Bullfighting

Bullfighting or tauromachy (from Greek ταυρομαχία - tauromachia, "bull-fight"), is a traditional blood sport spectacle of Spain, Portugal, some cities in southern France, and several Latin American countries. Its origin is unknown and there are several competing, opposed and inconclusive theories.

The tradition, as it is practiced today, involves professional performers, toreros (also refered to as toreadors in English), who execute various formal moves with the goal of appearing graceful and confident, while masterful over the bull itself. Such maneuvers are performed at close range, and conclude often with the death of the bull by a well-placed sword thrust as the finale. In Portugal the finale consists of a tradition called the pega, where men (forcados) try to hold the bull by its horns when it runs at them. Forcados are dressed in a traditional costume of damask or velvet, with long knit hats as worn by the campinos (bull headers) from Ribatejo.

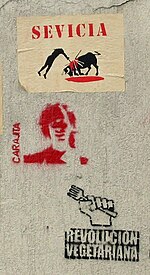

Bullfighting generates heated controversy in many areas of the world, including Spain. Supporters of bullfighting argue that it is a culturally important tradition, while most nations argue that it is a blood sport because of the suffering of the bull and horses during the bullfight.

History

Bullfighting traces its roots to prehistoric bull worship and sacrifice. The killing of the sacred bull (tauromachy) is the essential central iconic act of Mithras, which was commemorated in the mithraeum wherever Roman soldiers were stationed. Many of the oldest bullrings in Spain are located on or adjacent to the sites of temples to Mithras. [citation needed]

Bullfighting is often linked to Rome, where many human-versus-animal events were held as a warm-up for gladiatorial sports. There are also theories that it was introduced into Hispania a millennium earlier by the Emperor Claudius when he instituted a short-lived ban on gladiatorial games, as a substitute for those combats. The later theory was supported by Robert Graves. In its original form, the bull was fought from horseback using a javelin[citation needed]. (Picadors are the remnants of this tradition, but their role in the contest is now a relatively minor one limited to "preparing" the bull for the matador.) Bullfighting spread from Spain to its Central and South American colonies, and in the 19th century to France, where it developed into a distinctive form in its own right.

Bullfighting was practiced by nobility[citation needed] as a substitute and preparation for war in the manner of hunting and jousting. Religious festivities and royal weddings were celebrated by fights in the local plaza, where noblemen would ride competing for royal favor, and the populace enjoyed the excitement. In the 18th century, the Spanish introduced the practice of fighting on foot around 1726. Francisco Romero is generally regarded as having been the first to do this.

As bullfighting developed, men on foot started using capes to aid the horsemen in positioning the bulls. This type of fighting drew more attention from the crowds. Thus the modern corrida, or fight, began to take form, as riding noblemen were substituted by commoners on foot. This new style prompted the construction of dedicated bullrings, initially square, like the Plaza de Armas, and later round, to discourage the cornering of the action. The modern style of Spanish bullfighting is credited to Juan Belmonte, generally considered the greatest matador of all time. Belmonte introduced a daring and revolutionary style, in which he stayed within a few inches of the bull throughout the fight. Although extremely dangerous (Belmonte himself was gored on many occasions), his style is still seen by most matadors as the ideal to be emulated. Today, bullfighting remains similar to the way it was in 1726, when Francisco Romero, from Ronda, Spain, used the estoque, a sword, to kill the bull, and the muleta, a small cape used in the last stage of the fight.

Bullfighting has had its detractors throughout history. Pope Pius V issued a papal bull titled De Salute Gregis in November 1567 which forbade fighting of bulls and any other beasts but it was abolished eight years later by his successor, pope Gregory XIII, at the request of king Philip II.

