Opsikion

| Theme of Opsikion Ὀψίκιον, θέμα Ὀψικίου | |

|---|---|

| Theme of the Byzantine Empire | |

| 7th century – 1230s | |

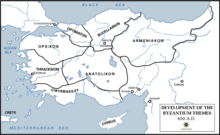

The Asian themes of the Byzantine Empire ca. 780. | |

| Capital | Ancyra, then Nicaea |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

• Established | the 7th century |

• Disestablished | 1234 |

The Opsician Theme (θέμα Ὀψικίου, thema Opsikiou) or simply Opsikion ([θέμα] Ὀψίκιον, Latin: Obsequium) was a Byzantine theme (a military-civilian province) in northwestern Asia Minor (modern Turkey). Created from the imperial retinue army, the Opsikion was the largest and most prestigious of the early themes, being located closest to Constantinople. Involved in several revolts in the 8th century, it was split in three after ca. 750, and lost its former preeminence. It survived as a middle-tier theme until after the Fourth Crusade.

History

The Opsician theme was one of the first four themes, and has its origin in the praesental armies[a] of the East Roman army. The term Opsikion derives from the Latin Obsequium ("retinue"), which by the early 7th century came to refer to the unit responsible for escorting the emperor on campaign.[1] It is possible that at an early stage, the unit was garrisoned inside Constantinople itself.[2] In the 640s however, following the disastrous defeats suffered during the first wave of the Muslim conquests, the remains of the field armies were withdrawn to Asia Minor and settled into large districts, called themes (themata).[3] Thus the Opsician theme was the area where the imperial Opsikion was settled, which encompassed all of north-western Asia Minor (Mysia, Bithynia, parts of Galatia. Lydia and Paphlagonia) from the Dardanelles to the Halys River, with Ancyra as its capital. The exact date of the theme's establishment is unknown; the earliest reference point to a creation as early as 626, but the first confirmed occurence is in 680.[4][5][6] It is possible that it initially included also the area of Thrace, which seems to have been administered jointly with Opsikion in the late 7th and early 8th centuries.[4][7]

The unique origin of the Opsikion was also reflected in several aspects of the theme's organization. Thus the title of its commander was not στρατηγός (stratēgos, "General") as with the other themes, but κόμης (komēs, "Count"), in full κόμης τοῦ βασιλικοῦ Ὀψικίου (komēs tou basilikou Opsikiou, "Count of the imperial Opsikion"),[4] Furthermore, it was not divided into tourmai, but into domesticates formed from the elite corps of the army, such as the Optimatoi and Boukellarioi, both terms dating back to the recruitment of Gothic foederati in the 4th–6th centuries.[8] Its prestige is further illustrated by the seals of its commanders, where it is called the "God-guarded imperial Opsikion" (θεοφύλακτον βασιλικόν ὀψίκιον, in Latin a Deo conservandum imperiale Obsequium).[6]

Being the theme closest to the imperial capital Constantinople and enjoying a position of pre-eminence among the other themes, the counts of the Opsikion were often tempted to revolt against the emperors. Already in 668, on the death of Constans II in Sicily, the count Mezezius staged an abortive coup.[9] Under the patrikios Barasbakourios, the Opsikion was the main powerbase of Emperor Justinian II (r. 685–695 and 705–711).[6] Justinian also settled many Slavs captured in Thrace there, in an attempt to boost its military strength. Most of them however deserted to the Arabs on the first battle.[10] In 713, the Opsikian army overthrew Philippikos Bardanes (r. 711–713), the man who overthrew and murdered Justinian, and enthroned Anastasios II (r. 713–715), only to overthrow him too in 715 and install Theodosios III (r. 715–717) in his place.[11][12] In 716, the Opsicians supported the rise of Leo III the Isaurian (r. 716–740) to the throne, but in 718, their count, the patrikios Isoes rose up unsuccessfully against him.[6] In 741–742, the kouropalatēs Artabasdos used it as a base for his brief usurpation of Constantine V (r. 741–775). In 766, another count was blinded after a failed mutiny against the same emperor.[5] In this period, the revolts of the Opsician theme also the Opsikians were staunchly iconodule, and opposed to the iconoclast policies of the Isaurian emperors.[13] As a result, Constantine V set out to weaken the power of the theme: the new themes of the Boukellarioi and the Optimatoi were split off.[14][15] At the same time, the emperor recruited a new set of elite and staunchly iconoclast guard regiments, the tagmata.[14][16]

