Caboose

Template:Globalize/US and Canada

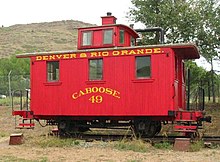

A caboose (North American railway terminology) or brake van or guard's van (British terminology) is a manned rail transport vehicle coupled at the end of a freight train. Although cabeese were once used on nearly every freight train, their use has declined and they are seldom seen on trains, except on locals and smaller railroads.

History

The caboose provided the train crew with a shelter at the rear of the train. They could exit the train for switching or to protect the rear of the train when stopped. They also inspected the train for problems such as shifting loads, broken or dragging equipment, and hot boxes. The conductor kept records and handled business from a table or desk in the caboose. For longer trips the caboose provided minimal living quarters, and was frequently personalized and decorated with pictures and posters.

Coal or wood was originally used to fire a cast iron stove for heat and cooking, later giving way to a kerosene heater. Now rare, the old stoves can be identified by several essential features. They were without legs, bolted directly to the floor, and featured a lip on the top surface to keep pans and coffee pots from sliding off. They also had a double-latching door, to prevent accidental discharge of hot coals due to the rocking motion of the caboose.

Early cabooses were nothing more than flat cars with small cabins erected on them, or modified box cars. The standard form of the American caboose had a platform at either end with curved grab rails to facilitate train crew members' ascent onto a moving train. A caboose was fitted with red lights called markers to enable the rear of the train to be seen at night. This has led to the phrase bringing up the markers to describe the last car on a train (these lights were officially what made a train a "train"). [1]

Originally lit with oil lamps, with the advent of electricity, later caboose versions incorporated an electrical generator driven by belts coupled to one of the axles, which charged a lead-acid storage battery when the train was in motion.

Cabooses are non-revenue equipment and were often improvised or retained well beyond the normal lifetime of a freight car. Tradition on many lines held that the caboose should be painted a bright red, though on many lines it eventually became the practice to paint them in the same corporate colors as locomotives. The Kansas City Southern did something unique: They left their cabooses unpainted, but ordered them with a stainless-steel car body. These were the exception to the rule of painting cabooses.

Brake or guards vans (UK & Australia)

- Main article: Brake van

In the UK the brake van performed a function similar to the caboose on North American railroads, being the accommodation for the train crew at the rear of the train, specifically the train guard, hence its alternative name.

In Great Britain, freight trains without a continuous train braking system in either the whole train or the rearmost section of the train (unfitted or partly fitted in UK railway parlance) were still prevalent in the 1970s but mostly eliminated by the 1980s. As of 2008, they are seen rarely on the main national rail network. On these trains, the brake van had two additional functions: the guard would use the brake van's brakes to assist with keeping the train under control on downwards gradients and whenever he could see that the locomotive's crew was attempting to slow the train; second, the brakes were left set on at a low setting all the time to ensure that the loose chain couplings often used between unfitted cars were kept taut, to minimise the risk of snapped coupling chains from the locomotive "snatching" or jerking, which was particularly problematic in the days of steam locomotives. Brake vans thus had a significant amount of ballast weight built into their structure to increase the available braking effort.

In the 1970s the requirement for fully fitted freight trains to end with a guards van was lifted and the guard would ride in the rearmost locomotive cab, which, since the UK mostly uses double-ended locomotives, has a good view of the train. These days brake vans are only used in certain special cases, for example in trains with unusual cargoes or track maintenance trains, and are consequently very rare.

In Australia, brake vans (or guard's vans - both terms were in common use) were often also used for carrying parcels and light freight and usually had large compartments and loading doors for such items. Some of the larger vans also included a compartment for passengers travelling on goods services or drovers travelling with their livestock.

Crew cars

On long distance Trans-continental trains travelling mainly through desert areas, crew cars have been instituted which are marshalled immediately behind the locomotives. These crew cars have accomotation for spare crew, cooking, sleeping and relaxation facilities. They are rebuild from surplus passenger cars and rail motors.