During the 18th and 19th centuries there were several attempts to prohibit or limit bullfighting but they proved impossible and it was during these two centuries that the bullfight acquired the form it has today. During the Franco dictatorship bullfights were supported by the state as something genuinely Spanish so that bullfights became associated with the regime and, for this reason, many thought they would decline after the transition to democracy but this did not happen. During this time the socialdemocrat governments, particularly the current government of Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, have generally been more opposed to bullfighting, prohibiting children under 14 from attending and limiting or prohibiting the broadcast of bullfights on national TV. During the current (2008) social-democrat administration most bullfights are broadcast on regional TV stations. However, given the PSOE's strong political support in Andalusia, where the popularity of bullfighting remains strong, sentiments within the social-democratic government are divided regarding bullfighting.[citation needed]

The Spanish royal family is also divided on the issue, from queen Sophia who does not hide her dislike for bullfights [1], to king Juan Carlos who occasionally presides a bullfight from the royal box as part of his official duties [2] [3] [4], to their daughter princess Elena who is well known for her liking of bullfights and who often accompanies the king in the presiding box or attends privately in the general seating [5].

Styles of bullfighting

Originally, there were at least five distinct regional styles of bullfighting practiced in southwestern Europe: Andalusia, Aragon-Navarre, Alentejo, Camargue, Aquitaine. Over time, these have evolved more or less into standardized national forms mentioned below. The "classic" style of bullfight, in which the bull is killed, is the form practiced in Spain, Southern France and many Latin American countries.

Spanish-style bullfighting

Spanish-style bullfighting is called corrida de toros (literally running of bulls) or fiesta brava (the ferocious festival). In traditional corrida, three toreros, or matadores, each fight two bulls, each of which is at least four years old and weighs 460–600 kg. Each matador has six assistants — two picadores ("lancers") mounted on horseback, three banderilleros ("flagmen"), and a mozo de espada ("sword page"). Collectively they comprise a cuadrilla ("entourage").

The modern corrida is highly ritualized, with three distinct stages or tercios, the start of each being announced by a trumpet sound. The participants first enter the arena in a parade to salute the presiding dignitary, accompanied by band music. Torero costumes are inspired by 18th century Andalusian clothing, and matadores are easily distinguished by their spectacular "suit of lights" (traje de luces).

Next, the bull enters the ring to be tested for ferocity by the matador and banderilleros with the magenta and gold capote ("dress cape").

In the first stage, the tercio de varas ("the lancing third"), the matador first confronts the bull and observes his behavior in an initial section called suerte de capote. Next, a picador enters the arena on horseback armed with a vara ("lance"). To protect the horse from the bull's horns, the horse is surrounded by a peto — a protective cover. Prior to 1909, the horse did not wear any protection, and the bull could literally disembowel the horse during this stage.

At this point, the picador stabs a mound of muscle on the bull's neck, leading to the animal's first loss of blood. The manner in which the bull charges the horse provides important clues to the matador on which side the bull is favoring. If the picador does his job well, the bull will hold its head and horns lower during the following stages of the fight. This makes it slightly less dangerous while enabling the matador to perform the elegant passes of modern bullfighting.

In the next stage, the tercio de banderillas ("the third of flags"), the three banderilleros each attempt to plant two razor sharp barbed sticks (called banderillas) on the bull's flanks, ideally as close as possible to the wound where the picador drew first blood. These further weaken the enormous ridges of neck and shoulder muscle through loss of blood, while also frequently spurring the bull into making more ferocious charges.

In the final stage, the tercio de muerte ("the third of death"), the matador re-enters the ring alone with a small red cape (muleta) and a sword. It is a common misconception that the color red is supposed to anger the bull, despite the fact bulls are colorblind (the real reason that a red colored cape is used is that any blood stains on it will be less noticeable). He uses his cape to attract the bull in a series of passes, both demonstrating his control over it and risking his life by getting especially close to it. The faena ("work") is the entire performance with the muleta, which is usually broken down into "tandas" or "series". The faena ends with a final series of passes in which the matador with a muleta attempts to maneuver the bull into a position to stab it between the shoulder blades and through the aorta or heart. The act of thrusting the sword is called an estocada.

