Ahmad Shah Massoud

Ahmad Shah Massoud | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Lion of Panjshir" |

| Allegiance | United Front (Northern Alliance) |

| Rank | Commander, Minister of Defense |

| Commands | Prominent Mujahideen commander during the Soviet war in Afghanistan, Defense Minister of Afghanistan, leading commander of the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan |

| Awards | National Hero of Afghanistan and Nobel Peace Prize Nominee |

Ahmad Shah Massoud (احمد شاه مسعود- Aḥmad Šāh Mas‘ūd; September 1953 – September 9, 2001) was a Kabul University engineering student turned military leader who played a leading role in driving the Soviet army out of Afghanistan, earning him the nickname Lion of Panjshir. His followers call him Āmir Sāhib-e Shahīd (Our Martyred Commander). An ethnic Tajik, Massoud was a moderate of the anti-Soviet resistance leaders.[1]

Following the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet-backed government of Mohammad Najibullah, Massoud became the Defense Minister in 1992 under the government of former Afghan President Burhanuddin Rabbani. Following the collapse of Rabbani's government and the rise of the Taliban in 1996, Massoud returned to the role of an armed opposition leader, serving as the military commander of the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan (known in the Western and Pakistani media as the Northern Alliance).

On September 9, 2001, two days before the September 11 attacks in the United States, Massoud was assassinated in Takhar Province of Afghanistan by suspected al-Qaeda agents. The following year, he was named "National Hero" by the order of Afghan President Hamid Karzai. The date of his death, September 9, is observed as a national holiday in Afghanistan, known as "Massoud Day."[2] The year following his assassination, in 2002, Massoud was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.[3]

Early life

The son of police commander Dost Mohammad, Ahmad Shah Massoud was born on September 2, 1953 in Bazarak, Panjshir, Afghanistan. At the age of five, he started grammar school in Bazarak and stayed there until second grade. Since his father was promoted to be police chief of Herat, he attended 3rd and 4th grade at the Mowaffaq School in Herat. He also received a religious education at the "Masjed-e Jame" mosque in Herat. Later, his father was moved to Kabul where he attended the Lycée Esteqlal and obtained his Baccalaureate. Since his childhood, he was considered exceedingly talented; from 10th grade on, his school acknowledged him as a particularly gifted student. He knew many languages including Persian, Pashto, Urdu and Hindi, and he also spoke French in his early years as a commander.[4] He also had a good working knowledge of Arabic and English.[5]

While studying in Kabul in 1972, Massoud became involved with the Sazman-i Jawanan-i Musulman ("organization of Muslim youth"), the student branch of the Jamiat Islami ("Islamic Society"), whose chairman was professor Burhanuddin Rabbani. This Islamist organization opposed the rising communist influence that became especially evident after the coup d'état that brought Mohammed Daoud Khan to power in 1973: the coup was orchestrated by the Parcham faction of the PDPA, the Afghan communist party. In July 1975, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, then a Jamiat member, organized an uprising against Daoud's government. Massoud was placed in charge of the Panjshir resistance and had some success in this area, but the revolt ultimately failed due to lack of support among the people and Gulbuddin's inability to entice officers of the Afghan army to join the resistance.[6] The ensuing repression greatly weakened the Islamist movement and forced the surviving militants back to Pakistan.

In 1976, the movement split between supporters of Rabbani, who led the Jamiat, and the more fundamentalists members of Hekmatyar, who founded the Hezbi Islami. Massoud, who blamed the failure of the insurrection on Hekmatyar, joined Rabbani's faction.[citation needed]

1978 Revolution in Afghanistan

In 1978, the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (حزب دیموکراتیک خلق افغانستان) came to power, and they began to reform Afghanistan along Marxist lines. These reforms were met with resistance, especially as the government attempted to enforce its Marxist policies by arresting or simply executing those who resisted. The repression plunged large parts of the country, especially the rural areas, into open revolt against the new Marxist government. Islamist intellectuals such as Massoud became leaders of these uprisings.

