Mary Anning

Mary Anning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 21, 1799 Lyme Regis, England |

| Died | March 9, 1847 (aged 47) Lyme Regis, England |

| Occupation(s) | Fossil collector and paleontologist |

| Parent(s) | Richard and Mary Anning |

Mary Anning (May 21, 1799 – March 9, 1847) was an early 19th-century British fossil collector, dealer and palaeontologist. Due to her skill in locating and preparing fossils, as well as the richness of the Jurassic era marine fossil beds at Lyme Regis where she lived, she made a number of important finds. These included the first ichthyosaur skeleton to be correctly identified, the first two plesiosaur skeletons ever found, the first pterosaur skeleton located outside of Germany, and some important fish fossils. Her observations played a key role in the discoveries that belemnite fossils contained fossilized ink sacs, and that coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were fossilized faeces. When the geologist Henry De la Beche painted Duria Antiquior, the first scene out of deep time to be widely circulated, he based it largely on fossils Anning had found and he sold prints for her benefit. Her work played a key role in the fundamental and far reaching changes that occurred during the early 19th century in scientific ideas about prehistoric life and the history of the earth.

Anning's sex and social class—her parents were poor religious dissenters (non-Anglican protestants)—prevented her from fully participating in the scientific community of early 19th century Britain, dominated as it was by wealthy Anglican gentlemen, and she did not always receive full credit for her contributions. Although she became well known in geological circles in Britain, Europe, and America, she struggled financially for much of her life.

Life and career

Childhood

She was born in the coastal southern English town of Lyme Regis in Dorset,[1] Anning's father, Richard, was a cabinet maker who supplemented his income by mining the coastal cliff-side fossil beds near Lyme Regis, and selling his finds to tourists. He moved to Lyme from Colyton in Devon and married Mary Moore, known as Molly, on 8 August 1793 in Blandford. Returning to Lyme, the couple lived in a house built on the town’s bridge, and attended the local Congregational Church where their children were baptised. As religious dissenters, the Annings faced legal and social discrimination. Soon after their marriage a daughter Mary was born. She was followed by a second daughter, Martha, who died almost at once, then by a son Joseph, in 1796. In 1798 a second son, Henry, died in infancy and the eldest child, Mary, was burned to death, possibly while trying to feed wood shavings into a fire. When another daughter was born the following May, she was given the name of her dead sister, Mary.[2]

In 1800, when she was 15 months old, an extraordinary event occurred. Anning was being held by a neighbour, Elizabeth Haskings, who was standing with two friends under an elm tree watching an outdoor show, when lightning struck the tree. The three women were killed, but onlookers realised the infant was still alive and rushed her home. A local doctor called her survival miraculous, and for years afterwards members of her community would attribute the child's curiosity, intelligence, and lively personality to the incident.[2]

The Annings had at least four more children: Henry, 1801; Percival, 1803; Elizabeth, 1804; and Richard, 1809. All died within a couple of years of birth, leaving only two surviving children, Joseph and Mary. When Richard Anning died in 1810 at age 44, probably of tuberculosis, the Anning family was left without support, and had to apply for parish relief. Both Mary and her brother Joseph had accompanied their father on occasions when he searched the nearby cliffs for fossils to sell, and after his death they began collecting fossils full-time in an effort to earn some income.[2]

Fossils as a family business

Fossil collecting was in vogue in the late 18th and early 19th century, at first as a pastime akin to stamp collecting but gradually transforming into a science as the importance of fossils to geology and biology was understood. At the same time, increasing numbers of wealthy and middle class tourists were visiting Lyme Regis, which had become a popular seaside resort. As their father had before them, Mary and Joseph Anning set up a table of curiosities near the coach stop at a local inn to sell their wares to tourists. After Joseph made an important find of an ichthyosaur skull in 1810 and Mary found the associated skeleton a year later, they forged relationships within the scientific community whose passion for fossils grew to be a major source of income for the family.[3]

