Operation Camargue

| Operation Camargue | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First Indochina War | |||||||

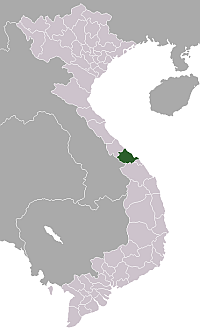

Thua Thien-Hue Province | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Leblanc | Tran Quy Ha[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~10,000[2] | One weak infantry regiment[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

17 dead, 100 wounded[4][5] |

182-200 dead, 600-1200 wounded, 387-900 prisoners[2][4][5] | ||||||

Opération Camargue, one of the largest operations by the French Far East Expeditionary Corps and Vietnamese National Army, took place from July 28 until August 10 1953. French armored platoons, airborne units and troops delivered by landing craft to the coast of central Annam, modern day Vietnam, attempted to sweep forces of the communist Viet-Minh from the critical Road One. The first landings took place in the early morning on July 28, and proceeded in reaching the first objectives, an inland canal, without major incident. A secondary phase of mopping-up operations began in a "labyrinth of tiny villages" where French armored forces suffered a series of ambushes.[6] Reinforced by paratroopers, the French and their Vietnamese allies tightened a net around the defending Viet-Minh, however delays in the movement of French forces left gaps through which the majority of the Viet-Minh guerillas, and much of the arm caches the operation was expected to seize, escaped. For the French, this validated the claim that it was impossible to operate tight ensnaring operations in Vietnam's jungle, due to the slow movement of their troops, and a foreknowledge of the enemy which was difficult to prevent.

With the French forces withdrawn from the operation by late summer, 1953, Viet-Minh Regiment 95 began to re-infiltrate Road One and resumed ambushes of French convoys,as well as retrieve weapons caches missed by the French forces. Regiment 95 occupied the area for the remainder of the First Indochina War and were still operating there as late as 1962 against the South Vietnamese Army during the Second Indochina, or Vietnam War.

Background

The First Indochina War had raged since December 19, 1946, and had, since 1949, evolved into a conventional war thanks to aid from Communist China to the north. Subsequently, the French strategy of occupying small, poorly defended outposts throughout Indochina, particularly along the Vietnamese-Chinese border, was failing. Thanks to the benefit of terrain and of the border with China, the Viet-Minh had succeeded in turning a "clandestine guerrilla movement into a powerful conventional army,"[7] something which had never been encountered by the western world previously.[8] By December 1952, with the battle of Na San complete, the French felt that their new strategy of strong ground bases, a versatile French Air Force and a model based on the British Burma campaign would bring victory over the Viet-Minh insurgents. Two months previously, the fighting that had originally remained around the Red River Delta had moved into the Thai Highlands, and at Na San this Viet-Minh attack had been defeated.[9] The Viet-Minh, however, remained unbeatable in the highland regions of Vietnam,[10] and the French "could not offset the fundamental disadvantages of a roadbound army facing a hill and forest army in a country which had few roads but a great many hills and forests."[11] General Henri Navarre arrived to take command of the French forces in May 1953, replacing General Raoul Salan. Navarre spoke of a new offensive spirit in Indochina, and the media quickly took Operation Carmargue to be a "practical realization" of that.[2]

Prelude to the battle

Road One, also referred to as Route Coloniale One or RC1, had been the "main north-south artery" along the coastline of North Vietnam since the outbreak of violence in 1949. Communications and convoys along these lines suffered from regular attacks by Viet-Minh irregulars,[12] despite efforts by the French during 1952 in Operation Sauterelle.[13] The Viet-Mind paramilitary forces around Road One originated mainly from a region of fortified villages dispersed along sand dunes and salt marshes between Hué to the south,[14] and Quang-Tri to the north.[15] French forces had suffered from Viet-Minh ambushes, an attack that the latter had become very proficient at throughout the war, most notably in the annihilation of Group Mobilés 42 and 100.[16] The roads in Vietnam were almost all closed during the night and "abandoned to the enemy."[12] 398 armored vehicles were destroyed by enemy action from 1952 until 1954, 84% from mines and booby traps.[17] These methods were common in Viet-Minh, and later Viet-Cong ambushes, where the lead vehicle and the last vehicle would both be destroyed by remote mines, trapping the convoy on the road after it had been stopped by a fallen tree or pile of boulders.[18] Caltraps, mines and the steep cliff faces naturally found at the road side aided in funneling the target convoy into a small area, where machine guns, mortars and recoilless rifles are trained.[17]