The first instance of open rebellion occurred in Nuristan, in July 1978. Massoud joined the rebels, and was present when they wiped out an armoured battalion sent by the PDPA to suppress the revolt.[7]

Having ascertained that an uprising against the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan would be backed by the people, Massoud made his way to the Panjshir and started a new insurrection on July 6, 1979. The fight lasted 40 days, during which the whole Panjshir, Salang, and Bola Ghain were in open revolt against the Marxist government. After these 40 days, Massoud's leg was injured and the troops under his command had no more weapons and ammunition. Despite 600 relief fighters from Nuristan, the government troops finally defeated them.[8] Drawing lessons from this failure, Massoud decided to avoid direct confrontation with government troops and to wage a guerrilla war. He set about creating bases and giving his men training in guerilla warfare tactics.[9]

Soviet invasion and occupation

Following the 1979 invasion and occupation of Afghanistan by Soviet troops, Massoud devised a strategic plan for expelling the invaders and overthrowing the communist regime. The first task was to establish a guerilla force, supported by the people. The second phase was one of "active defense" of the Panjshir stronghold, while carrying out irregular warfare. The third phase, the "strategic offensive", would see Massoud's forces taking control of large parts of Northern Afghanistan. The fourth phase was the "general application" of Massoud's principles to the whole country, and the final demise of the Afghan communist government.

Massoud's resistance efforts ultimately drew military and other support from the United States during the administrations of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. Under the Reagan administration, U.S. support for the mujahideen ultimately evolved into an official U.S. foreign policy doctrine, known as the Reagan Doctrine, under which the U.S. supported anti-Soviet resistance movements in Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua and elsewhere.[10] U.S. support for Massoud and his forces grew considerably in the late 1980s.

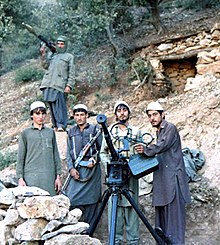

From the start of the war, Massoud's mujahideen proved to be a thorn in the side for the occupying Soviet forces by ambushing Soviet and Afghan convoys travelling through the Salang Pass, resulting in fuel shortages in Kabul.[11] To relieve the pressure on their supply lines, the Soviets were forced to mount a series of offensives against the Panjshir. Between 1980 and 1985, these offensives were conducted twice a year. Yet, despite engaging more men and hardware on each occasion, the Soviets were unable to defeat Massoud's forces. In 1982, the Soviets began deploying major combat units in the Panjshir numbering up to 12,000 men, and Massoud pulled his troops back into subsidiary valleys, where they occupied fortified positions. When the Soviet columns advanced onto these positions, they fell into ambushes and suffered heavy casualties. When the Soviets withdrew, they handed over their positions to Afghan army garrisons, and Masoud and his mujahideen forces attacked and recaptured them one by one.[12]

In 1983, the Soviets offered Massoud a truce, which he accepted. He put this respite to good use, extending his influence to areas outside Panjshir, mostly in Takhar and Baghlan Provinces.

This expansion prompted Babrak Karmal to demand that the Red Army resume their offensives, in order to crush the Panjshir groups definitively. However, Massoud had received advance warning of the attack through his agents in the government and he evacuated all 30,000 inhabitants from the valley, leaving the Soviet bombings to fall on empty ground.[13] Eventually, after 1985, no more offensives were carried out against the Panjshir.

With the end of the Soviet-Afghan attacks, Massoud was able to carry out the next phase of his strategic plan, expanding the resistance movement and liberating the northern provinces of Afghanistan. In August 1986, he captured Farkhar in Takhar Province. In November 1986, his forces overran the headquarters of the government's 20th division at Nahrin in Baghlan Province, scoring an important victory for the resistance.[14] This expansion was also carried out through diplomatic means, as more mujahideen commanders were persuaded to adopt the Panjshir military system.

Despite almost constant attacks by the Red army and the Afghan army, Massoud was able to increase his military strength. Starting in 1980 with a force of less than 1,000 ill-equipped guerillas, the Panjshir valley mujahideen grew to a 5,000-strong force by 1984.[11] After expanding his influence outside the valley, Massoud increased his resistance forces to 13,000 fighters by 1989.[15] These forces were divided into different types of units: the locals (mahalli) were tasked with static defense of villages and fortified positions. The best of the mahalli were formed into units called grup-i zarbati (shock troops), semi-mobile groups that acted as reserve forces for the defense of several strongholds. A different type of unit was the mobile group (grup-i-mutaharek), a lightly equipped commando-like formation numbering 33 men, whose mission was to carry out hit-and-run attacks outside the Panjshir, sometimes as far as 100 km from their base. These men were professional soldiers, well-paid and trained, and, from 1983 on, they provided an effective strike force against government outposts. Uniquely among the mujahideen, these groups wore uniforms, and their use of the pakul made this headwear emblematic of the Afghan resistance.