Occasionally, if the bull has fought bravely, and by petition of the public or the matador, the president of the plaza may grant the bull an indulto. This is when the bull’s life is spared and allowed to leave the ring alive and return to the ranch where it came from. However, few bulls survive the trip back to the ranch. With no veterinarian services at the plaza, most bulls die either while awaiting transportation or days later after arriving at their original ranch. Death is due to dehydration, infection of the wounds and loss of blood sustained during the fight.[1]

Recortes

Etching and aquatint

The Basque-Navarre style of bullfighting has been far less popular than traditional Spanish bullfighting. There has been a recent resurgence of recourtes in Spain where they are sometimes shown on TV.

This style was common in the early 19th century. Etchings by painter Francisco de Goya depict these events.

Recourtes differs from a corrida in the following ways:

- The bull is not physically injured. Drawing blood is rare and the bull returns to his pen at the end of the performance.

- The men are dressed in common street clothes and not in traditional bullfighting dress.

- Acrobatics are performed without the use of capes or other props. Performers attempt to evade the bull solely through the swiftness of their movements.

- Rituals are less strict so the men have freedom to perform stunts as they please.

- Men work in teams but with less role distinction than in a corrida.

- Teams compete for points awarded by a jury.

Animal rights groups such as PETA object to recourtes, however many people find recourtes less objectionable than traditional bullfighting since the bull survives the ordeal. Since horses are not used, and performers are not professionals, recourtes are less costly to produce.

Portuguese

Most Portuguese bullfights are held in two phases: the spectacle of the cavaleiro, and the pega. In the cavaleiro, a horseman on a Portuguese Lusitano horse (specially trained for the fights) fights the bull from horseback. The purpose of this fight is to stab three or four bandeirilhas (small javelins) in the back of the bull.

In the second stage, called the pega ("holding"), the forcados, a group of eight men, challenge the bull directly without any protection or weapon of defense. The front man provokes the bull into a charge to perform a pega de cara or pega de caras (face grab). The front man secures the animal's head and is quickly aided by his fellows who surround and secure the animal until he is subdued. [2]

The bull is not killed in the ring and, at the end of the corrida, leading oxen are let into the arena and two campinos on foot herd the bull along them back to its pen. The bull is usually killed, away from the audience's sight, by a professional butcher. It can happen that some bulls, after an exceptional performance, are healed, released to pasture until their end days and used for breeding.

French

Since the 19th century Spanish-style corridas have been increasingly popular in Southern France where they enjoy legal protection in areas where there is an uninterrupted tradition of such bull fights, particularly during holidays such as Whitsun or Easter. Among France's most important venues for bullfighting are the ancient Roman arenas of Nîmes and Arles, although there are bull rings across the South from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coasts.

A more indigenous genre of bullfighting is widely common in the Provence and Languedoc areas, and is known alternately as "course libre" or "course camarguaise". This is a bloodless spectacle (for the bulls) in which the objective is to snatch a rosette from the head of a young bull. The participants, or raseteurs, begin training in their early teens against young bulls from the Camargue region of Provence before graduating to regular contests held principally in Arles and Nîmes but also in other Provençal and Languedoc towns and villages. Before the course, an encierro — a "running" of the bulls in the streets — takes place, in which young men compete to outrun the charging bulls. The course itself takes place in a small (often portable) arena erected in a town square. For a period of about 15–20 minutes, the raseteurs compete to snatch rosettes (cocarde) tied between the bulls' horns. They don't take the rosette with their bare hands but with a claw-shaped metal instrument called a raset in their hands, hence their name. Afterwards, the bulls are herded back to their pen by gardians (Camarguais cowboys) in a bandido, amidst a great deal of ceremony. The star of these spectacles are the bulls, who get top billing and stand to gain fame and statues in their honor, and lucrative product endorsement contracts. [3]

Another type of French 'bullfighting' is the course landaise style, in which cows are used instead of bulls. This is a competition between teams named cuadrillas, which belong to certain breeding estates. A cuadrilla is made up of a teneur de corde, an entraîneur, a sauteur, and six écarteurs. The cows are brought to the arena in boxes and then taken out in order. Teneur de corde controls the dangling rope attached to cow's horns and the entraîneur positions the cow to face and attack the player. The écarteurs will try to dodge around the cow in the latest instance possible and the sauteur will leap over it. Each team aims to complete a set of at least one hundred dodges and eight leaps. This is the main scheme of the "classic" form, the course landaise formelle. However, different rules may be applied in some competitions. For example, competitions for Coupe Jeannot Lafittau are arranged with cows without ropes.