These tactics were employed by Viet-Minh Regiment 95, inflicting severe losses on the French forces passing through Road One, which led to the road being called la rue sans joie or Street Without Joy by the French forces. Regiment 95 was part of Viet-Minh Division 325 along with regiments 18 and 101, together commanded by General Tran Quy Ha. The division had been formed in 1951 from pre-existing units in Thua Thien just north of Road One, and became operational in the summer of 1952.[1] In 1953, the French command had "sufficient reserves" at hand to begin clearing the Viet-Minh back from Road One with Operation Camargue, named for the swamp-filled coastline to the west of Marseilles, France.[15] Although the difficult terrain was an advantage for the one Viet-Mind regiment station around the Street Without Joy, the French had marshalled thirty battalions, two armored regiments and two artillery regiments in one of the largest operations of the conflict.[3]

The terrain, however, was to prove decisive.[4] From a straight 100 meter deep coastline of "hard sand" the French landed forces were to advance through a series of dunes up to 60 feet high and indispersed with precipices, ditches and a handful of small villages.[3] Beyond this was 800 meters of pagodas and temples, which Bernard Fall describes as having excellent defensive potential. Beyond these temples was Road One itself with a series of closely packed and fortified villages, including Tan An, My Thuy, Van Trinh and Lai-Ha.[19] This network of villages and hedgerows made both ground and air surveillance difficult. Across from Road One the villages continued amid an area of quicksand, swamps and bogs which would stop all but a few of the vehicles at the disposal of the French. There were a series of roads, however, most were mined or damaged. Throughout the area, the civilian population had also remained and provided a further complication for the French High Command.[20]

French order of battle

...ten infantry regiments, two airborne battalions, the bulk of three armored regiments, one squadron of armored launches and one armored train, four artillery battalions, thirty four transport aircraft, six reconnaissance aircraft and twenty two fighter bombers, and about twelve Navy ships, including three LST's—this force was not inferior in size to come of those used in landing operations in World War II in the pacific.

– Bernard Fall, Street Without Joy, 1961. Page 144.

The French divided their forces into four groups, A through D. Group A consisted of Mobilé Group 14, which contained 3d Amphibious Group, 2d Marine Commando, 2d Battalion 1st Colonial Parachute Regiment and 3d Vietnamese Parachute Battalion. It was to land on the beach in line with the center of Road One. Meanwhile, Group B was to advance over land from the west of the north-east facing beach. This group consisted of Mobilé Group Central Vietnam's 6th Moroccan Spahis, 2d Amphibious Group, a tank platoon from 1st Foreign Legion and two infantry companies from the Quang-Tri military base. Group C was to advance from the south-west into the back of Van Trinh through the swamps, and consisted of the 9th Moroccan Tabor, 27th Vietnamese Infantry Battalion, 2nd Battalion of the 4th Moroccan Rifle Regiment, 1 Commando, a tank platoon of the Moroccan Colonials, an Armored Patrol Boat Platoon and an LCM Platoon. Group D consisted of 3d Battalion of the 3d Algerian Rifles, the 7th Amphibious Group and a Commando group, and was to land at the south-east end of the beach, below Group A.[21] These forces in total formed "two amphibious forces, three land-borne groupments and one airborne force" all of which was commanded by General Leblanc.[3] This French force, vastly outnumbering the Viet-Minh regiment opposing it, was tasked with sealing the Communist forces into a tight pocket, and systematically destroying them, as well as capturing as many prisoners, arms caches and as much equipment as possible.

