Mystery fiction

Mystery fiction is a loosely-defined term that is often used as a synonym for detective fiction or crime fiction— in other words a novel or short story in which a detective (either professional or amateur) investigates and solves a crime. The term "mystery fiction" may sometimes be limited to the subset of detective stories in which the emphasis is on the puzzle element and its logical solution (cf. whodunit), as a contrast to hardboiled detective stories, which focus on action and gritty realism. However, in more general usage "mystery" may be used to describe any form of crime scene fiction, even if there is no mystery to be solved. For example, the Mystery Writers of America describes itself as "the premier organization for mystery writers, professionals allied to the crime writing field, aspiring crime writers, and those who are devoted to the genre." [1].

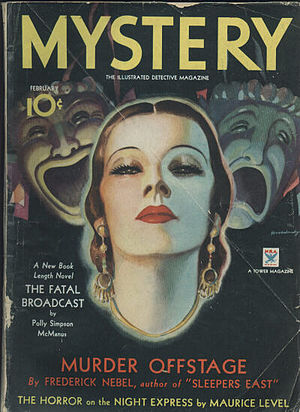

Although normally associated with the crime genre, the term "mystery fiction" may in certain situations refer to a completely different genre, where the focus is on supernatural mystery (even if no crime is involved). This usage was common in the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s, where titles such as Dime Mystery, Thrilling Mystery and Spicy Mystery offered what at the time were described as "weird menace" stories – supernatural horror in the vein of Grand Guignol. This contrasted with parallel titles of the same names which contained conventional hardboiled crime fiction. The first use of "mystery" in this sense was by Dime Mystery, which started out as an ordinary crime fiction magazine but switched to "weird menace" during the latter part of 1933.[2]

Beginnings

The earliest known murder mystery[3] and suspense thriller with multiple plot twists[4] and detective fiction elements[5] was "The Three Apples", or in Arabic, Hikayat al-sabiyya 'l-muqtula ("The Tale of the Murdered Young Woman"),[6] one of the tales narrated by Scheherazade in the One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights). In this tale, a fisherman discovers a heavy locked chest that is painted pink with flowers on it along the Tigris river and he sells it to the Abbasid Caliph, Harun al-Rashid, who then has the chest broken open only to find inside it the dead body of a young woman who was cut into pieces. Harun orders his vizier, Ja'far ibn Yahya, to solve the crime and find the murderer. This whodunit mystery may be considered an archetype for detective fiction.[7][8]

Modern mystery fiction is generally thought to begin with The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe (1841), followed by The Woman in White (1860) by Wilkie Collins. Collins wrote several more in this genre, including The Moonstone (1868) which is thought to be his masterpiece. The genre began to expand near the turn of century with the development of dime novels and pulp magazines. Books were especially helpful to the genre with many authors writing in the genre in the 1920s. An important contribution to mystery fiction in the 1920s was the development of the juvenile mystery by Edward Stratemeyer. Stratemeyer originally developed and wrote the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mysteries written under the Franklin W. Dixon and Carolyn Keene pseudonyms, respectively (and later written by his daughter, Harriet S. Adams, and other authors). The 1920s also gave rise to one of the most popular mystery authors of all time, Agatha Christie.

The massive popularity of pulp magazines in the 1930s and 1940s increased interest in mystery fiction. Pulp magazines decreased in popularity in the 1950s with the rise of television so much that the numerous titles available then are reduced to two today: Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. The detective fiction author Ellery Queen (pseudonym of Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee) is also credited with continuing interest in mystery fiction.

Interest in mystery fiction continues to this day because of various television shows which have used mystery themes and the many juvenile and adult novels which continue to be published. There is some overlap with "thriller" or "suspense" novels and like authors in those genres may consider themselves mystery novelists. Comic books and like graphic novels have carried on the tradition, and film adaptations have helped to re-popularize the genre in recent times.[9]

The Mystery Writers of America, an organization for authors of mystery, detective, and crime fiction, was founded in 1945. This popular genre has made the leap into the online world, spawning countless websites devoted to every aspect of the genre, with even a few supposedly written by real detectives.[1]

In recent years, Cozy mysteries have become popular. Cozy Mysteries usually take place in a small town and often include extra material such as recipes.

Classifications

Mystery fiction can be divided into several categories, among them the "cozy mystery", "police procedural", and "hardboiled" (for instance, Dashiell Hammett's The Maltese Falcon's main detective, Sam Spade).

See also

- Detective fiction

- List of crime writers

- List of female detective characters

- Category:Mystery novels

- List of mystery writers

- List of thriller authors

- Mystery film

- The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time

- Category:Mystery television

- Giallo

References

- ^ Mystery Writers of America

- ^ Haining, Peter (2000). The Classic Era of American Pulp Magazines. Prion Books. ISBN 1-85375-388-2.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, pp. 240–2, ISBN 0814332595

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 93, 95, 97, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 91 & 93, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, p. 240, ISBN 0814332595

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 86–91, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2006), The Arabian Nights Reader, Wayne State University Press, pp. 241–2, ISBN 0814332595

- ^ J. Madison Davis: How graphic can a mystery be?, World Literature Today, July-August 2007