Old Latin

| Old Latin | |

|---|---|

| Region | Roman Republic |

| Extinct | developed into Classical Latin in 1st century BC |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

Old Latin (also called Early Latin or Archaic Latin) refers to the Latin language in the period before the age of Classical Latin; that is, all Latin before 75 BC.[1] The term prisca Latinitas distinguishes it in New Latin and Contemporary Latin from vetus Latina, in which "old" has another meaning.

The use of "old", "early" and "archaic" has been standard in publications of the corpus of Old Latin writings since at least the 18th century. The definition is not arbitrary but these terms refer to writings that utilize some spelling conventions and word forms not generally in use in works written under the Roman Empire. This article presents some of the major differences.

Time

In 1874 John Wordsworth used the definition:[2]

By Early Latin I understand Latin of the whole period of the Republic, which is separated very strikingly, both in tone and in outward form, from that of the Empire.

Although the differences are striking and can be easily identified by Latin readers, they are not such as to cause a language barrier. Latin speakers of the empire had no reported trouble understanding old Latin, except for the few texts that must date from the time of the kings, mainly songs. Thus the laws of the twelve tables, which began the republic, were comprehensible, but the carmen saliare, probably written under Numa Pompilius, was not entirely.

There is no sharp distinction between Old Latin as it was spoken in the republic and classical Latin, but the earlier grades into the later. The end of the republic was too late a termination for compilers after Wordsworth; Charles Edwin Bennett said:[3]

'Early Latin' is necessarily a somewhat vague term ... Bell, De locativi in prisca Latinitate vi et usu, Breslau, 1889,[4] sets the later limit at 75 B.C. A definite date is really impossible, since archaic Latin does not terminate abruptly, but continues even down to imperial times.

Bennett's own date of 100 B.C. did not prevail but rather Bell's 75 B.C. became the standard as expressed in the four-volume Loeb Library and other major compendia.

Corpus

Old Latin authored works began in the 3rd century B.C. These are complete or nearly complete works under their own name surviving as manuscripts copied from other manuscripts in whatever script was current at the time. In addition are fragments of works quoted in other authors.

Numerous inscriptions placed by various methods (painting, engraving, embossing) on their original media survive just as they were except for the ravages of time. Some of these were copied from other inscriptions. No inscription can be earlier than the introduction of the Greek alphabet into Italy but none survive from that early date. The imprecision of archaeological dating makes precise dates impossible but the earliest survivals are probably from the 6th century B.C. Some of the texts, however, surviving as fragments in the works of classical authors, had to have been composed earlier than the republic, in the monarchy. These are listed below.

Notable Old Latin fragments with estimated dates include:

- The Carmen Saliare (chant put forward in classical times as having been sung by the salian brotherhood formed by Numa Pompilius, approximate date 700 BC)

- The Praeneste fibula (7th century BC, but of authenticity questioned by some experts)

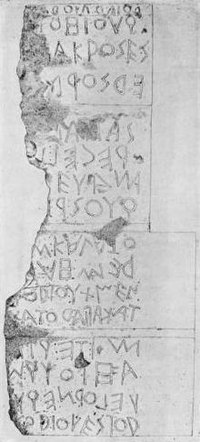

- The Forum inscription (illustration, right circa 550 BC under the monarchy)

- The Duenos inscription (circa 500 BC)

- The Castor-Pollux dedication (circa 500 BC)

- The Garigliano Bowl (circa 500 BC)

- The preserved fragments of the laws of the Twelve Tables (traditionally, 449 BC, attested much later)

- The Tibur pedestal (circa 400 BC)

- The Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus (186 BC)

- The Lapis Satricanus

- The Vase Inscription from Ardea

- The Corcolle Altar fragments

- The Carmen Arvale

- The Scipionum Elogia

The authors are as follows:

- Lucius Livius Andronicus (c. 280/260 BC–c. 200 BC)

- Gnaeus Naevius (ca. 264 – 201 BC)

- Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254–184 BC)

- Quintus Ennius (239 - c. 169 BC)

- Publius Terentius Afer (195/185–159 BC)

- Marcus Pacuvius

- Lucius Accius

- Gaius Lucilius

Script

Old Latin surviving in inscriptions is written in various forms of the Etruscan alphabet as it evolved into the Latin alphabet. The writing conventions varied by time and place until classical conventions prevailed. The works of authors in manuscript form were copied over into the scripts of other times. The original writing does not exist.

Orthography

Some differences between old and classical Latin were of spelling only; pronounciation was as in classical Latin:[5]

- Single for double consonants: Marcelus for Marcellus

- Double vowels for long vowels: aara for āra

- q for c before u: pequnia for pecunia

- xs for x: saxsum for saxum

- c for g: caius for gaius

These differences did not necessarily run concurrently with each other and were not universal; that is, c was used for both c and g.

Phonology

Phonological characteristics of older Latin are the case endings -os and -om (later Latin -us and -um), as well as the existence of diphthongs such as oi and ei (later Latin ū or oe, and ī). In many locations, classical Latin turned intervocalic /s/ into /r/, which is called rhotacism. This rhotacism had implications for declension: early classical Latin, honos, honoris; Classical honor, honoris ("honor"). Some Old Latin texts preserve /s/ in this position, such as the Carmen Arvale's lases for lares.

