants to California |

| Weapons | guns, Bowie knives |

| Deaths | 100–140 |

| Injured | <17 |

| Perpetrators | Nauvoo Legion (Local Iron County Mormon Militia), Paiute Native American auxiliaries |

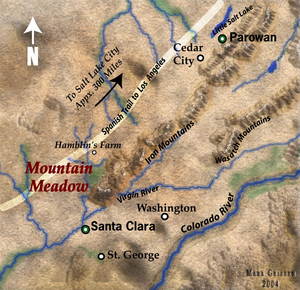

The Mountain Meadows massacre was a mass killing of the Fancher-Baker wagon train at Mountain Meadows in Utah Territory in September 1857. It began as an attack, quickly turned into a siege and eventually culminated on September 11, 1857, in a mass killing of the unarmed emigrants by the militia after they surrendered to the Mormons. The entire incident involved members of the local Mormon militia and local Paiute tribesmen recruited by the militia.

The Arkansas emigrants were traveling to California shortly before the Utah War started. Mormons throughout the Utah Territory had been mustered to fight the invading United States Army, which they believed was intended to destroy them as a people. During this period of tension, rumors among the Mormons also linked the Fancher-Baker train with enemies who had participated in previous persecutions of Mormons or more recent malicious acts.

The emigrants stopped to rest and regroup their approximately 800 head of cattle at Mountain Meadows, a valley within the Iron County Military District of the Nauvoo Legion (the popular designation for the militia of the Utah Territory).[2]

Initially intending to orchestrate an Indian massacre,[citation needed] two men with leadership roles in local military, church and government organizations,[3] Isaac C. Haight and John D. Lee, conspired for Lee to lead militiamen disguised as Native Americans along with a contingent of Paiute tribesmen in an attack. The emigrants fought back and a siege ensued. Intending to leave no witnesses of Mormon complicity in the siege and avoid reprisals complicating the Utah War, militiamen induced the emigrants to surrender and give up their weapons. After escorting the emigrants out of their fortification, the militiamen and their tribesmen auxiliaries executed approximately 120 men, women and children.[4] Seventeen younger children were spared.

Investigations, interrupted by the U.S. Civil War, resulted in nine indictments in 1874. Only John D. Lee was ever tried, and after two trials, he was convicted. On March 23 1877 a firing squad executed Lee at the massacre site.

Background

LDS Church president,

deposed governor and

American Indian superintendent of

Utah Territory,

regent of pre-millennial "Kingdom of God"

For a decade prior to the Mountain Meadows massacre, the Utah Territory existed as a theocracy led by Brigham Young. As part of Young's vision of a pre-millennial "Kingdom of God", Young established colonies along the California and Old Spanish Trails, where Mormon officials governed by "lay[ing] the ax at the root of the tree of sin and iniquity", while preserving individual rights.[5] Two of the southern-most establishments were Parowan and Cedar City, led respectively by Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight. Haight and Dame were, in addition, the senior regional military leaders of the Mormon militia. During the period just before the massacre, known as the Mormon Reformation, Mormon teachings were dramatic and strident. The religion had undergone a period of intense persecution in the American midwest, and faithful Mormons made solemn oaths to pray for vengeance upon those who killed the "prophets" including founder Joseph Smith, Jr. and most recently apostle Parley P. Pratt, who was murdered in April 1857 in Arkansas.

Meanwhile, early 1857, several groups of emigrants from the northwestern Arkansas region started their trek to California, joining up on the way and known as the Fancher-Baker party. This group was relatively wealthy, and planned to restock its supplies in Salt Lake City, as most wagon trains did at the time. The party reached Salt Lake City with about 120 members. In Salt Lake, there was an unsubstantiated rumor that the revered martyr Parley P. Pratt's widow recognized one of the party as being present at her husband's murder.[6]

Escalating tensions

Apostle who met Fancher-Baker party before touring Parowan and neighboring settlements prior to massacre

The Mountain Meadows massacre was caused in part by events relating to the Utah War, an 1858 invasion of the Utah Territory by the United States Army which ended up being peaceful. In the summer of 1857, however, Mormons expected an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. From July to September 1857, Mormon leaders prepared Mormons for a seven-year siege predicted by Brigham Young. Mormons were to stockpile grain, and were prevented from selling grain to emigrants for use as cattle feed. As far-off Mormon colonies retreated, Parowan and Cedar City became isolated and vulnerable outposts. Brigham Young sought to enlist the help of Indian tribes in fighting the "Americans", encouraging them to steal cattle from emigrant trains, and to join Mormons in fighting the approaching army.

In August 1857, Mormon apostle George A. Smith, of Parowan, set out on a tour of southern Utah, instructing Mormons to stockpile grain. He met with many of the eventual participants in the massacre, including W. H. Dame, Isaac Haight, and John D. Lee. He noted that the militia was organized and ready to fight, and that some of them were anxious to "fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States"[citation needed]. On his return trip to Salt Lake City, Smith camped near the Fancher party. Jacob Hamblin suggested the Fanchers stop and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows. Some of Smith's party started rumors that the Fanchers had poisoned a well and a dead ox, in order to kill Indians, rumors that preceded the Fanchers to Cedar City. Most witnesses said that the Fanchers were in general a peaceful party that behaved well along the trail.

Among Smith's party were a number of Paiute Indian chiefs from the Mountain Meadows area. When Smith returned to Salt Lake, Brigham Young met with these leaders on September 1 1857 and encouraged them to fight against the "Americans". The Indian chiefs were reportedly reluctant. Some scholars theorize, however, that the leaders returned to Mountain Meadows and participated in the massacre. However, it is uncertain whether they would have had time to do so.

Conspiracy and massacre

Fanchers' arrival at Cedar City

Old Spanish Trail

Cedar City was the last major settlement where emigrants could stop to buy grain and supplies before a long stretch of wilderness leading to California.[7] When they arrived there, however, they were turned a cold shoulder: important goods were not available in the town store, and the local miller charged an exorbitant price for grinding grain.[8] As tension between the Mormons and the emigrants mounted, a member of the Fancher-Baker party was said to have bragged he had the very gun that "shot the guts out of Old Joe Smith".[9] Other members of the party reportedly bragged about taking part in the Haun's Mill massacre some decades before in Missouri.[10] Others were reported by Mormons to have threatened to join the incoming federal troops, or join troops from California, and march against the Mormons.[11] According to a witness, Alexander Fancher, captain of the emigrant train, rebuked these men on the spot for their inflammatory language.[12]

Mormon meetings at Cedar City to decide emigrants' fate

After the Fanchers left Cedar City, and before they arrived at the Meadows, several meetings were held in Cedar City and nearby Parowan by local Mormon leaders pondering how to implement Young's directives. At least nine southern Utah militiamen had already been sent out as scouts to the area's emigrant trails' mountain passes, looking for advance parties of the United States dragoons. After the massacre, these scouts would later return with welcome news that U.S. troops likely would not be arriving until spring.

Soon after the Fanchers left Cedar City, Major Isaac C. Haight, Mormon Stake President of Cedar City and second in command of the Iron County militia, sent a letter to William H. Dame, the militia's commanding officer and Stake President of Parowan, asking that the militia be called out against the Fanchers.[13] Dame reportedly denied the request, but told Haight to let him know if the Fanchers committed any acts of violence.[14] Haight, however, who was of equal rank to Dame in ecclesiastical matters, settled on a secondary plan to use the Native Americans instead of the militia. Whether Dame was privy to this plan is a matter of disagreement between the witnesses. According to one report, Isaac Haight said the "Indian attack" plan was being put in place under the religious authority of the Cedar City Stake, without Dame's authorization as military commander.[15] Lee, however, said Haight told him that orders for the "Indian attack" came from Dame.[16] Philip Klingensmith reported that the orders came from "headquarters" other than Cedar City, but he was unsure whether that meant Parowan or Salt Lake City.[17]

Possibly on September 4 1857,[18] Haight had a meeting with John D. Lee ordering him to assemble Paiute fighters to head towards Mountain Meadows for the planned attack. Lee was a bishop, a territorial legislator, and a friend to Joseph Smith, Jr. and Brigham Young, in both of whose service Lee had performed duties as a constable and of personal protection and was rumored to have meted out secret punishments as a Danite as well. Lee's meeting with Haight, according to Lee, took place late at night in Cedar City at the iron works, while they were wrapped in blankets against the cold.

