Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T or KT) extinction event, also known as the KT boundary, was a period of massive extinction of species, about 65.5 million years ago. It corresponds to the end of the Cretaceous Period and the beginning of the Tertiary Period. (K is the traditional abbreviation for the Cretaceous period. Cretaceous comes from the Latin for chalk, creta. The K comes from the German word for chalk kreide, or possibly Greek kreta. The K is used so as to avoid confusion with the Carboniferous period which uses the letter C.)

The duration of this extinction event (like others) is unknown. Many forms of life perished (embracing approximately 50% of all genera), the most often mentioned among them being the non-avian dinosaurs. Many explanations for this event have been proposed, the most widely-accepted being the results of an impact on the Earth of an object from space.

Casualties of the extinction

A wide range of organisms became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period. The most conspicuous, of course, were the dinosaurs. While there is evidence that dinosaur diversity declined in the Late Cretaceous of North America, many species are known from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations of the Late Cretaceous. These include six or seven families of theropods and a similar number of ornithischians. Among the Dinosauria, the only survivors were the birds, but birds suffered heavy losses. A number of diverse groups became extinct, including the Enantiornithes and Hesperornithiformes; the last of the pterosaurs also went extinct. A number of mammal groups also became extinct. In the sea, many species of phytoplankton were wiped out. The great sea reptiles of the Cretaceous, the mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, also fell victim to extinction. Among mollusks, the ammonites, a diverse group of coiled cephalopods, were exterminated, as were the specialized rudist and inoceramid clams. Freshwater mussels and snails also suffered heavy losses in North America. Much less is known about how the K-T event affected the rest of the world. It should be emphasized that the survival of a group does not mean that the group was unaffected: a species may be 99% annihilated by an asteroid strike, yet still manage to survive.

Darkness from an impact-generated dust cloud (Alvarez et al. 1980) may have been supplemented by associated gases.

Darkness resulted in loss of photosynthesis both on land and in the oceans. On land preferential survival may be closely tied to animals that were not in food chains directly dependent on plants. Dinosaurs (both herbivores and carnivores) were in plant eating food chains.

Mammals of the Late Cretaceous were not herbivores. Many mammals fed on insects, larvae, worms, snails etc., which in turn fed on dead plant matter. During the crisis when green plants disappeared, mammals may have survived, because they lived in “detritus based” food chains. Soon after the K/T extinction the mammals radiated into plant eating lifestyles, and were soon followed by other mammals that became carnivores.

In stream communities few groups of animals became extinct. Stream communities tend to be less reliant on food from living plants and are more dependent on detritus that washes in from land. The stream communities may also have been buffered from extinction by their reliance on detritus-based food chains. (See Sheehan and Fastovsky, Geology, v. 20, p. 556-560.) Similar, but more complex patterns have been found in the oceans. For example, animals living in the water column are almost entirely dependent on primary production from living phytoplankton. Many animals living on or in the ocean floor feed on detritus, or at least can switch to detritus feeding. Extinction was more severe among those animals living in the water column than among animals living on or in the sea floor.

Theories

Alvarez hypothesis

In 1980, a team of researchers led by Nobel-prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez, his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, and a group of colleagues discovered that fossilized sedimentary layers found all over the world at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary, 65.5 million years ago contain a concentration of iridium hundreds of times greater than normal. The end of the Cretaceous coincided with the end of the dinosaurs. It was in general a period of extraordinary mass extinction, leading to the Tertiary Period of the Cenozoic Era, in which mammals came to dominate on Earth. The paper suggested that the dinosaurs had been killed off by the impact of a ten-kilometer-wide asteroid on Earth (see impact event). Two facts supporting this conclusion are that

- iridium is relatively abundant in many asteroids, and

- the isotopic composition of iridium in K-T layers resembles that of asteroids more closely than that of terrestrial iridium.

Iridium is very rare on Earth's surface, but much more common in the Earth's interior as well as in extraterrestrial objects, such as asteroids and comets. Furthermore, chromium isotopic anomalies are found in Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary sediments which strongly supports the impact theory and suggests that the impactor must have been an asteroid or a comet composed of material similar to carbonaceous chondrites.

The resulting blast would have been hundreds of millions of times more devastating than the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated, may have created a hurricane of unimaginable fury, and certainly would have thrown massive amounts of dust and vapor into the upper atmosphere and even into space.

A global firestorm may have resulted as the incendiary fragments from the blast fell back to Earth. Analyses of fluid inclusions in ancient amber suggest that the oxygen content of the atmosphere was very high (30 - 35%) during the late Cretaceous [1]. This high O2 atmospheric content would have supported massive combustion. The level of atmospheric O2 plummeted in the early Tertiary.

In addition, the worldwide cloud would have choked off sunlight for months, resulting in a darkness that prevented photosynthesis and depleting food resources. During this interval of reduced sunlight a "long winter" may have also been involved in the extinction. Gradually skies cleared but greenhouse gases from the impact caused an increase in temperature for many years.

The impact target rocks also produced acid rains that would have inflicted further hardship on the environment, but recent work suggests this was relatively minor. Chemical buffers would have reduced the effect, and survival of animals prone to acid rain damage (such as frogs) indicate this was not a major contributor to extinction (see Kring, D.A. GSA Today v. 10, no.8).

Although further studies of the K-T layer consistently showed the excess of iridium, the idea that the dinosaurs were exterminated by an asteroid remained a matter of controversy among geologists and paleontologists for over a decade.