Caboose types

The form of cabooses varied over the years, with changes made both to reflect differences in service and improvements in design. The most commonly seen types are as follows:

Cupola or "standard" caboose

The most common caboose form in American railroad practice has a small windowed projection on the roof, called the cupola. The crew sat in elevated seats in order to inspect the train from this perch.

The invention of the cupola is generally attributed to T. B. Watson, a freight conductor on the Chicago and North Western Railway. In 1898 he wrote:

During the '60s I was a conductor on the C&NW. One day late in the summer of 1863 I received orders to give my caboose to the conductor of a construction train and take an empty boxcar to use as a caboose. This car happened to have a hole in the roof about two feet square. I stacked the lamp and tool boxes under the perforation end and sat with my head and shoulders above the roof ... (Later) I suggested putting a box around the hole with glass in, so I could have a pilot house to sit in and watch the train.

The position of cupola varied. In most eastern railroad cabooses the cupola was in the center of the car, but most western railroads preferred to put it toward the end of the car. Some conductors preferred to have the cupola toward the front, and other like it toward the rear of the train, and some just didn't care. ATSF conductors could refuse to be assigned to a train if they didn't have their caboose turned to face the way they preferred. However this would be a rare union agreement clause that could be used but not a regular issue.

The classic idea of the 'little red caboose' at the end of every train came about when cabooses were painted a reddish-brown, however some railroads (UP, and NKP for example) painted their cabooses yellow or red & white. The most notable was the Santa Fe which in the 1970's started a rebuild program for their cabooses in which the cars were painted bright red with a 8 foot diameter Santa Fe cross herald emblazoned on each side in yellow.

Bay window caboose

In a bay window caboose, the crew monitoring the train sits in the middle of the car in a section of wall that projects from the side of the caboose. The windows set into these extended walls resemble architectural bay windows, so the caboose type is called a bay window caboose. This type afforded a better view of the side of the train and eliminated the falling hazard of the cupola. It is thought to have first been used on the Akron, Canton and Youngstown Railroad in 1923, but is particularly associated with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which built all of its cabooses in this design starting from an experimental model in 1930. The bay window gained favor with many railroads also because it eliminated the need for additional clearances in tunnels and overpasses.

On the West Coast, the Milwaukee Road and the Northern Pacific Railway used these cars. Milwaukee Road rib side bay window cabooses are preserved at New Lisbon, Wisconsin, the Illinois Railway Museum, the Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad and Cedarburg, Wisconsin, among other places.

The Western Pacific Railroad was an early adopter of the type, building their own bay window cars starting in 1942 and acquiring this style exclusively from then on. Many other roads operated this type, including the Southern Pacific Railroad, Kansas City Southern, the Southern Railway, and the New York Central Railroad.

In the UK, brake vans are usually of this basic design: the bay window is known as a lookout or ducket.

Extended vision caboose

In the "Extended Vision" or "Wide Vision" caboose, the sides of the cupola project beyond the side of the carbody. Rock Island created some of these by rebuilding some standard cupola cabooses with windowed extensions applied to the sides of the cupola itself, but by far the greatest number have the entire cupola compartment enlarged. This model was introduced by the International Car Company and saw service on most U.S. railroads. The expanded cupola allowed the crew to see past the top of the taller cars that began to appear after World War II, and also increased the roominess of the cupola area.

Additionally, Monon Railroad had a unique change to the extended vision cabooses. They added a miniature bay to the sides of the cupola to enhance the views further. This created a unique look for their small fleet. Seven of the eight Monon-built cabooses have been saved. One was scrapped after an accident in Kentucky. The surviving cars are at the Indiana Transportation Museum (operational), the French Lick Museum (operational), the Kentucky Railroad Museum (fire damaged), and the Bluegrass Railroad Museum (unrestored but servicable). The remaining three are in private collections.

