Galerina marginata

| Galerina marginata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Subkingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | G. marginata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Galerina marginata | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Agaricus autumnalis Peck | |

| Galerina marginata | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is convex | |

| Hymenium is adnexed | |

| Stipe has a ring | |

| Spore print is brown | |

| Ecology is saprotrophic | |

| Edibility is deadly | |

Template:FixBunching Galerina marginata is a species of fungus in the Strophariaceae family of the Agaricales order. Prior to 2001, its synonyms G. autumnalis, G. oregonensis, G. unicolor, and G. venenata were thought to be separate species due to differences in habitat and the viscidity of their caps, but phylogenetic analysis shows that they are all the same species. Galerina marginata is widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, including Europe, North America and Asia, and has also been found in Australia. It is a wood-rotting fungus that grows predominantly on decaying conifer wood.

The fruit bodies have brown to yellow-brown caps that fade in color with moisture loss. The gills are brownish and give a rusty spore print. A well-defined membranous ring is typically seen on the stems of young specimens but often disappears with age. In older fruit bodies, the caps are flatter and the gills and stems are browner. The species are classic "little brown mushrooms"—a catchall category that includes all small to medium-sized, hard-to-identify brownish mushrooms.

Galerina marginata is extremely poisonous, and contains the same deadly amatoxins found in the death cap (Amanita phalloides). Ingestion can cause severe liver damage with vomiting, diarrhea, hypothermia, and eventual death if not treated rapidly. In the last century, about ten poisonings have been attributed to the species now grouped as G. marginata.

Taxonomy and naming

What is now recognized as the single morphologically variable taxon Galerina marginata used to be split into five distinct species. Norwegian mycologist Gro Gulden and colleagues concluded that those represented the same species after they compared the DNA sequences of the internal transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA for various North American and European specimens in Galerina section Naucoriopsis. The results showed no genetic differences between G. marginata and species formerly known as G. autumnalis, G. oregonensis, G. unicolor, and G. venenata, thus reducing all these names to synonymy.[1] The oldest of these names are Agaricus marginatus, described by August Johann Georg Karl Batsch in 1789,[2] and Agaricus unicolor, described by Martin Vahl in 1792.[3] Agaricus autumnalis was described by Charles Horton Peck in 1873, and later moved to Galerina by A. H. Smith and Rolf Singer in their 1962 worldwide monograph on that genus. In the same publication they also introduced the G. autumnalis varieties robusta and angusticystis.[4] Another synonym, G. oregonensis, was first described in that monograph. Galerina venenata was first identified as a species by Smith in 1953.[5]

Another species analysed in Gulden's 2001 study, Galerina pseudomycenopsis, was also shown to be genetically identical to G. marginata based on ribosomal DNA sequences and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Because of differences in ecology, fruit body color and spore size, in addition to inadequate taxon sampling, the authors preferred to maintain G. pseudomycenopsis as a distinct species.[1]

In the fourth edition of Singer's comprehensive classification of the Agaricales (1986), G. marginata is the type species of section Naucoriopsis, an genus subdivision first outlined by French mycologist Robert Kühner in 1935.[6] It includes includes small brown-spored mushrooms characterized by: cap edges that are initially curved inwards; fruit bodies that resemble Pholiota or Naucoria;[7] and thin-walled, obtuse or acute-ended pleurocystidia that are not rounded at the top. Within this section, G. autumnalis and G. oregonensis are in stirps Autumnalis, while G. unicolor, G. marginata, and G. venenata are in stirps Marginata. Autumnalis species are characterized by having a viscid to lubricous cap surface and Marginata species lack a gelatinous cap—the surface is moist, "fatty-shining", or matte when wet.[8] However, as Gulden explains, this characteristic is highly variable: "Viscidity is a notoriously difficult character to assess because it varies with the age of the fruitbody and the weather conditions during its development. Varying degrees of viscidity tend to be described differently and applied inconsistently by different persons applying terms such as lubricous, fatty, fatty-shiny, sticky, viscid, glutinous, or (somewhat) slimy."[1]