In 1818 Anning came to the attention of Thomas Birch, a wealthy fossil collector, when she sold him another ichthyosaur skeleton. A year later, disturbed by the poverty of the Anning family, which was at the point of having to sell their furniture to make ends meet, Birch arranged for the sale by auction of his own fossil collection, and the proceeds (some £400) were given to the Annings. Besides providing much needed funds, the public auction raised the profile of the Anning family in the geologic community. Now on a sure (if somewhat austere) financial footing for the first time in a decade, Anning carried on with her fossil collecting and selling, even as her brother began devoting more time to his new career as an apprentice upholsterer.[3] Her primary stock in trade were invertebrate fossils such as ammonite and belemnite shells, which were common in the area and sold for a few shillings. Vertebrate fossils were much rarer, and exceptional specimens like an almost complete ichthyosaur skeleton could sell for several pounds.[4] The source of all these fossils were the coastal cliffs that surround Lyme and that are part of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias. This formation consists of alternating layers of limestone and shale, laid down as sediment on a shallow seabed early in what would come to be called the Jurassic period (about 210-195 million years ago), and the cliffs are one of the richest fossil locations in Britain.[5] The cliffs could be dangerously unstable, especially in winter when rain sometimes caused landslides that often drew collectors like the Annings because they exposed new fossils. On one occasion, Anning barely avoided being killed by a landslide that did kill her dog, Tray, for years her companion while she collected.[4] An 1823 article in the Bristol Mirror written about the acquisition of an ichthyosaur skeleton found by Anning for the soon to be opened Bristol Institute included the following account of her work:

This persevering female has for years gone daily in search of fossil remains of importance at every tide, for many miles under the hanging cliffs at Lyme, whose fallen masses are her immediate object, as they alone contain these valuable relics of a former world, which must be snatched at the moment of their fall, at the continual risk of being crushed by the half suspended fragments they leave behind, or be left to be destroyed by the returning tide:– to her exertions we owe nearly all the fine specimens of Ichthyosauri of the great collections ...[6]

Fossil shop and growing expertise

As Mary Anning continued to make important finds her reputation grew. In 1826, at the age of 27, she managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store front window for her shop called Anning's Fossil Depot. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop currently had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and even America visited Anning at Lyme to purchase specimens. These included the geologist George William Featherstonhaugh who purchased fossils for the newly opened New York Lyceum of Natural History in 1827.[7] King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony visited her shop in 1844 and purchased an ichthyosaur skeleton for his extensive natural history collection. When the King's physician and aide, Carl Gustav Carus, asked Anning to write her name in his notebook she did so and beside her name she wrote "I am well known throughout the whole of Europe." Carus recorded this description of her shop in his journal: "... a shop in which the most remarkable petrifications and fossil remains — the head of an icthyosaurus, beautiful ammonites, etc. were exhibited in the window. We entered and found a little shop and adjoining chamber completely filled with fossil productions of the coast."[8]

Anning's education was extremely limited; she had learned to read at a Sunday school run by the Congregational church, and much of her childhood reading material consisted of Dissenter religious writings.[9] However, in order to educate herself as much as possible about fossils, Mary read as much of the scientific literature as she could obtain. Often she laboriously hand copied papers borrowed from others. One historian who had examined a copy she made of a 1824 paper by William Conybeare on marine reptile fossils noted that the copy included several pages of detailed technical illustrations that he was hard pressed to tell apart from the original. She also dissected modern animals including both fish and cuttlefish in order to better understand the anatomy of some of the fossils with which she was working. Lady Harriet Silvester visited Lyme in 1824.[4] She remarked in her diary:

... the extraordinary thing in this young woman is that she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved. . . It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour – that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.[10]

As time passed, her confidence in her knowledge increased, and in 1839 she took the time to write the Magazine of Natural History to question their claim that a fossil that had recently been found of the prehistoric shark Hybodus represented a new genus, as she had discovered many years ago the existence of fossil sharks with both straight and hooked teeth.[11][12] The extract from the letter that the magazine printed would be the only thing that Anning wrote ever published in her lifetime.[6]

Interactions with the scientific community

A long with purchasing specimens, many of the leading geologists of the time visited Anning to work with her in the collection of fossils and to discuss issues of anatomy and classification. Henry De la Beche, who would become one of Britain's leading geologists, collected fossils with Anning (and sometimes with her brother Joseph as well) when they were both still teenagers.[13] William Buckland who lectured on geology at Oxford often visited Lyme on his Christmas vacations and frequently went collecting with Anning.[14] In 1839 Buckland, Conybeare, and Richard Owen visited Lyme together so that Anning could lead them all on a fossil collecting excursion.[15] She also sometimes assisted Thomas Hawkins, with his efforts to collect ichthyosaur fossils at Lyme in the 1830s. She was aware of his penchant to "enhance" the fossils he collected. She wrote: "...he is such an enthusiast that he makes things as he imagines they ought to be; and not as they are really found..."[16]. A few years later a public scandal ensued when it was discovered that Hawkins had inserted fake bones to make some of his ichthyosaur skeletons seem more complete; the fossils had later been purchased for a large sum by the government for the British Museum without the appraisers knowing about the additions.[17] The Swiss palaeontologist Louis Agassiz visited Lyme in 1834 and worked with Anning to obtain and study fish fossils found in the region. He was so impressed by the knowledge of Anning and her friend Elizabeth Philpot that he wrote in his journal: "Miss Philpot and Mary Anning have been able to show me with utter certainty which are the icthyodorulites dorsal fins of sharks that correspond to different types." He thanked both of them for their help in his monumental book, Studies of Fossil Fish.[18]

