Id, ego and superego

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

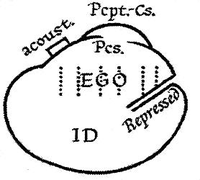

Id, ego, and super-ego are the three parts of the 'psychic apparatus' defined in Freud's structural model of the psyche; they are the three 'structures' in terms of whose activity and interaction mental life is described.

The actual terms 'id', 'ego' and 'super-ego' are not Freud's own, but are latinisations originating from his translator James Strachey. Freud himself wrote of 'das Es', 'das Ich', and 'das Über-Ich' -- respectively, 'the It', 'the I', and the 'Over-I' (or 'Upper-I').

The concepts themselves arose at a late stage in the development of Freud's thought: the 'structural model' was first discussed in his 1920 essay "Beyond the Pleasure Principle" and was formalized and elaborated upon three years later in his "The Ego and the Id". While much of Freud's theory of psychoanalysis has fallen out of favor in the scientific and medical communities[1], the id-ego-superego construct gained such notoriety in Freud's lifetime that it remains to this day a common way for laypersons to consider or "understand" the human subconscious.

Id

The term id (inner desire) is a Latinised derivation from Groddeck's das Es,[2] and translates into English as strictly "it". It stands in direct opposition to the super-ego. It is dominated by the pleasure principle.

The mind of a newborn child is regarded as being completely "id-ridden", in the sense that it is a mass of instinctive drives and impulses, and demands immediate satisfaction. This view equates a newborn child with an id-ridden individual—often humorously—with this analogy: an alimentary tract with no sense of responsibility at either end.

The id is responsible for our basic drives such as food, sex, and aggressive impulses. It is amoral and egocentric, ruled by the pleasure–pain principle; it is without a sense of time, completely illogical, primarily sexual, infantile in its emotional development, and will not take "no" for an answer. It is regarded as the reservoir of the libido or "love energy".

Freud divided the id's drives and instincts into two categories: life and death instincts - the latter not so usually regarded because Freud thought of it later in his lifetime. Life instincts are those that are crucial to pleasurable survival, such as eating and copulation. Death instincts, as stated by Freud, are our unconscious wish to die, as death puts an end to the everyday struggles for happiness and survival. Freud noticed the death instinct in our desire for peace and attempts to escape reality through fiction, media, and substances such as alcohol and drugs. It also indirectly represents itself through aggression.

Ego

In Freud's theory, the ego mediates among the id, the super-ego and the external world. Its task is to find a balance between primitive drives and reality [the Ego devoid of morality at this level] while satisfying the id and super-ego. Its main concern is with the individual's safety and allows some of the id's desires to be expressed, but only when consequences of these actions are marginal. Ego defense mechanisms are often used by the ego when id behavior conflicts with reality and either society's morals, norms, and taboos or the individual's expectations as a result of the internalization of these morals, norms, and their taboos.

The word ego is taken directly from Latin, where it is the nominative of the first person singular personal pronoun and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. The Latin term ego is used in English to translate Freud's German term Das Ich, which literally means "the I".

In modern-day society, ego has many meanings. It could mean one’s self-esteem; an inflated sense of self-worth; or in philosophical terms, one’s self. However, according to Freud, the ego is the part of the mind which contains the consciousness. Originally, Freud had associated the word ego to meaning a sense of self; however, he later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality-testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory.

In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted to be half in the consciousness, while a quarter is in the preconscious and the other quarter lies in the unconscious.

The ego is the mediator between the id and the super-ego, trying to ensure that the needs of both the id and the super-ego are met. It is said to operate on a reality principle, meaning it deals with the id and the super-ego; allowing them to express their desires, drives and morals in realistic and socially appropriate ways. It is said that the ego stands for reason and caution, developing with age. Sigmund Freud had used an analogy which likened the ego to a rider and a horse; the ego being the rider while the id being the horse. The horse provides the energy and the means of obtaining the energy and information need, while the rider ultimately controls the direction it wants to go. However, due to unfavorable conditions, sometimes the horse makes its own decisions over the rocky terrain.

When the ego is personified, it is like a slave to three harsh masters: the id, the super-ego and the external world. It has to do its best to suit all three, thus is constantly feeling hemmed by the danger of causing discontent on two other sides. It is said however, that the ego seems to be more loyal to the id, preferring to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the super-ego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority. To overcome this, this ego employs methods of defense mechanism.

Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. However, his daughter Anna Freud clarified and identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatization, splitting and substitution.

Super-ego

Freud's theory implies that the super-ego is a symbolic internalization of the father figure and cultural regulations. The super-ego tends to stand in opposition to the desires of the id because of their conflicting objectives, and its aggressiveness towards the ego. The super-ego acts as the conscience, maintaining our sense of morality and proscription from taboos. Its formation takes place during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex and is formed by an identification with and internalization of the father figure after the little boy cannot successfully hold the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration.

The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on — in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt (The Ego and the Id, 1923).

In Sigmund Freud's work Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) he also discusses the concept of a "cultural super-ego". The concept of super-ego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore form a weak super-ego, leaving them susceptible to immorality and sexual identity complications.

References

- ^ "Who’s Afraid of Sigmund Freud?"

- ^ Groddeck, G.W. (1928). "The Book of the It" Nervous and Mental Diseases Publishiing Com, New York

Further reading

- Freud, Sigmund (1910), "The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis", American Journal of Psychology 21(2), 196–218.

- Freud, Sigmund (1920), Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

- Freud, Sigmund (1923), Das Ich und das Es, Internationaler Psycho-analytischer Verlag, Leipzig, Vienna, and Zurich. English translation, The Ego and the Id, Joan Riviere (trans.), Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-analysis, London, UK, 1927. Revised for The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, James Strachey (ed.), W.W. Norton and Company, New York, NY, 1961.

- Gay, Peter (ed., 1989), The Freud Reader. W.W. Norton.

See also

People

|

|

Related topics

|

|

External links

- American Psychological Association

- Sigmund Freud and the Freud Archives

- Section 5: Freud's Structural and Topographical Model, Chapter 3: Personality Development Psychology 101.

- An introduction to psychology: Measuring the unmeasurable

- lacan dot com, Jacques Lacan in the US

- Sigmund Freud

- Sigmund Freud's theory

- Feigning Interest, a video interpretation of the id, ego and super-ego