Massoud's military organization was an effective compromise between the traditional Afghan method of warfare and the modern principles of guerilla warfare that Massoud had learned from the works of Mao Zedong and Che Guevara. His forces were considered the most effective of all the various Afghan resistance movements.[16]

In July 1983, Massoud created the Shura-ye-nazar (council of supervision), a military council that would eventually coordinate the actions of 130 mujahideen commanders from seven provinces of northern Afghanistan: Parwan, Laghman, Kapisa, Kunar, Badakshan, Takhar, Baghlan and Kunduz . This council existed outside the fold of the Peshawar parties that were prone to internecine rivalry and bickering, and served to smooth out differences between resistance groups, due to political and ethnic divisions. It was the predecessor of what would ultimately become the "Northern Alliance."[17]

Relations with the party headquarters in Peshawar were often strained, as Rabbani insisted on giving Massoud no more weapons and supplies than to other Jamiat commanders, even those who did little fighting. To compensate for this deficiency, Massoud relied on revenues drawn from exports of emeralds[18] and lapis lazuli,[19] that are traditionally exploited in Northern Afghanistan.

To organize support for the mujahideen, he established an administrative system that enforced law and order (nazm) in areas under his control. The Panjshir was divided into 22 bases (qarargah) governed by a military commander and a civilian administrator, and each had a judge, a prosecutor and a public defender.[20]

Massoud's policies were implemented by different committees: an economic committee was charged with funding the war effort. The health committee provided health services, assisted by volunteers from foreign humanitarian non-governmental organizations, such as Aide médicale internationale. An education committee was charged with the training of the military and administrative cadre. A culture and propaganda committee and a judiciary committee were also created.[21]

United States and Pakistan's role in Afghanistan

The U.S. through Pakistan gave only little support to Massoud. The U.S. let Pakistan handle the daily administration of funding and arms distribution. Pakistan favored the criminal Gulbuddin Hekmatyar

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

, who was under their control and is nowadays attacking ISAF-troops and the civilian population in Afghanistan, over the more talented and independent Massoud

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

. In an interview Massoud expressed: "We though the CIA knew everything. But they didn't. They supported some bad people [meaning Hekmatyar]." Primary advocates for supporting Massoud instead were State Department's Edmund McWilliams and Peter Tomsen, who were on the ground in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Others included two Heritage Foundation foreign policy analysts, Michael Johns and James A. Phillips, both of whom championed Massoud as the Afghan resistance leader most worthy of U.S. support under the Reagan Doctrine.[22][23] Still, the Soviet army and the Afghan communist army were defeated by primarily Massoud

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

and the mujahideen in numerous small engagements between 1984 and 1988, but many of these battles remain either undocumented or unknown to outside sources.

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

However, the strength of the Afghan resistance continued to grow in the late 1980s, fueled by increased U.S. support and associated military success of the Afghan resistance forces, causing the Soviet Union to rethink its occupation of the country. In 1989, after labeling the Soviet Union's military engagement in Afghanistan "a bleeding wound", Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev began a withdrawal of Soviet troops from the nation. On February 15, 1989, in what was depicted as an improbable victory for the mujahideen, the last Soviet soldier left the nation.

Fall of Kabul in 1992

After the departure of Soviet troops in 1989, the PDPA regime, then headed by Mohammad Najibullah, proved unexpectedly capable holding of its own against the mujahideen. Backed by a massive influx of weapons from the Soviet Union, the Afghan armed forces reached a level of performance they had never reached under direct Soviet tutelage and were able to maintain control over all of Afghanistan's major cities.