Another leading British geologist, Roderick Murchison, did some of his first field work in southwest England, including Lyme. He was accompanied by his wife Charlotte who assisted with his work. Murchison wrote that they decided Charlotte should stay behind in Lyme for a few weeks to "become a good practical fossilist, by working with the celebrated Mary Anning of that place...". Charlotte Murchison and Anning became life long friends and correspondents. Charlotte, who travelled widely and met many prominent geologists through her work with her husband, helped Anning build her network of customers throughout Europe, and Anning stayed with the Murchisons when she visited London in 1829. Anning's correspondents included Charles Lyell who wrote her to ask her opinion on how the sea was affecting the coastal cliffs around Lyme, and Adam Sedgwick, who taught geology at Cambridge (Charles Darwin being one of his students) and who was one of Anning's earliest customers. Even Gideon Mantell, discoverer of the dinosaur Iguanodon, visited her at her shop.[19]

Outsider status

As a working class woman, Anning would always be an outsider to the scientific community. At the time in Britain women were not allowed to vote (neither were working class men who were too poor to meet the property requirement), hold public office, or attend university, and the newly formed but increasingly influential Geological Society did not allow women to attend meetings as guests, let alone become members.[20] Also held against Anning was her working class background and her family's status as religious dissenters, which almost certainly subjected them to discrimination in a conservative town like Lyme Regis. In most cases, the only occupations open to lower class women at the time were farm labour, domestic service, and (increasingly) work in the newly opening factories. Although Anning knew more about fossils and geology than many of the gentlemen fossilists she sold to, it was only such gentlemen who published the scientific descriptions of the specimens she found, often neglecting to mention her name. As time passed, she became resentful of this fact.[4] Later in Anning's life, a young woman who sometimes accompanied her while she collected wrote: "She says the world has used her ill...these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal of publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages."[21]

Financial difficulties, religious conversion

By 1830, because of the difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils coupled with the long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial difficulties again. The geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on his watercolour painting Duria Antiquior portraying life in prehistoric Dorset that was largely based on fossils Anning had found. De la Beche sold copies of the print to his fellow geologists and other wealthy friends and donated the proceeds to her. It became the first such scene from deep time to be widely circulated.[22][23] In December of 1830 she finally made another major find, a skeleton of a new type of plesiosaur, that sold for £200.[24] Also around this time, Anning switched from attending the local Congregational church where she had been baptised and in which she and her family had always been active members, to the Anglican church. The switch was prompted in part by a sharp decline in the number of people attending the local Congregational Chapel that began in 1828 when its popular pastor, a fellow fossil collector and friend to Anning, left for the United States to campaign against slavery and was replaced by a less likeable individual. The greater social respectability of the established church, in which many of Anning's gentleman geologist customers like Buckland and Conybeare were ordained clergy, was also a factor in her decision. Anning, who was very religiously devout, actively supported her new church as she had her old.[25]

Anning suffered another serious financial setback in 1835 when she lost most of her life savings, about £300, in a bad investment. Concerned about her financial situation, her old friend William Buckland persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the British government to award her an annuity, known as a Civil list pension, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology. The £25 a year pension gave her a certain amount of financial security.[26]

Illness and death

In March of 1847 Anning died of breast cancer; she was 47 years old. Her work had tailed off the last couple of years of her life because of her illness. As some townspeople misinterpreted the effects of the increasing doses of laudanum she was taking for the pain, there was gossip in Lyme that she was drinking.[27] After her death her friend Henry De la Beche, now president of the Geological Society of London, wrote a eulogy he read to a meeting of the society and published in its quarterly transactions. Such eulogies were an honour normally only accorded to fellows of the society, and Anning's was the first ever given for a woman. (The society did not admit women as fellows until 1904.) The eulogy began:

