Restoration of the Everglades

The restoration of the Everglades is an ongoing effort to correct damage done to the environment of southern Florida during the 20th century. As of 2008, it is the most expensive and comprehensive environmental repair attempt in history.[1][2] The degradation of the natural quality of the Everglades became an issue in the United States in the early 1970s after a jetport was proposed to be constructed in the Big Cypress Swamp. Studies indicated the jetport would have destroyed the ecosystem in South Florida and Everglades National Park.[3] After decades of destructive practices, both state and federal agencies worked to study how to balance the needs of the natural environment in South Florida, with urban and agricultural centers that had recently and rapidly grown in the Everglades.

The Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project (C&SF) built 1,400 miles (2,300 km) of canals and levees between the 1950s and 1971 throughout South Florida. Their last venture was the C-38 canal which straightened the Kissimmee River, causing catastrophic damage to animal habitats, and adversely affecting water quality in the Everglades. The canal became the first C&SF project to be reverted when parts of the 22 miles (35 km) of the canal began to be refilled with the material excavated from it, or backfilled, in the 1980s. The restoration of the Kissimmee River is projected to last until the year 2011.

When high levels of phosphorus and mercury were discovered in waterways in 1986, water quality became a focus for water management agencies. Costly and lengthy court battles were waged between various government entities to determine who was responsible for monitoring and enforcing water quality standards. Governor Lawton Chiles proposed a bill that determined which agencies would have that responsibility, and set deadlines for pollutant levels to decrease in water. Initially the bill was criticized by conservation groups for not being strong enough on polluters, but the Everglades Forever Act was passed in 1994. Since then, the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have surpassed expectations for achieving lower phosphorus levels.

A commission appointed by the governor published a report in 1995 stating that South Florida was unable to sustain its growth, and that the deterioration of the environment was negatively affecting daily life for all residents in South Florida. The environmental decline was predicted to harm tourism and commercial interests if nothing was done to halt current trends. In 1999, results of an eight-year study that evaluated the C&SF were submitted to U.S. Congress. The report warned that if no action was taken the region would rapidly deteriorate. A strategy called the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan was attached to restore portions of the Everglades, Lake Okeechobee, the Caloosahatchee River, and Florida Bay to undo the damage of the past 50 years. It would take 30 years to complete and cost $7.8 billion. Though the plan was passed into law in 2000, it has been compromised by politics and funding problems.

Background

Since the early 1800s the Everglades have been a subject of interest for agricultural development. The first attempt to drain the Everglades occurred in 1882 when a Pennsylvania land developer named Hamilton Disston constructed the first canals. Though these attempts were largely unsuccessful, Disston's purchase of land spurred tourism and real estate development of the state. The political motivations of Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward resulted in much more successful attempts at canal construction between 1906 and 1920. Recently reclaimed wetlands were used for growing sugarcane and vegetables, and urban development began to occur in the Everglades.[4]

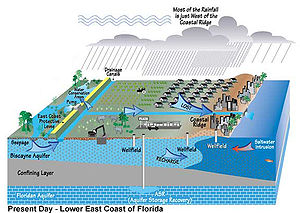

The 1926 Miami Hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane caused widespread devastation and flooding, prompting the Army Corps of Engineers to construct a dike around Lake Okeechobee. The four-story wall cut off the source of water from the Everglades. Floods from tropical storms in 1947 caused U.S. Congress to establish the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project (C&SF), responsible for constructing 1,400 miles (2,300 km) of canals and levees and hundreds of pumping stations and other water control devices. The C&SF established Water Conservation Areas (WCAs) of 37 percent of the original Everglades, that acted as reservoirs, and pumped extra water to the South Florida metropolitan area or flushed it into the Atlantic Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico.[5] The C&SF also established the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA), that grows the majority of sugarcane in the United States. When the EAA was first established, it comprised approximately 27 percent of the original Everglades.

Historically the Everglades comprised a third of the lower peninsula of Florida, but by the 1960s urban development and agricultural use had decreased the size considerably. The remaining 25 percent of the Everglades in their original state are protected in Everglades National Park, but the park was established prior to the C&SF, and it became dependent upon the actions of the C&SF to release water. As Miami and other metropolitan areas began to grow into the Everglades, political battles took place in the 1960s between Park management and the C&SF when the lack of water released to the park threw ecosystems into chaos. Furthermore, fertilizers used in the EAA began to alter soil and hydrology in Everglades National Park, causing the proliferation of exotic plant species.[6] However, a proposition to build a massive jetport in the Big Cypress Swamp in 1969 focused attention on the degraded natural systems in the Everglades. For the first time, the Everglades became a subject of environmental conservation.[7]