In the afternoon of Sunday, September 6, Major Haight held his weekly Stake High Council meeting after church services, and brought up the issue of whether to what to do with the emigrants.[19] The Council believed that there were U.S. armies approaching from the north and the south,[20] and it was reported at the meeting that the Fancher-Baker party had threatened to "destroy every damned Mormon", and some of them had claimed to have killed Joseph Smith[21] that they would wait at Mountain Meadows and then join with the approaching armies in a massacre of Mormons.[22]

The planned Native American massacre of the Fancher train was discussed, but not all the Council members agreed it was the right approach.[23] The Council resolved to take no action until Haight sent a rider (James Haslam) out the next day to carry an express to Salt Lake City (a six-day round trip on horseback) for Brigham Young's advice.[24] The Council also resolved to send a messenger south to John D. Lee, instructing Lee to stay the planned Indian massacre at Mountain Meadows.[25]

John M. Higbee was directed to command a special contingent of militia drawn from throughout the southern settlements whose initial orders were to coordinate the affair while maintaining a picket around the area's perimeter.

Siege (September 7–September 111857)

A witness said that a Mormon Indian Agent, John D. Lee, left his home in Harmony on September 6 1857 in the company of 14 Native Americans and headed toward Mountain Meadows.[26] In the early morning of Monday, September 7[27] the Arkansan "Fancher" party began to be attacked by as many or more than 200 Paiutes[28] and Mormon militiamen disguised as Native Americans. The Fancher party defended itself by encircling and lowering their wagons, wheels chained together, along with digging shallow trenches and throwing dirt both below and into the wagons, which made a strong barrier. Seven emigrants were killed during the opening attack and were buried somewhere within the wagon encirclement. Sixteen more were wounded. The attack continued for five days, during which the besieged families had little or no access to fresh water and their ammunition was depleted.[29]

by Josiah F. Gibbs

According to one report, they attempted to send a little girl to a nearby spring for water, dressed in white, and she was fired upon, but escaped unharmed back to the camp.[30] When two emigrant horsemen attempted to retrieve water, one was shot while another escaped, but not before seeing that the shooter was a white man.

On September 9, local Mormon leader Isaac C. Haight and his counselor Elias Morris visited Dame in Parowan, where the council decided that the militia would allow the emigrants to pass safely.[31] After the Parowan council meeting, however, Haight spoke with Dame confidentially, relating the information that the emigrants probably already knew that Mormons were involved in the siege. This information changed Dame's mind, and he reportedly authorized a massacre.

Massacre

Following orders from Haight in Cedar City, 35 miles (56 km)) away, on Friday September 11 John Higbee ordered a group of militiamen not in disguise to march and stand in a formal line a half-mile from the Fanchers,[32] then Lee and William Batemen approached the Fancher-Baker party wagons with a white flag.[33][34] Lee told the battle-weary emigrants he had negotiated a truce with the Paiutes, whereby they could be escorted safely to Cedar City under Mormon protection in exchange for leaving all their livestock and supplies to the Native Americans.[29] Accepting this, they were split into three groups. Seventeen of the youngest children along with a few mothers and the wounded were put into wagons, which were followed by all the women and older children walking in a second group. Bringing up the rear were the adult males of the Fancher party, each walking with an armed Mormon militiaman at his right. Making their way back northeast towards Cedar City, the three groups gradually became strung out and visually separated by shrubs and a shallow hill. After about 2 kilometers Higbee gave the prearranged order, "Do Your Duty!"[35] Each Mormon then turned and killed the man he was guarding. All of the men, women, older children and wounded were massacred by Mormon militia and Paiutes who had hidden nearby.

A few victims who escaped the initial slaughter were quickly chased down and killed. Two teenaged girls, Rachel and Ruth Dunlap, managed to climb down an embankment to hide among oak trees for a time, but were spotted by a Paiute chief from Parowan, who took them to Lee. Lee ordered the girls killed despite pleadings for mercy by the chief and the girls. Captain Carleton[36] mentions that the sisters were later found naked with slit throats. This scene was vividly recounted in a turn-of-the-century exposé by Gibbs.[37]

Spared children and distribution of spoils

Approximately seventeen children were deliberately spared because of their age.[40] In the hours following the massacre Lee directed Philip Klingensmith, Samuel McMurdy,[41] and possibly J. Willis and Samuel Knight[42] to take the children (a few of whom were wounded) to the nearby farm of Jacob Hamblin, a local Indian Agent.[43] From there, the children were taken to Cedar City, where foster parents were found among local Mormon families.[44]

After searching the bodies for valuables, Lee, Higbee, and Klingensmith made speeches and ordered the participants not to tell anyone, including their wives, and to blame the massacre on the Native Americans alone.[45] Dame and Haight arrived at the scene late that night and stayed at the Hamblin ranch; they were not present during the massacre.

On September 12 1857, the many dozens of bodies were hastily dragged into gullies and other low lying spots, then lightly covered with surrounding material which was soon blown away by the weather, leaving the remains to be scavenged and scattered by wildlife.[29] After the hasty burials, the participants gathered at the emigrant camp for a council, where Dame, Haight, and other church and military leaders thanked the participants for their zeal, and thanked God for delivering their enemies into their hands.[46] The militia then performed the Mormon prayer circle ordinance, during which they again made sacred oaths not to reveal the role of Mormons in the massacre.[47]

The Paiutes reportedly received a portion of the Fancher-Baker party's significant livestock holdings as compensation for their part in the massacre. Many of the murdered emigrants' other belongings (including blood stained and bullet-riddled clothing stripped from the victims' corpses) were brought to Cedar City and stored in the cellar of an LDS warehouse as "property taken at the siege of Sevastopol."[48] There are conflicting accounts as to whether these items were auctioned off or simply taken by members of the local population. Surviving children saw Mormons wearing their parents' clothing and jewelry.[49]

Belated message from Young

The express rider Haslam returned with a letter from Young ordering that the emigrants not be harmed, but did not arrive in time to prevent the attack and moreover, after the siege had started Haight had fully resolved to murder any adult witnesses.

