Battle of Iron Works Hill

| Battle of Iron Works Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

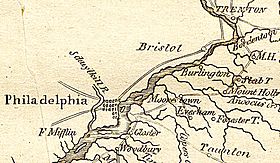

An 1806 map showing Philadelphia, PA, Trenton, and Mount Holly, NJ. "Blackhorse" is roughly at the place labelled "M.H." | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500–600 militia[1] | 2,000 British and Hessian troops[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| minor (see Aftermath)[3] | minor (see Aftermath)[3] | ||||||

Template:FixBunching The Battle of Iron Works Hill, also known as the Battle of Mount Holly, was a series of minor skirmishes that took place on December 22 and 23, 1776 during the American War of Independence. They took place in Mount Holly, New Jersey, between an American force mostly composed of colonial militia under Colonel Samuel Griffin and a force of 2,000 Hessian mercenaries and British Army regulars under Carl von Donop.

While the American force of 600 was eventually forced from their positions by the larger British force, the action prevented Donop from being in his assigned base at Bordentown, New Jersey and in a position to assist Johan Rall's brigade in Trenton, New Jersey when it was attacked and defeated by George Washington after his troops crossed the Delaware on Christmas night.[4][5]

Background

In July 1776 forces of Great Britain under the command of General William Howe landed on Staten Island. Over the next several months, Howe's forces, which were British Army regulars and hired German troops usually referred to as Hessian, chased George Washington's Continental Army out of New York City and across New Jersey.[6] Washington's army, which was shrinking in size due to expiring enlistments, and desertions due to poor morale, took refuge in Pennsylvania on the western shore of the Delaware River in November, removing all the available watercraft to deny the British any opportunity to cross the wide river.[7]

General Howe established a chain of outposts across New Jersey, and ordered his troops into winter quarters. The southernmost outposts were located at Trenton and Bordentown.[8] The Trenton outpost was manned by about 1,500 German troops from Hesse-Kassel under the command of Johann Rall, and the Bordentown outpost was manned by Hessians and the British 42nd Regiment, about 2,000 troops in all, under the command of the German Carl von Donop.[2] Bordentown itself was not large enough to house all of Donop's brigade. While he had hoped to quarter some troops even further south at Burlington, where there was strong Loyalist support, floating gun batteries from the Pennsylvania Navy threatened the town, and Donop, rather than expose Loyalist allies to their fire, was forced to scatter his troops throughout the surrounding countryside.[9]

As the troops of Donop and Rall occupied the last outposts, they were often exposed to the actions of Continental Army raids and the actions of Patriot militia forces that either arose spontaneously or were recruited by Army regulars. These actions frayed the nerves of the troops, as the uncertainty of when and where such attacks would take place, and by what size force, put the men and their commanders on edge, leading them to jump up to investigate every rumored movement. Rall went so far as to order his men to sleep "fully dressed like [they were] on watch."[10]

One militia force that arose in December 1776 was a company under the command of Virginia Colonel Samuel Griffin. Griffin (whose name is sometimes misspelled "Griffith") was the adjutant to General Israel Putnam, who was responsible for the defense of Philadelphia. His force, whose exact composition is uncertain, probably included some Virginia artillerymen, Pennsylvania infantry, and New Jersey militia, and numbered five to six hundred.[1] By mid-December he had reached Moorestown, south of Mount Holly, and rumors of his presence reached Donop.[11] Donop sent a Loyalist to investigate, who reported a force of "not above eight hundred, nearly one half boys, and all of them Militia a very few from Pennsylvania excepted".[12] Thomas Stirling, the commander of the 42nd, heard rumors that there were 1,000 rebels at Mount Holly, and that "2,000 more were in the rear to support them", and began pulling in his foraging parties.[12] When Donop asked Stirling for advice, he replied that "You sir, with the troops at Bordentown, should come here and attack. I am confident we are a match for them."[13] Griffin had advanced to Mount Holly and established a rough fortification atop a hill near an iron works, south of Rancocas Creek and the village center.[14]

Battle

On December 22, Donop rode down to Blackhorse (present-day Columbus), where the 42nd was quartered, to investigate the situation. After learning that Griffin's men were at Mount Holly, he returned to Bordentown, only to hear alarm shots from Blackhorse. According to Donop's journal (a document that historian David Hackett Fischer believes is of dubious reliability)[15] a guard outpost of the 42nd was attacked at Petticoat bridge by Griffin's full force, and made to retreat before being reinforced by nearby British and Hessian troops.[16]

