Ratha

Ratha ( Sanskrit rátha, Avestan raθa) is the Indo-Iranian term for the spoked-wheel chariot of Antiquity. It derives from a collective *ret-h- to a Proto-Indo-European word *rot-o- for "wheel" that also resulted in Latin rota and is also known from Germanic, Celtic and Baltic. The Sanskrit terms for the wagon pole, harness, yoke and wheel have cognates in other branches of Indo-European.

Proto-Indo-Iranians

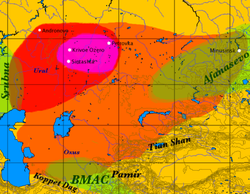

Development of the spoke-wheeled chariot is associated with the Proto-Indo-Iranians. The earliest fully developed chariots known are from the chariot burials of the Andronovo (Timber-Grave) sites of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia and Kazakhstan from around 2000 BC. This culture is at least partially derived from the earlier Yamna culture. It built heavily fortified settlements, engaged in bronze metallurgy on a scale hitherto unprecedented and practiced complex burial rituals, according to some scholars [who?] reminiscent of Aryan rituals known from the Rigveda. The Sintashta-Petrovka chariot burials yield spoke-wheeled chariots. The Andronovo culture over the next few centuries spreads across the steppes from the Urals to the Tien Shan, likely corresponding to early Indo-Iranian cultures which eventually spread to Iran and India in the course of the 2nd millennium BC.

The chariot must not necessarily be regarded as a marker for Indo-European or Indo-Iranian presence.[1] According to Raulwing, it is an undeniable fact that only comparative Indo-European linguistics is able to furnish the methodological basics of the hypothesis of a "PIE chariot", in other words: "Ausserhalb der Sprachwissenschaft winkt keine Rettung![2]"[3][4]

The earliest evidence for chariots in southern Central Asia (on the Oxus) dates to the Achaemenid period (apart from chariots harnessed by oxen, as seen on petroglyphs).[5] No Andronovian chariot burial has been found south of the Oxus.[6]

No evidence of spoke-wheeled vehicles predating 2000 BC is known from either inside or outside of India. But according to Dr.Syed Zakir Hussain Zazu it existed well beyond 2100 BC and there are archeological evidence on that.[citation needed]

Remains

There are a few depictions of chariots among the petroglyphs in the sandstone of the Vindhya range. Two depictions of chariots are found in Morhana Pahar, Mirzapur district. One shows a team of two horses, with the head of a single driver visible. The other one is drawn by four horses, has six-spoked wheels, and shows a driver standing up in a large chariot-box. This chariot is being attacked, with a figure wielding a shield and a mace standing at its path, and another figure armed with bow and arrow threatening its right flank. It has been suggested (Sparreboom 1985:87) that the drawings record a story, most probably dating to the early centuries BC, from some center in the area of the Ganges–Jamuna plain into the territory of still neolithic hunting tribes. The drawings would then be a representation of foreign technology, comparable to the Arnhem Land Aboriginal rock paintings depicting Westerners. The very realistic chariots carved into the Sanchi stupas are dated to roughly the 1st century.

The earliest chariot remains that have been found in India (at Atranjikhera) has been dated to between 350 and 50 BCE [7]. It is also highly unlikely that a perishable item like the chariot could have been preserved in the Indian climate since Harappan times [8]. There is evidence of wheeled vehicles (especially miniature models) in the Indus Valley Civilization, but not of chariots.[9]

Indus valley sites have offered several instances of evidence of spoked wheels. Prof. B.B.Lal[10] has irrevocably proved with convincing specimens the existence and use of spoked wheel chariots in Harappan Civilization. Bhirrana excavations 2005-06[11]. Bhagwan Singh[12] had made a similar assertion and S.R.Rao had had presented evidence of chariots in bronze models from Diamabad (Late Harappan). This aspect appears to have been overlooked.

Textual evidence

Chariots are also an important part of Hindu as well as of Persian mythology, with most of the gods in their pantheon portrayed as riding them.

Chariots figure prominently in the Rigveda, evidencing their presence in India in the 2nd millennium BC. Among Rigvedic deities, notably Ushas (the dawn) rides in a chariot, as well as Agni in his function as a messenger between gods and men.

The Rigvedic chariots are described as made of Salmali (RV 10.85.20), Khadira and Simsapa (RV 3.53.19).

In RV 6.61.13, the Sarasvati river is described as being big like a chariotof the Rigvedic chariot . Measurements for the chariot are found in the Sulba Sutras. The number of wheels varies. A similar term in the Rigveda is Anas (often translated as "cart").[13]

In Hindu temple festivals

Ratha or Rath means a chariot or car made from wood with wheels. The Ratha may be driven manually by rope, pulled by horses or elephants. Rathas are used mostly by the Hindu temples of South India for Rathoutsava (Car festival). During the festival, the temple deities are driven through the streets, accompanied by the chanting of mantra, hymns, shloka or bhajan.

Notes

- ^ Cf. Raulwing 2000

- ^ Outside of linguistics there's no hope.

- ^ Raulwing 2000:83

- ^ Cf. Henri Paul Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p. 272-276

- ^ They were not used for warfare. H. P. Francfort, Fouilles de Shortugai, Recherches sur L'Asie Centrale Protohistorique Paris: Diffusion de Boccard, 1989, p. 452. Cf. Henri Paul Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p.272

- ^ H. P. Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p. 220, 272; H.-P. Francfort, Fouilles de Shortugai

- ^ (Bryant 2001)

- ^ cf. Bryant 2001 (The earliest known chariots in Sintashta were found in chariot burials (which are not common in India), and the chariots themselves have rotted away.)

- ^ Bryant 2001

- ^ The Sarasvati Flows on, 2002, pp.74-75, Figs 3.28 to 331

- ^ L.S.Rao, Harappan Spoked Wheels Rattled Down the Streets of Bhirrana, Dist. Fatehabad, Haryana

- ^ Harappan Civilization and the Vedic Literature, in Hindi, 1987

- ^ A discussion of the difference between ratha and anas is found e.g. in Kazanas, Nicholas. 2001. The AIT and Scholarship

References

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X.: Aryas, Aryens et Iraniens en Asie Centrale. (2005) Institut Civilisation Indienne ISBN 2-86803-072-6

- Kazanas, Nicholas. The AIT and Scholarship. Athens, 2001.

- Peter Raulwing, Horses, Chariots and Indo-Europeans, Foundations and Methods of Chariotry Research from the Viewpoint of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Archaeolingua, Series Minor 13, Budapest 2000)