Securing the Street Without Joy

French landing

On July 27 1953, the French landed craft departed from their assembly points, and by 0400 on the following had begun disembarking 160 amphibious landing crafts belonging to Group A's 3d Amphibious opposite the coastline. By 0600 these vehicles had landed on the beach and proceeded to occupy sand ridges overlooking the dunes beyond. Proceeding into the dunes, the vehicles of 3d Amphibious became stuck in the sand, and in the meantime other regular infantry elements of Group A were experiencing more difficulties in the sea, taking two extra hours to reach the beach. Thus unsupported, elements of 3d Amphibious that either disembarked floundering vehicles or were pushed, managed to escape the dunes and advance between Tan An and My Thuy.[22] The Amphibious vehicles used by the French were the Second World War-era 29-C cargo carriers, nicknamed the 'Crab' or 'Crabe' and LVT 4 or 4As, known as the 'Alligator'.[23] The latter was armed with two .30 calibre and two .50 calibre Browning machine guns and an M20 recoiless rifle.[24] While the Alligators were heavily armored and well suited to the water, they struggled on land. In contrast, the Crab had difficulty in water and its large size presented too greater a target on land, however it was lighter and more maneuverable,[25] except in paddy fields where its suspension became clogged with vegetation.[23]

While Group A's forward elements were breaching the dune barrier hitherto unopposed, Group B had seen two of her battalions cross the Van Trinh Canal. These units succeeded in sealing off Regiment 95s north escape route by 0745 when they made visual contact with the 'Crabs' and 'Alligators' of Group A.[22] The 6th Moroccan Spahis also succeeded in reaching the canal by 0830, having had difficulty crossing the swamps on the landward side with their M24 Chaffee tanks. No French units, as yet, had made any major contact with the Viet-Minh. A minor shootout had taken place on the southern edge of Group B's advance when an Algerian company exchanged fire with 20-30 Viet-Minh and suffered the first French fatality.[26] Simultaneously, Group C had advanced into the centre of the area of operation, and executed "the most complicated maneuver of the operation." This involved crossing Road One and sealing off the land side of the operational area, and was completed by 0830.[26]

Group D, finally, was tasked with advancing south from its landing point to close off an escape route that ran between the sea and an inland lagoon towards the city of Hué. Landing at 0430, the group made quick progress through the beach and dunes, secured the small city of Thé Chi Dong and hit the north coast of the lagoon by 0530, thereby sealing off that escape route with no enemy contact. The final act of sealing the noose was to move some of the French Navy vessels north to the Vietnamese villages of Ba-Lang and An-Hoi where any attempt by Regiment 95 to flee by sea would have taken place.[6]

Tightening the loop

With the landings and the encirclement of Regiment 95 complete and the net deemed secure, the French forces began the second phase of the operation and began to sweep through the area for the encircled Viet-Minh. Each French Group began to move through the villages around Road One in an attempt to locate the Viet-Minh forces. Group B, which was lined up along the canal - the jump-off point for the second phase of the operation - moved to sweep the northern villages while Group C did the same further south. The method of searching each village was to seal it off entirely with encircling troops, and then inspect it with a heavily armed unit of minesweepers and K-9 teams. Men of military age were arrested and screened by intelligence officers.[6] This process was time-consuming, and by 110 Group B had traveled 7 kilometers through the network of villages with no results or resistance. At this time, the 6th Moroccan Spahis entered the village of Dong-Qué with their M-24 tanks and the support of the 1st Battalion of the Moroccan Rifles and the artillery of Colonel Piroth (later commander of the artillery at the battle of Dien Bien Phu) and his 69th African Artillery Regiment.[27]

The Moroccan infantry took the lead, and the French commanders sealed themselves in their tank turrets and advanced behind. Viet-Minh forces, which were waiting in ambush, fired almost the same instant as the lead Moroccan units who noticed their presence. The Moroccan forces spread out into the surrounding rice paddies, and the bazookas of the Viet-Minh missed the French tanks. The French commander called in Piroth's artillery and Dong-Qué "disintegrated under the impact of their high-angle fire,"< particularly when a French shell found the Viet-Minh ammunition depot.ref name=fall162>Fall, p. 162.</ref> As the French tanks approached, the Viet-Minh drove the civilians out to clog up the entrance to the village, however as the Viet-Minh retreated they were spotted through the civilians by the Moroccan infantry and killed by 1300. During this battle, however, the majority of Regiment 95 that had been elsewhere managed to escape towards the southern end of the French encirclement.[28] Leblanc had realized the intentions of Regiment 95's commander, and had requested one of the two reserve paratroop units to be deployed at the border between the network of temples and the dune-filled area in front of where Group D had originally landed. This paratroop unit, 2d Battalion of the 1st Colonial Parachute Regiment, began to advance towards the canal at 1045, fifteen minutes before Group B entered Dong-Qué.