The common names of the species include the "marginate Pholiota" (resulting from its synonymy with Pholiota marginata),[9] "deadly skullcap", and "deadly Galerina". G. autumnalis was known as the "fall Galerina" or the "autumnal Galerina", while G. venenata was the "deadly lawn Galerina".[10][11]

Description

The cap is 17 to 40 cm (6.7 to 15.7 in) in diameter, and initially convex, sometimes with a rounded tip. The caps of young fruit bodies have edges (margins) that are curved in against the gills. As the caps grow and expand, they become broadly convex and then flattened, sometimes developing a central elevation known as an umbo, which may project prominently from the cap surface.[9]

Based on the collective descriptions of the five taxa now considered to be G. marginata, the texture of the surface shows significant variation. Smith and Singer give the following descriptions of surface texture: from "viscid" (G. autumnalis),[4] to "surface shining and viscid to lubricous when moist" (G. oregonensis),[12] to "shining, lubricous to subviscid (particles of dirt adhere to surface) or merely moist, with a fatty appearance although not distinctly viscid",[13] to "moist but not viscid" (G. marginata).[14] The smooth cap surface changes colors with humidity (hygrophanous), pale to dark ochraceous tawny over the disc, yellow-ochraceous on the margin at least when young, but fading to dull tan or darker when dry. When moist, the cap is somewhat transparent so that the outlines of the gills may be seen as striations. The flesh is pale brownish ochraceous to nearly white, thin, pliant, with an odor and taste varying from very slightly to strongly like flour (farinaceous).[14]

The gills are typically narrow and crowded together, with a broadly adnate to subdecurrent attachment to the stem. They are pallid brown when young, becoming tawny at maturity, with convex edges. Some short gills, called lamellulae, do not extend entirely from the cap edge to the stem, and are intercalated among the longer gills. The stem is 3 to 6 cm (1.2 to 2.4 in) long, 3 to 9 mm (0.12 to 0.35 in) thick at the apex, and equal in width throughout to slightly enlarged downward. The stem is initially solid but becomes hollow from the bottom up as it matures. The membranous ring is on the upper half of the stem, but may be sloughed off and missing in older specimens. Above the level of the ring, the stem surface has a very fine whitish powder and is paler than the cap; below the ring it is brown to the reddish-brown to bistre base. The lower portion of the stem has a thin coating of pallid fibrils which eventually disappear and do not leave any scales. The spore print is rusty-brown.[14]

Microscopic characteristics

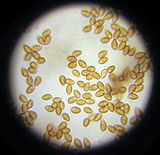

The spores measure 8–10 by 5–6 µm, and are slightly inequilateral in profile view, and egg-shaped in face view. The spore surface is warty and full of wrinkles, with a smooth depression where the spore was once attached via the sterigmatum to the spore-bearing cell, the basidium. When in potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution, the spores are tawny or darker rusty-brown, with an apical callus. The basidia are four-spored (rarely with a very few two-spored ones), roughly cylindrical when producing spores, but with a slightly tapered base, and measure 21–29 by 5–8.4 µm.[14]

Cystidia are cells of the hyphae in the fertile hymenium that do not produce basidiospores. These sterile cells, which are structurally distinct from the basidia, are further classified according to their position. In G. marginata, the pleurocystidia (cystidia present on the face of a gill) are 46–60 by 9–12 µm, fusoid-ventricose with wavy necks and obtuse (blunt) to subacute apices (3–6 µm diameter near apex), thin-walled, and hyaline in KOH. The cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill edge) are similar in shape but often smaller, abundant, with no club-shaped or abruptly tapering (mucronate) cells present. Clamp connections are present in the hyphae.[14]