Priority Everglades

In the 1970s protecting the environment became a national priority. Time magazine declared it the Issue of the Year in January 1971, reporting that it was rated as Americans' "most serious problem confronting their community—well ahead of crime, drugs and poor schools".[8] South Florida became a more poignant subject when the region experienced another severe drought from 1970 to 1975; Miami received only 33 inches (84 cm) of rain in 1971—22 inches (56 cm) less than average.[9] With the assistance of governor's aide Nathaniel Reed and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Arthur R. Marshall, politicians began to take action on the Everglades. Governor Reubin Askew implemented the Land Conservation Act in 1972, that allowed the state to use voter-approved bonds of $240 million to purchase land considered to be environmentally unique and irreplaceable.[10] Since then, Florida has purchased more land for public use than any other state.[11] In 1972 President Richard Nixon declared the Big Cypress Swamp, the intended location for the Miami jetport in 1969, would be federally protected.[12] Big Cypress National Preserve was established in 1974,[13] and Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve was created in the same year.[10] In 1976 Everglades National Park was declared an International Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO,[14] who also listed the park as a World Heritage Site in 1979. The Ramsar Convention named the Everglades as a Wetland of International Importance in 1987.[15] Only two other locations on earth have appeared on all three lists: Lake Ichkeul in Tunisia, and Srebarna Lake in Bulgaria.[16]

Kissimmee River

In the 1960s the C&SF came under increased scrutiny from government overseers and conservation groups. Critics maintained it was comparable to the Great Depression-era dam-building Tennessee Valley Authority in size, and that their projects had run into the billions of dollars without any apparent resolution or plan.[17] The projects of the C&SF have been characterized as "crisis and response" cycles that "ignored the consequence for the full system, assumed certainty of the future, and succeeded in solving the momentary crisis, but set in motion conditions that exaggerate future crises".[18] The last project began in 1962: it was to build a canal to straighten the winding floodplain of the Kissimmee River, that had historically fed Lake Okeechobee which in turn fed the Everglades. Marjory Stoneman Douglas later wrote that the C&SF projects were "interrelated stupidity" that was crowned by the C-38 canal, completed in 1971.[19] Construction of the C-38 canal cost $29 million, for a channel 52 miles (84 km) long that replaced the meandering river of 90 miles (140 km), and approximately 45,000 acres (18,000 ha) of marshland were supplanted with retention ponds, dams, and vegetation.[20] Due to loss of habitat, the region experienced a drastic loss of waterfowl, wading birds, and game fish.[21] The reclaimed floodplains were taken over by agricultural endeavors that caused fertilizers and insecticides to be flushed into Lake Okeechobee. Even before the canal was finished conservation organizations, and sport fishing and hunting groups were calling for the restoration of the Kissimmee River.[20]

Arthur R. Marshall led the efforts to undo the damage. According to Douglas, Marshall was as successful in portraying the Everglades from the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes to Florida Bay, including the atmosphere, climate, and limestone as a single organism. The cause of restoring the Everglades became a priority to politicians rather than being the preserve of conservation organizations. Douglas observed, "Marshall accomplished the extraordinary magic of taking the Everglades out of the bleeding-hearts category forever".[22] His efforts led to recognition, and Arthur R. Marshall's name would eventually grace a national wildlife refuge in Palm Beach County and a chair at the University of Florida.[23] At the insistent urging of Marshall, newly elected Governor Bob Graham announced the formation of the "Save Our Everglades" campaign in 1983, and in 1985 Graham lifted the first shovel of backfill for a portion of the C-38 canal.[24] Within a year the area was covered with water, was returning to its original state.[25] Graham declared that by the year 2000, the Everglades would resemble its predrainage state as much as possible.[24] In 1992 the Kissimmee River Restoration Project was approved by Congress in the Water Resources Development Act. The project was estimated to cost $578 million to convert only 22 miles (35 km) of the canal; the cost was designed to be divided between the State of Florida and the U.S. government, with the state being responsible for purchasing land to be restored.[26] A project manager for the Army Corps of Engineers explained in 2002, "What we're doing on this scale is going to be taken to a larger scale when we do the restoration of the Everglades".[27] The entire project is estimated to be completed by 2011.[26]