Freestyle bullfighting

Freestyle bullfighting is a style of bullfighting developed in American rodeo. The style was developed by the rodeo clowns who protect bull riders from being trampled or gored by an angry bull. Freestyle bullfighting is a 70-second competition in which the bullfighter (rodeo clown) avoids the bull by means of dodging, jumping and use of a barrel. Competitions are organized in the US as the World Bullfighting Championship (WBC) and the Dickies National Bullfighting Championship under auspices of the Professional Bull Riders (PBR).

Hazards

Spanish-style bullfighting is normally fatal for the bull, and it is very dangerous for the matador. (Picadors and banderilleros are sometimes gored, but this is not common. They are paid less and noticed less, because their job takes less skill and, in particular, less courage.) The suertes with the capote are risky, but it is the faena that is supremely dangerous, in particular the estocada. A matador of classical style—notably, Manolete—is trained to divert the bull with the muleta but always come close to the right horn as he makes the fatal sword-thrust between the clavicles and through the aorta. At this moment, the danger is the greatest. A lesser matador can run off to one side and stab the bull in the lungs—and may even achieve a quick kill—but it will not be a clean kill, because he will have avoided the difficult target, and the mortal risk, of the classical technique. Such a matador will often be booed.

Some matadors, notably Juan Belmonte, have been gored many times: according to Ernest Hemingway, Belmonte's legs were marred by many ugly scars. A special type of surgeon has developed, in Spain and elsewhere, to treat cornadas, or horn-wounds: they are well paid and well respected. The bullring normally has an infirmary with an operating room, reserved for the immediate treatment of matadors with cornadas.

The bullring has a chapel where a matador can pray before the corrida, and where a priest can be found in case an emergency sacrament is needed. The most relevant sacrament is now called "Anointing of the Sick"; it was formerly known as "Extreme Unction", or the "Last Rites". It is administered to Catholics who are in seriously ill or injured and in danger of death in the near future. Since bullfighting is a tradition in Spain and other Catholic countries, it is traditionally assumed that a matador is a Catholic. The traditional procedures do not allow for other possibilities, but special arrangements could be made by a matador who was willing to take the trouble—and to acknowledge his own mortality.

Although the course camarguaise does not end in the death of the bull, it is at least as dangerous to the human contestants as a corrida. At one point it resulted in so many fatalities that the French government tried to ban it, but had to back down in the face of local opposition. The bulls themselves are generally fairly small, much less imposing than the adult bulls employed in the corrida. Nonetheless, the bulls remain dangerous due to their mobility and vertically formed horns. Participants and spectators share the risk; it is not unknown for angry bulls to smash their way through barriers and charge the surrounding crowd of spectators. The course landaise is not seen as a dangerous sport by many, but écarteur Jean-Pierre Rachou died in 2003 when a bull's horn tore his femoral artery.

Cultural aspects of bullfighting

Many supporters of bullfighting regard it as a deeply ingrained, integral part of their national cultures. The aesthetic of bullfighting is based on the interaction of the man and the bull. Rather than a competitive sport, the bullfight is more of a ritual which is judged by aficionados (bullfighting fans) based on artistic impression and command. Ernest Hemingway said of it in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon: "Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter's honour." Bullfighting is seen as a symbol of Spanish culture.

The bullfight is above all about the demonstration of style, technique and courage by its participants. While there is usually no doubt about the outcome, the bull is not viewed as a sacrificial victim — it is instead seen by the audience as a worthy adversary, deserving of respect in its own right. Bulls learn fast and their capacity to do so should never be underestimated. Indeed, a bullfight may be viewed as a race against time for the matador, who must display his bullfighting skills before the animal learns what is going on and begins to thrust its horns at something other than the cape. A hapless matador may find himself being pelted with seat cushions as he makes his exit.