Chicxulub crater

Main article: Chicxulub Crater

One problem with the "Alvarez hypothesis" (as it came to be known) was that no documented crater matched the event. This was not a lethal blow to the theory; although the crater resulting from the impact would have been 150 to 200 kilometers in diameter, Earth's geological processes tend to hide or destroy craters over time. The discovery by Alan R. Hildebrand and Glen Penfield of a crater buried under Chicxulub in the Yucatan as well as various types of debris in North America and Haiti have lent credibility to this theory (see Chicxulub Crater). Most paleontologists now agree that an asteroid did hit the Earth 65 million years ago, but many dispute whether the impact was the sole cause of the extinctions.

Deccan traps

Main article: Deccan Traps

Several paleontologists remained skeptical about the impact theory, as their reading of the fossil record suggested that the mass extinctions did not take place over a period as short as a few years, but instead occurred gradually over about ten million years, a time frame more consistent with longer term events such as massive volcanism. Several scientists think the extensive volcanic activity in India known as the Deccan Traps may have been responsible for, or contributed to, the extinction. A partial reason for the rejection of the impact theory may have been a certain general distrust of a group of physicists intruding into the paleontologists' domain of expertise.

Luis Alvarez, who died in 1988, replied that paleontologists were being misled by sparse data. His assertion did not go over well at first, but later intensive field studies of fossil beds lent weight to his claim. Eventually, most paleontologists began to accept the idea that the mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous were largely or at least partly due to a massive Earth impact. However, even Walter Alvarez has acknowledged that there were other major changes on Earth even before the impact, such as a drop in sea level and massive volcanic eruptions in India (Deccan Traps sequence), and these may have contributed to the extinctions.

A very large impact crater has been recently reported in the sea floor off the west coast of India 2. This, the Shiva crater (450/600 km diam.), has also been dated at about 65 million years at the K-T boundary. The researchers suggest that the impact may have been the triggering event for the Deccan Traps. However, this feature has not yet been accepted by the geologic community as an impact crater and may just be a sinkhole depression caused by salt withdrawal. [2].

Multiple impact event

Several other craters also appear to have been formed at the K-T boundary. This suggests the possibility of near simultaneous multiple impacts from perhaps a fragmented asteroidal object, similar to the Shoemaker-Levy 9 cometary impact with Jupiter.

- Boltysh crater (24 km diam., 65.17 ± 0.64 Ma old) in Ukraine

- Silverpit crater (20 km diam., 60-65 Ma old) in the North Sea

- Eagle Butte crater (10 km diam., < 65 Ma old) in Alberta, Canada

- Vista Alegre crater (9.5 km diam., < 65 Ma old) in Paraná State, Brazil

Note: Ma means million years.

Supernova hypothesis

Another proposed cause for the K-T extinction event was cosmic radiation from a relatively nearby supernova explosion. The iridium anomaly at the boundary could support this hypothesis. The fallout from a supernova explosion should contain the plutonium isotope Pu-244, the longest-lived plutonium isotope (half-life 81 Myr), that is not found in earth rocks. However, analysis of the boundary layer sediments revealed the absence of Pu-244, thus essentially disproving this hypothesis.

Further skepticism

Skeptics remain. Although there is now general agreement that there was at least one huge impact at the end of the Cretaceous that led to the iridium enrichment of the K-T boundary layer, it is difficult to directly connect this to mass extinction, and in fact there is no clear linkage between an impact and any other incident of mass extinction, although research on other events also implicates impacts.

One interesting note about the K-T event is that most of the larger animals that survived were to some degree aquatic, implying that aquatic habitats may have remained more hospitable than land habitats.

The impact and volcanic theories can be labeled "fast extinction" theories. There are also a number of slow extinction theories. Studies of the diversity and population of species have shown that the dinosaurs were in decline for a period of about 10 million years before the asteroid hit. (A study by Fastovsky & Sheehan (1995) counters that there is no evidence for a slow, 10 Myr decline of dinosaurs.) Slower mechanisms are needed to explain slow extinctions. Climatic change, a change in Earth's magnetic field, and disease have all been suggested as possible slow extinction theories. As mentioned above, extensive volcanism such as the Deccan Traps could have been a long term event lasting millions of years, although it is short in geologic terms.

References: Favstovsky, D.E., and Sheehan, P.M.(2005) The extinction of the dinosaurs in North America. GSA Today, v. 15, no. 3, p. 4-10.

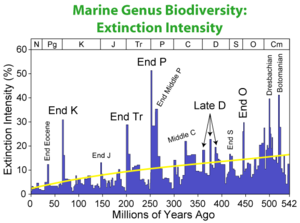

Other mass extinctions

It is worth noting that the Cretaceous extinction is neither the only mass extinction in Earth's history, nor even the worst. Previous extinction events have included the Cambrian-Ordovician extinction, End Ordovician, Triassic-Jurassic, Late Devonian, and the Permian-Triassic, which is the largest extinction event ever recorded.

References and external links

- Understanding the K-T Boundary - NASA-related website

- Shiva crater: Chatterjee et al. 2002 Volcanism, India-Seychelles Rifting, Dinosaur Extinction, and Petroleum Entrapment at the KT Boundary (GSA abstract)

- List of 172+ impact craters in Earth Impact Database with Crater name, Diameter, Age, Country, Latitude, Longitude, etc.

- Air bubbles, amber, and dinosaurs

- Earth Impact Database

- "The KT Boundary" - BBC Radio 4 Broadcast, In Our Time, 23rd June 2005 - hosted by Melvyn Bragg (duration: approximately 45 minutes)