Thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also called an electrical storm or lightning storm, is a form of weather characterized by the presence of lightning and its attendant thunder.[1] The lightning in a thunderstorm is caused by an electrical charge that builds up inside the storm due to the movement of water droplets or crystals carried by the wind. Thunderstorms are usually accompanied by heavy rainfall (heavy downpours), strong winds, hail, and sometimes tornadoes. During winter months, snowfall occasionally takes place in a thunderstorm, an occurrence sometimes termed thundersnow.

Life cycle

As the air begins to lift, it eventually starts to cool and condensation takes place. When the moisture condenses, heat is released which further aids in the lifting process. If enough instability is present in the atmosphere, this process will continue long enough for cumulonimbus clouds to form, which supports lightning and thunder.

All thunderstorms, regardless of type, go through three stages: the cumulus stage, the mature stage, and the dissipation stage. Depending on the conditions present in the atmosphere, these three stages can take anywhere from 20 minutes to several hours to occur.

Cumulus stage

The first stage of thunderstorm is the cumulus stage, or developing stage. In this stage, masses of moisture are lifted upwards into the atmosphere. The trigger for this lift can be insolation heating the ground producing thermals, areas where two winds converge forcing air upwards, or where winds blow over terrain of increasing elevation. The moisture rapidly cools into liquid drops of water, which appears as cumulus clouds. As the water vapor condenses into liquid, latent heat is released which warms the air, causing it to become less dense than the surrounding dry air, and so the air will tend to rise in an updraft due to the process of convection (hence the term convective precipitation). This creates a low-pressure zone beneath the forming thunderstorm. In a typical thunderstorm, some 5×108 kg of water vapour are lifted and the amount of energy released when this condenses is about equal to the energy used by a city (US-2002) of 100,000 during a month.

Mature stage

In the mature stage of a thunderstorm, the warmed air continues to rise until it reaches existing air which is itself warmer, and the air can rise no further. Often this 'cap' is the tropopause. The air is instead forced to spread out, giving the storm a characteristic anvil shape. The resulting cloud is called cumulonimbus incus. The water droplets coalesce into heavy droplets and freeze to become ice particles. As these fall they melt, to become rain. If the updraft is strong enough, the droplets are held aloft long enough to be so large that they do not melt completely as they fall and fall as hail. While updrafts are still present, the falling rain creates downdrafts as well. The simultaneous presence of both an updraft and downdrafts marks the mature stage of the storm, and during this stage considerable internal turbulence can occur in the storm system, which sometimes manifests as strong winds, severe lightning, and even tornadoes.

Typically, if there is little wind shear, the storm will rapidly enter the dissipating stage and 'rain itself out', but if there is sufficient change in wind speed and/or direction the downdraft will be separated from the updraft, and the storm may become a supercell and the mature stage can sustain itself for several hours.

In certain cases however, even with little wind shear, if there is enough atmospheric support and instability in place for the thunderstorm to feed on, it may even maintain its mature stage a bit longer than most storms.

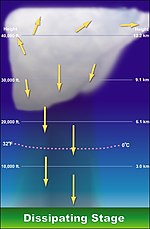

Dissipating stage

In the dissipation stage, the thunderstorm is dominated by the downdraft. If atmospheric conditions do not support super cellular development, this stage occurs rather quickly, some 20-30 minutes into the life of the thunderstorm. The downdraft will push down out of the thunderstorm, hit the ground and spread out. The cool air carried to the ground by the downdraft cuts off the inflow of the thunderstorm, the updraft disappears and the thunderstorm will dissipate.

Classification

There are four main types of thunderstorms: single cell, multicell, squall line (also called multicell line) and supercell. Which type forms depends on the instability and relative wind conditions at different layers of the atmosphere ("wind shear").

Single cell

This term technically applies to a single thunderstorm with one main updraft. Within a cluster of thunderstorms, the term "cell" refers to each separate principal updraft.

Thunderstorm cells can and do form in isolation to other cells. Such storms are rarely severe and are a result of local atmospheric instability; hence the term "air mass thunderstorm". These are the typical summer thunderstorm in many temperate locales. They also occur in the cool unstable air which often follows the passage of a cold front from the sea during winter.

While most single cell thunderstorms move, there are some unusual circumstances where they don't. When this happens, catastrophic flooding is possible. In Rapid City, South Dakota in 1972, an unusual alignment of winds at various levels of the atmosphere combined to produce a continuous, stationary cell which dropped an enormous quantity of rain, resulting in devastating flash flooding [1]. A similar event occurred in Boscastle, England on the 16th of August 2004 [2].

Multicell cluster

Multi cell storms form as clusters of storms but may then evolve into an organized line or lines of storms. They often arise from convective updrafts in or near mountain ranges and linear weather boundaries, usually strong cold fronts or troughs of low pressure.ok

Multicell lines

Multicell line storms, commonly referred to as "squall lines", occur when multi cellular storms form in a line rather than clusters. They can be hundreds of miles long, move swiftly, and be preceded by a gust front. Heavy rain, hail, lightning, very strong winds and even isolated tornadoes can occur over a large area in a squall line.[2] Bow echoes can form within squall lines, bringing with them even higher winds.

