Late Bronze Age collapse

| Bronze Age |

|---|

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

| ↓ Iron Age |

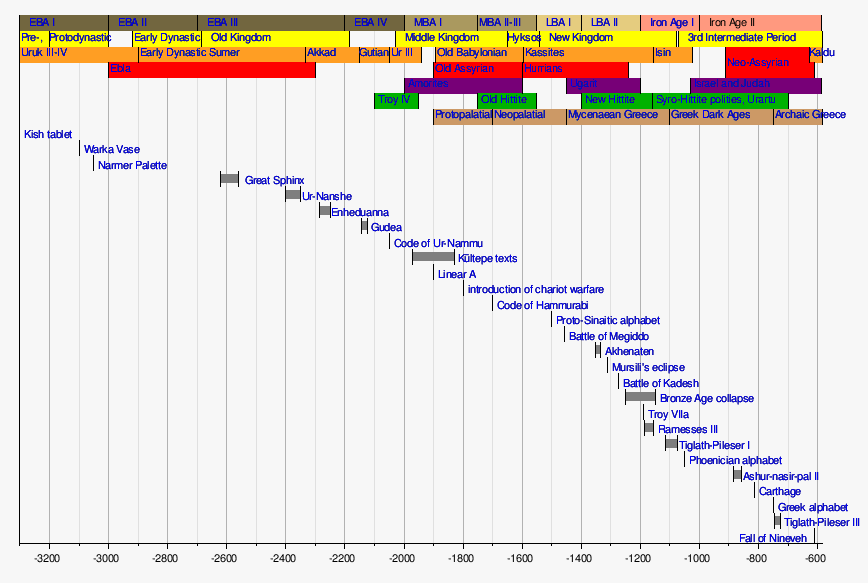

Template:FixBunching Template:Ancient Near East portal Template:FixBunching The Bronze Age collapse is the name given by those historians who see the transition in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, as violent, sudden and culturally disruptive. The palace economies of the Aegean and Anatolia which characterised the Late Bronze Age were replaced, after a hiatus, by the isolated village cultures of the Ancient Dark Age.

Between 1206 and 1150 BC, the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria,[1] and the Egyptian Empire in Syria and Canaan,[2] interrupted trade routes and extinguished literacy. In the first phase of this period, almost every city between Troy and Gaza was violently destroyed, and often left unoccupied thereafter: examples include Hattusa, Mycenae, Ugarit.

The gradual end of the Dark Age that ensued saw the rise of settled Neo-Hittite Aramaean kingdoms of the mid-10th century BC, and the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Regional evidence

Anatolia

Every important site during the preceding Late Bronze Age shows a destruction layer, and it appears that here civilization did not recover to the same level as that of the Hittites for another thousand years. Hattusas, the Hittite capital, was burned and abandoned, and never reoccupied. Karaoglan was burned and the corpses left unburied. Troy was destroyed at least twice, before being abandoned until Roman times.

Cyprus

The catastrophe separates Late Cypriot II (LCII) from the LCIII period, with the sacking and burning of the sites of Enkomi, Kition, and Sinda, may have occurred twice, before being abandoned. A number of sites, though not destroyed, were also abandoned. Kokkinokremos was a short-lived settlement, where the presence of various caches concealed by smiths suggests that none ever returned to reclaim the treasures, suggesting they were killed or enslaved.

Syria

Syrian sites previously showed evidence of trade links with Egypt and the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age. Evidence at Ugarit shows that the destruction there occurred after the reign of Merenptah, and even the fall of Chancellor Bay. Letters on clay tablets found baked in the conflagration of the destruction of the city speak of attack from the sea, and a letter from Alashiya (Cyprus) speaks of cities already being destroyed from attackers who came by sea. It also speaks of the Ugarit fleet being absent, patrolling the coast.

Levant

Egyptian evidence shows that from the reign of Horemheb, wandering Shasu were more problematic. Ramesses II campaigned against them, pursuing them as far as Moab, where he established a fortress, after the near collapse at the Battle of Kadesh. These Shasu were problematic, particularly when during the reign of Merneptah, they threatened the "Way of Horus" north from Gaza. Evidence shows that Deir Alla (Succoth) was destroyed after the reign of Queen Twosret. The destroyed site of Lachish was briefly reoccupied by squatters and an Egyptian garrison, during the reign of Ramesses III. All centres along a coastal route from Gaza northward were destroyed, and evidence shows Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Akko, and Jaffa were burned and not reoccupied for up to thirty years. Inland Hazor, Bethel, Beit Shemesh, Eglon, Debir, and other sites were destroyed. Refugees escaping the collapse of coastal centres may have fused with incoming nomadic and Anatolian elements to begin the growth of terraced hillside hamlets in the highlands region, that was associated with the later development of the Hebrews.