Similar species

Galerina marginata may be mistaken for a few edible mushroom species. Pholiota mutabilis produces fruit bodies roughly similar in appearance that grow on wood, but may be distinguished from G. marginata by having stems with scales up to the level of the ring, and by growing in large clusters (which is not usual of G. marginata). However, the possibility of confusion is such that this good edible species is "not recommended to those lacking considerable experience in the identification of higher fungi."[15] Further, microscopic examination shows smooth spores in Pholiota.[16] G. marginata may be easily confused with such edible mushrooms as Armillaria mellea and Kuehneromyces mutabilis.[17] Regarding the latter species, one source notes "Often, G. marginata bears an astonishing resemblance to this fungus, and it requires careful and acute powers of observation to distinguish the poisonous one from the edible one."[9] K. mutabilis may be distinguished by the presence of scales on the stem below the ring, the larger cap, which may reach a diameter of 6 cm (2.4 in), and spicy or aromatic odor of the flesh. The related K. vernalis is a rare species and even more similar in appearance to G. marginata; examination of microscopic characteristics is typically required to reliably distinguish between the two.[9]

Another potential lookalike is the "velvet foot", Flammulina velutipes, an edible species. This species has gills that are white to pale yellow, a white spore print, and spores that are elliptical, smooth, and measure 6.5–9 by 2.5–4 µm.[18] A resemblance has also been noted with the edible Hypholoma capnoides,[9] as well as Conocybe filaris, another poisonous amatoxin-containing species.[19]

Habitat and distribution

Galerina marginata is typically reported to grow on or near wood of conifers, although it has been reported to grow on hardwoods as well.[1][17] The fruit bodies may grow solitarily, but more typically in groups or small clusters, and appear in the summer to autumn. Sometimes, the fruit bodies may grow on buried wood and thus appear to be growing on soil.[11] Galerina marginata is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere, being found in North America, Europe, Japan, continental Asia and the Caucasus.[14][20][21] It is also found in Australia.[22]

Toxicity

The amatoxins belong to a family of bicyclic octapeptide derivatives composed of an amino acid ring bridged by a sulphur atom and characterized by differences in their side groups; these compounds are responsible for more than 90% of fatal mushroom poisonings in humans. The amatoxins inhibit an enzyme in liver cells, called RNA polymerase II, which copies the genetic code of DNA into messenger RNA molecules. The ensuing disruption of liver cell metabolism accounts for the severe liver dysfunction cause by amatoxins. Amatoxins also lead to kidney failure because, as the kidneys attempt to filter out poison, it damages the convoluted tubules of the kidneys and reenters the blood to recirculate and cause more damage. Initial symptoms after ingestion include severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea which may last for six to nine hours. After the symptoms, toxins severely affect the liver which results in gastrointestinal bleeding, a coma, kidney failure, or even death, usually within seven days after eating.[23]

Galerina marginata was shown in various studies to contain the toxins α-amanitin and γ-amanitin, first as G. venenata,[24] then as G. marginata and G. autumnalis.[25] The ability of the fungus to produce these toxins was confirmed by growing the mycelia as a liquid culture (only trace amounts of ß-amanitin were found).[26] G. marginata is thought to be the only species of the amatoxin-producing genera that will produce the toxins while growing in culture.[27] Both amanitins were quantified in G. autumnalis (1.5 mg/g dry weight)[28] and G. marginata (1.1 mg/g dry weight).[29] Later experiments confirmed the occurrence of γ-amanitin and ß-amanitin in German basidiomes of G. autumnalis and G. marginata and revealed the presence of the three amanitins in the fruit bodies of G. unicolor.[30] Although some mushroom field guides claim that the species (as G. autumnalis) contains phallotoxins,[10][31] scientific evidence does not support this contention.[17] A 2004 study determined that the amatoxin content of G. marginata varied from 78.17 to 243.61 µg/g of fresh weight. In this study, the amanitin amounts from certain Galerina specimens were higher than those from some A. phalloides fruit bodies, a European fungus generally considered as the richest in amanitins. The authors suggest that "other parameters such as extrinsic factors (environmental conditions) and intrinsic factors (genetic properties) could contribute to the significant variance in amatoxin contents from different specimens."[17] The lethal dose of amatoxins has been estimated to be about 0.1 mg/kg human body weight, or even lower.[32] Based on this value, the ingestion of 10 G. marginata fruit bodies containing about 250 µg of amanitins per gram of fresh tissue could poison a child weighing approximately 20 kilograms (44 lb). However, a 20-year retrospective study of over 2100 cases of amatoxin poisonings from North American and Europe showed that few cases were due to ingestion of Galerina. This low frequency may be attributed to the mushroom's nondescript appearance as a "little brown mushroom" leading to it being overlooked by collectors, and by the fact that 21% of the amatoxin poisonings were caused by unidentified species.[17]