On the evening of December 22, Washington's adjutant, Joseph Reed, went to Mount Holly and met with Griffin. Griffin had written to Reed, requesting small field pieces to assist in their actions, and Reed, who had been discussing a planned attack on Rall's men in Trenton with Washington, wanted to see if Griffin's company could participate in some sort of diversionary attack. Griffin was ill, and his men ill-equipped for significant action, but they apparently agreed to some sort of actions the next day.[17]

The next day, Donop brought his full brigade (the 42nd and the Hessian regiments Block and Linsing) to Mount Holly, where he reported scattering about 1,000 men near the town's meeting house. Jäger Captain Johann Ewald reported that "some 100 men" were posted on a hill "near the church", who "retired quickly" after a few rounds of artillery were fired.[18] Griffin, whose men had occupied Mount Holly, slowly retreated to their fortified position on the hill, following which the two sides engaged in ineffectual long-range gunfire.[19]

Aftermath

Donop's forces bivouacked in Mount Holly on the night of December 23, where, according to Ewald, they plundered the town, breaking into alcohol stores of abandoned houses and getting drunk.[13] Donop himself took quarters in the house that Ewald described as belonging to an "exceedingly beautiful widow of a doctor",[13] whose identity is presently uncertain.[20][21] The next day (Christmas Eve), they moved in force to drive the militia from the hill, but Griffin and his men had retreated during the night.[19] For whatever reason, Donop and his full brigade again remained in Mount Holly, 18 miles (29 km) and a full day's march from Trenton,[20] until a messenger arrived on December 26, bringing the news of Rall's defeat by Washington that morning.[19]

News of the skirmishes at Mount Holly was often exaggerated. Published accounts of the day varied, including among participants in the battle. One Pennsylvanian claimed that sixteen of the enemy were killed, while a New Jersey militiaman reported seven enemy killed.[3] Both Donop and Ewald specifically denied any British or German casualties occurred during the first skirmish on December 22,[21], while the Pennsylvania Evening Post reported "several" enemy casualties with "two killed and seven or eight wounded" of the militia through the whole action.[3]

Some reporters, including Loyalist Joseph Galloway, assumed that Griffin had been specifically sent to draw Donop away from Bordentown, but Donop's decision to attack in force was apparently made prior to Reed's arrival. Reed noted in his journal that "this manouver [sic], though perfectly accidental, had a happy effect as it drew off Count Donop ..."[3] The planning for Washington's crossing of the Delaware did include sending a militia force to Griffin in an attack on Donop at Mount Holly; this company failed to cross the river.[22]

Legacy

The hill that Griffin's militia occupied is located at Iron Works Park in Mount Holly. The battle is reenacted annually.[23]

Notes

- ^ a b Fischer, p. 198. Dwyer, p. 211

- ^ a b Dwyer, p. 151

- ^ a b c d e Dwyer, p. 216

- ^ Rosenfeld p. 177

- ^ Di Ionno p. 29

- ^ Dwyer, p. 5

- ^ The retreat is recounted in detail by Dwyer, pp. 24-112.

- ^ Fischer, p. 185

- ^ Dwyer, pp. 170-173

- ^ Fischer, p. 196

- ^ Dwyer, p. 213

- ^ a b Fischer, p. 198

- ^ a b c Fischer, p. 199

- ^ Rizzo, p. 80

- ^ Fischer, p. 423

- ^ Dwyer, p. 214

- ^ Reed, p. 273

- ^ Dwyer, pp. 214-215

- ^ a b c Rizzo, p. 82

- ^ a b Fischer, p. 200

- ^ a b Dwyer, p. 215

- ^ Dwyer, p. 241

- ^ Battle of Iron Works Hill reenactment

References

- Di Ionno, Mark (2000). A Guide to New Jersey's Revolutionary War Trail: For Families and History Buffs. ISBN 0813527708.

- New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past. US History Publishers. ISBN 1603540296.

- Dwyer, William M (1983). The Day is Ours!. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670114464.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019518159X.

- Reed, William Bradford (1847). Life and correspondence of Joseph Reed, Volume 1. Lindsay & Blakiston.

- Rizzo, Dennis (2007). Mount Holly, New Jersey: A Hometown Reinvented. The History Press. ISBN 9781596292765.

- "Battle of Iron Works Hill reenactment". Main Street Mount Holly. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

Further reading

- Rosenfeld, Lucy D (2006). History Walks in New Jersey: Exploring the Heritage of the Garden State. ISBN 0813539692.