Water quality

Attention to water quality in South Florida became an issue in 1986 when a widespread algal bloom occurred in one-fifth of Lake Okeechobee. The bloom was discovered to be the result of fertilizers backpumped from the Everglades Agricultural Area.[28] Although laws had stated in 1979 that the chemicals used in the EAA should not be deposited into Lake Okeechobee, they were instead flushed into the canals that fed the Everglades Water Conservation Areas, and eventually pumped back into Lake Okeechobee.[9] Microbiologists discovered that phosphorus, regardless of how it assists the growth of plants, destroys periphyton—one of the basic building blocks of marl in the Everglades. Marl is one of two types of Everglades soil, along with peat; it is found where parts of the Everglades are flooded for lesser periods of time as layers of periphyton dry.[29] Most phosphorus also rids peat of dissolved oxygen and promotes algae, causing native invertebrates to die, and sawgrass to be replaced with invasive cattails, that grow too tall and thick for birds and alligators to nest in.[30] Tested water showed 500 parts per billion (ppb) of phosphorus near sugarcane fields. State legislation in 1987 mandated that by 1992 a 40 percent reduction of phosphorus should occur. A costly legal battle took place from 1988 to 1992 between the State of Florida, U.S. government, and agricultural interests about who was responsible for water quality standards and the for the maintenance of Everglades National Park and the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge.[9]

Another water quality issue was the discovery in the 1980s of mercury in fish. Because mercury is damaging to people, warnings were posted for fishermen that cautioned against eating fish caught in South Florida, and scientists became very alarmed when a Florida panther was found dead near Shark River Slough with mercury levels high enough to be fatal to humans.[31] When mercury is ingested it adversely affects the central nervous system, and can cause brain damage and birth defects.[32] Studies of mercury levels found that it is bioaccumulated through the food chain: animals that are lower on the chain have decreased amounts, but as larger animals eat them, the amount of mercury is multiplied. The dead panther's diet consisted of small animals of raccoons and young alligators. The source of the mercury was found to be waste incinerators and fossil fuel power plants that expelled the element in the atmosphere, which came down as rain, or dust in the dry season.[31] Naturally occurring bacteria in the Everglades that function to reduce sulfur also transformed mercury deposits into methylmercury. This process was more dramatic in areas where flooding was not as prevalent. With reduced power plant and incinerator omissions required, the levels of mercury found in larger animals has decreased as well: approximately a 60 percent decrease in fish and a 70 percent decrease in birds, though some levels still remain a health concern for people.[31]

Everglades Forever Act

In an attempt to resolve the political quagmire of water quality, Governor Lawton Chiles introduced a bill in 1994 to clean up water in the EAA that was being released to the lower Everglades. The bill stated that the "Everglades ecosystem must be restored both in terms of water quality and water quantity and must be preserved and protected in a manner that is long term and comprehensive".[33] It ensured that the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) would be responsible for researching water quality, enforcing water supply improvement, controlling exotic species, and collecting taxes, with the aim of decreasing the levels of phosphorus in the Everglades. It allowed for purchase of lands where pollutants would be sent to "treat and improve the quality of waters coming from the EAA".[34]

Critics of the bill argued the deadline for meeting the standards was unnecessarily delayed until 2006, a period of 12 years, to enforce better water quality. They also maintained that it did not force sugarcane growers, who were the primary polluters, to pay enough of the costs, and it increased the threshold of what was an acceptable amount of phosphorus in water from 10 ppb to 50 ppb.[35] Governor Chiles initially named it the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Act, but Douglas was so unimpressed with the action it took against polluters that she wrote to Chiles and demanded her named be stricken from it.[35] The Florida legislature passed the Act in 1994 despite criticism. The SFWMD has stated that its actions have exceeded expectations earlier than anticipated,[36] by creating Stormwater Treatment Areas (STA) within the EAA that contain a calcium-based substance such a lime rock layered between peat, and filled with calcareous periphyton. Early tests by the Army Corps of Engineers found this method reduced phosphorus levels from 80 ppb to 10 ppb.[37] The STAs are intended to treat water until the phosphorous levels are low enough to be released into the Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge or other WCAs.

Wildlife concerns

The sprawl of urban areas into wilderness has a substantial impact on wildlife. Several species of animals are considered endangered in the Everglades region. One animal that has benefited from endangered species protection in the past is the alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Their range once extended far from the Everglades and they were abundant. Their construction of alligator holes gives refuge to many other animals, often allowing many species survival during times of drought. Though alligators are no longer an endangered species, their territories are considerably smaller than they once were, and their body mass is lower than it has been in the past. Because there are fewer of them, their role during droughts is more limited.[38]

American crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus) are also natives to the region. They have been designated as endangered since 1975. Unlike the related alligators, crocodiles tend to live in brackish or salt water habitats such as estuarine or marine coasts. Their most significant threat is disturbance by people; too much contact with humans causes females to abandon their nests. Males in particular roam over large territories and have been victims of vehicle collisions when attempting to cross US 1 and Card Sound Road in the Florida Keys. There are an estimated 500 to 1,000 crocodiles in southern Florida.[39]