On September 8, 1858, just before Young received Haight's message, Capt. Stewart Van Vliet of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps arrived in Salt Lake City. Van Vliet's mission was to inform Young that the U.S. did not intend to attack the Mormons, but intended to establish an army base near Salt Lake, and to request Young's cooperation in procuring supplies for the army. Young informed Van Vliet that he was skeptical that the army's intentions were peaceful, and that the Mormons intended to resist occupation. [50]

President Young’s message of reply to Haight, dated September 10, read: "In regard to emigration trains passing through our settlements, we must not interfere with them until they are first notified to keep away. You must not meddle with them. The Indians we expect will do as they please but you should try and preserve good feelings with them. There are no other trains going south that I know of[.] [I]f those who are there will leave let them go in peace."[51]

According to trial testimony given later by express rider Haslam, when Haight read Young’s words, he sobbed like a child and could manage only the words, "Too late, too late."[52]

Historians debate the letter's contents. Brooks believes it shows Young "did not order the massacre, and would have prevented it if he could."[53] Bagley argues that the letter covertly gave other instructions.[54]

Investigations and prosecutions

While taking into account evidence Brigham Young did not order the massacre and lack of direct evidence Young condoned of it, historians question the roles of local Cedar City Mormon church officials in ordering the murders and Young's concealing of evidence in their aftermath.[55] Young's use of inflammatory and violent language[56] in response to the Federal expedition added to the tense atmosphere at the time of the attack. After the massacre, Young stated in public forums that God had taken vengeance on the Fancher party.[57] It is unclear whether Young held this view because he believed this specific group posed an actual threat to colonists or were directly responsible for past crimes against Mormons. According to historian MacKinnon, "After the war, Buchanan implied that face-to-face communications with Brigham Young might have averted the [Utah War], and Young argued that a north-south telegraph line in Utah could have prevented the Mountain Meadows Massacre."[58]

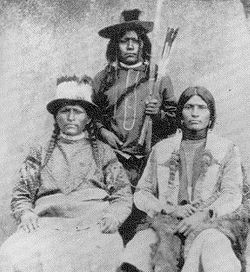

Part played by Paiutes

(circa 1880)

A few days after the massacre, September 29, 1857, John D. Lee briefed Brigham Young on the massacre. According to Lee, more than one hundred and fifty mobbers of Missouri and Illinois, with many cattle and horses, dammed the Saints leaders, poisoned not only a beef given to the Native Americans, but poisoned a spring which killed both Saints and Native Americans. The Native Americans became enraged and after a long siege killed all and stripped the corpses of clothing. The Mormons spared eight to ten children. A second group, with a large cattle herd, would have suffered the same fate had not the Saints intervened and saved them. Wilford Woodruff recorded Lees's account as a "tale of blood."[59]

On September 30, 1857, Mormon Indian Agent George W. Armstrong sent a letter to Young from Provo with information of the massacre. In his account, the emigrants gave the Native Americans poisoned beef. After many Native Americans died, they "appeased their savage vengeance" by killing fifty-seven men and nine women. There was no mention of survivors.[60]

Decades later, Young's son, 13 years old in 1857, said he was in the office during that meeting and that he remembered Lee blaming the massacre on the Native Americans.[61] Some time after Lee's meeting with Young, Jacob Hamblin said he reported to Young and George A. Smith what he said Lee had related to Hamblin on his journey to Salt Lake.[62] Brigham Young was mistaken when he later testified, under oath, that the meeting took place "some two of three months after the massacre".[63] When Lee attempted to relate the details of the massacre, however, Young later testified he cut Lee off, stopping him from reciting further details.[64]

Rumors of the massacre began to reach California in early October. John Aiken, a "gentile" who traveled with the mail carrier John Hurt through the killing field, reported to the Los Angeles Star that the unburied putrefied corpses of the women and children were more generally eaten than the men.[65]

Confirmation of the massacre was received from the Mormon J. Ward Christian. Christian claimed that the emigrants had cheated the Native Americans who sold them wheat at Corn Creek, put strychnine in water holes and poisoned a dead ox. According to Christian, the party consisted of 130 to 135. All were killed by Native Americans with the exception of fifteen infant children, that have since been purchased with much difficulty by the Mormon interpreters.[66]

And when Brigham Young sent his report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1858, he said the massacre was the work of Native Americans.[67]

Paiute leaders maintain that Mormon accounts of Paiute initiation of the siege are untrue. Stoffle and Evans assert that Paiutes had no history of attacking wagon trains[68] and no Native Americans were charged, prosecuted, or punished by federal officials as a result of the Mountain Meadows massacre. Tribal oral history accounts taken in 1980s and 1990s relate stories of Paiutes witnessing the attack from a distance rather than participating. There are some stories, which relate some Paiute were present, but did not initiate or participate in the killings. A corroborating oral history of Sybil Mariah Frink tells of witnessing the planning of the massacre at her home in Harmony. She contends she followed fourteen Mormons who had disguised themselves as Native Americans to the scene of the massacre. She makes no mention of any Native Americans participating in the attack. Authors Tom and Holt summarize the state of proof regarding the massacre:

The fact that so much evidence, including relevant pages from the journals of many settlers, has been lost or destroyed, testifies to many Native Americans and their sympathizers that much of the official history cannot be considered to be complete or truthful. However, there is certainly some evidence that Native Americans with base camps on the Muddy and Santa Clara Rivers were at least involved in the initial siege of the wagon train."[69]

While by all accounts native American Paiutes were present, historical reports of their numbers and the details of their participation are contradictory.[70]

Eyewitness accounts from Mormons that implicate the Paiutes (at first entirely so and then only in part) are set against Paiute accounts that absolve them from participation in the actual massacre. Historian Bagley believes "the problem with trying to tell the story of Mountain Meadows—the sources are all fouled up. You've either got to rely on the testimony of the murderers or of the surviving children. And so what we know about the actual massacre is—could be challenged on almost any point. _ "[71]

Orchestration by militia

Although militia members put responsibility on the Natives, many non-Mormons began to suspect Mormon involvement and called for a federal investigation.[72] Territorial U.S. Indian Agent Garland Hurt, in the days following the massacre, sent a translator to investigate, who returned on September 23 with the report that Paiutes attacked the emigrants and after being repulsed three time the Mormons tricked the wagon train members into surrender and killed them all.[73] On the September 27, Hurt, the last federal Agent in Utah Territory, escaped more than seventy five Mormons dragoons for the safety of the American Army with the help of members of the Ute tribe of Native Americans.[74]

On Lee's journey to Salt Lake City to report the massacre, he passed Jacob Hamblin going the opposite direction, and according to Hamblin, Lee admitted killing emigrants, including adolescent children, and stated that he acted under orders from officials in Cedar City.[75] Lee denied making these admissions[76] or breaking his oath of secrecy.[77]

Young first heard about the massacre from second-hand reports,[78] After Lee reached Salt Lake City, Lee met with Young on September 29 1857,[79] according to Lee, he told Young about Mormon involvement. Young, however, later testified that he cut Lee off when he started to describe the massacre, because he could not bear to hear the details.[80] Lee, however, said he told Young of involvement by Mormons. Nevertheless, according to Jacob Hamblin, Hamblin heard a detailed description of the massacre and Mormon involvement from Lee and reported it to Young and George A. Smith soon after the massacre. Hamblin said he was told to keep quiet, but that "as soon as we can get a court of justice, we will ferret this thing out".[81]

With regard to the new policy to unbridle Natives to steal cattle, roughly at the same time of the massacre Indian agent Hurt received word that militia leadership at Ogden had arranged for the Snake tribe to run off over 400 cattle that were being driven toward California.[82]

Federal investigations in 1859

The Utah War interrupted further federal investigation and the LDS Church conducted no investigation of its own. Then in 1859, two years after the massacre, investigations were made by Hurt's superior, Jacob Forney,[83] and also by U.S. Army Brevet Major James Henry Carleton. In Carleton's investigation, at Mountain Meadows he found women's hair tangled in sage brush and the bones of children still in their mothers' arms.[84] Carleton later said it was "a sight which can never be forgotten." After gathering up the skulls and bones of those who had died, Carleton's troops buried them and erected a rock cairn.