By 1992, however, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the regime began to crumble. Food and fuel shortages undermined the capacities of the government's army, and a resurgence of factionalism split the regime between Khalq and Parcham supporters.[24]

A few days after it was clear that Najibullah had lost control of the nation, his army commanders and governors arranged to turn over authority to resistance commanders and local notables throughout the country. Joint councils (shuras) were immediately established for local government in which civil and military officials of the former government were usually included. In many cases, prior arrangements for transferring regional and local authority had been made between foes.[24]

Collusions between military leaders quickly brought down the Kabul government. In mid-January 1992, within three weeks of the demise of the Soviet Union, Massoud was aware of conflict within the government's northern command. General Abdul Momim, in charge of the Hairatan border crossing at the northern end of Kabul's supply highway, and other non-Pashtun generals based in Mazari Sharif feared removal by Najibullah and replacement by Pashtun officers. The generals rebelled and the situation was taken over by Abdul Rashid Dostum, who held general rank as head of the Jowzjani militia, also based in Mazari Sharif. He and Massoud reached a political agreement, together with another major militia leader, Sayyed Mansour, of the Ismaili community based in Baghlan Province. These northern allies consolidated their position in Mazar-i-Sharif on March 21. Their coalition covered nine provinces in the north and northeast. As turmoil developed within the government in Kabul, there was no government force standing between the northern allies and the major air force base at Bagram, some seventy kilometers north of Kabul. By mid-April 1992, the Afghan air force command at Bagram had capitulated to Massoud. Kabul was defenseless and its army no longer reliable.[24]

On March 18, 1992, Najibullah announced his willingness to resign, and on April 17, as his government fell apart, he tried to escape but was stopped at Kabul Airport by Dostum's forces. He then took refuge at the United Nations mission, where he remained until 1995. A group of Parchami generals and officials declared themselves an interim government for the purpose of handing over power to the mujahideen.[24]

For more than a week, Massoud remained poised to move his forces into the capital. He was awaiting the arrival of political leadership from Peshawar. The parties suddenly had sovereign power in their grasp, but no plan for executing it. With his principal commander prepared to occupy Kabul, Rabbani was positioned to prevail by default. Meanwhile UN mediators tried to find a political solution that would assure a transfer of power acceptable to all sides.[24]

The civil war and the role of foreign powers

War in Kabul and other parts of the country incited by Hekmatyar and Pakistan (1992-1996)

When political leaders finally signed a peace agreement called the Peshawar Accords, Massoud was given the position of defense minister. Burnahuddin Rabbani became president. Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, however, wanted all power for himself dooming the peace agreement to fail. [verification needed] With the strong support of Pakistan, he placed Kabul under intensive rocket bombardment in February 1993. Some sources cite up to 3,000 rockets being fired on Kabul daily[5], killing many civilians. Pakistan, Iran, Uzbekistan and Saudi Arabia played a central role in the war fighting for influence over Afghanistan. Pakistan supported Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Iran supported the Hezb-i Wahdat under Abdul Ali Mazari and Karim Khalili, Uzbekistan supported Rashid Dostum and his militia Junbish-i Milli, and Saudi Arabia supported Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami. Massoud, who was considered too independent by outside powers, had close to none outside support while he had strong support inside Afghanistan.

During the war most of Kabul was destroyed and the civilian population was harmed. The Afghanistan Justice Project provides some information on those crimes. When Hekmatyar failed to achieve what Pakistan wanted, in 1994 they turned towards a new force coming up in the southern city of Kandahar: the Taliban. With the strong support of Pakistan and later Saudi financed Osama Bin Laden [verification needed] the Taliban proceeded to Kabul, where at first Massoud handed them their first major defeat.

Some months later, however, as defense minister of the Afghan government, Massoud ordered a retreat from Kabul on September 26, 1996, after Taliban forces encircled the capital.[25]. Massoud and his troops retreated to the Northeast of Afghanistan.[26][27][28]

Resisting the Taliban (1996-2001)

As the Taliban took control of approximately 90 percent of Afghanistan, Massoud formed an alliance, called the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan. The alliance consisted of mainly Tajiks, but also had sizable numbers of Uzbeks, Hazaras, and Pashtuns. Warlords like Haji Rahim, Commander Piram Qol, Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq, General Dostum, Qazi Kabir Marzban, Commander Ata Mohammad and General Malik joined forces for their cause. From the east were Haji Abdul Qadir, Commander Hazrat Ali, Commander Jaan Daad Khan and Abdullah Wahedi. From the northeast areas, Commander Qatrah and Commander Najmuddin participated. From the southern provinces, there were Commander Qari Baba, Noorzai, and Hotak. From the western and southwest provinces came General Ismail Khan, Doctor Ibrahim, and Fazlkarim Aimaq. From central Afghanistan Commander Anwari, Said Hussein Aalemi Balkhi, Said Mustafa Kazemi, Akbari, Mohammad Ali Jawed, Karim Khaili, Commander Sher Alam, and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf (whose role remains unclear since he maintained good relations to Osama Bin Laden and played a role in the assassination of Massoud) were members of this union. Massoud provided shelter to those fleeing the Taliban. In contrast to the areas under Taliban control, in the areas under his control girls were allowed to go to school and women were allowed to work.