The audience looks for the matador to display an appropriate level of style and courage and for the bull to display aggression and determination. For the matador, this means performing skillfully in front of the bull, often turning his back on it to demonstrate his mastery over the animal. The skill with which he delivers the fatal blow is another major point to look for. A skillful matador will achieve it in one stroke. Two is barely acceptable, while more than two is usually regarded as a botched job.

The moment when the matador kills the bull is the most dangerous point of the entire fight, as it requires him to reach between the horns, head on, to deliver the blow. Matadors are at the greatest risk of suffering a goring at this point. Gorings are not uncommon and the results can be fatal. Many bullfighters have met their deaths on the horns of a bull, including one of the most celebrated of all time, Manolete, who was killed by a bull named Islero, raised by Miura, and Paquirri, who was killed by a bull named Avispado.

In Spanish-speaking countries, when the bull charges through the cape, the crowd cheers saying Olé. If the matador has done exceptionally well, he will be given a standing ovation by the crowd, throwing hats and roses into the arena to show their appreciation. The successful matador will also receive one or two severed ears, and even the tail of the bull, depending on the quality of his performance. If the bull’s performance was also exceptional, the public may petition the president for a vuelta. This is when the crowd applauds as the dead bull is dragged once around the ring.

Some separatists despise bullfighting because of its association with the Spanish nation and its blessing by the Franco regime as the fiesta nacional. Despite the long history and popularity of bullfighting in Barcelona, that at one time had three bullrings, [citation needed] Catalan nationalism played an important role in Barcelona's recent symbolic vote against bullfighting.[4] However, even Jon Idigoras, a former Basque Batasuna leader, was a novillero before becoming a politician.

Another current of criticism comes from aficionados themselves, who may despise modern developments such as the defiant style ("antics" for some) of El Cordobés or the lifestyle of Jesulín de Ubrique, a common subject of Spanish gossip magazines. His "female audience"-only corridas were despised by veterans, many of whom reminisce about times past, comparing modern bullfighters with early figures.

Fin-de-siècle Spanish regeneracionista intellectuals protested against what they called the policy of pan y toros ("bread and bulls"), an analogue of Roman panem et circenses promoted by politicians to keep the populace content in its oppression.

Popularity

A 2002 Gallup poll found that nearly 70% of Spaniards express "no interest" in bullfighting while the remaining 30% express "some" or "a lot" of interest. The poll also found significant generational variety, with over 50% of those 65 and older expressing interest, compared with less than a quarter of those 25–34 years of age.[5].

Furthermore, bullfighting popularity varies a lot between different areas in countries like Spain or Mexico. In Spain, the fiesta is most popular in Andalusia and Madrid, while it has little following in Galicia or the Balearic Islands. In the Canary Islands, bullfighting is formally forbidden.

Animal concerns

Bullfighting is banned in many countries; people taking part in such activity would be liable for terms of imprisonment for animal cruelty. "Bloodless" variations, though, are permitted and have attracted a following in California, and France. In Spain, national laws against cruelty to animals have abolished most archaic spectacles of animal cruelty, but specifically exempt bullfighting. Over time, Spanish regulations have reduced the goriness of the fight, but only for the matadors and horses, introducing the padding for picadors' horses and mandating full-fledged operating rooms in the premises. In 2004, the Barcelona city council had a symbolic vote against bullfighting,[6] but bullfighting in Barcelona continues to this day, against the majority of public opinion. It has been estimated that 70% of the attendees at Barcelona's Monumental bullring are tourists.[7] Several other towns in Spain have banned bullfighting.[8]

