Great Pyramid of Giza

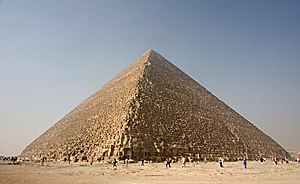

The Great Pyramid of Giza, also called Khufu's Pyramid or the Pyramid of Khufu, and Pyramid of Cheops, is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the Giza Necropolis bordering what is now Cairo, Egypt, and is the only remaining member of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It is believed the pyramid was built as a tomb for Fourth dynasty Egyptian King Khufu (Cheops in Greek) and constructed over a 20 year period concluding around 2560 BC. The Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years. Visibly all that remains is the underlying step-pyramid core structure seen today. Many of the casing stones that once covered the structure can still be seen around the base of the Great Pyramid. There have been varying scientific and alternative theories regarding the Great Pyramid's construction techniques. Most accepted construction theories are based on the idea that it was built by moving huge stones from a quarry and dragging and lifting them into place.

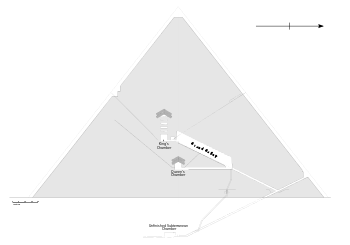

There are three known chambers inside the Great Pyramid. The lowest chamber is cut into the bedrock upon which the pyramid was built and was unfinished. The so-called[1] Queen's Chamber and King's Chamber are higher up within the pyramid structure. The Great Pyramid of Giza is the main part of a complex setting of buildings that included two mortuary temples in honor of Khufu (one close to the pyramid and one near the Nile), three smaller pyramids for Khufu's wives, an even smaller "satellite" pyramid, a raised causeway connecting the two temples, and small mastaba tombs surrounding the pyramid for nobles.

Building the pyramid

It is believed the pyramid was built as a tomb for Fourth dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu and constructed over a 14[2] to 20 year period concluding around 2560 BC.[3] Khufu's vizier, Hemon, or Hemiunu, is believed by some to be the architect of the Great Pyramid.[4] It is thought that, at construction, the Great Pyramid was 280 Egyptian royal cubits tall, 146.6 meters, but with erosion and the loss of its pyramidion, its current height is 138.8 m. Each base side was 440 royal cubits, with each royal cubit measuring 0.524 meters.[5] The total mass of the pyramid is estimated at 5.9 million tonnes. The volume, including an internal hillock, is believed to be roughly 2,500,000 cubic meters.[6] The first precision measurements of the pyramid were done by Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in 1880–82 and published as The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. Almost all reports are based on his measurements. Petrie found the pyramid is oriented 4' west of North and the second pyramid is similarly oriented.[7]

The pyrimad remained the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years,[8] unsurpassed until the 160 meter tall spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed c. 1300. The accuracy of the pyramid's workmanship is such that the four sides of the base have a mean error of only 58 millimeter in length, and 1 minute in angle from a perfect square. The base is horizontal and flat to within 15 mm. The sides of the square are closely aligned to the four cardinal compass points to within 3 minutes of arc and is based not on magnetic north, but true north. The completed design dimensions, as suggested by Petrie's survey and later studies, are estimated to have originally been 280 cubits in height by 4x440 cubits at it's base. These proportions equate to 2π to an accuracy of better than 0.05% which some Egyptologists consider to have been the result of deliberate design proportion. Verner wrote, "We can conclude that although the ancient Egyptians could not precisely define the value of π, in practise they used it".[9] John Romer shows how the use of a simple grid system would have obtained such a result without the necessity of mathematics.[10]

The Base

It is a little known fact that the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza is not a perfect square. The base is a 4 pointed star, each of the sides of the pyramid is concave, i.e. each face of the pyramid is indented from the apex to the midpoint of the base. This feature of its design can only be seen from the air, at certain times of the day. It was first photographed in 1940. Aerial photo by Groves, 1940.

This concavity divides each of the apparent four sides in half, creating a very special and unusual eight-sided pyramid; and it is executed to such an extraordinary degree of precision as to enter the realm of the uncanny. For, viewed from any ground position or distance, this concavity is quite invisible to the naked eye. The hollowing-in can be noticed only from the air, and only at certain times of the day. This explains why virtually every available photograph of the Great Pyramid does not show the hollowing-in phenomenon, and why the concavity was never discovered until the age of aviation. It was discovered quite by accident in 1940, when a British Air Force pilot, P. Groves, was flying over the pyramid. He happened to notice the concavity and captured it in the now-famous photograph. [11]