Greece

None of the Mycenaean palaces of the Late Bronze Age survived, with destruction being heaviest at palaces and fortified sites. Up to 90% of small sites in the Peloponnese were abandoned, suggesting a major depopulation. The End Bronze Age collapse marked the start of what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, which lasted for more than 400 years. Other cities, like Athens, continued to be occupied, but with a more local sphere of influence, limited evidence of trade and an impoverished culture, from which it took centuries to recover.

Mesopotamia

The cities of Norsuntepe, Emar and Carchemish were destroyed, Assyria loses north western cities to Mushki, which are reconquered first by Tiglath-Pileser I after his ascension to kingship. With the spread of Ahhlamu, or Aramaeans, control of the Babylonian and Assyrian regions extended barely beyond the city limits. Babylon was sacked by the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte, and lost control of the Diyala valley.

Egypt

After apparently surviving for a while, the Egyptian Empire collapsed in the mid twelfth century BC (during the reign of Ramesses VI). Previously the Merneptah Stele spoke of attacks from Libyans, with associated people of Ekwesh, Shekelesh, Lukka, Shardana and Tursha or Teresh, and a Canaanite revolt, in the cities of Ashkelon, Yenoam and the people of Israel. A second attack during the reign of Ramesses III involved Peleset, Tjeker, Shardana and Denyen.

Conclusion

Robert Drews describes the collapse as "the worst disaster in ancient history, even more calamitous than the collapse of the Western Roman Empire".[3] A number of people have spoken of the cultural memories of the disaster as stories of a "lost golden age". Hesiod for example spoke of Ages of Gold, Silver and Bronze, separated from the modern harsh cruel world of the Age of Iron by the Age of Heroes.

Possible causes of collapse

As part of the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age Dark Ages, it was a period associated with the collapse of central authorities, a general depopulation, particularly of highly urban areas, the loss of literacy in Anatolia and the Aegean, and its restriction elsewhere, the disappearance of established patterns of long-distance international trade, increasingly vicious intra-elite struggles for power, and reduced options for the elite if not for the general mass of population.

There are various theories put forward to explain the situation of collapse, many of them compatible with each other.

Volcanos

The Hekla 3 eruption approximately coincides with this period and, while the exact date is under considerable dispute, has been specifically dated to 1159 BC by Egyptologists[4] and British archeologists[5].

Earthquakes

Amos Nur shows how earthquakes tend to occur in "sequences" or "storms" where a major earthquake above 6.5 on the Richter magnitude scale can in later months or years set off second or subsequent earthquakes along the weakened fault line. He shows that when a map of earthquake occurrence is superimposed on a map of the sites destroyed in the Late Bronze Age, there is a very close correspondence.[6]

Migrations and raids

Ekrem Akurgal, Gustav Lehmann and Fritz Schachermeyer, following the views of Gaston Maspero have argued on the basis of the wide spread findings of Naue II-type swords coming from South Eastern Europe, and Egyptian records of "northerners from all the lands".[7]

The Ugarit correspondence draws attention to such groups as the mysterious Sea Peoples. Equally, translation of the preserved Linear B documents in the Aegean, just before the collapse, demonstrates a rise in piracy and slave raiding, particularly coming from Anatolia. Egyptian fortresses along the Libyan coast, constructed and maintained after the reign of Ramesses II were constructed to reduce raiding.

Ironworking

Leonard R. Palmer suggested that iron, whilst inferior to bronze weapons, was in more plentiful supply and so allowed larger armies of iron users to overwhelm the smaller armies of bronze-using maryannu chariotry.[8] This argument has been weakened of late with the finding that the shift to iron occurred after the collapse, not before.[citation needed] It now seems that the disruption of long distance trade, an aspect of "systems collapse", cut easy supplies of tin, making bronze impossible to make. Older implements were recycled and then iron substitutes were used.