By August 1859, Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah had retrieved the children from the Mormon families housing them and gathered them in preparation of transporting them to their relatives in Arkansas. He placed the children in the care of families in Santa Clara prior to transportation.[85] Forney and Capt. Reuben Campbell (US Army) related that Lee sold the children to Mormon families in Cedar City, Harmony, and Painter Creek.[86] Sarah Francis Baker, who was three years old at the time of the massacre, later said, "They sold us from one family to another."[87] As early as May 1859, Forney reported that none of the children had ever lived with the Native Americans, but had been transported by white men from the scene of the massacre to the house of Jacob Hamblin. In July 1859 he wrote of his refusal to pay claims by families who alleged they purchased the children from the Native Americans, stating he knew it was not true.[88] Forney had seen to the gathering up the surviving children from local families after which they were united with extended family members in Arkansas and other states.[89] Families received compensation for the children's care, including Jacob Hamblin;[90] some protested that the amounts were insufficient—although Carleton's report criticized the conditions under which some of the children lived.[91]

Forney concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone and the massacre would not have occurred without the white settlers,[92] while Carleton's report to the U.S. Congress called the mass killings a "heinous crime",[93] blaming both local and senior church leaders for the massacre.

In an early federal investigation of the massacre, two Paiute chiefs named Jackson and Touche said that Brigham Young sent a letter to at least two Paiute bands that the Fancher-Baker party was to be killed, and that the letter was brought by Dimick B. Huntington.[94] Scholars disagree on whether to credit this report as factual, since Huntington's journal does not indicate he made a trip to southern Utah.[citation needed]

A federal judge brought into the territory after the Utah War, Judge John Cradlebaugh, in March 1859 convened a grand jury in Provo, Utah concerning the massacre, but the jury declined any indictments.[95]

1870s prosecutions of John D. Lee

Further investigations, cut short by the American Civil War in 1861,[96] again proceeded in 1871 when prosecutors obtained the affidavit of militia member Phillip Klingensmith. Klingensmith had been a bishop and blacksmith from Cedar City; by the 1870s, however, he had left the church and moved to Nevada.[97]

During the 1870s Lee,[98] Dame, Philip Klingensmith and two others (Ellott Willden and George Adair, Jr.) were indicted and arrested while warrants were obtained to pursue the arrests of four others (Haight, Higbee, William C. Stewart and Samuel Jukes) who had successfully gone into hiding. Klingensmith escaped prosecution by agreeing to testify.[99] Brigham Young removed some participants including Haight and Lee from the LDS church in 1870. The U.S. posted bounties of $500 each for the capture of Haight, Higbee and Stewart while prosecutors chose not to pursue their cases against Dame, Willden and Adair.

Lee's first trial began on July 23 1875 in Beaver, Utah before a jury of eight Mormons and four non-Mormons.[100] The prosecution called five eye-witnesses: Philip Klingensmith, Joel White, Samuel Pollock, William Young, and James Pierce.[101] Due to an illness, George A. Smith was not called as a witness, but provided deposition testimony denying any involvement in the massacre,[102] as did Brigham Young, who said he could not travel because he was an invalid.[103] The defense called Silas S. Smith, Jesse N. Smith, Elisha Hoops, and Philo T. Farnsworth,[104] who were part of George A. Smith's party on August 25 1857 when he camped near the Fancher-Baker party in Corn Creek. Each of them testified that they either saw, or suspected, that the Fancher-Baker party poisoned a spring and a dead ox, later eaten by Native Americans.[105][106] The trial ended in a hung jury on August 5 1875.

Lee's second trial began September 13 1876, before an all-Mormon jury. The prosecution called Daniel Wells, Laban Morrill, Joel White, Samuel Knight, Samuel McMurdy, Nephi Johnson, and Jacob Hamblin.[107] Lee also stipulated, against advice of counsel, that the prosecution be allowed to re-use the depositions of Young and Smith from the previous trial.[108] Lee called no witnesses in his defense.[109] This time, Lee was convicted.

(seated next to coffin)

At his sentencing, as required by Utah Territory statute, he was given the option of being hung, shot, or beheaded, and he chose to be shot.[110] In 1877, executed by firing squad at Mountain Meadows (a fate Young believed just, but not a sufficient blood atonement, given the enormity of the crime, to get him into the celestial kingdom).[111] Lee himself professed that he was a scapegoat for others involved.

I have always believed, since that day, that General George A. Smith was then visiting Southern Utah to prepare the people for the work of exterminating Captain Fancher's train of emigrants, and I now believe that he was sent for that purpose by the direct command of Brigham Young.

The knowledge of how George A. Smith felt towards the emigrants, and his telling me that he had a long talk with Haight on the subject, made me certain that it was the wish of the Church authorities, that Fancher and his train should be wiped out, and knowing all this, I did not doubt then, and I do not doubt it now, either, that Haight was acting by full authority from the Church leaders, and that the orders he gave to me were just the orders that he had been directed to give, when he ordered me to raise the Indians and have them attack the emigrants.[112]

Media coverage and commentary

Although the massacre was covered to some extent in the media during the 1850s,[citation needed], the first period of intense nation-wide publicity about the massacre began around 1872, after investigators obtained the confession of Philip Klingensmith, a Mormon bishop at the time of the massacre and a private in the Utah militia. In 1872, Mark Twain commented on the massacre through the lens of contemporary American public opinion in an appendix[113] to his semi-autobiographical travel book Roughing It. In 1873, the massacre was a prominent feature of a history by T.B.H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints.[114] National newspapers covered the Lee trials closely from 1874 to 1876, and his execution in 1877 was widely covered.

The massacre has been treated extensively by several historical works, beginning with Lee's own Confession in 1877, expressing his opinion that George A. Smith was sent to southern Utah by Brigham Young to direct the massacre.[115] In 1910, the massacre was the subject of a short 1910 book by Josiah F. Gibbs, who also attributed responsibility for the massacre to Young and Smith.[116] The first detailed and comprehensive work using modern historical methods was Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1950 by Juanita Brooks, a Mormon scholar who lived near the area in southern Utah. Brooks found no evidence of direct involvement by Brigham Young, but charged him with obstructing the investigation and for provoking the attack through his rhetoric.

The most significant works after Brooks include the book Blood of the Prophets by Will Bagley in 2002[117] and American Massacre by Sally Denton in 2003.[118] Bagley pointed to what he said was strong circumstantial evidence of Young's involvement through Smith, and through his early September 1857 meeting with Paiute Indian leaders Tutsegabit and Youngwids.[citation needed] Denton also suggested involvement by Young through Smith, but argued against involvement by Paiute leaders.[citation needed]

In historical fiction, the massacre inspired a genre of frontier crime fiction in the 19th century. The massacre has been portrayed in several plays, and in a 2007 motion picture, September Dawn. A documentary entitled Burying the Past: Legacy of the Mountain Meadows Massacre (2004) covers the massacre, the descendants of the victims and perpetrators, and the forensic evidence discovered at the massacre site.

LDS public relations

After a period of official public silence concerning the massacre, and denials of any Mormon involvement, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) took action in 1872 to excommunicate some of the participants for their role in the massacre. Since then, the LDS Church has consistently condemned the massacre, though acknowledging involvement by local Mormon leaders. In September 2007, the LDS Church published an article in its official publications marking 150 years since the tragedy occurred.[119].

Beginning in the late mid- to late-20th century, the LDS Church has made efforts to reconcile with the descendents of John D. Lee (reinstating him posthumously to full fellowship in the church), as well as those of the slain Fancher-Baker party. The church erected a memorial at the massacre site in 1999, and has opened many of its previously confidential archival records about the massacre to scholars.

Commemorations

Non-Mormon markers and memorials at Mountain Meadows

Mountain Meadows

Photograph taken in 1898.