Grammar and morphology

Nouns

First declension (a)

The 'A-Stem Declension'. Nouns of this declension usually end in –a and are typically feminine.

| puella, –aī girl, maiden f. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | puella | puellai |

| Genitive | puellās/-es/-āī | puellōm/ -āsom |

| Dative | puellai | puellais/-eis/ -abos |

| Accusative | puellam | puellā |

| Ablative | puellād | puellais/-eis/ -abos |

| Vocative | puella | puellai |

| Locative | puellā | puellais/-eis |

Second declension (b)

The 'O-Stem Declension'. Nouns of this declension are either masculine or neuter.

| campos, –oi field, plain m. |

saxom, –oi rock, stone n. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | campos | campoi | saxom | saxa |

| Genitive | campī | campōm/ -ōsom |

saxī | saxōm/ -ōsom |

| Dative | campoi | campois | saxoi | saxois |

| Accusative | campom | campōs | saxom | saxa |

| Ablative | campōd | campois | saxōd | saxois/ -oes |

| Vocative | campe | campoi | saxe | saxoi |

| Locative | campō | campois | saxō | saxois/ -oes |

Note the genitive plural ending has two endings: the earlier -ōm, almost exactly like the Ancient Greek -ōn, and the later Archaic Latin form -ōsom. Because Latin single /s/ became /r/ between vowels, a phenomenon known as rhotacism, the later -ōsom evolved into the Classical Latin -ōrum.

Third declension (c)

The 'E-Stem' and 'I-Stem' Declension. This declension contains nouns that are masculine, feminine, and neuter.

| Regs –es king m. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | regs | reges |

| Genitive | regis | regōm |

| Dative | regei | regebos |

| Accusative | regem | reges |

| Ablative | regeid | regebos |

| Vocative | regs | reges |

| Locative | regei | regebos |

The nominative as regs instead of rex shows a common feature in Old Latin; the letter x was seldom used alone to designate the /ks/ or /gs/ sound, but instead, written as either 'ks', 'cs', or even 'xs'.

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns are among the most common thing found in Old Latin inscriptions. Note how in all three persons, the ablative singular ending is identical to the accusative singular.

| Ego, I | Tu, You | Suī, Himself, Herself, Etc. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ego | tu | - |

| Genitive | mis | tis | sei |

| Dative | mihei, mehei | tibei | sibei |

| Accusative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Ablative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Plural | |||

| Nominative | nōs | vōs | - |

| Genitive | nostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

vostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

sei |

| Dative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sibei |

| Accusative | nōs | vōs | sēd |

| Ablative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sēd |

Relative pronoun

In Old Latin, the relative pronoun is also another common concept, especially in inscriptions. Unfortunately, the forms are quite inconsistent and leave much to be reconstructed by scholars.

| queī, quaī, quod who, what | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Nominative | queī | quaī | quod |

| Genitive | quoius, quoios | quoia | quoium, quoiom |

| Dative | quoī, queī, quoieī, queī | ||

| Accusative | quem | quam | quod |

| Ablative | quī, quōd | quād | quōd |

| Plural | |||

| Nominative | ques, queis | quaī | qua |

| Genitive | quōm, quōrom | quōm, quārom | quōm, quōrom |

| Dative | queis, quīs | ||

| Accusative | quōs | quās | quōs |

| Ablative | queis, quīs | ||

Verbs

Old present and perfects

There is not much actual proof of the inflection of Old Latin verb forms and the few inscriptions we have hold many inconsistencies between forms. Therefore, the forms below are ones that are both proven by scholars through Old Latin inscriptions, and recreated by scholars based on other early Indo-European languages such as Greek and Italic dialects such as Oscan and Umbrian.

| Indicative Present: Sum | Indicative Present: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | som, esom | somos, sumos | sum | sumus | fac(e/ī)o | fac(e)imos | faciō | facimus |

| Second Person | es | esteīs | es | estis | fac(e/ī)s | fac(e/ī)teis | facis | facitis |

| Third Person | est | sont | est | sunt | fac(e/ī)d/-(e/i)t | fac(e/ī)ont | facit | faciunt |

| Indicative Perfect: Sum | Indicative Perfect: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | fuei | fuemos | fuī | fuimus | (fe)fecei | (fe)fecemos | fēcī | fēcimus |

| Second Person | fuistei | fuisteīs | fuistī | fuistis | (fe)fecistei | (fe)fecisteis | fēcistī | fēcistis |

| Third Person | fued/fuit | fueront/-erom | fuit | fuērunt | (fe)feced/-et | (fe)feceront/-erom | fēcit | fēcērunt/-ēre |

Bibliography

- Bennett, Charles Edwin (1910). Syntax of Early Latin. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- De Forest Allen, Frederic (1897). Remnants of Early Latin. Boston: Ginn & Company.

- Wordsworth, John (1874). Fragments and specimens of early Latin, with Introduction and Notes. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sources

- ^ "Archaic Latin" (html). The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ Wordsworth, John (1874). p. v.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bennett, C (1910). p. iii.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bell, Andreas (1889). De Locativi in prisca latinitate vi et usu, dissertatio inauguralis philologica. Breslau: typis Grassi, Barthi et soc (W. Friedrich).

- ^ De Forest Allen (1897). p. 8.

There were no such names as Caius, Cnaius

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)