I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without advertising to that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society, but one who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge of the great Enalio-Saurians, and other forms of organic life entombed in the vicinity of Lyme Regis...[28]

Some members of the society subsequently contributed to a stained-glass window to her memory that was placed the parish church of St Michael the Archangel in Lyme Regis. The inscription for the window reads: "This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning of this parish, who died 9 March AD 1847 and is erected by the vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life." The window depicts the corporal works of mercy,—feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, visiting prisoners and visiting the sick. Charles Dickens wrote an article about her life in his literary magazine All the Year Round that emphasised the difficulties she had overcome, especially the scepticism of her fellow townspeople of Lyme.[29][30] Dickens wrote: "the carpenter's daughter has won a name for herself and has deserved to win it."[31]

Major discoveries

Ichthyosaurs

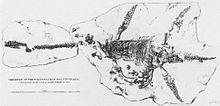

Mary Anning's first famous discovery was made shortly after her father's death when she was just twelve. In 1810 (some sources say 1811 or 1809) her brother Joseph found what he thought was a crocodile skull, but the rest of the animal was not in evidence.[6][27] Although Joseph’s time was increasingly taken up by his apprenticeship to an upholsterer, Mary kept searching and a year later a storm weathered away part of the cliff and exposed some of the rest of the skeleton of the 17ft (5.2m) long creature, which she was able to dig out of the cliff and collect with a little help from local quarrymen.[32] Other ichthyosaur remains had been discovered in years past at Lyme and elsewhere, but the specimen found by the Annings was the first to come to the attention of scientific circles in London. It was purchased for £27 in 1812 by the lord of a local manor who passed it on to William Bullock for public display in London.[6] There it created a sensation, and raised questions in scientific and even religious circles about what the new science of geology was revealing about ancient life and the history of the earth.[32] This notoriety increased when Everard Home wrote a series of six papers, starting in 1814, describing it for the Royal Society.[31][27] Home was perplexed by the creature, and kept changing his mind about its classification, first thinking it was a kind of fish, then thinking it might have some kind of affinity with the duck-billed platypus (only recently known to science); finally in 1819 he reasoned it might be a kind of intermediate form between salamanders and lizards, which lead him to propose naming it Proteo-Saurus.[33][34] Home’s papers never mentioned who had collected the fossil, and in the first one he mistakenly credited the painstaking cleaning and preparation of the fossil that Anning had performed to the staff at Bullock’s museum.[32][35] Charles Konig, then an assistant curator of the British Museum, had already suggested the name ichthyosaurus (fish lizard) for the specimen and that name stuck. Konig purchased the skeleton for the Museum in 1819.[33]

Anning found several other ichthyosaur fossils during the period of 1815–1819, including almost complete skeletons ranging in size from as small as a trout to as large as a whale. In 1821 William Conybeare and Anning’s old friend Henry De la Beche, both members of the Geological Society of London, collaborated on a paper that analysed in detail the specimens found by Anning and others. They concluded that ichthyosaurs were a previously unknown kind of marine reptile, and based on differences in tooth structure they concluded that there had been at least three species.[36][33]

Plesiosaurs

Her next major discovery was a skeleton of a new type of marine reptile in the winter of 1820–1821, the first of its kind to be found. William Conybeare named it Plesiosaurus (near lizard) because he thought it more like modern reptiles than the ichthyosaur had been, and he described it in the same 1821 paper he co-authored with Henry De la Beche on ichthyosaur anatomy. The paper thanked the man who bought the skeleton from Anning for giving Conybeare access to it, but does not mention the woman who discovered and prepared it.[37][36] The fossil was subsequently described as Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus and is the type specimen (holotype) of the species, which itself is the type species of the genus. In 1823 she discovered a second even more complete plesiosaur skeleton (the first one had been missing the skull). When Conybeare presented his analysis of plesiosaur anatomy to a meeting of the Geological Society in 1824, he again failed to mention Mary Anning by name, even though she had collected both skeletons and she had made the sketch of the second skeleton he used in his presentation. Conybeare's presentation was made at the same meeting at which William Buckland described the dinosaur Megalosaurus and the combination created a sensation in scientific circles.[38][39]