The most critically endangered of any animal in the Everglades region is the Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi), a species that once lived throughout the Southeastern United States. The panther is most threatened by urban encroachment, since males require approximately 200 square miles (520 km2) for breeding territory. Within that range, a male and two to five females may live. When habitat is lost, panthers will fight over territory. After vehicle collisions, the second most frequent cause of death for panthers are intra-species aggression. A limited genetic pool is also a danger; there were only between 25 and 30 in the wild in 1995. Biologists introduced eight female Texas cougars (Puma concolor) to diversify genes, and there are between 80 and 100 panthers in the wild as of 2008.[40] In the 1990s urban expansion crowded panthers from southwestern Florida as Naples and Ft. Myers began to expand into the western Everglades and Big Cypress Swamp. Agencies such as the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service were in charge of maintaining the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, yet still approved 99 percent of all permits to build in wetlands and panther territory.[41]

Perhaps the most dramatic loss of any group of animals has been to wading birds. Their numbers were estimated by eyewitness accounts to be approximately 2.5 million in the late 19th century. However, snowy egrets (Egretta thula), roseate spoonbills (Platalea ajaja), and reddish egrets (Egretta rufescens) were hunted to the brink of extinction for their colorful feathers that were used in women's hats. After about 1920 when the fashion passed, their numbers returned in the 1930s, but over the next 50 years actions by the C&SF further disturbed populations. When the canals were constructed, natural water flow was restricted from the mangrove forests near the coast of Florida Bay. From one wet season to the next, fish were unable to reach traditional locations to repopulate it when water was withheld by the C&SF. Birds were forced to fly farther and farther from their nests to forage for food. By the 1970s, bird numbers had decreased 90 percent. Many of the birds moved to smaller colonies the WCAs to be closer to a food source, making them more difficult to count. Yet they remain significantly fewer in number than their populations before canals were constructed.[42][43]

Invasive species

With the sharp rise in human population the problem of exotic plant and animal species has grown. Many species of plants were been brought in from Asia, Central America, or Australia as decorative landscaping. Exotic animals imported by the pet trade have escaped or been released. Biological controls that keep invasive species smaller in size and fewer in number in their native lands often do not exist in the Everglades, and they compete with embattled native species for food and space. Of imported plant species, melaleuca trees (Melaleuca quinquenervia) are cause for the most concern. Melaleucas grow taller in the Everglades, on average, 100 feet (30 m), as opposed to the 25 feet (7.6 m) to 60 feet (18 m) in their native Australia. They were brought to southern Florida as windbreaks and deliberately seeded in marsh areas because they take up vast amounts of water. In a region that is regularly shaped by fire, melaleucas are fire-resistant and their seeds are more efficiently spread by fire. They grow too dense for wading birds with large wingspans to nest in, and they choke out native vegetation.[44] Costs of controlling melaleucas topped $2 million in 1998 for Everglades National Park. In Big Cypress National Preserve, melaleucas at their most pervasive in the 1990s covered 186 square miles (480 km2).[45]

Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius) was brought to Southern Florida as an ornamental shrub, and was spread by bird droppings and other animals that ate its bright red berries. It thrives on abandoned agricultural land growing in dense forests, again too dense for wading birds to nest in. It especially thrives after hurricanes, and has invaded pineland forests. After Hurricane Andrew, scientists and volunteers cleared damaged pinelands of Brazilian pepper so the native trees would be able to return to their natural state.[46]

The species that is causing the most impediment to restoration is the Old World climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum), introduced in 1965. The fern grows rapidly and thickly on the ground, making passage for land animals such as black bears and panthers problematic. The ferns also grow as vines into taller portions of trees, and when fire occurs, it climbs the ferns in "fire ladders" to scorch portions of the trees that are not naturally resistant to fire the way the lower trunks are.[47]

Several animal species have been introduced to Everglades waterways, many of them as released exotic pets. Many tropical fish are released, the most detrimental being the blue talapia (Oreochromis aureus), which builds large nests in shallow waters. Talapias also consume vegetation which would normally be used by young native fishes for cover and protection.[48]

Reptiles have a particular affinity for the South Florida ecosystem. Virtually all lizards appearing in the Everglades have been introduced, such as the brown anole (Anolis sagrei sagrei) and the tropical house gecko (Hemidactylus mabouia). The herbivorous green iguana (Iguana iguana) can reproduce rapidly in wilderness habitats. However, the reptile that has earned media attention for its size and potential to harm children and domestic pets is the Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus) that has spread quickly throughout the area. The python can grow up to 20 feet (6.1 m) long, and is competing with alligators for the top of the food chain.[49]