The toxicity of certain Galerina species has been known for a century. In 1912, Charles Horton Peck reported a human poisoning case due to G. autumnalis.[33] In 1954, a poisoning was caused by G. venenata.[34] Between 1978 and 1995, ten cases caused by amatoxin-containing Galerinas were reported in the literature. Three European cases, two from Finland[35] and one from France[36] were attributed to G. marginata and G. unicolor, respectively. Seven North American exposures included two fatalities from Washington due to G. venenata,[11] with five cases reacting positively to treatment; four poisonings were caused by G. autumnalis from Michigan and Kansas,[37][38] in addition to poisoning caused by an unidentified Galerina species from Ohio.[39]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Gulden G, Dunham S, Stockman J. (2001). "DNA studies in the Galerina marginata complex". Mycological Research. 105 (4): 432–40. doi:10.1017/S0953756201003707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Batsch AJGK. (1789). Elenchus fungorum. Continuatio secunda (in Latin). p. 65.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Vahl M. (1792). Flora Danica. Vol. 6. p. 7.

- ^ a b Smith and Singer, 1964, pp. 246–50.

- ^ Smith AH. (1953). "New species of Galerina from North America". Mycologia. 45 (6): 892–925. JSTOR 4547771

- ^ Kühner R. (1935). "Le Genre Galera (Fr.) Quélet". Encyclopédie Mycologique (in French). 7: 1–240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Smith and Singer, 1964, p. 235.

- ^ Singer R. (1986). The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy (4th ed.). Koenigstein: Koeltz Scientific Books. pp. 673–74. ISBN 3-87429-254-1.

- ^ a b c d e Bresinsky A, Besl H. (1989). A Colour Atlas of Poisonous Fungi: a Handbook for Pharmacists, Doctors, and Biologists. London: Manson Publishing Ltd. pp. 37–39. ISBN 0-7234-1576-5. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ a b Schalkwijk-Barendsen HME. (1991). Mushrooms of Western Canada. Edmonton: Lone Pine Publishing. p. 300. ISBN 0-919433-47-2.

- ^ a b c Ammirati JF, McKenny M, Stuntz DE. (1987). The New Savory Wild Mushroom. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 122, 128–29. ISBN 0-295-96480-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith and Singer, 1964, pp. 250–51.

- ^ Smith and Singer, 1964, pp. 256–59.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith and Singer, 1964, pp. 259–62.

- ^ Smith AH. (1975). A Field Guide to Western Mushrooms. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-472-85599-9.

- ^ Orr DB, Orr RT. (1979). Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 162–63. ISBN 0-520-03656-5.

- ^ a b c d e Enjalbert F, Cassacas G, Rapior S, Renault C, Chaumont J-P. (2004). "Amatoxins in wood-rotting Galerina marginata". Mycologia. 96 (4): 720–29. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) JSTOR 3762106 - ^ Abel D, Horn B, Kay R. (1993). A Guide to Kansas Mushrooms. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 130. ISBN 0-7006-0571-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evenson VS. (1997). Mushrooms of Colorado and the Southern Rocky Mountains. Westcliffe Publishers. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1565791923. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ Gulden G, Vesterholt J. (1999). "The genera Galerina and Phaeogalera (Basidiomycetes, Agaricales) on the Faroe Islands". Nordic Journal of Botany. 19 (6): 685–706. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.1999.tb00679.x.