An unusually powerful type of squall line called a derecho occurs when an intense squall line travels for several hundred miles, often leaving widespread damage over thousands of square miles.

Occasionally, squall lines also form near the outer rain band of tropical cyclones. The squall line is propelled by its own outflow, which reinforces continuous development of updrafts along the leading edge.

This kind of storm is also known as "Wind of the Stony Lake" (Traditional Chinese:石湖風, Simplified Chinese: 石湖风) in southern China.[3]

Supercell

Supercell storms are large, severe quasi-steady-state storms which feature wind speed and direction that vary with height ("wind shear"), separate downdrafts and updrafts (i.e., precipitation is not falling through the updraft) and a strong, rotating updraft (a "mesocyclone"). These storms normally have such powerful updrafts that the top of the cloud (or anvil) can reach miles into the air and can be 15 miles (24 km) wide. These storms produce destructive tornadoes, sometimes F3 or higher, extremely large hailstones (4 inch—10 cm—diameter), straight-line winds in excess of 80 mph (130 km/h), and flash floods. In fact, most tornadoes occur from this kind of thunderstorm.[4]

Severe thunderstorm

A severe thunderstorm is a term designated to a thunderstorm that has reached a predetermined level of severity. Often this level is determined by the storm being strong enough to inflict wind or hail damage. In the United States, a storm is considered severe if winds reach over 50 knots (58 mph or 93 km/h), hail is ¾ inch (1.9 cm) diameter or larger, or if a funnel cloud or tornadoes are spotted.[5] It should be noted that even though a funnel cloud or tornado indicate the presence of a severe thunderstorm, a tornado warning would then be issued in place of a severe thunderstorm warning.

In Canada, a severe thunderstorm is defined as either having tornadoes, wind gusts of 90 km/h or greater, hail of 2 centimeters in diameter or greater, a rainfall rate greater than 50 millimeters in 1 hour or less or 75 millimeters in 3 hours or less.[6]

Severe thunderstorms can occur from any type of thunderstorm, however multicell and squall lines represent the most common forms.

Mesoscale Convective System

Multicell or squall line systems may form within a meteorologically important feature known as mesoscale convective system (MCS) stretching for hundreds of kilometres. The mesoscale convective complex is a closely related phenomenon. They are large enough to have a pronounced effect on the upper-level and surface weather pattern, and may influence forecasts over a large area. MCS systems are common in the Midwest region of the United States and the Canadian Prairies during the summer months and produce much of the region's important agricultural rainfall. [3] Prior to the discovery of the MCS phenomenon, the individual thunderstorms were thought of as independent entities, each being effectively impossible to predict. The MCS is amenable to forecasting, and a meteorologist can now predict with high accuracy the percentage of the MCS that will be affected by thunderstorms. However, the meteorologist still cannot predict exactly where each thunderstorm will occur within the MCS.

Energy

If the quantity of water that is condensed in and subsequently precipitated from a cloud is known, then the total energy of a thunderstorm can be calculated. In an average thunderstorm, the energy released amounts to about 10,000,000 kilowatt-hours (3.6×1013 joule), which is equivalent to a 20-kiloton nuclear warhead. A large, severe thunderstorm might be 10 to 100 times more energetic.[7]

Where thunderstorms occur

Thunderstorms occur throughout the world, even in the polar regions, with the greatest frequency in tropical rainforest areas, where they may occur nearly daily. Kampala and Tororo in Uganda have each been mentioned as the most thunderous places on Earth,[8] an accolade which has also been bestowed upon Bogor on Java, Indonesia or Singapore. Thunderstorms are associated with the various monsoon seasons around the globe, and they populate the rainbands of all tropical cyclones (typhoons, hurricanes, etc.) In temperate regions, they are most frequent in spring and summer, although they can occur along or ahead of cold fronts at any time of year. They may also occur within a cooler air mass following the passage of a cold front over a relatively warmer body of water. Thunderstorms are rare in polar regions due to cold surface temperatures.

The most powerful and dangerous severe thunderstorms also occur over the USA, particularly in the Midwest and the southern states. These storms can produce very large hail and powerful tornadoes. Thunderstorms are relatively uncommon along much of the West Coast of the United States,[9] but they occur with greater frequency in the inland areas, particularly the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys of California. In the Northeast, storms take on similar characteristics and patterns as the midwest, only less frequently and severely. Probably the most thunderous region outside of the Tropics is Florida. During the summer, violent thunderstorms are an almost daily occurrence over central and southern parts of the state. In more contemporary times, thunderstorms have taken on the role of a curiosity. Every spring, storm chasers head to the Great Plains of the United States and the Canadian Prairies to explore the visual and scientific aspects of storms and tornadoes.