Stones of this marker scattered at least twice by vandals during

19th century[120]

The original cairn Major Carleton had erected over the victims' mass graves on May 20 1859 contained a granite marker inscribed with the words, Here 120 men, women, and children were massacred in cold blood early in September 1857. They were from Arkansas, along with a cedar cross bearing the words, Vengeance is mine. I will repay, saith the Lord.[48] This marker was soon torn down by Brigham Young,[citation needed] then re-built in 1864 by the U.S. military, then torn down again around 1874.[121] In 1932 a memorial wall was built around the 1859 Cairn.[122] In 1990, the Mountain Meadows Association built a monument overlooking the Mountain Meadows massacre site, it is maintained by the Utah State Division of Parks and Recreation[122][123].

On September 15 1990, more than 2,000 people attended a memorial service at Southern Utah State College, marking the dedication of the memorial. Participants in the memorial service included Judge Roger V. Logan, Jr. of Harrison, Arkansas and J. K. Fancher representing the emigrant families, tribal chairwoman Geneal Anderson and spiritual leader Clifford Jake, representing the Paiute tribe, Rex E. Lee, representing descendants of LDS pioneer families from the area, and a then–first counselor in the LDS First Presidency Gordon B. Hinckley representing the church.

According to quotes from an article in the Saint George, Utah, Spectrum newspaper:[124]

J.K. Francher, a Harrison, Ark., pharmacist and freelance writer, said...[that he] never dreamed that a memorial service would come to fruition but "the spirit kicked in" and people of differing religious beliefs have reconciled. "The most difficult words for men to utter is 'I'm sorry and I forgive you'."Easing the burden of the victims was also the goal of Paiute Indian Tribal Chairwoman Geneal Anderson of Cedar City....

During the ceremony, descendants of both the victims and perpetrators joined arms on stage and in the audience, some hugging and embracing each other following a challenge by Rex E. Lee, Brigham Young University president.... Gordon B. Hinckley...said he came as a representative of a church that has suffered much over what happened. While people can't comprehend what occurred...Hinckley said he was grateful for reconciliation by the descendants on both sides...."Now if there is need for forgiveness, we ask that it be granted."

Commemorations in Arkansas

Mountain Meadows

erected in 2005 in Carrollton, Arkansas

A marker was placed in the Carrollton, Arkansas town square in 1955 in commemoration of the surviving children's return to their next of kin there in 1859—to which (elsewhere in Carrollton) a replica of Carleton's original wooden cross and cairn was added in 2005.

A commemorative wagon-train encampment assembled at Beller Spring, Arkansas on April 21–22, 2007, with some participants in period dress, to honor the sesquicentennial of their ancestors' embarkation on the ill-fated journey.[125]

LDS Church's 1999 memorial

In 1999 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built and agreed to maintain a second monument at Mountain Meadows.[126] During excavation for the monument, however, a backhoe moving a wall originally erected by Carleton accidentally unearthed the remains of at least 29 victims, allowing anthropologists to conduct forensic examinations.

The Mountain Meadows Foundation, based in Arkansas, was wary of the LDS Church's sole ownership of the property and oversight of the memorial. It sought to buy this area, encompassing three different emigrant gravesites, from its owner, the LDS church, to be administered through an independent trustee or else for the property to be kept in the LDS church's hands but for it to be leased to the federal government for oversight as a national monument. The church declined this idea, yet bought more parcels nearby as a preserve from resorts development.[127] During ceremonies dedicating the monument, Hinckley said, "That which we have done here must never be construed as an acknowledgment of the part of the church of any complicity in the occurrences of that fateful day."

150th Anniversary

On September 11, 2007, approximately 400 people, including many descendants of those slain at Mountain Meadows, gathered to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the massacre. At this commemoration, Elder Henry B. Eyring of the LDS Church's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles issued a statement on behalf of the LDS Church's First Presidency expressing regret for the actions of local church leaders in the massacre. During the commemoration, Elder Eyring stated, "We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today, and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their relatives to the present time... What was done here long ago by members of our church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teachings and conduct. We cannot change what happened, but we can remember and honor those who were killed here." [128] [129] [130]

Notes

- ^ Stenhouse 1873, p. 425.

- ^ The Utah Territory militia technically included every able-bodied Mormon in the region between ages eighteen and forty-five (Shirts 1994; MacKinnon 2007

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 214.

- ^ Hamblin 1876 stated he buried over 120 skeletons); James Lynch (1859) reported there were 140 victims; in Thompson 1860, p. 8,82, Superintendent Forney reported 115 victims; a 1932 monument states about 140 were involved in the massacre less 17 children spared; while Brooks' (introduction, 1991) believes 123 to be exaggerated, citing several reports of less than 100. The 1990 monument lists 82 identified by careful research of descendants of survivor ([1] and states that there are others still unknown. See also Bagley 2002.

- ^ In 1856, Young said "the government of God, as administered here" may to some seem "despotic" because "[i]t lays the ax at the root of the tree of sin and iniquity; judgment is dealt out against the transgression of the law of God"; however, "does not [it] give every person his rights?" Young 1856, p. 256.

- ^ Stenhouse 1873, p. 431 (citing "Argus", an anonymous contributor to the Corinne Daily Reporter whom Stenhouse met and vouched for).

- ^ Turley 2007.

- ^ Turley 2007.

- ^ see Mountain Meadows Massacre Leader in Tietoa Mormonismista Suomeksi.)

- ^ Turley 2007.

- ^ Burns & Ives 1996, Episode 4; Salt Lake City Messenger #88; Mountain Meadows Massacre: An Aberration of Mormon Practice

- ^ Turley 2007.

- ^ James H. Martineau, "The Mountain Meadow Catastrophy", July 23 1907, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ^ James H. Martineau, "The Mountain Meadow Catastrophy", July 23 1907, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 214.

- ^ Klingensmith affidavit.

- ^ Briggs 2006, pp. 323–24. Lee said this meeting probably took place late on a Sunday, which would be September 6, but because this date would conflict with statements by other witnesses.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Briggs 2006, p. 322.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Morrill 1876.

- ^ Gibbs 1910, pp. 53–54 (statement to Gibbs by Benjamin Platt, an employee at Lee's home who said he did not participate in the massacre).

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 50 Bigler 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 226-227 Lee said the first attack occurred on a Tuesday and the Native Americans were several hundred strong.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

shirtswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gibbs 1910, pp. 54 (statement to Gibbs by Benjamin Platt, a Lee employee, who said he heard details of the massacre from Lee at a church meeting after the massacre).

- ^ Andrew Jenson, notes of discussion with William Barton, Jan. 1892, Mountain Meadows file, Jenson Collection, Church Archives

- ^ "Remembering Mountain Meadows", published in the LDS Church's Church News 23 June 2007, with information gleaned from lectures by historians Ron Walker and Richard Turley on a bus tour of the massacre site on 28 May

- ^ Gibbs 1910, p. 230

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 51

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 236

- ^ Carleton 1859

- ^ Gibbs 1910 relates a story by a Mormon woman who was a child at the time of the massacre fifty years earlier. She recalled hearing LDS women in St. George, about 15 miles from the Mountain Meadows, say both girls were raped before they were killed. This allegation is repeated in Denton 2003. Juanita Brooks Brooks 1950, p. 105, in The Mountain Meadows Massacre discounts the rape story and recounts an eyewitness account confirming the Dunlap girls' murders without any further allegations. She argues that "circumstances surrounding the massacre make [...rape] highly improbable....surrounded by excited Indians, with more than fifty Mormon men in the immediate vicinity." Brooks also wrote the biography that was commissioned by the Lee family.

- ^ Fanchers Who Died In The Mountain Meadows Massacre, rootsweb.com, 2007, retrieved 2007-08-21

{{citation}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Nancy Saphrona Huff at Burying the Past: Legacy of the Mountain Meadows Massacre website

- ^ Multiple sources claim that Lee protested and prohibited the death of all children that were assumed to be under the age of eight, and directed that they be placed in the care of one who was not involved in the massacre. See for example, on page 231 of Mormonism unveiled. Not all of the young children were spared, however; at least one infant was killed in his father's arms by the same bullet that killed the adult man Lee 1877, p. 241.