International relations

The United States had CIA agents working alongside Massoud, but their only interest was a joint effort to capture Osama bin Laden following the 1998 embassy bombings.[29] The U.S. and the European Union provided close to none support to the anti-Taliban fighters. A change of policy regarding a new quality of support for Massoud was underway in 2001 when it was already too late.

After the Taliban had publicly executed Mohammed Najibullah, Massoud and the United Front received increasing assistance from India.[30] India was particularly concerned about the Islamic militancy in its neighborhood and consequently provided substantial aid to the Northern Alliance—US$70 million in aid including two Mi-17 helicopters, three additional helicopters in 2000 and US$8 million worth of high-altitude equipment in 2001.[31] Furthermore, the alliance supposedly also received aid from Iran because of their opposition to a strong Sunni Taliban government, Russia and Tajikistan.[citation needed]

In April 2001, Nicole Fontaine invited Massoud to address the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium. In his speech, Massoud warned that the Taliban had connections with al-Qaeda and that he believed an important terrorist attack was imminent.[32] He also asked for humanitarian aid for the people of Afghanistan.

Death

Massoud, then aged 48, was the target of a successful suicide attack at Khwaja Bahauddin, in Takhar Province in northeastern Afghanistan on September 9, 2001 [33][34]. The attackers' names were alternately given as Dahmane Abd al-Sattar, husband of Malika El Aroud, and Bouraoui el-Ouaer; or 34-year-old Karim Touzani and 26-year-old Kacem Bakkali.[35]

The attackers claimed to be Belgians originally from Morocco. However, their passports turned out to be stolen and their nationality was later determined to be Tunisian. The assassins claimed to want to interview Massoud and then, while asking Massoud questions, set off a bomb in the camera, killing Massoud. Investigators later claimed that Jerôme Courtailler provided forged documents to the attackers.[36]

The explosion also killed Mohammed Asim Suhail, a Northern Alliance official, while Mohammad Fahim Dashty and Massoud Khalili were injured. The assassins may have intended to attack several Northern Alliance council members simultaneously.[citation needed] Bouraoui was killed by the explosion and Dahmane was captured and shot while trying to escape. Massoud was rushed after the attack to the Indian Military hospital at Farkhor, Tajikistan, which is now Farkhor Air Base.

Following the assassination, Osama bin Laden had an emissary deliver a cassette of Dahmane speaking of his love for his wife and his decision to blow himself up as well as $500 in an envelope to settle a debt, to the assassin's widow.[37]

Despite initial denials by the United Front, news of Massoud's death was reported almost immediately, appearing on the BBC, and in European and North American newspapers on September 10, 2001. However, the news was quickly overshadowed by the September 11, 2001 attacks the following day, which appeared to be the terrorist attack that Massoud had warned against in his speech to the European Parliament several months earlier.

The timing of the assassination, two days before the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, is considered significant by commentators who believe Osama bin Laden ordered the assassination to help his Taliban protectors and ensure he would have their protection and co-operation in Afghanistan. The assassins are also reported to have shown support for bin Laden in their questioning of Massoud. The Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Mujahideen leader Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, an Afghan Wahhabi Islamist, have also been mentioned as possible organizers or collaborators of the Massoud assassins.[38] Massoud was a strong opponent of Pakistani involvement in Afghanistan. The assassins are said to have entered Northern Alliance territory under the auspices of the Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and had his assistance in bypassing "normal security procedures."[38]

Immediately after the assassination there was speculation that the Northern Alliance would fall apart. But two days later, the terrorist attacks against the United States occurred, which aftermath led to the massive American support to the Afghan anti-Taliban coalition, Operation Enduring Freedom and the ousting of the Taliban from Kabul and their unofficial capital Kandahar.