Conybeare's presentation followed the resolution of a controversy over the legitimacy of one of the fossils. The extremely long neck of the plesiosaur with its unprecedented 35 neck vertebrae had raised the suspicions of the eminent French anatomist Georges Cuvier when he reviewed Anning's drawings of the second skeleton, and he wrote to Conybeare suggesting the possibility the find was a fake produced by combining fossil bones from different kinds of animals. Fraud was far from unknown among early 19th century fossil collectors, and if the controversy had not been resolved promptly the accusation could have seriously damaged Anning's ability to sell fossils to other geologists. Cuvier's accusation had resulted in a special meeting of the Geological Society earlier in 1824, which after some debate had concluded the skeleton was legitimate. Cuvier later admitted he had acted in haste and was mistaken.[40]

Anning discovered yet another important and nearly complete plesiosaur skeleton in 1830. It was named Plesiosaurus macrocephalus by William Buckland and described in an 1840 paper by Richard Owen.[6] Once again Owen mentioned the wealthy gentleman who had purchased the fossil and made it available for examination, but not the woman who had discovered it.[41]

Fossil fish and pterosaur

Anning found an 'unrivalled specimen' of Dapedium politum, a ray-finned fish described in 1828. In December of that same year she discovered an important fossil, the partial skeleton of a pterosaur. In 1829 William Buckland described it as Pterodactylus macronyx (later renamed Dimorphodon macronyx by Richard Owen), and unlike many other such occasions, Buckland credited Anning with the discovery in his paper. It was the first pterosaur skeleton found outside Germany, and it created a public sensation when displayed at the British Museum. In December of 1829 she found a fossil fish, Squaloraja, which attracted attention because it had characteristics intermediate between sharks and rays.[6]

Invertebrates and trace fossils

Those vertebrate fossil finds made Anning's mark in history, but she continued collecting for the remainder of her life and made numerous other contributions to early paleontology. In 1826 she discovered what appeared to be a chamber containing dried ink inside a belemnite fossil. She showed it to her friend Elizabeth Philpot who was able to revivify the ink and use it to illustrate some of her own icthyosaur fossils, and other local artists were soon doing so also when such ink chambers were found in more fossils. Anning noted how closely the fossilized ink chambers resembled the ink sacs of modern squid and cuttle fish, which she had dissected to better understand the anatomy of fossil cephalopods, and this quickly led her friend the geologist William Buckland to publish the conclusion that Jurassic belemnites had used ink for defence just as many modern cephalopods do.[42] It was also Anning who noticed that the oddly shaped fossils then known as "bezoar stones" were sometimes found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons. She also noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilized fish bones and scales, and sometimes bones from small ichthyosaurs. Anning suspected the stones were fossilized faeces as early as 1824, and in 1829 William Buckland published that conclusion and named them coprolites. In contrast to the finding of the plesiosaur skeletons a few years earlier, for which she was not credited, when Buckland presented his findings on coprolites to the Geological Society he mentioned Anning by name and praised her skill and industry in helping resolve the mystery.[43][6]

Impact and legacy

Taken together, Mary Anning's discoveries became key pieces of evidence for extinction. Georges Cuvier had argued for the reality of extinction in the late 1790s based on his analysis of fossils of mammals such as mammoths. Nevertheless, until the early 1820s it was still believed by many scientifically literate people that animals did not become extinct—in part because they felt that extinction would imply that God's creation had been imperfect; any oddities found were explained away as belonging to animals still living somewhere in an unexplored region of the earth. The bizarre nature of the fossils found by Anning, some like the plesiosaur so unlike any known living creature, struck a major blow against this idea.[44]

The ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaur she found, along with the first dinosaur fossils which were discovered by Gideon Mantell and William Buckland during the same period, showed that during previous eras the earth was inhabited by creatures very different from those living today, and provided important support for another controversial suggestion of Cuvier's: that there had been an "age of reptiles" when reptiles rather than mammals had been the dominant form of animal life. These discoveries also played a key role in the development in the 1820s of a new discipline of geohistorical analysis within geology that sought to understand the history of the earth by using evidence from fossils to reconstruct extinct organisms and the environments they lived in; this discipline eventually came to be called palaeontology.[46] The illustrations of scenes from deep time like Henry De la Beche's ground breaking painting Duria Antiquior, helped convince people that it was possible to understand life in the distant past. De la Beche had been inspired to create the painting by a vivid description of the food chain of the lias by William Buckland based on analysis of coprolites. The study of coprolites, pioneered by Buckland and Anning, would prove to be a valuable tool for understanding ancient ecosystems.[45]