Transfer caboose

A transfer caboose looks more like a flat car with a shed bolted to the middle of it than it does a standard caboose. It is used in transfer service between rail yards or short switching runs, and as such lacks sleeping, cooking or restroom facilities. The ends of a transfer caboose are left open, with safety railings surrounding the area between the crew compartment and the end of the car.

A recent variation on the transfer caboose is the "pushing" or "shoving" platform. It can be any railcar where a brakeman can safely ride for some distance to help the engineer with visibility at the other end of the train. Flatcars and covered hoppers have been used for this purpose, but often the pushing platform is a caboose that has had its windows covered and welded shut and permanently locked doors. CSX uses former Missouri Pacific Railroad "shorty" transfer cabooses and marks them as pushing platforms.

Drover's caboose

Drover's cabooses looked more like combine cars than standard cabooses. The purpose of a drover's caboose was much more like a combine as well. On longer livestock trains in the West, the drover's caboose is where the livestock's handlers would ride between the ranch and processing plant. The train crew rode in the caboose section while the livestock handlers rode in the coach section. Drover's cabooses used either cupolas or bay windows in the caboose section for the train crew to monitor the train. The use of drover's cars on the Northern Pacific Railway, for example, lasted until the Burlington Northern Railroad merger of 1970. They were often found on stock trains originating in Montana.

Etymology

The first written evidence of the usage of caboose in a railroad context appeared in 1859 (not 1861, as cited by the Online Etymology Dictionary), as part of court records in conjunction with a lawsuit filed against the New York and Harlem Railway.[2] This suggests that caboose was probably in circulation among North American railroaders well before the mid-nineteenth century.

The railroad historian David L. Joslyn (a retired Southern Pacific Railroad draftsman), has connected caboose to kabhuis, a Middle Dutch word referring to the compartment on a sailing ship's main deck in which meals were prepared. Kabhuis is believed to have entered the Dutch language circa 1747 as a derivation of the obsolete Low German word kabhuse, which also described a cabin erected on a ship's main deck. However, further research indicates that this relationship was more indirect than that described by Joslyn.

Eighteenth century French naval records make reference to a cambose or camboose, which term described the food preparation cabin on a ship's main deck, as well as the range within. The latter sense apparently entered American naval terminology around time of the construction of the USS Constitution, whose wood-burning food preparation stove is officially referred to as the camboose. [3] These nautical usages are now obsolete: camboose and kabhuis became the galley when meal preparation was moved below deck, camboose the stove became the galley range, and kabuis the cookshack morphed into kombuis, which means kitchen in Afrikaans.

It is likely that camboose was borrowed by American sailors who had come into contact with their French counterparts during the American Revolution (recall that France was an ally and provided crucial naval support during the conflict). A New English Dictionary citation from the 1940s indicates that camboose entered English language literature in a New York Chronicle article from 1805 describing a New England shipwreck, in which it was reported that "[Survivor] William Duncan drifted aboard the canboose [sic]."[2] From this it could be concluded that camboose was part of American English by the time the first railroads were constructed. As the first cabooses were wooden shanties erected on flat cars (as early as the 1830s[4]) they would have resembled the cook shack on the (relatively flat) deck of a ship, explaining the adoption and subsequent corruption of the nautical term.

There is some disagreement on what constitutes the proper plural form of the word "caboose." Similar words, like goose (pluralized as "geese"), and moose (pluralized as "moose," no change) point to the reason for the difficulty in coming to a consensus. The most common pluralization of caboose is "cabooses," with some arguing that this is incorrect, and, as with the word moose, it should stay the same in plural form—that is, "caboose" should represent one or many. A less-seriously used pluralization of the word is "cabeese," following the pluralization rule for the word goose, which is "geese." This particular form is almost universally used in an attempt at humor (as, presumably, is "cabice").

It was common for railroads to officially refer to cabooses as "cabin cars."