- ^ Klingensmith 1872.

- ^ Klingensmith 1872 (naming himself, McMurdy, and Willis); Lee 1877, p. 243 (naming Knight and McMurdy).

- ^ Carleton 1859 ("... when [Mrs. Hamblin] told of the 17 orphan children who were brought by such a crowd to her house of one small room there in the darkness of night, two of the children cruelly mangled and the most of them with their parents' blood still wet upon their clothes, and all of them shrieking with terror and grief and anguish, her own mother heart was touched."); Klingensmith 1872; Klingensmith 1875.

- ^ Klingensmith 1872.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 245.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 247.

- ^ Bagley 2002, p. 158 (relating account of militiaman Nephi Johnson); Lee 1877, p. 248.

- ^ a b Carleton 1859, p. p.15.

- ^ Weekly Stockton Democrat; 5 June 1859. "Both [Becky Dunlap] and a boy named Miram recognized dresses and a part of the jewelry belonging to their mothers, worn by the wives of John D. Lee, the Mormon Bishop of Harmony. The boy, Miram, identified his father's oxen, which are now owned by Lee."

- ^ Bagley 2002, p. 134-139; Brooks 1950, p. 138-139; Denton 2003, p. 164-165; Thompson 1860, p. 15

- ^ Brigham Young to Isaac C. Haight, 10 September 1857, Letterpress Copybook 3:827–28, Brigham Young Office Files, LDS Church Archives.

- ^ James H. Haslam, interview by S. A. Kenner, reported by Josiah Rogerson, 4 December 1884, typescript, 11, in Josiah Rogerson, Transcripts and Notes of John D. Lee Trials, LDS Church Archives.

- ^ Brooks, "The Mountain Meadows Massacre" p. 219

- ^ See [2] this review of Bagley's book by Jeff Needle of the Association of Mormon Letters where this subject is debated.

- ^ Shirts 1994

- ^ MacKinnon 2007, p. 57

- ^ Bagley 2002, p. 247.

- ^ MacKinnon 2007, p. endnote 50

- ^ Brooks\1950.

- ^ Brooks\1950.

- ^ John W. Young affidavit (1884)

- ^ Hamblin 1876.

- ^ Young 1875.

- ^ Young 1875.

- ^ Bagley 2002, p. 157

- ^ http://www.sidneyrigdon.com/dbroadhu/CA/misccal1.htm#100357

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 118

- ^ Stoffle & Evans 1978, p. 57

- ^ Cuch 2000, p. 137-138

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 67, 170, 172 Klingonsmith admitted that he saw one hundred of them present. Nephi Johnson reports one-hundred and fifty Native Americans present. Hibgee estimates "anywhere from three to six hundred. Lee 1877, p. 226 Lee states at least two hundred were present.

- ^ Whitney & Barnes 2007.

- ^ Hamilton 1857.

- ^ Thompson 1860, p. 96-97.

- ^ Letters From Nevada Indian Agents - 1857. Available online here.

- ^ Hamblin 1876.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 259.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 214.

- ^ Young 1875.

- ^ Diary of Wilford Woodruff (Brooks 1950, p. 104); Affidavit of John W. Young (1884) (saying the meeting took place "in the latter part of September, 1857"). Brigham Young was mistaken when he later testified that the meeting took place "some two of three months after the massacre" Young 1875.

- ^ Young 1875.

- ^ Hamblin 1876.

- ^ See Message of the President. December 4 1859. Hurt to Forney. Also see Bagley, p. 113.

- ^ Forney 1859, p. 1.

- ^ Fisher 2003.

- ^ Rogers 1860

- ^ Thompson 1860 Capt. Campbell p.15, J.Forney p.79

- ^ Bagley 2002, p. p.237

- ^ Thompson 1860p. 57, 71

- ^ After the massacre, the decision was made to take the children to the nearby Hamblin home; however, Hamblin was gone at the time of the killings. Hamblin's testimony in this regard is as following (Q=attorney in Lee's trial; A=Hamblin):

"Q: What became of the children of those emigrants? How many children were brought there?

A: Two to my house, and several in Cedar City. I was acting subagent for Forney. I gathered the children up for him; seventeen in number, all I could learn of.

Q: Whom did you deliver them to?

A: Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah." [3] - ^ Brooks, pp. 78–79

- ^ Carleton, 1859 & p.14

- ^ Forney 1859, p. 1;

- ^ Carleton 1859

- ^ Carleton 1859.

- ^ Cradlebaugh 1859, p. 3; Carrington 1859, p. 2.

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 133

- ^ Briggs 2006, p. 315

- ^ Lee was arrested on November 7 1874. "John D. Lee Arrested", Deseret News, November 18 1874, p. 16.

- ^ Tragedy at Mountain Meadows Massacre: Toward a Consensus Account and Time Line

- ^ "The Lee Trial", Deseret News, July 28 1875, p. 5.

- ^ "The Lee Trial", Deseret News, August 25 1875, p. 1.

- ^ Smith 1875.

- ^ Young 1875.

- ^ Not the same Philo T. Farnsworth as the inventor born in 1906

- ^ Case of the Defense", Salt Lake Tribune, 3 August 1875; Briggs 2006, p. 320.)

- ^ Brooks 1950, p. 105 "The poisoned meat story was unlikely, while the poisoned springs was quite clearly fabrication; to poison a running stream of any size would take a great amount of poison, and if several Saints had died, their names and homes and other details would have been given."

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 317–78.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 302–03.

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 378.

- ^ "Territorial Dispatches: the Sentence of Lee", Deseret News, October 18 1876, p. 4.

- ^ Young 1877, p. 242) (Young was asked after Lee's execution if he believed in blood atonement. Young replied, "I do, and I believe that Lee has not half atoned for his great crime".)

- ^ Lee 1877, p. 225-226.

- ^ Appendix B

- ^ Stenhouse 1873.

- ^ Lee 1877.

- ^ Gibbs 1910.

- ^ Bagley 2002

- ^ Denton 2003.

- ^ Richard E. Turley Jr., The Mountain Meadows Massacre, lds.org, 2007-08-29

- ^ "Mountain Meadows Monument, Salt Lake Tribune, May 27 1874.

- ^ "Mountain Meadows Monument, Salt Lake Tribune, May 27 1874.

- ^ a b Morris A. Shirts (2007). "Mountain Meadows Massacre" (HTML). Utah History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

The most enduring was a wall which still stands at the siege site. It was erected in 1932 and surrounds the 1859 cairn.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Mountain Meadows Association - 1990 MONUMENT" (HTML). Mountain Meadows Association. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Webb 1990

- ^ Brown, Barbara Jones (April 24, 2007). "Mountain Meadows relatives mark 150th anniversary". Deseret Morning News. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ See pictures at 1999 Monument.

- ^ Mountain Meadows reconciliation, editorial in The (Provo, Utah) Daily Herald; 19 June 2007

- ^ Eyring expresses regret for pioneer massacre [4]

- ^ Ravitz, Jessica, LDS Church Apologizes for Mountain Meadows Massacre, Salt Lake Tribune; 11 September 2007

- ^ First Presidency's Mountain Massacre Anniversary Statement, Salt Lake Tribune; 11 September 2007

References

- Abanes, Richard (2003), One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, ISBN 1568582838.

- Bagley, Will (2002), Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3426-7.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1889), The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Utah, 1540–1886, vol. 26, San Francisco: History Company, LCC F826.B2 1889, LCCN 07018413 (Internet Archive versions).