Casing stones

At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced by white 'casing stones' – slant-faced, but flat-topped, blocks of highly polished white limestone. Visibly all that remains is the underlying step-pyramid core structure seen today. In AD 1301, a massive earthquake loosened many of the outer casing stones, which were then carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad-Din al-Hasan in 1356 in order to build mosques and fortresses in nearby Cairo. The stones can still be seen as parts of these structures to this day. Later explorers reported massive piles of rubble at the base of the pyramids left over from the continuing collapse of the casing stones, which were subsequently cleared away during continuing excavations of the site. Nevertheless, many of the casing stones around the base of the Great Pyramid can be seen to this day in situ displaying the same workmanship and precision as has been reported for centuries. Petrie also found a different orientation in the core and in the casing measuring 193 centimeters ± 25 centimeters. He suggested a redetermination of north was made after the construction of the core, but a mistake was made, and the casing was built with a different orientation.[7]

Construction theories

There have been varying alternative theories proposed regarding the Pyramid's construction techniques. Most accepted construction theories are based on the idea that it was built by moving huge stones from a quarry and dragging and lifting them into place. The disagreements center on the method by which the stones were conveyed and placed. A recent theory proposes that the building blocks were manufactured in-place from a kind of "limestone concrete" [citation needed]. In addition to the many theories as to the techniques involved, there are also disagreements as to the kind of workforce that was used. One theory, suggested by the Greeks, posits that slaves were forced to work until the pyramid was done. This theory is no longer accepted in the modern era, however. Egyptologists believe that the Great Pyramid was built by tens of thousands of skilled workers who camped near the pyramids and worked for a salary or as a form of paying taxes until the construction was completed. The worker's cemeteries were discovered in 1990 by archaeologists Zahi Hawass and Mark Lehner. Verner posited that the labor was organized into a hierarchy, consisting of two gangs of 100,000 men, divided into five zaa or phyle of 20,000 men each, which may have been further divided according to the skills of the workers.[12]

One of the mysteries of the pyramid's construction is how they planned its construction. John Romer suggests that they used the same method that had been used for earlier and later constructions, laying out parts of the plan on the ground at a 1 to 1 scale. He writes that "such a working diagram would also serve to generate the architecture of the pyramid with a precision unmatched by any other means." He devotes a chapter of his book to the physical evidence that there was such a plan.[13]

Inside the Great Pyramid

The Great Pyramid is the only pyramid known to contain both ascending and descending passages. There are three known chambers inside the Great Pyramid. These are arranged centrally, on the vertical axis of the pyramid. From the entrance, an 18 meter corridor leads down and splits in two directions. One way leads to the lowest and unfinished chamber. This chamber is cut into the bedrock upon which the pyramid was built. It is the largest of the three, but totally unfinished, only rough-cut into the rock. The other passage leads to the Grand Gallery (49 m x 3 m x 11 m), where it splits again. One tunnel leads to the Queen's Chamber, a misnomer, while the other winds to intersect with the descending corridor. The Grand Gallery itself features a corbel haloed design and several cut "sockets" spaced at regular intervals along the length of each side of its raised base with a "trench" running along its center length at floor level. What purpose these sockets served is unknown. An antechamber leads from the Grand Gallery to the King's Chamber.[3]

King's Chamber

At the end of the lengthy series of entrance ways leading into the pyramid interior is the structure's main chamber, the King's Chamber. This chamber was originally 10 x 20 x 11.2 cubits, or about 5.25 m x 10.5 m x 6 m, comprising a double 10x10 cubit square, and a height equal to half the double square's diagonal. Some believe that this is consistent with the geometric methods for determining the Golden Ratio φ (phi), which can be derived from other dimensions of the pyramid, such that if φ had been the design objective, then π automatically follows to 'square the circle'.[14]

The sarcophagus of the King's Chamber was hollowed out of a single piece of Red Aswan granite and has been found to be too large to fit through the passageway leading to the chamber. Whether the sarcophagus was ever intended to house a body is unknown. It is too short to accommodate a medium height individual without the bending of the knees, a technique not practiced in Egyptian burial, and no lid was ever found. The King's Chamber contains two small shafts that ascend out of the pyramid. These shafts were once thought to have been used for ventilation, but this idea was eventually abandoned, which left Egyptologists to conclude they were instead used for ceremonial purposes. It is now thought that they were to allow the Pharaoh's spirit to rise up and out to heaven.[15]

The King's Chamber is lined with red granite brought from Aswan 935 km (580 miles) to the south in which blocks used for the roof are estimated to weigh 50 to 80 tonnes. [16] Egyptologists believe they were transported on barges down the Nile river.[17]

Queen's Chamber

The Queen's Chamber is the middle and the smallest, measuring approximately 5.74 by 5.23 meters, and 4.57 meters in height. Its eastern wall has a large angular doorway or niche. Egyptologist Mark Lehner believes that the Queen's chamber was intended as a serdab, a structure found in several other Egyptian pyramids, and that the niche would have contained a statue of the interred. The Ancient Egyptians believed that the statue would serve as a "back up" vessel for the Ka of the Pharaoh, should the original mummified body be destroyed. The true purpose of the chamber, however, remains uncertain.[15] The Queens Chamber has a pair of shafts similar to those in the King's Chamber, which were explored using a robot, Upuaut 2, created by the German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink. In 1992, Upuaut 2 discovered that these shafts were blocked by limestone "doors" with two eroded copper handles. The National Geographic Society filmed the drilling of a small hole in the southern door, only to find another larger door behind it.[18] The northern passage, which was harder to navigate due to twists and turns, was also found to be blocked by a door.[19]