Though exotic birds such as parrots and parakeets are also found in the Everglades, their impact is negligible. Conversely, perhaps the animal that causes the most damage to native wildlife is the domestic or feral cat. Across the U.S., cats are responsible for approximately a billion bird deaths annually. They are estimated to number 640 per square mile; cats living in suburban areas have devastating effects on migratory birds and marsh rabbits.[50]

Homestead Air Force Base

In 1992 Hurricane Andrew hit Miami, with catastrophic damage to Homestead Air Force Base in Homestead. An early plan in 1993 to revamp the property and turn it into a commercial airport was met with enthusiasm from local municipal and commercial entities hoping to recoup the $480 million lost by the destruction of the base. A cursory environmental study was deemed insufficient by local conservation groups, who threatened to sue to stop the acquisition when estimates of 650 flights a day were projected. Groups had previously been alarmed by a 1990 designation of Homestead Air Force Base on the list of the U.S. government's most polluted properties.[51] Their concerns also included noise, and the inevitable collisions with birds using the mangrove forests as rookeries. The air force base is located between Everglades National Park and Biscayne National Park. In 2000, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt and the director of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency expressed their opposition to the project, despite other Clinton Administration entities previously working to ensure the base would be turned over to local agencies quickly and smoothly as "a model of base disposal".[52][53] Despite attempts to make the base more environmentally friendly, in 2001 local proponents of the airport lost federal support. On March 31, 1994, the base was designated as an Air Reserve Base and continues in that capacity as of 2008.[54]

Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

Sustainable South Florida

Despite the successes of the Everglades Forever Act, and the decreases in mercury levels, the focus intensified on the Everglades in the 1990s as quality of life in the South Florida metropolitan areas diminished. It was becoming clear that urban populations were consuming increasingly unsustainable levels of natural resources. A report entitled "The Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida", submitted to Lawton Chiles in 1995, identified the problems the state and municipal governments were facing. The report remarked that the degradation of the natural quality of the Everglades, Florida Bay, and other bodies of water in South Florida would cause a significant decrease in tourism (12,000 jobs and $200 million annually) and income from compromised commercial fishing (3,300 jobs and $52 million annually).[55] The report noted the past abuses of the environment and the neglect that had brought the region to "a precipitous juncture" where the inhabitants of South Florida faced health hazards in polluted air and water, and crowded and unsafe urban conditions that hurt the reputation of the state. It noted that though the population had increased by 90 percent over the previous two decades, registered vehicles had increased by 166 percent, and maintaining roads and handling traffic congestion for half the amount of vehicles would require $26.3 billion over the next 20 years.[55] On the quality of water, the report stated, "(The) frequent water shortages ... create(s) the irony of a natural system dying of thirst in a subtropical environment with over 53 inches of rain per year".[55]

Restoration of the Everglades, however, briefly became a bipartisan cause in national politics. A controversial penny-a-pound tax on sugar was proposed to fund some of the necessary changes to be made to help clean water and make other improvements. It became a political battleground and seemed to stall without resolution. However, in the 1996 election year, Republican senator Bob Dole proposed Congress give the State of Florida $200 million to acquire land for the Everglades. Democratic Vice President Al Gore promised the federal government would purchase 100,000 acres (40,000 ha) of land in the EAA to turn it over for restoration. Politicking reduced the number to 50,000 acres (20,000 ha), but both Dole's and Gore's gestures were approved by Congress.[56]

Central and South Florida Project Restudy

As part of the Water Resources Development Act of 1992, Congress authorized an evaluation of the effectiveness of the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project. A report known as the "Restudy" was submitted to Congress in 1999. It cited indicators of harm to the system: a 50 percent reduction in the original Everglades, diminished water storage, harmful timing of water release, an 85 to 90 percent decrease in wading bird populations over the past 50 years, and the decline of output from commercial fisheries. Bodies of water including Lake Okeechobee, the Caloosahatchee River, St. Lucie estuary, Lake Worth Lagoon, Biscayne Bay, and the Everglades reflected drastic water level changes, hypersalinity, dramatic changes in marine and freshwater ecosystems. The Restudy noted the overall decline in water quality over the past 50 years was due to loss of wetlands that act as filters for polluted water.[57] It predicted that without intervention the entire South Florida ecoystem would deteriorate. Canals took 1,700,000,000 US gallons (6.4×109 L) of water to the ocean or gulf daily, so there was no opportunity for water storage, yet flooding was still a problem.[58] Without changes to the current system, the Restudy predicted water restrictions would be necessary every other year, and annually in some locations. It also warned that revising some portions of the project without dedicating efforts to an overall comprehensive plan would be insufficient and probably detrimental.[59]