Group C's 9th Tabor had also, like the M-24's of Group B, struggled through the marshes during the first phase of the operation, and were late in arriving at the jumping-off point for phase two, the canal. At 0845, Moroccan units of Group C were investigating the village of Phu-An on the opposite side of the lagoon from Group D's landing area, when they came under heavy fire. Despite being nearer to Group D, the engaged units radioed their immediate commanders back in Group C, who were by now some distance away, further inland.[29] This delay, coupled with the failure of many of the units SCR300 radios,meant that these advance elements of Group C failed to get through until 0910. At 0940, the commander of Group C called up various reinforcements from Huém including two companies of Vietnamese trainee NCOs and five infantry companies, two of which came via landing craft and did not reach the beleaguered elements of Group C until 1800, half an hour after the Moroccans had finally counterattacked and occupied Phu-An.[30] A second parachute battalion, the Parachute Chasseurs of II/1 RCP,[14][29] had also been requested to drop and supported the advanced elements of Group C, however these were also delayed and did not drop until 1650 despite being ordered for 1400, and also failed to assemble before the Moroccans themselves occupied Phu-An.[31] With the final capture of Phu-An, the extreme southern tip of the encirclement, the pincer movement was complete.[32]

Escape of Regiment 95

By 1730, with Phu-An captured, all French reserves now committed, and one half of the pocket fully swept by Groups B and A at the northern end of the battlefield, the French appeared to have gained the upper hand. There had now, however, been the expected windfall of arms caches and prisoners.[32] The time taken to capture Phu-An, and the fact that the paratroop reinforcements had been both delayed in deploying and scattered by the winds, had left a gap between Phu-An and the southern edge of the lagoon. This gap of 12 kilometers was eventually covered by only four French battalions, leaving gaps through which the Viet-Ming could escape. Crabs and Alligators were stationed on, or in some cases in, the canal network, and French infantry were scattered across the edge of the pocket throughout that night in order to detect escaping Viet-Minh. However, despite the occasional shot, flare and searchlight, no Viet-Minh were detected.[33]

On the morning of July 29 1953, the French forces continued to advance into the remaining nine square miles pocket, encountering neither Viet-Minh nor civilian.[2] Groups A, B and D reached the edge of the canal opposite Group C by 1300, having retrieved a small number of suspected Viet-Minh and a "few weapons".[34] At this time, however, a Morane aircraft detected the movement of elements of Regiment 95 towards An-Hoi on the extreme northern corner of the operational area, outside of the pocket. The French carried out a raid on An-Hoi by commando groups and elements of Group A, which took place at 1500 and returned with suspected Viet-Minh by 1800.[34] The French then undertook a methodical house-to-house search of the entire area, sweeping each village, and the surrounding paddy fields and jungle, risking encounter with Viet-Minh caltrops. Meanwhile, 2d and 3d Amphibious used their Crabs and Alligators to herd prisoners towards Trung-An for interrogation. By the end of July 29, with resistance to the French forces having ceased, a general withdrawal of paratroopers, amphibious groups and marines began.[35][5]

Aftermath

Rebuilding and reaction

After the departure of all but regular French infantry, efforts to make the area suitable for permanent occupation by French forces and French-friendly civilians began. This involved the rebuilding of road and rail links (a rail line ran alongside Road One),[19] the repairing of infrastructure, demining, the installation of new Vietnamese government administrators,[35] and the provision of "everything from rice to anti-malaria tablets."[36] Over 24 villages were placed under the authority of the Vietnamese government, and Regiment 95 had been driven from the area.[37] In comparison to Fall, Vietnamese General Lam Quang Thi states in his memoirs that Operation Camargue was "one of the most successful French military operations during the Indochina war" in the area of Road One.[38]

...although the operation does not appear to have been successful in all its objectives, 600 Viet-Minh soldiers were killed or wounded, and 900 others were captured. Important stocks of paddy were found, but the number of arms captured was not as great as expected; it is thought that: the Viet-Minh soldiers, on finding themselves surrounded, threw their weapons into the rice fields and swamps.