Lightning

Lightning is an electrical discharge that occurs in a thunderstorm. It can be seen in the form of a bright streak (or bolt) from the sky. Lightning occurs when a charge is built up within a cloud. When a large enough charge is built up, a large discharge will occur and can be seen as lightning. The temperature of a lightning bolt can be hotter than the surface of the sun. Although the lightning is extremely hot, the short duration makes it not necessarily fatal. Contrary to the popular idea that lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same spot, some people have been struck by lightning over three times and skyscrapers like the Empire State Building have been struck numerous times in the same storm.[10] There are several kinds of lightning.

- In-cloud lightning is the most common. It is lightning within a cloud. Sometimes called intra-cloud or sheet lightning.

- Cloud to ground lightning is when a bolt of lightning from a cloud strikes the ground. This form poses the greatest threat to life and property.

- Ground to cloud lightning is when a lightning bolt is induced from the ground to the cloud.

- Cloud to cloud lightning is rarely seen and is when a bolt of lightning arches from one cloud to another.

- Ball lightning is extremely rare and has no known scientific explanation. It is seen in the form of a 20 to 200 centimeter ball.

- Cloud to air lightning is when lightning from a cloud hits air of a different charge.

- Dry lightning a folk misnomer which refers to a thunderstorm whose precipitation does not reach the ground.

Thunderstorms in mythology

Thunderstorms have had a lasting and powerful influence on early civilizations. Romans thought them to be battles waged by Jupiter, who hurled lightning bolts forged by Vulcan. Thunderstorms were associated with the Thunderbirds, held by Native Americans to be a servant of the Great Spirit.[11]

See also

- Cumulonimbus

- Severe thunderstorm watch

- Severe thunderstorm warning

- Tornado watch

- Tornado warning

- Supercell

References

- ^ "Weather Glossary - T". National Weather Service. 21 April 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Components of Multicell Lines". Weather World 2010 Project. University of Illinois. October 4 1999. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Squall lines and "Shi Hu Feng" - what you want to know about the violent squalls hitting Hong Kong on [[9 May]] [[2005]]". Hong Kong Observatory. 17 June 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Supercell Thunderstorms". Weather World 2010 Project. University of Illinois. October 4 1999. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Weather Glossary - S". National Weather Service. 2005-04-21. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.on.ec.gc.ca/severe-weather/summerwx_factsheet_e.html

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica article on thunderstorms

- ^ "How many thunderstorms occur each year?". Thunderstorms. Sky Fire Productions. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "National Severe Local Storms Operations Plan - Chapter 2" (PDF). Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "Lightning really does hit more than twice,", NASA, January 14, 2003

- ^ "A Haudenosaunee Pantheon "

Bibliography

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

- Burgess, D.W., R. J. Donaldson Jr., and P. R. Desrochers, 1993: Tornado detection and warning by radar. The Tornado: Its Structure, Dynamics, Prediction, and Hazards, Geophys. Monogr., No. 79, American Geophysical Union, 203–221.

- Corfidi, S. F., 1998: Forecasting MCS mode and motion. Preprints 19th Conf. on Severe Local Storms, American Meteorological Society, Minneapolis, Minnesota, pp. 626-629.

- Davies, J.M., 2004: Estimations of CIN and LFC associated with tornadic and nontornadic supercells. Wea. Forecasting, 19, 714-726.

- _____, and R.H. Johns, 1993: Some wind and instability parameters associated with strong and violent tornadoes. Part I: Helicity and mean shear magnitudes. The Tornado: Its Structure, Dynamics, Prediction, and Hazards (C. Church et al., Eds.), Geophysical Monograph 79, American Geophysical Union, 573-582.

- David, C.L. 1973: An objective of estimating the probability of severe thunderstorms. Preprint Eight conference of Severe Local Storms. Denver, Colorado, American Meteorological Society, 223-225.

- Doswell, C.A., III, D. V. Baker, and C. A. Liles, 2002: Recognition of negative factors for severe weather potential: A case study. Wea. Forecasting, 17, 937–954.

- ______, S.J. Weiss and R.H. Johns (1993): Tornado forecasting: A review. The Tornado: Its Structure, Dynamics, Prediction, and Hazards (C. Church et al., Eds), Geophys. Monogr. No. 79, American Geophysical Union, 557-571.

- Evans, Jeffry S.: Examination of Derecho Environments Using Proximity Soundings. [4]

- J.V. Iribarne and W.L. Godson, Atmospheric Thermodynamics, published by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 1973, 222 pages

- Johns, R. H., J. M. Davies, and P. W. Leftwich, 1993: Some wind and instability parameters associated with strong and violent tornadoes. Part II: Variations in the combinations of wind and instability parameters. The Tornado: Its Structure, Dynamics, Prediction and Hazards, Geophys. Mongr., No. 79, American Geophysical Union, 583–590.

- M K Yau and R.R. Rogers, Short Course in Cloud Physics, Third Edition, published by Butterworth-Heinemann, January 1, 1989, 304 pages. EAN 9780750632157 ISBN 0-7506-3215-1