After evaluating 10 plans, the Restudy recommended a comprehensive strategy that would cost $7.8 billion over 20 years. The plan advised taking the following actions:

- Create surface water storage reservoirs to capture 1.5 million acre-feet of water in several locations taking up 181,300 acres (73,400 ha).[60]

- Create water preserve areas to treat runoff water between Miami-Dade and Palm Beach and the eastern Everglades.[60]

- Manage Lake Okeechobee as an ecological resource to avoid the drastic rise and fall of water levels in the lake that are harmful to aquatic plant and animal life, and disturb the lake sediments.[60]

- Improve water deliveries to estuaries to reduce the rapid discharge of excess water to the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries that upset nutrient balances and cause lesions on fish. Stormwater discharge would be sent instead to reservoirs.[61]

- Underground water storage so that 1,600,000,000 US gallons (6.1×109 L) a day could be stored in wells or reservoirs in the Floridan Aquifer, to be used later in dry periods, in a method called Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR).[61]

- Treatment wetlands used as Stormwater Treatment Areas throughout 35,600 acres (14,400 ha) that would decrease the amount of pollutants to the environment.[61]

- Improve water deliveries to the Everglades by increasing them at a rate of approximately 26 percent into Shark River Slough.[61]

- Remove barriers to sheetflow by destroying or removing 240 miles (390 km) of canals and levees, specifically the Miami Canal. Reconstruct the Tamiami Trail from a highway to culverts and bridges to allow sheetflow, or the shallow slow drift of the river, to a more natural stream of water into Everglades National Park.[62]

- Store water in quarries and reuse wastewater by employing existing quarries to supply the South Florida metropolitan area as well as Florida Bay and the Everglades. Construct two wastewater treatment plants capable of discharging 220,000,000 US gallons (830,000,000 L) a day to recharge the Biscayne Aquifer.[62]

The implementation of all of the advised actions, the report stated, would "result in the recovery of healthy, sustainable ecosystems throughout south Florida".[63] The report admitted that it did not have all the answers, though no plan could.[64] However, it predicted that it would restore the "essential defining features of the pre-drainage wetlands over large portions of the remaining system", that populations of all animals would increase, and distribution patterns would return to natural states.[64] Critics expressed concern over some unused technology; scientists were unsure if the quarries would hold as much water as was being suggested, and whether the water would harbor harmful bacteria after being in the quarries. Overtaxing the aquifers was another concern—it was not a technique that had been previously attempted.[65]

Though it was optimistic, the Restudy noted,

"It is important to understand that the 'restored' Everglades of the future will be different from any version of the Everglades that has existed in the past. While it certainly will be vastly superior to the current ecosystem, it will not completely match the pre-drainage system. This is not possible, in light of the irreversible physical changes that have made to the ecosystem. It will be an Everglades that is smaller and somewhat differently arranged than the historic ecosystem. But it will be a successfully restored Everglades, because it will have recovered those hydrological and biological patterns which defined the original Everglades, and which made it unique among the world’s wetland systems. It will become a place that kindles the wildness and richness of the former Everglades."[66]

The report was the result of many cooperating agencies that often had conflicting goals. An initial report was submitted to Everglades National Park management who attested not enough water would be released to the park quickly enough—that the priority went to delivering water to urban areas. When they threatened to refuse to support it, the plan was rewritten to provide more water to the park. However, the Miccosukee Indians have a reservation in between the park and canals, and they threatened to sue to ensure their tribal lands and a $50 million casino would not be flooded.[67] Other special interests were also concerned that businesses and residents would take second priority under nature. The Everglades, however, proved to be a bipartisan cause. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) was authorized by the Water Development Act of 2000, signed into law by President Bill Clinton on December 11, 2000, and approved the immediate use of $1.3 billion for implementation to be split by the federal government and other sources.[68]

Implementation

Since CERP was signed, the State of Florida reports that it has spent more than $2 billion on the various projects. More than 36,000 acres (15,000 ha) of Stormwater Treatment Areas (STA) have been constructed to filter 2,500 short tons (2,300 t) of phosphorous from Everglades waters. An STA covering 17,000 acres (6,900 ha) was constructed in 2004, making it the largest manmade wetland in the world. Fifty-five percent of the land necessary for restoration has been purchased by the State of Florida, totaling 210,167 acres (85,052 ha). A plan named "Acceler8", to hasten the construction and funding of the project, was put into place, spurring the start of six of eight construction projects, including that of three large reservoirs.[69]