Unfinished chamber

The "unfinished chamber" lies 27.5 meters below ground level and is rough-hewn, lacking the precision of the other chambers. Egyptologists suggest the chamber was intended to be the original burial chamber, but that King Khufu later changed his mind and wanted it to be higher up in the pyramid.[20]

Pyramid complex

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the main part of a complex setting of buildings that included two mortuary temples in honor of Khufu (one close to the pyramid and one near the Nile), three smaller pyramids for Khufu's wives, an even smaller "satellite" pyramid, a raised causeway connecting the two temples, and small mastaba tombs surrounding the pyramid for nobles. One of the small pyramids contains the tomb of queen Hetepheres (discovered in 1925), sister and wife of Sneferu and the mother of Khufu. There was a town for the workers of Giza, which included a cemetery, bakeries, a beer factory and a copper smelting complex. A few hundred meters south-west of the Great Pyramid lies the slightly smaller Pyramid of Khafre, one of Khufu's successors who is also commonly considered the builder of the Great Sphinx, and a few hundred meters further south-west is the Pyramid of Menkaure, Khafre's successor, which is about half as tall. In May 1954, 41 blocking stones were uncovered close to the south side of the Great Pyramid. They covered a 30.8 meter long rock-cut pit that contained the remains of a 43 meter long ship of cedar wood. In antiquity, it had been dismantled into 650 parts comprising 1224 pieces. This funeral boat of Khufu has been reconstructed and is now housed in a museum on the site of its discovery. A second boat pit was later discovered nearby.[21]

Media

See also

Notes

- ^ John Romer, in his The Great Pyramid: Ancient Egypt Revisited notes "By themselves, of course, none of these modern labels define the ancient purposes of the architecture they describe." p. 8

- ^ John Romer, basing his calculations on the known time scale for the Red pyramid, calculates 14 years - pp.74, schedule on pp 456-560.

- ^ a b Oakes & Gahlin (2002) p.66.

- ^ Shaw (2003) p.89.

- ^ Dilke (1987) pp.9,23.

- ^ Levy (2005) p.17.

- ^ a b Petrie (1883).

- ^ Collins (2001) p.234.

- ^ Verner (2003) p.70.

- ^ Romer (2007) pp.338-343

- ^ The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference by J.P. Lepre [pg.65]

- ^ Verner (2001) pp.75-82.

- ^ Romer, John, The Great Pyramid: Ancient Egypt Revisited, p. 327, pp. 329-337

- ^ Calter (2008) pp. 156-171, 548-551.

- ^ a b Oakes & Gahlin (2002) p.67.

- ^ Scarre (1999)

- ^ Romer (2007) pp.187-195

- ^ Gupton, Nancy (2003-04-04). "Ancient Egyptian Chambers Explored". National Geographic. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ "Third "Door" Found in Great Pyramid". National Geographic. 2002-09-23. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ "Unfinished Chamber". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ Clayton (1994) pp.48-49.

References

- Bauval, Robert &, Hancock, Graham (1996). Keeper of Genesis. Mandarin books. ISBN 0-7493-2196-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Calter, Paul A. (2008). Squaring the Circle: Geometry in Art and Architecture. Key College Publishing. ISBN 1-930190-82-4.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- Collins, Dana M. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195102345.

- Dilke, O.A.W. (1992). Mathematics and Measurement. University of California Press. ISBN 0520060725.

- Gahlin, Lucia (2003). Myths and Mythology of Ancient Egypt. Anness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84215-831-7.

- Levy, Janey (2005). The Great Pyramid of Giza: Measuring Length, Area, Volume, and Angles. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1404260595.

- Oakes, Lorana (2002). Ancient Egypt. Hermes House. ISBN 1-84309-429-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Petrie, Sir William Matthew Flinders (1883). The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. Field & Tuer. ISBN 0710307098.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Romer, John (2007). The Great Pyramid: Ancient Egypt Revisited. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-87166-2.

- Scarre, Chris (1999). The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, London. ISBN 978-0500050965.

- Seidelmann, P.Kenneth (1992). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-68-7.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198150342.

- Siliotti, Alberto (1997). Guide to the pyramids of Egypt; preface by Zahi Hawass. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN unknown.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Smyth, Piazzi (1978). The Great Pyramid. Crown Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-517-26403-X.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1703-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2003). The Pyramids. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1843541718.

- Lepre, J.P. (1990). The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0899504612.

External links

- Belless, Stephen. "The Upuaut Project Homepage". Upuaut Project. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help)

- Clemmons, Maureen. "How Many Caltechers Does It Take to Raise An Egyptian Obelisk?". Caltech News. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help)

- "The Giza Mapping Project". Oriental Institute. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help)

- Hawass, Dr. Zahi. "How Old are the Pyramids?". Ancient Egypt Research Associates. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help)