Slang terms

Of all the implements of railroading, none has had more nicknames than the caboose. Many are of American or Canadian origin and seek to describe the vehicle or its occupants in derisive ways. Often heard amongst crews was "crummy" (as in a crummy place to live, not elegant, often too hot or too cold, and perhaps not especially clean), "clown wagon," "hack," "waycar," "dog house," "go cart," "glory wagon," "monkey wagon" (a term that indirectly insulted the principal functionary who rode therein, no doubt coined by an engineer), "brain box" (the conductor was supposedly the brains of the train, as opposed to the "hogger" or engineer, who was presumed to be pigheaded), "palace," "buggy" (Boston & Maine/Maine Central), "van" (Eastern and Central Canada, usage possibly derived from the UK term for the caboose), and "cabin", or a variation heard at least on the Southern Railway, "cab". There were others as well, some too profane to appear in print.

The small, two-axle cabooses that were widely used during the latter part of the nineteenth century were called "bobbers," which term described their riding characteristics on the relatively uneven track of the time. Bobbers tended to produce an unpleasant pitching motion that was usually not present in more modern, two truck models.

FRED

Until the 1980s, laws in the United States and Canada required that all freight trains have a caboose and a full crew, for safety. Technology eventually advanced such that the railroads, in an effort to save money and reduce crew members, stated that a caboose was unnecessary, since there were improved bearings and lineside detectors to detect hot boxes, and better designed cars to avoid problems with the load. The railroads also claimed that a caboose was also a dangerous place, as slack run-ins could hurl the crew from their places and even dislodge weighty equipment. With the introduction of FREDs (flashing rear-end device/end-of-train device; often referred to by railroad companies as an EOTD, an acronym for "end of train device"), the caboose was no longer necessary.

A FRED could be attached to the rear of the train to detect the train's air brake pressure and report any problems back to the locomotive. The FRED also detects movement of the train upon start-up and radios this information to the engineer so they know that all of the slack is out of the couplings and additional power can now be applied. The machines also have a blinking red light to warn following trains that a train is ahead. With the introduction of the FRED, the conductor moved up to the front of the train with the engineer and year by year, cabooses started to fade away. Very few cabooses remain in operation today, though they are still used for some local trains where it is convenient to have a brakeman at the end of the train to operate switches.

Preservation and reuse of cabooses

Although the caboose has largely fallen out of use, some are still retained by railroads in a reserve capacity. These cabooses are typically used in and around railyards. Other uses for the caboose include "special" trains, where the train is involved in some sort of railway maintenance, or as part of survey trains that inspect remote rail lines after natural disasters to check for damage. Others have been modified for use in research roles to investigate complaints from residents or business owners regarding trains in certain locations. Finally, some are coupled to trains for special events, including historical tours.

The Chihuahua al Pacífico Railroad in Mexico still uses cabooses to accompany their motorail trains between Chihuahua and Los Mochis.

Cabooses have also become popular for collection by railroad museums and for city parks and other civic uses, such as visitor centers. Several railroad museums roster large numbers of cabooses, including the Illinois Railway Museum with nineteen examples and the Western Pacific Railroad Museum at Portola, California with seventeen. Many shortline railroads still use cabooses today. Large railroads also use cabooses as "shoving platforms" or in switching service where it is convenient to have crew at the rear of the train.

Cabooses have been re-used as garden offices in private residences, and as portions of restaurants. Also, caboose motels have appeared, with the old cars being used as cabins.

References

- ^ Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (1948). Rules: Operating Department. p. 7.

- ^ a b Beebe, Lucius (1945). Highball! A Pageant of Trains. pp. 207–223.

- ^ USS Constitution Gun Deck

- ^ Union Pacific Railroad. "The Caboose's Early Uses".

External links

- The Caboose Station from the Potomac Eagle Scenic Railroad website: has information on introduction of the bay window caboose

- "The Wood Shanty Disappears" from Southern Pacific Bulletin, January, 1962, pp 22-26

- "The Colorful Caboose" from Trains Magazine (undated article)

Multimedia

- CBC Radio Archives Talking about the end of the caboose in Canada (1989)