After her death, Anning's unusual life continued to attract attention. It is well known that Mary Anning is associated with the old tongue-twister, "She sells sea shells on the sea shore." [47] It was composed in 1908, more than a half century after her death, by Terry Sullivan who was inspired by her life story.[48] The original text was:

She sells seashells on the seashore

The shells she sells are seashells, I'm sure

So if she sells seashells on the seashore

Then I'm sure she sells seashore shells.[48]

Anning's life story was seen as inspirational by a number of writers who throughout the 20th century, starting with The Heroine of Lyme Regis: The Story of Mary Anning the Celebrated Geologist (1925), published various works of fiction and non-fiction about her. The majority of this material was intended as inspirational literature for children, and tended to focus on her childhood and early career, neglecting her later accomplishments. Much of it was also highly romanticized and not always historically accurate. She has appeared as a character in historical novels, perhaps most notably in The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969) by John Fowles, which was made into a feature film in 1981. Fowles observed critically that no British scientist had named a species after Anning in her lifetime.[6] As one of her biographers noted, this contrasted with the fact that some of the prominent gentleman geologists who had utilized her finds, like Buckland and Roderick Murchison, ended up with multiple fossil species named after them. However, in the 1840s the Swiss-American expert on fossil fish Louis Agassiz did name two fossil fish species, Acrodus anningiae, and Belenostomus anningiae, after her, and another after her friend Elizabeth Philpot. Agassiz was grateful for the help the two women had given him in examining and understanding fossil fish specimens, during his 1834 visit to Lyme Regis. [18]

In 1999, on the 200th anniversary of her birth, an international meeting of historians, palaeontologists, fossil collectors and others interested in Mary Anning's life was held in Lime Regis.[49] In 2005, a Mary Anning 'facsimile' was created at the Natural History Museum as one of a number of notable gallery characters to patrol its displays. She is thus among other luminaries including Carl Linnaeus, Dorothea Bate, and William Smith.[50] In 2009 Tracy Chevalier wrote a historical novel entitled Remarkable Creatures, which charts Anning's life and discoveries as well as that of Elizabeth Philpot.[51]

Notes

- ^ Blue plaque marking Mary Anning's birthplace.

- ^ a b c Emling 2009, pp. 1–22

- ^ a b Emling 2009, pp. 31–35

- ^ a b c d McGowan 2001, pp. 14–21

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 11–12

- ^ a b c d e f g h Torrens 1995

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 97–103

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 190–192

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 26

- ^ "Mary Anning". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 172

- ^ Anning, Mary (1839). "Extract of a letter from Miss Anning". The Magazine of natural history and journal of zoology, botany, Volume 3.

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 35

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 26–27

Emling 2009, pp. 53–56 - ^ Emling 2009, pp. 173–176

- ^ McGowan 2001, p. 131

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 133–148

- ^ a b Emling 2009, pp. 169–170

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 99–101, 124–125, 171

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 40

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 203–204

- ^ Rudwick 1992, pp. 42–47

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 139–143

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 143

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 144–145

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 171–172

- ^ a b c "Mary Anning". The Dorset Page. Retrieved 2010-1-1.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Emling 2009, p. 199

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 193–198

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 200–201

- ^ a b "Mary Anning". Strange Science: The Rocky Road to Modern Paleontology and Biology. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ^ a b c Emling 2009, pp. 33–41

- ^ a b c Rudwick 2008, pp. 26–30

- ^ Home 1819

- ^ Home 1814

- ^ a b De la Beche & Conybeare 1821

- ^ McGowan 2001, pp. 23–26

- ^ McGowan 2001, p. 75

- ^ Conybeare 1824

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 81–83

- ^ Emling 2009, p. 143

- ^ McGowen 2001, p. 20

Emling 2009, p. 109 - ^ Rudwick 2008, pp. 154–155

- ^ Emling 2009, pp. 48–50, 88

- ^ a b Rudwick 2008, pp. 154–158

- ^ Rudwick 2008, pp. 57–58, 72

- ^ Mary Anning – Natural History Museum

- ^ a b Emling 2009, pp. xi, 198

- ^ McGowan 2001, p. 203

- ^ Russell, Miles. "Review of Discovering Dorthea". The Prehistoric Society. Retrieved 03-03-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Chevalier, Tracy. "Remarkable Creatures". Waterstone's Books Quarterly. Retrieved 2010-2-5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