Drought

Harvey Weiss, professor of Near Eastern archeology at Yale,[9] using the Palmer Drought Index for 35 Greek, Turkish, and Middle Eastern weather stations, showed that a drought of the kinds that persisted from January 1972 would have affected all of the sites associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[10] Drought could have easily precipitated or hastened socio-economic problems and led to wars. More recently Brian Fagan has shown how the diversion of mid-winter storms, from the Atlantic to north of the Pyrenees and the Alps, bringing wetter conditions to Central Europe but drought to the Eastern Mediterranean, was associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse.[11]

General systems collapse

A general systems collapse has been put forward as an explanation for the reversals in culture that occurred between the Urnfield culture of the 12-13th centuries BC and the rise of the Celtic Hallstatt culture in the 9th and 10th centuries.[12] This theory may, however, simply raise the question of whether this collapse was the cause of, or the effect of, the Bronze Age collapse being discussed. General Systems Collapse theory, pioneered by Joseph Tainter,[13] hypothesizes how social declines in response to complexity may lead to a collapse resulting in simpler forms of society.

In the specific context of the Middle East, a variety of factors - including population rise, soil degradation, drought, cast bronze weapon and iron production technologies - could have combined to push the relative price of weaponry (compared to arable land) to a level unsustainable for traditional warrior aristocracies.

Changes in warfare

Robert Drews argues[14] that the appearance of massed infantry, using newly developed weapons and armor, such as cast rather than forged spearheads and long swords, a revolutionizing cut-and-thrust weapon,[15] and javelins, and the appearance of bronze foundries, suggest "that mass production of bronze artifacts was suddenly important in the Aegean". (For example, Homer uses "spears" as a virtual synonym for "warrior", suggesting the continued importance of the spear in combat.) Such new weaponry, furnished to a proto-hoplite model of infantry which was able to withstand attacks of massed chariotry, would destabilize states that were based upon the use of chariots by the ruling class and precipitate an abrupt social collapse as raiders and/or infantry mercenaries began to conquer, loot, and burn the cities.[16][1][2]

References

- ^ For Syria, see M. Liverani, "The collapse of the Near Eastern regional system at the end of the Bronze Age: the case of Syria" in Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, M. Rowlands, M.T. Larsen, K. Kristiansen, eds. (Cambridge University Press) 1987.

- ^ S. Richard, "Archaeological sources for the history of Palestine: The Early Bronze Age: The rise and collapse of urbanism", The Biblical Archaeologist (1987)

- ^ Drews, The End of the Bronze Age:changes in warfare and the catastrophe c. 1200 B.C., 1993:1, quotes Fernand Braudel's assessment that the Eastern Mediterranean cultures returned almost to a starting-point ("plan zéro"), "L'Aube", in Braudel, F. (Ed) (1977), La Mediterranee: l'espace et l'histoire (Paris)

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1999). "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause". in Teeter, Emily; Larson, John (eds.). Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. 58. Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute of the Univ. of Chicago. pp. 456–458. ISBN 1885923090.

- ^ a b c Cunliffe, Barry (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain (4th ed.). Routledge. pp. 256. ISBN 0415347793. Pg 68

- ^ Nur, Amos and Cline, Eric; (2000) "Poseidon's Horses: Plate Tectonics and Earthquake Storms in the Late Bronze Age Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean", Journ. of Archael. Sc. No 27 pps.43-63 - http://srb.stanford.edu/nur/EndBronzeage.pdf

- ^ Robbins, Manuel (2001) Collapse of the Bronze Age: the story of Greece, Troy, Israel, Egypt and Peoples of the Sea" (Authors Choice Press)

- ^ Palmer, Leonard R (1962) Mycenaeans and Minoans: Aegean Prehistory in the Light of the Linear B Tablets. (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1962)

- ^ Weiss, Harvey: (1982) "The decline of Late Bronze Age civilization as a possible response to climatic change" in Climatic Change ISSN 0165-0009 (Paper) 1573-1480 (Online), Volume 4, Number 2, June 1982, pps 173 - 198

- ^ Wright, Karen: (1998) "Empires in the Dust" in "Discover Magazine" March 1998 issue. http://discovermagazine.com/1998/mar/empiresinthedust1420

- ^ Fagan, Brian M. (2003), "The Long Summer: How Climate Changed Civilization (Basic Books)

- ^ http://www.iol.ie/~edmo/linktoprehistory.html - a page about the history of Castlemagner, on the web page of the local historical society.

- ^ Tainter, Joseph: (1976) "The Collapse of Complex Societies" (Cambridge University Press)

- ^ Drews pp192ff.

- ^ The Naue Type II sword, introduced from the eastern Alps and Carpathians ca 1200, quickly established itself and became the only sword in use during the eleventh century; iron was substituted for bronze without essential redesign (Drews 1993:194.

- ^ Drews, R. (1993) The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. (Princeton 1993).

- Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC Routledge (2007), ISBN 978-0415135900.