Despite the bipartisan goodwill and declarations of the importance of the Everglades, the region still remains in danger. Political maneuvering continues to impeded CERP; sugar lobbyists promoted a bill in the Florida legislature in 2003 that increased the acceptable amount of phosphorus in Everglades waterways from 10 ppb to 15 ppb, and extended the deadline for the mandated decrease by 20 years.[70] It was eventually compromised to a deadline in 2016. Environmental organizations express concern that attempts to speed up some of the construction through Acceler8 is politically motivated; the six projects Acceler8 focuses on do not provide more water to natural areas in desperate need of it, but rather to projects in populated areas bordering the Everglades, suggesting that water is being diverted to make room for more people in an already overtaxed environment.[71] Though Congress promised half the funds for restoration, the War in Iraq began, and two of CERP's major supporters in Congress retired, leaving it in limbo. According to a story in The New York Times, state officials say the restoration is lost in a maze of "federal bureaucracy, a victim of 'analysis paralysis'".[72] The lack of response from Congress prompted Governor Charlie Crist to travel to Washington D.C. in February 2008 and inquire about the promised funds.[73] Florida still receives a thousand new residents daily and lands slated for restoration and wetland recovery are often bought and sold before the state has a chance to bid on them. The competitive pricing of real estate also drives it beyond the purchasing ability of the state.[74]

Because the State of Florida is assisting with purchasing lands and funding construction, some of the programs under CERP are vulnerable to state budget cuts. In 2008 Florida announced between $4 and $5 billion worth of cuts to many state programs. Everglades restoration was under consideration as one of the state-funded projects to be cut.[75]

See also

- History of Miami, Florida

- Indigenous people of the Everglades region

- Geography and ecology of the Everglades

- Draining and development of the Everglades

- Everglades National Park

Notes

- ^ Grunwald, p. 2.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (October 20, 2000). " Everglades Restoration Plan Passes House, With Final Approval Seen", The New York Times, p. 1.

- ^ J. V. F. (October, 1969). "Special Feature: Recent Developments in Everglades Controversy", BioScience, 19 (10), p. 926–927.

- ^ Dovell, Junius (July 1948). "The Everglades: A Florida Frontier", Agricultural History 22 (3), p. 187–197.

- ^ Light, Stephen, J. Walter Dineen "Water Control in the Everglades: A Historical Perspective" in Everglades : The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ Snyder G.H., J. Davidson, "Everglades Agriculture: Past, Present and Future" in Everglades : The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ Mueller, Marti (October 10, 1969). "Everglades Jetport: Academy Prepares a Model", Science, New Series, 166 (3902), p. 202–203.

- ^ "Issue of the Year: The Environment". Time. January 4, 1971. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ a b c Gunderson, Lance, et al (1995). "Lessons from the Everglades", BioScience, 45, Supplement: Science and Biodiversity Policy, pp. S66-S73.

- ^ a b "History". Fakahatchee State Preserve. Friends of Fakahatchee State Preserve. 2005. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Grunwald, p. 262

- ^ Nixon, Richard (February 8th, 1972). "51 - Special Message to the Congress Outlining the 1972 Environmental Program". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Laws & Policies". Big Cypress National Preserve. National Park Service. April 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Everglades National Park, Florida, United States of America". United Nations Environment Program. March 2003. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "Park Statistics". Everglades National Park. National Park Service. July 24, 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Maltby, E., P.J. Dugan, "Wetland Ecosystem Management, and Restoration: An International Perspective" in Everglades: The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ Davis, Jack (January 2003). "'Conservation is now a dead word': Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the transformation of American environmentalism." Environmental History, 8 (1) p. 53–76.

- ^ Holling, C.S. "The Structure and Dynamics of the Everglades System:Guidelines for Ecosystem Restoration" in Everglades : The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ Douglas (1987), p. 229.

- ^ a b

"Environmental Setting: The Altered System". Circular 1134. U.S. Geological Survey. November 2, 2004. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kissimmee River Restoration". Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville District. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Douglas (1987), p. 227.

- ^ George A. Smathers Libraries. "A Guide to the Arthur R. Marshall, Jr. Papers". Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b

Angier, Natalie (August 6, 1984). "Now You See It, Now You Don't". Time. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Douglas (1987), p. 232.

- ^ a b "Kissimee River History". Florida Department of Environmental Protection. 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Morgan, Curtis (December 15, 2002). "Florida's Kissimmee River Begins to Recover from Man-Made Damage", The Miami Herald

- ^ Lodge, p. 230.

- ^ Lodge, p. 37.

- ^ Davis, Steven. "Phosphorus Inputs and Vegetation Sensitivity in the Everglades" in Everglades: The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ a b c Lodge, p. 231–233.