References

- Anonymous (1828), Another discovery by Mary Anning of Lyme. An unrivalled specimen of Dapedium politum an antediluvian fish, vol. 108:5599, Salisbury and Winchester Journal, p. 2

- Conybeare, William (1824), On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus, Geological Society of London, retrieved 2010-1-15

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - De la Beche, Henry; Conybeare, William (1821), Notice of the discovery of a new Fossil Animal, forming a link between the Ichthyosaurus and Crocodile, together -with general remarks on the Osteology of the Ichthyosaurus, Geological Society of London, retrieved 2010-1-10

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Emling, Shelley (2009), The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman whose Discoveries Changed the World, Palgrove Macmillan, ISBN 978-0230611566

- Home, Everard (1814), Some Account of the Fossil Remains of an Animal More Nearly Allied to Fishes Than Any of the Other Classes of Animals, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, retrieved 2010-1-24

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Home, Everard (1819), Reasons for Giving the Name Proteo-Saurus to the Fossil Skeleton Which Has Been Described, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, retrieved 2010-1-31

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - McGowan, Christopher (2001), The Dragon Seekers, Persus Publishing, ISBN 0-7382-0282-7

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (1992), Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-73105-7

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (2008), Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-73128-6

- Torrens, Hugh (1995), Mary Anning (1799–1847) of Lyme: 'the greatest fossilist the world ever knew' (subscription required for full text), vol. 25, Journal for the History of Science, pp. 257–284

See also

- Jurassic Coast

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- History of paleontology

Further reading

- Anholt, Laurence (2006), Stone Girl Bone Girl: The Story of Mary Anning, Frances Lincoln Publishers, ISBN 1-84507-700-8

- Atkins, Jeannine (1999), Mary Anning and the Sea Dragon, Farrar Straus Giroux, ISBN 978-0374348403

- Brown, Don (2003), Rare Treasure: Mary Anning and Her Remarkable Discoveries, Houghton Mifflin Co, ISBN 0-618-31081-9

- Chevalier, Tracy (2010), Remarkable Creatures, Dutton, ISBN 978-1-101-15245-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|authorling=ignored (help) - Clarke, Nigel J. (1998), Mary Anning 1799–1847: A Brief History, Clarke (Nigel J) Publications, ISBN 0-907683-57-6

- Cole, Sheila (2005), The Dragon in the Cliff: A Novel Based on the Life of Mary Anning, iUniverse.com, ISBN 0-595-35074-7

- Day, Marie (1995), Dragon in the Rocks: A Story Based on the Childhood of the Early Paleontologist, Mary Anning, Maple Tree Press, ISBN 1-895688-38-8

- Fradin, Dennis B. (1997), Mary Anning: The Fossil Hunter (Remarkable Children), Silver Burdett Press, ISBN 0-382-39487-9

- Goodhue, Thomas W. (2002), Curious Bones: Mary Anning and the Birth of Paleontology (Great Scientists), ISBN 1-883846-93-5

- Goodhue, Thomas W. (2004), Fossil Hunter: The Life and Times of Mary Anning (1799–1847), Academica Pr Llc, ISBN 1-930901-55-0

- Goodhue, Thomas W (2005), "Mary Anning: the fossilist as exegete", Endeavour, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 28–32, doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2004.11.004, PMID 15749150

- Norman, DB (1999), "Mary Anning and her times: the discovery of British palaeontology (1820–1850).", Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.), vol. 14, no. 11 (published 1999 Nov), pp. 420–421, doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01700-0, PMID 10511714

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) - Pierce, Patricia (2006), Jurassic Mary: Mary Anning and the Primeval Monsters, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-4039-5

- Tickell, Crispin (1996), Mary Anning of Lyme Regis, Lyme Regis Philpot Museum, ISBN 0-9527662-0-5

- Walker, Sally M. (2000), Mary Anning: Fossil Hunter (On My Own Biographies (Hardcover)), Carolrhoda Books, ISBN 1-57505-425-6

External links

- Mary Anning, Finder of Fossils at the San Diego Supercomputer Center site on women scientists.

- Mary Anning at the Lyme Regis museum

- Article on Anning at the UC Berkely Museum of Paleontology

- Article on Anning at The Dorset Page

- Biography of Anning at the British Natural History Museum

- Article on Anning at strange science

- A 360 degree panorama of East Cliff at Lyme Regis, the site of Mary Anning's ichthyosaur find in 1811

- song “Mary Anning” by "Artichoke"