- A French Spokesperson, quoted in: Viet Nam Hopes Of Independence Coming Talks In Paris, The Times, Saturday August 1 1953 page 5 column D. Issue: 52689

Newspapers stated that the operation had been a "total success, demonstrating once more the new aggressiveness and mobility" of the French forces.[36][37] However in the days following the end of the fighting, newspapers began to publish stories on the failure to capture the large numbers of Viet-Minh as had been expected, however England's The Times still published casualty figures of 1,550 for the Viet-Minh, 200 of which killed.[5] This estimate was altered by the French the next day to 600 killed or wounded and 900 captured, and it was suggested that the operation did "not appear to have been successful."[39] In contrast to these figures, Bernard Fall records 182 Viet-Minh casualties and 387 prisoners. He also notes that "51 rifles, eight sub-machine guns, two mortars, and five BARs" were captured. Of the prisoners, however, it is not recorded how many were confirmed to be members of Regiment 95. Both Fall and the newspapers published in the days following the official termination of the operation on August 10 1953, give French casualties as 17 dead and 100 wounded.[4][37]

Fall goes on to record that the "major defect" of Operation Camargue was that the French had nothing like the numerical superiority to encircle a force in the terrain around Road One, 15:1 as opposed to the 20:1 or 25:1 that he believed required. He states that the slow French progress (around 1,500 yards an hour)[37] and the large distances each unit had to guard from Viet-Minh infiltration meant that the Viet-Minh could easily escape the net.[4] He also states that Viet-Minh intelligence were always aware of French movements, as the size of French units and the complex technology involved in the operation gave its presence and intentions away almost immediately, whereas in contrast the simpler Viet-Minh operations were far more difficult to detect.[40]

Road One and Regiment 95

Regiment 95 survived Operation Camargue and resumed ambushes in 1954, as well as assaulting a Vietnamese garrison near Hué. The regiment remained in the area, taking part in General Giaps 1954 campaign season, until Vietnam was split into North and South Vietnam by the cease-fire, whereupon it infiltrated back to the north along Road One during broad daylight.[41] The regiment returned in 1962 to resume ambushes of the South Vietnamese Army in 1962.[40]

Notes

- ^ a b Windrow, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d French Clean-Up Of Viet-Minh Area New Offensive Spirit In Indo-China, The Times, Thursday July 30 1953 page 5, column B. Issue: 52687

- ^ a b c d Fall, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e Fall, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d French Blow At Viet-Minh Some Rebels Escape The Net, The Times, Friday July 31 1953 page 7 column E, Issue: 52688

- ^ a b c Fall, p. 151.

- ^ Windrow, p. 41.

- ^ Windrow, p. 42

- ^ Windrow, p. 56

- ^ Windrow, p. 121.

- ^ Windrow, p. 129.

- ^ a b Windrow, p. 102.

- ^ Dunstan p. 9

- ^ a b Windrow, p. 236.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 144.

- ^ Fall, p. 242.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 354.

- ^ Dunstan, p. 15

- ^ a b Fall, p. 146.

- ^ Fall, p. 147.

- ^ Fall, p. 144-146.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 149.

- ^ a b Dunstan, p. 20

- ^ Dunstan, p. 21.

- ^ Fall, p. 148.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 150.

- ^ Windrow, p. 309.

- ^ Fall, p. 162.

- ^ a b Windrow, The French Infochina War, 1946-1954 p. 44.

- ^ Fall, p. 164.

- ^ Fall, p. 165.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 166.

- ^ Fall, p. 167.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 168.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 169.

- ^ a b Fall, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d Chaliand, p. 132.

- ^ Lam Quang Thi p. 337.

- ^ Viet Nam Hopes Of Independence Coming Talks In Paris, The Times, Saturday August 1 1953 page 5 column D. Issue: 52689

- ^ a b Fall, p. 172

- ^ Windrow, p 262.

References

Printed Sources:

- Chaliand, Gérard Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology from the Long March to Afghanistan, California, 1982 ISBN 0520044436

- Dunsten, Simon Vietnam Tracks: Armor in Battle 1945-75, Osprey Publishing, 2004 ISBN 1841768332

- Fall, Barnard Street Without Joy, Stackpole Books, 1994 ISBN 0811717003

- Quang Thi Lam The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon, University of North Texas, 2002 ISBN 1574411438

- Windrow, Martin The French Indochina War, 1946-1954, Osprey, 1998 ISBN 1855327899

- Windrow, Martin The Last Valley. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004 ISBN 0306813866

Websites:

- The Times Issues 52687, 52688 and 52689 all retrieved from The Times Digital Archive via The University of Exeter on January 9 2007