- Beadle, John Hanson (1870), "Chapter VI. The Bloody Period.", Life in Utah, Philadelphia: National Publishing, LCC BX8645 .B4 1870, LCCN 30005377, at 177-195.

- Bigler, David (1998), Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896, Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, ISBN 0-87421-245-6.

- Briggs, Robert H. (2006), "The Mountain Meadows Massacre: An Analytical Narrative Based on Participant Confessions", Utah Historical Quarterly 74 (4): 313-333.

- Brooks, Juanita (1950), Mountain Meadows Massacre, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2318-4.

- Buerger, David John (2002), The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship (2nd ed.), Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1560851767.

- Burns, Ken & Stephen Ives (1996), New Perspectives on the West (Documentary), Washington, D.C.: PBS.

- Cannon, Frank J. & George L. Knapp (1913), Brigham Young and His Mormon Empire, New York: Fleming H. Revell Co..

- Carleton, James Henry (1859), Special Report on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, Washington: Government Printing Office (published 1902).

- Carrington, Albert, ed. (April 6 1859), "The Court & the Army", Deseret News 9 (5): 2.

- Carrington, Albert, ed. (1 December 1869), "Mountain Meadows Massacre", Deseret News 18 (43): 6–7.

- Christian, J. Ward (October 4 1857), Letter to G.N. Whitman, at San Bernardino, in Hamilton, Henry, "Horrible Massacre of Arkansas and Missouri Emigrants", Los Angeles Star, October 10 1857.

- Cradlebaugh, John (March 29 1859), Anderson, Kirk, ed., "Discharge of the Grand Jury", Valley Tan 1 (22): 3.

- Cradlebaugh, John (February 7, 1863), Utah and the Mormons: a Speech on the Admission of Utah as a State, 37th United States Congress, 3rd Session.

- Crockett, Robert D. (2003), "A trial lawyer reviews Will Bagleys' Blood of the Prophets", FARMS Review 15 (2): 199-254.

- Cuch, Forrest S. (2000). History of Utah's American Indians. Salt Lake City: Utah State Division of Indian Affairs : Utah State Division of History : Distributed by Utah State University Press, pp.131-139. ISBN 0-913738-48-4. OCLC 45321868. Retrieved on 2007-07-08. .

- Denton, Sally (2003), American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0-375-41208-5. Washington Post review and Letter to the editor in response to the review.

- Dunn, Jacob Piatt (1886), Massacres of the Mountains: A History of the Indian Wars of the Far West, New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Erickson, Dan (1996), "Joseph Smith's 1891 Millennial Prophecy: The Quest for Apocalyptic Deliverance", Journal of Mormon History 22 (2): 1–34.

- Fancher, Lynn-Marie & Alison C. Wallner (2006), 1857: An Arkansas Primer To The Mountain Meadows Massacre.

- Fillmore, Millard (September 26 1850), "I nominate Brigham Young, of Utah, as governor of the Territory of Utah", in McCook, Anson G., Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, vol. 8, Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1887, at 252

- Finck, James (2005), "Mountain Meadows Massacre", in Dillard, Tom W., Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas: Encyclopedia of Arkansas Project.

- Fisher, Alyssa (2003-09-16), "A Sight Which Can Never Be Forgotten", Archaeology.

- Ford, Thomas (1854), A History of Illinois, from its Commencement as a State in 1818 to 1847, Chicago: S.C. Griggs & Co..

- Forney, J[acob]. (May 5 1859), "Visit of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs to Southern Utah", Deseret News 9 (10): 1, May 11 1859.

- Gibbs, Josiah F. (1910), The Mountain Meadows Massacre, Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Tribune, LCC F826 .G532 LCCN 37010372.

- Grant, Jedediah M. (March 12, 1854), "Discourse", Deseret News 4 (20): 1–2, July 27 1854.

- Grant, Jedediah M. (April 2 1854), "Fulfilment of Prophecy—Wars and Commotions", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 2, Liverpool: F.D. & S.W. Richards, 1855, at 145–49.

- Hamblin, Jacob (September 1876), "Testimony of Jacob Hamblin", in Linder, Douglas, Mountain Meadows Massacre Trials (John D. Lee Trials) 1875–1876, University of Missouri-Kansas School of Law, 2006.

- Hamblin, Jacob (1881), "Jacob Hamblin: A Narrative of His Personal Experience", Faith Promoting Series, vol. 5.

- Hamilton, Henry, ed. (1857), "Horrible Massacre of Arkansas and Missouri Emigrants", Los Angeles Star (published October 10 1857).

- Higbee, John M. (February 1894), "Statement", in Brooks, Juanita, Mountain Meadows Massacre, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2318-4, at 226–35.

- Huntington, Dimick B. (1857), Journal, LDS Archives, Ms d. 1419.

- Hurt, Garland (October 24 1857), Letter from Garland Hurt, Utah Territorial Indian Agent, to Col. A.S. Johnston, U.S. Army.

- Kimball, Heber C. (January 11 1857), "The Body of Christ-Parable of the Vine-A Wile Enthusiastic Spirit Not of God-The Saints Should Not Unwisely Expose Each Others' Follies", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, and the Twelve Apostles, vol. 4, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1857, at 164–81.

- Kimball, Heber C. (August 16 1857), "Limits of Forebearance-Apostates-Economy-Giving Endowments", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, and the Twelve Apostles, vol. 4, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1857, at 374–76.

- Kimball, Heber C. (August 28 1859), "Greater Responsibilities of Those Who Know the Truth, &c.", in Lyman, Amasa, Journal of Discourses Delivered by President Brigham Young, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 7, Liverpool: Amasa Lyman, 1860, at 231–37.

- Klingensmith, Philip (September 5 1872), Affidavit, at Lincoln County, Nevada, in Toohy, Dennis J., "Mountain Meadows Massacre", Corinne Daily Reporter (Corinne, Utah) 5 (252): 1, September 24 1872.

- Klingensmith, Philip (July 23–24, 1875), at Beaver City, Utah, Testimony, First trial of John D. Lee, Braintree, MA: Mountain Meadows Association.

- Lee, John D. (1877), Bishop, William W., ed., Mormonism Unveiled; or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee, St. Louis, Missouri: Bryan, Brand & Co..

- Linn, William Alexander (1902), The Story of the Mormons: From the Date of their Origin to the Year 1901, New York: McMillan (scanned versions).

- Lynch, James (July 22 1859), Affidavit of James Lynch Regarding the Mountain Meadows Massacre September 1857 Sworn Testimony; also included in Brooks (1991) Appendix XII.

- MacKinnon, William P. (2003), "'Like Splitting a Man Up His Backbone': The Territorial Dismemberment of Utah", Utah Historical Quarterly 71 (2): 1850–96.

- MacKinnon, William P. (2007), "Loose in the stacks, a half-century with the Utah War and its legacy", Dialogue, a journal of Mormon thought 40 (1): 43–81.

- Martineau, James H. (August 22 1857), at Parowan, Utah Territory, "Correspondence: Trip to the Santa Clara", Deseret News 9 (5): 3, September 23 1857.

- McMurtry, Larry (2005), Oh what a slaughter : massacres in the American West, 1846-1890, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN ISBN 074325077X. BookReporter.com review.

- Melville, J. Keith (1960), "Theory and Practice of Church and State During the Brigham Young Era", BYU Studies 3 (1): 33–55.

- Mitchell, William C. (April 26 1860), List of the Mountain Meadows Massacre Victims, Letter to A. B. Greenwood, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Washington, D.C..

- Morrill, Laban (September 1876), "Laban Morrill Testimony—witness for the prosecution", in Linder, Douglas, Mountain Meadows Massacre Trials (John D. Lee Trials) 1875–1876, University of Missouri-Kansas School of Law, 2006.

