Continental drift

Continental drift is the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other. The hypothesis that continents 'drift' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596 and was fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912. However, it was not until the development of the theory of plate tectonics in the 1960s, that a sufficient geological explanation of that movement was found.

History

Early history

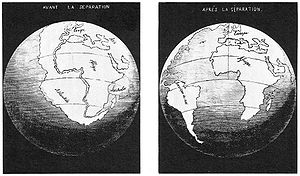

Abraham Ortelius (1597), Francis Bacon (1625), Benjamin Franklin, Antonio Snider-Pellegrini (1858), and others had noted earlier that the shapes of continents on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together. W. J. Kious described Ortelius' thoughts in this way:[1]

Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus ... suggested that the Americas were "torn away from Europe and Africa ... by earthquakes and floods" and went on to say: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents].

Wegener and his predecessors

The hypothesis that the continents had once formed a single landmass before breaking apart and drifting to their present locations was fully formulated by Alfred Wegener in 1912.[2] Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas:[3][4] Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890),[5] Roberto Mantovani (between 1889 and 1909), William Henry Pickering (1907)[6] and Frank Bursley Taylor (1908).

For example: the similarity of southern continent geological formations had led Roberto Mantovani to conjecture in 1889 and 1909 that all the continents had once been joined into a supercontinent (now known as Pangaea); Wegener noted the similarity of Mantovani's and his own maps of the former positions of the southern continents. Through volcanic activity due to thermal expansion this continent broke and the new continents drifted away from each other because of further expansion of the rip-zones, where the oceans now lie. This led Mantovani to propose an Expanding Earth theory which has since been shown to be incorrect.[7][8][9]

Some sort of continental drift without expansion was proposed by Frank Bursley Taylor, who suggested in 1908 (published in 1910) that the continents were dragged towards the equator by increased lunar gravity during the Cretaceous, thus forming the Himalayas and Alps on the southern faces. Wegener said that of all those theories, Taylor's, although not fully developed, had the most similarities to his own.[10]

Wegener was the first to use the phrase "continental drift" (1912, 1915)[2][3] (in German "die Verschiebung der Kontinente" – translated into English in 1922) and formally publish the hypothesis that the continents had somehow "drifted" apart. Although he presented much evidence for continental drift, he was unable to provide a convincing explanation for the physical processes which might have caused this drift. His suggestion that the continents had been pulled apart by the centrifugal pseudoforce of the Earth's rotation was rejected as calculations showed that the force was not sufficient.[11]

Evidence that continents 'drift'

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

The notion that continents have not always been at their present positions was suggested as early as 1596 by the Dutch map maker Abraham Ortelius in the third edition of his work Thesaurus Geographicus. Ortelius suggested that the Americas, Eurasia and Africa were once joined and have since drifted apart "by earthquakes and floods", creating the modern Atlantic Ocean. For evidence, he wrote: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three continents." Francis Bacon commented on Ortelius' idea in 1620, as did Benjamin Franklin and Alexander von Humboldt in later centuries.

Evidence for continental drift is now extensive. Similar plant and animal fossils are found around different continent shores, suggesting that they were once joined. The fossils of Mesosaurus, a freshwater reptile rather like a small crocodile, found both in Brazil and South Africa, are one example; another is the discovery of fossils of the land reptile Lystrosaurus from rocks of the same age from locations in South America, Africa, and Antarctica. There is also living evidence — the same animals being found on two continents. An example of this is a particular earthworm found in South America and South Africa.

The complementary arrangement of the facing sides of South America and Africa is obvious, but is a temporary coincidence. In millions of years, seafloor spreading, continental drift, and other forces of tectonophysics will further separate and rotate those two continents. It was this temporary feature which inspired Wegener to study what he defined as continental drift, although he did not live to see his hypothesis become generally accepted.