Consequently, the reduced Opsikion was downgraded from a guard formation to an ordinary cavalry theme: its forces were divided into tourmai, and its komēs fell to the sixth place in the hierarchy of thematic governors and was even renamed to the "ordinary" title of stratēgos by the end of the 9th century.[6][17][18] In the 9th century, he is recorded as receiving an annual salary of 30 pounds of gold, and of commanding 6,000 men (down from some 18,000 of the old Opsikion).[17][19] The thematic capital was moved to Nicaea, and Constantine Porphyrogennetos, in his De Thematibus, mentions further nine cities in the theme: Cotyaeum, Dorylaeum, Midaion, Apamea, Myrleia, Lampsacus, Parion, Cyzicus and Abydus.[6]

In the great revolt of Thomas the Slav in the early 820s, the Opsikion remained loyal to Michael II (r. 820–829).[20] In 866, the Opsician stratēgos, George Peganes, rose up along with the Thracesian Theme against Basil I the Macedonian (r. 867–886), then the co-emperor of Michael III (r. 842–867), and in ca. 930, Basil Chalkocheir revolted against Romanos I Lekapenos (r. 920–944). Both revolts however were easily quelled, and are a far cry from the emperor-making revolts of the 8th century.[6] The theme survived through the Komnenian period,[21] and apparently also into the Empire of Nicaea: George Akropolites records that in 1234, the Opsician theme fell under the "Italians" (i.e. the Latin Empire).[6][17]

References

Footnotes

^ a: The praesental armies were the forces commanded by the two magistri militum praesentalis, the "masters of the soldiers in the presence [of the emperor]". They were stationed around Constantinople in Thrace and Bithynia, and formed the core of the various imperial expeditions in the 6th and early 7th centuries.

Citations

- ^ Haldon (1984), pp. 443–444

- ^ Haldon (1984), p. 178

- ^ Haldon (1997), pp. 214–216

- ^ a b c Treadgold (1998), p. 23

- ^ a b Kazhdan (1991), p. 1528

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lambakis (2003)

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), p. 2079

- ^ Lounghis (1996), pp. 28–32

- ^ Haldon (1997), p. 313

- ^ Treadgold (1998), p. 26

- ^ Treadgold (1998), p. 27

- ^ Haldon (1997), pp. 80, 442

- ^ Lounghis (1996), pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Lounghis (1996), pp. 28–31

- ^ Treadgold (1998), pp. 29, 71

- ^ Treadgold (1998), pp. 71, 99, 210

- ^ a b c Kazhdan (1991), p. 1529

- ^ Lounghis (1996), p. 30

- ^ Haldon (1999), p. 314

- ^ Treadgold (1998), p. 31

- ^ Haldon (1999), p. 97

Sources

- Haldon, John F. (1984). Byzantine Praetorians. An Administrative, Institutional and Social Survey of the Opsikion and Tagmata, c. 580-900. R. Habelt. ISBN 3774920044.

- Haldon, John F. (1997). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521319171.

- Haldon, John F. (1999). Warfare, state and society in the Byzantine world, 565-1204. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-494-1.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Lambakis, Stylianos (2003-10-17). "Οψικίου Θέμα" (in Greek). Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Lounghis, T.K. (1996), "The Decline of the Opsikian Domesticates and the Rise of the Domesticate of the Scholae", Byzantine Symmeikta (10): 27–36, ISSN 1105-1639

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1998). Byzantium and Its Army, 284-1081. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804731632.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help)