- ^ Imazeki R, Otani Y, Hongo T. (1987). 日本のきのこ. Tokyo, Japan: Yamakey. ISBN 4-635-09020-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Midgley DJ, Saleeba JA, Stewart MI, Simpson AE, McGee PA. (2007). "Molecular diversity of soil basidiomycete communities in northern-central New South Wales, Australia". Mycological Research. 111 (3): 370–78. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.01.011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Russell AB. "Galerina autumnalis". Poisonous Plants of North Carolina. Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ Tyler VE, Smith AH. (1963). "Chromatographic detection of Amanita toxins in Galerina venenata". Mycologia. 55: 358–59. JSTOR 3756526

- ^ Tyler VE, Malone MH, Brady LR, Khanna JM, Benedict RG. (1963). "Chromatographic and pharmacologic evaluation of some toxic Galerina species". Lloydia. 26 (3): 154–57.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benedict RG, Tyler VE, Brady LR, Weber LJ. (1966). "Fermentative production of Amanita toxins by a strain of Galerina marginata". Journal of Bacteriology. 91 (3): 1380–81. PMC 316043.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benedict RG, Brady LR. (1967). "Further studies on fermentative production of toxic cyclopeptides by Galerina Marginata (Fr. Kühn)". Lloydia. 30: 372–78.

- ^ Johnson BEC, Preston JF, Kimbrough JW. (1976). "Quantitation of amanitins in Galerina autumnalis". Mycologia. 68 (6): 1248–53. PMID 796725.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) JSTOR 3758759 - ^ Andary C, Privat G, Enjalbert F, Mandrou B. (1979). "Teneur comparative en amanitines de différentes Agaricales toxiques d'Europe". Documents Mycologiques (in French). 10 (37–38): 61–68.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Besl H, Mack P, Schmid-Heckel H. (1984). "Giftpilze in den Gattungen Galerina und Lepiota". Zeitschrift für Mykologie (in German). 50: 183–93.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller HR, Miller OK. (2006). North American Mushrooms: a Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi. Guilford, Connecticut: Falcon Guide. p. 298. ISBN 0-7627-3109-5. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- ^ Wieland T. (1986). Peptides of Poisonous Amanita Mushrooms. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-16641-6.

- ^ Peck CH. (1912). "Report of the State Botanist 1911". New York State Museum Bulletin. 157: 1–139.

- ^ Grossman CM, Malbin B. (1954). "Mushroom poisoning: a review of the literature and report of two cases caused by a previously undescribed species". Annals of Internal Medicine. 40 (2): 249–59. PMID 13125209.

- ^ Elonen E, Härkönen M. (1978). "Myrkkynaapikan (Galerina marginata) aiheuttama myrkytys". Duodecim (in Finnish). 94 (17): 1050–53. PMID 688942.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Bauchet JM. (1983). "Poisoning said due to Galera unicolor". Bulletin of the British Mycological Society. 17 (1): 51.

- ^ Trestrail JH. (1991). "Mushroom poisoning case registry. North American Mycological Association Report 1989–1990". McIlvainea. 10 (1): 36–44.

- ^ Trestrail JH. (1994). "Mushroom poisoning case registry. North American Mycological Association Report 1993". McIlvainea. 11 (2): 87–95.

- ^ Trestrail JH. (1992). "Mushroom poisoning case registry. North American Mycological Association Report 1991". McIlvainea. 10 (2): 51–59.

Cited books

- Smith AH, Singer R. (1964). A Monograph of the Genus Galerina. New York: Hafner Publishing Co.