Bullfighting guide The Bulletpoint Bullfight warns that bullfighting is “not for the squeamish” advising spectators to “be prepared for blood.” The guide details prolonged and profuse bleeding caused by horse-mounted lancers, the charging by the bull of a blindfolded, armored horse who is “sometimes doped up, and unaware of the proximity of the bull”, the placing of barbed darts by banderilleros, followed by the matador’s fatal sword thrust. The guide stresses that these procedures are a normal part of bullfighting and that death is rarely instantaneous. The guide further warns those attending bullfights to “Be prepared to witness various failed attempts at killing the animal before it lies down.” [9]

Bullfighting has been criticized by animal rights activists as a gratuitously cruel blood sport, because they believe that animals should not be tortured, killed or abused for entertainment. The bull suffers severe stress or a slow, painful death. A number of animal rights or animal welfare activist groups undertake anti-bullfighting actions in Spain and other countries. In Spanish, opposition to bullfighting is referred to as antitaurina.

In August 2007, state-run Spanish TV cancelled live coverage of bullfights claiming that the coverage was too violent for children who might be watching, and that live coverage violated a voluntary, industry-wide code attempting to limit "sequences that are particularly crude or brutal". [10]

See also

- People:

- Santiago Wealands Tapia Robson, the first Anglo-Spanish bullfighter

- List of bullfighters

- Ordóñez (bullfighter family)

- Romero dynasty

- Animals:

- Andalusian horse

- Fighting Cattle, bull breed used for fighting

- Iberian horse

- Lusitano, horse breed used in bullfighting

- Murciélago, a famous bull

- Styles of bullfighting:

- Chilean rodeo

- Cow fighting, Swiss style pitting cows against each other

- Jallikattu, unarmed bull-taming in Tamilnadu, India

- Tōgyū, bullfighting style of the Ryukyu Islands (particularly Okinawa) in Japan

- Literature and films:

- The Dangerous Summer, Ernest Hemingway's chronicle of the bullfighting rivalry between Luis Miguel Dominguín and his brother-in-law Antonio Ordóñez

- Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway's treatise on Spanish bullfighting (OCLC 704339)

- Shadow of a Bull, book by Maia Wojciechowska about a bullfighter's son, Manolo Olivar

- The Story Of A Matador, David L. Wolper's 1962 documentary about the life of the matador Jaime Bravo

References

- ^ "El Choque de Calor y la Muerte de los Toros durante Viajes Largos" MVZ. Ángel Guerra Oliveros. II congreso Iberamercano y XIII congreso nacional de veterinariostaurinos a.c, Zacatecas (México) 24, 25 y 26 de agosto de 2005.

- ^ Isaacson, Andy, (2007), "California's 'bloodless bullfights' keep Portuguese tradition alive", San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Vaches Pour Cash: L'Economie de L'Encierro Provencale, Dr. Yves O'Malley, Nanterre University 1987.

- ^ http://www.idausa.org/campaigns/sport/bull/alert.html

- ^ Encuesta Gallup: Interés por las corridas de toros (In Spanish)

- ^ Barcelona Passes Symbolic Vote Against Bullfighting

- ^ Bullfighting - Art or Cruelty to Animals

- ^ http://www.idausa.org/campaigns/sport/bull/alert.html

- ^ The Bulletpoint Bullfight, p. 6

- ^ http://www.news1130.com/news/international/article.jsp?content=w082258A | No more 'ole'? Matadors miffed as Spain removes bullfighting from state TV

Further reading

- Shadow of a Bull, book by Maia Wojciechowska about a bullfighter's son

External links

- Story Of A Matador, documentary about matadors produced by David L. Wolper in 1962

- Bullfighting in Andalucia, Spain from Andalucia.com

- Bullfighting style of Portugal

- Bullfighting FAQ

- Photos of Female Bullfighters in Spain Photo essay about Spanish female bullfighters by photojournalist Natsuko Utsumi.

- Images of Traditional Bullfighting in Yucatan

- ESPN "Travel 10: Bullfighting Aficionado Experiences

- "Haunted By The Horns", (2006) An ESPN online article about Matador Alejandro Amaya and Matador Eloy Cavazos. The article investigates why a matador chooses the profession.

- ToroPedia.com The English Language Online Encyclopedia of Bullfighting