Widespread distribution of Permo-Carboniferous glacial sediments in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, India, Antarctica and Australia was one of the major pieces of evidence for the theory of continental drift. The continuity of glaciers, inferred from oriented glacial striations and deposits called tillites, suggested the existence of the supercontinent of Gondwana, which became a central element of the concept of continental drift. Striations indicated glacial flow away from the equator and toward the poles, in modern coordinates, and supported the idea that the southern continents had previously been in dramatically different locations, as well as contiguous with each other.

Rejection of Wegener's theory

While it is now accepted that the continents do move across the Earth's surface – though more in a driven mode than the aimlessness suggested by "drift" – as a theory, continental drift was not accepted for many years. As late as 1953 – just five years before Carey[12] introduced the theory of plate tectonics – the theory of continental drift was rejected by the physicist Scheiddiger on the following grounds.[13]

First, it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes.

Second, masses floating freely in a fluid substratum, like icebergs in the ocean, should be in isostatic equilibrium (where the forces of gravity and buoyancy are in balance). Gravitational measurements were showing that many areas are not in isostatic equilibrium.

Third, there was the problem of why some parts of the Earth's surface (crust) should have solidifed while other parts are still fluid. Various attempts to explain this foundered on other difficulties.

It is now known that there are two kinds of crust, continental crust and oceanic crust, with the former of a different composition and inherently lighter, and both kinds resulting above a much deeper fluid mantle. Also, oceanic crust is still being created at spreading centers, and this, along with subduction, drives the system of plates in a chaotic manner, resulting in continuous orogeny and areas of isostatic imbalance. All this, as well as the motion of the continents, is better explained by the theory of plate tectonics.

References

- ^ Kious, W.J. (2001) [1996]. "Historical perspective". This Dynamic Earth: the Story of Plate Tectonics (Online ed.). U.S. Geological Survey. ISBN 0160482208. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origmonth=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wegener, A. (1912), "Die Entstehung der Kontinente", Peterm. Mitt.: 185–195, 253–256, 305–309

{{citation}}: line feed character in|pages=at position 9 (help) - ^ a b Wegener, A. (1929/1966), The Origin of Continents and Oceans, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0486617084

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Wegener, A. (1929), Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane, 4. Auflage, Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges.

- ^ Coxworthy, F. (1848/1924), Electrical Condition or How and Where our Earth was created, London: W. J. S. Phillips

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); External link in|title= - ^ Pickering, W.H (1907), "The Place of Origin of the Moon - The Volcani Problems", Popular Astronomy: 274–287

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ Mantovani, R. (1889), "Les fractures de l'écorce terrestre et la théorie de Laplace", Bull. Soc. Sc. Et Arts Réunion: 41–53

- ^ Mantovani, R. (1909), "L'Antarctide", Je m’instruis. La science pour tous, 38: 595–597

- ^ Scalera, G. (2003), "Roberto Mantovani an Italian defender of the continental drift and planetary expansion", in Scalera, G. and Jacob, K.-H. (ed.), Why expanding Earth? – A book in honour of O.C. Hilgenberg, Rome: Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, pp. 71–74

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Taylor, F.B. (1910), "Bearing of the tertiary mountain belt on the origin of the earth's plan", GSA Bulletin, 21 (2): 179–226, doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2005)015[29b:WTCCA]2.0.CO;2

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ Plate Tectonics: The Rocky History of an Idea

- ^ Carey, S. W. (1958), "The tectonic approach to continental dirft", in Carey, S. W. (ed.), Continental Drift—A symposium, Univ. of Tasmania, pp. 177–355

- ^ Scheidigger (1953), "Examination of the physics of theories of orogenesis", GSA Bulletin, 64: 127–150

- Le Grand, H. E. (1988). Drifting Continents and Shifting Theories. Cambridge University. ISBN 0-521-31105-5.

External links

- A brief introduction to Plate Tectonics, based on the work of Alfred Wegener.

- Maps of continental drift, from the Precambrian to the future

- Four main evidences of the Continental Drift theory

- Wegener and his proofs