- Novak, Shannon & Lars Rodseth (2006), "Remembering Mountain Meadows: Collective violence and manipulation of social boundaries", Journal of Anthropological Research 62 (1): 1-25, ISSN 0091-7710.

- Parshall, Ardis E. (2005), "'Pursue, Retake and Punish': The 1857 Santa Clara Ambush", Utah Historical Quarterly 73 (1): 64-86.

- Penrose, Charles W. (July 4 1883), "An Unpardonable Offense", Deseret News 32 (24): 376.

- Pratt, Parley P. (December 31 1855), "Marriage and Morals in Utah", Deseret News 5 (45): 356–57, January 16 1856.

- Pratt, Steven (1975), "Eleanor McLean and the Murder of Parley P. Pratt", BYU Studies 15 (2): 225–56.

- Prince, Gregory A. & Wm. Robert Wright (2005), David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874808227.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1997), 'The Mormon hierarchy : extensions of power.' Salt Lake City : Signature Books in association with Smith Research Associates. ISBN 1-56085-060-4.

- Quinn, D. Michael (2001), "LDS 'Headquarters Culture' and the Rest of Mormonism: Past and Present", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 34 (3–4): 135–64.

- Rogers, Wm. H. (February 29 1860), "The Mountain Meadows Massacre", Valley Tan 2 (16): 2–3; also included in Brooks (1991) Appendix XI.

- Scott, Malinda Cameron (1877). Malinda (Cameron) Scott Thurston Deposition. Mountain Meadows Association. Retrieved on 2007-06-15.

- Sessions, Gene (2003), "Shining New Light on the Mountain Meadows Massacre", FAIR Conference 2003.

- Shirts, Morris (1994), "Mountain Meadows Massacre", in Powell, Allen Kent, Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Smart, Donna T. (1994), "Parley Parker Pratt", in Powell, Allen Kent, Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Smith, Christopher (January 21, 2001), "Forensic Study Aids Tribe's View Of Mountain Meadows Massacre", Salt Lake Tribune: A1, ISSN 0746-3502.

- Smith, George A. (September 13 1857), "Report of a Visit to the Southern Country", in Calkin, Asa, 1858, at 221–25.

- Smith, George A. (July 30 1875), at Salt Lake City, "Deposition, People v. Lee", Deseret News 24 (27): 8, August 4 1875.

- Stenhouse, T.B.H. (1873), The Rocky Mountain Saints: a Full and Complete History of the Mormons, from the First Vision of Joseph Smith to the Last Courtship of Brigham Young, New York: D. Appleton, ID=LCC BX8611 .S8 1873, LCCN 16024014, ASIN: B00085RMQM.

- Stoffle, Richard W; Michael J Evans (1978). Kaibab Paiute history : the early years. Fredonia, Ariz.: Kaibab Paiute Tribe, p. 57. OCLC 9320141. .

- Thompson, Jacob (1860), Message of the President of the United States: communicating, in compliance with a resolution of the Senate, information in relation to the massacre at Mountain Meadows, and other massacres in Utah Territory, 36th Congress, 1st Session, Exec. Doc. No. 42, Washington, D.C..

- Turley, Richard E., Jr. (September 2007), "The Mountain Meadows Massacre", Ensign, Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ISSN 0884-1136.

- Twain, Mark (1873), Roughing It, Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing.

- Waite, C.V. (Catherine Van Valkenburg) (1868), The Mormon Prophet and His Harem: Or, an Authentic History of Brigham Young, His Numerous Wives and Children, Chicago: J.S. Goodman & Co..

- Walker, Ronald W. (2003), ""Save the emigrants," Joseph Clewes on the Mountain Meadows massacre", BYU studies 42 (1): 139-152

- Webb, Loren (September 16, 1990), "Time for healing, LDS leader says about massacre", Saint George Spectrum:

- Whitney, Helen & Jane Barnes (2007), The Mormons (Documentary), Washington, D.C.: PBS.

- Young, Brigham; Heber C. Kimball & Orson Hyde et al. (April 6 1845), Proclamation of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ, of Latter-Day Saints, New York: LDS Church.

- Young, Brigham (February 5 1852), Speach by Gov. Young in Joint Session of the Legeslature (sic), Brigham Young Addresses, Ms d 1234, Box 48, folder 3, LDS Church Historical Department, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Young, Brigham (July 8 1855), "The Kingdom of God", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 2, Liverpool: F.D. & S.W. Richards, 1855, at 309–17.

- Young, Brigham (March 2, 1856a), "The Necessity of the Saints Living up to the Light Which Has Been Given Them", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 3, Liverpool: Orson Pratt, 1856, at 221–226.

- Young, Brigham (March 16, 1856b), "Instructions to the Bishops—Men Judged According to their Knowledge—Organization of the Spirit and Body—Thought and Labor to be Blended Together", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 3, Liverpool: Orson Pratt, 1856, at 243–49.

- Young, Brigham (March 16, 1856c), "Difficulties Not Found Among the Saints Who Live Their Religion—Adversity Will Teach Them Their Dependence on God—God Invisibly Controls the Affairs of Mankind", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 3, Liverpool: Orson Pratt, 1856, at 254–60.

- Young, Brigham (September 21, 1856d), "The People of God Disciplined by Trials—Atonement by the Shedding of Blood—Our Heavenly Father—A Privilege Given to all the Married Sisters in Utah", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, and the Twelve Apostles, vol. 4, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1857, at 51–63.

- Young, Brigham (February 8, 1857b), "To Know God is Eternal Life—God the Father of Our Spirits and Bodies—Things Created Spiritually First—Atonement by the Shedding of Blood", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, and the Twelve Apostles, vol. 4, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1857, at 215–21.

- Young, Brigham (July 5, 1857c), "True Happiness—Fruits of Not Following Counsel—Popular Prejudice Against the Mormons—The Coming Army—Punishment of Evildoers", in Calkin, Asa, Journal of Discourses Delivered by President Brigham Young, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 5, Liverpool: Asa Calkin, 1858, at 1–6.

- Young, Brigham (July 26, 1857d), "Nebuchadnezzar's Dream—Opposition of Men and Devils to the Latter-Day Kingdom—Governmental Breach of the Utah Mail Contract", in Calkin, Asa, Journal of Discourses Delivered by President Brigham Young, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, vol. 5, Liverpool: Asa Calkin, 1858, at 72–78.

- Young, Brigham (August 5, 1857a), Proclamation by the Governor, Salt Lake City: Utah Territory.

- Young, Brigham (April 7, 1867), "Word of wisdom", in Watt, G.D., Journal of Discourses by Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, His Two Counsellors, and the Twelve Apostles, vol. 12, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1869, at 27.

- Young, Brigham (July 30, 1875), at Salt Lake City, "Deposition, People v. Lee", Deseret News 24 (27): 8, August 4 1875.

- Young, Brigham (April 30, 1877), "Interview with Brigham Young", Deseret News 26 (16): 242–43, May 23 1877.

External links

- Mountain Meadows Association – "An unusual mix of historians and descendants of massacre victims and perpetrators" (The Salt Lake Tribune).

- An account of the Mountain Meadows Massacre from the Court TV Crime Library

- Background articles from Comprehensive History of the Church, Messages of the First Presidency - President Wilford Woodruff, and The Restored Church

- Images of the current Mountain Meadows monument and surrounding area

- Paiute Indians on Utah.gov

- Mark Twains Accounts of the Goshutes, a Uto-Aztecan Tribe (Ute/Paiute) in Utah.

- Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought Search the site for many references to Mountain Meadows massacre; research, articles, and personal interview with Juanita Brooks by Mormon scholars and noted historians.

- LDS Account