- ^

"Mercury Studies in the Florida Everglades". FS-166-96. U.S. Geological Survey. November 9, 2004. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Florida Statutes (Supplement 1994) [Everglades Forever Act]". Chapter 373: Water Resources, Part IV. Management and Storage of Surface Waters, 373.4592 Everglades improvement and management. University of Miami School of Law. 1997. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^

Alexa, Micheal. "Handbook of Florida Water Regulation: Florida Everglades Forever Act". Chapter 373: Water Resources, Part IV. Management and Storage of Surface Waters, 373.4592 Everglades improvement and management. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Science. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Grunwald, p. 301.

- ^ "Long Term Plan Overview". South Florida Water Management District. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Periphyton-based Stormwater Treatment Area (PSTA) Technology" (pdf). The Journey to Restore America's Everglades. December 2003. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ Lodge, p. 236.

- ^ "American Crocodile" (pdf). Multi-Species Recovery Plan for South Florida. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ "Florida Panther Frequently Asked Questions". Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ Grunwald, p. 293.

- ^ Bancroft, G. Thomas, et al. "Relationships among Wading Bird Foraging Patterns, Colony Locations, and Hydrology in the Everglades", in Everglades: The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0963403028

- ^ Lodge, p. 233–234.

- ^ Lodge, p. 237–240.

- ^ Tasker, Georgia (August 22, 1998). "Federal Experts Warn of Alien Plant Invasion", The Miami Herald.

- ^ Lodge, p. 241.

- ^ Lodge, p. 242.

- ^ Lodge, p. 243–244.

- ^ Lodge, p. 244.

- ^ Lodge, p.244–245.

- ^ Zaneski, Cyril (August 24, 1998). "New Environmental Study Begins on Homestead, Fla., Airport Project", The Miami Herald.

- ^ Zaneski, Cyril (January 8, 2000). "Plans for Airport at Former Homestead, Fla., Air Forece Base Grounded", The Miami Herald.

- ^ Morgan, Curtis (January 6, 2001). "Miami-Area Officials' Plans for Air Force Base May Be Disrupted", The Miamim Herald.

- ^ "History of Homestead Air Force Base". United States Air Force. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ a b c "Chapter 1: Background and understanding". The Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida. State of Florida. October 1, 1995. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Grunwald, p. 311–313.

- ^ US Army COE and SFWMD, p. iii.

- ^ Tibbetts, John (August, 2000). "Making Amends: Ecological Restoration in the United States", Environmental Health Perspectives, 108 (8), p. A356–A361.

- ^ US Army COE and SFWMD, p. iv–v.

- ^ a b c US Army COE and SFWMD, p. vii.

- ^ a b c d US Army COE and SFWMD, p. viii.

- ^ a b US Army COE and SFWMD, p. ix.

- ^ US Army COE and SFWMD, p. x.

- ^ a b US Army COE and SFWMD, p. xi.

- ^ Grunwald, p. 319.

- ^ US Army COE and SFWMD, p. xii.

- ^ Kloor, Keith (May 19, 2000). "Everglades Restoration Plan Hits Rough Waters", Science, 288 (5469), p. 1166–1167.

- ^ "Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) of 2000". The Journey to Restore America's Everglades. November 4, 2002. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Restoring the River of Grass". Florida Department of Environmental Protection. 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ (April 21, 2003). "Everglades in Peril", The New York Times, Section A, p. 22.

- ^ Grunwald, Michael (October 14, 2004). "Fla. Steps In to Speed Up State-Federal Everglades Cleanup", The Washington Post, p. A03.

- ^ Goodnough, Abby (November 2, 2007). "Vast Effort to Save Everglades Falters as U.S. Funds Dwindle", The New York Times, Section A, p. 1.

- ^ Clark, Lesley (February 13, 2008). "Crist presses lawmakers for Glades funds", The Miami Herald, State and Regional News.

- ^ Barnett, p. 185.

- ^ Fineout, Gary (April 4, 2008). "Deep budget cuts in store for S. Florida", The Miami Herald, State and Regional News.

Bibliography

- Barnett, Cynthia (2007). Mirage: Florida and the Vanishing Water of the Eastern U.S., University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472115634

- Douglas, Marjory; Rothchild, John (1987). Marjory Stoneman Douglas: Voice of the River. Pineapple Press. ISBN 0910923941

- Grunwald, Michael (2006). The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743251075

- Lodge, Thomas E. (1994). The Everglades Handbook: Understanding the Ecosystem. CRC Press. ISBN 1884015069

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and South Florida Water Management District (April 1999). "Summary", Central and Southern Florida Project Comprehensive Review Study.