On September 16, the United Front announced that Massoud had died of injuries in the suicide attack. Massoud was buried in his home village of Bazarak in the Panjshir Valley.[39] The funeral, although happening in a rather rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of people. Sad day (video clip).

In April 2003, the Karzai administration announced the setup of a commission to investigate the assassination of Massoud, as the country celebrated the 11th anniversary of the defeat of the Communist government[40]

The French secret service revealed on October 16, 2003 that the camera used by Massoud's assassins had been stolen in December 2000 in Grenoble, France from a photojournalist, Jean-Pierre Vincendet, who was then working on a story on that city's Christmas store window displays. By tracing the camera's serial number, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation was able to determine that Vincendet was its original owner. The French secret service and the FBI then began working on tracing the route the camera took between the time it was taken from Vincendet and the Massoud assassination.[41]

Legacy

National Hero

In 2001, the Afghan Interim Government under president Hamid Karzai awarded Massoud the title of "Hero of the Afghan Nation". Massoud is the subject of Ken Follett's Lie Down With Lions, a novel about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He also plays a significant role in James McGee's thriller Crow's War. Many documentaries, books and movies have been made about Ahmad Shah Massoud. One of the most notable is Fire by Sebastian Junger. Junger was one of the last Western journalists to interview Massoud in depth. The bulk of this interview was first published in March 2001 for National Geographic's Adventure Magazine, along with photographs by the renowned Iranian photographer Reza Deghati.

Lion of Panjshir

Massoud's nickname, the "Lion of Panjshir", is a rhyme and play on words in Persian, which alludes to the strength of his resistance against the Soviet Union, the mythological exaltation of the lion in Persian literature, and finally, the place name of the Panjshir Valley, where Massoud was born. The place name of "Panjshir" Valley in Persian means (Valley of the) Five Lions. Thus, the phrase "Lion of Panjshir", which in Persian is "Shir-e-Panjshir," is a rhyming play on words.

The Path to 9/11

The well-known French musician-songwriter-author Damien Saez wrote a song called "Massoud" in 2002. Massoud also was featured in the ABC Television mini-series The Path to 9/11, which aired commercial-free in the USA in 2006, on the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. The mini-series depicts Massoud warning U.S. intelligence agents of the coming U.S. attack by al-Qaeda[42] and Massoud's September 9, 2001 assassination.[43]

Personal

Massoud was married to Sediqa Massoud. They have one son (Ahmad born in 1989) and five daughters (Fatima born in 1992, Mariam born in 1993, Ayesha born in 1995, Zohra born in 1996 and Nasrin born in 1998). His wife and his children live in Iran.

The family has a great deal of prestige in the politics of Afghanistan. Of his six brothers, Ahmad Zia Massoud was a vice-president of Afghanistan under Hamid Karzai and Ahmad Wali Massoud is Afghanistan's ambassador to the United Kingdom. There have been unsuccessful attempts on the life of Ahmad Zia Massoud in late 2009.

After his death, Massoud was interred in a mausoleum in Panjshir Valley. A larger mausoleum is currently being constructed to replace the current one.

See also

Further reading

- Marcela Grad: Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader Webster University Press (2009) (recommended)

- Sediqa Massoud with Chékéba Hachemi and Marie-Francoise Colombani: Pour l'amour de Massoud (in French) (recommended)

- Stephen Tanner: Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the Fall of the Taliban

- Christophe de Ponfilly: Massoud l'Afghan (in French)

- Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 9, 2001 Penguin Press, 695. ISBN 1-59420-007-6.

- Peter Bergen: Holy War, Inc.

- Ahmed Rashid: TALIBAN - The Story of the Afghan Warlords. ISBN 0-330-49221-7.

- A. R. Rowan: On The Trail Of A Lion: Ahmed Shah Massoud, Oil Politics and Terror

- Ken Follett: Lie Down With Lions

- James McGee: Crow's War

- Roger Plunk: The Wandering Peacemaker

- References to Masood appear in the book A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

- MaryAnn T. Beverly: From That Flame (2007, Kallisti Publishing)

- Gary C. Schroen, 2005, ""First In" An Insiders Account of How The CIA Spearheaded the War on Terror in Afghanistan", New York: Presido Press/Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-89141-872-6.

External links

- Massoud's Letter To The People Of America 1998

- MEANWHILE : Remembering Massoud, a fighter for peace"

- The Assassination of Ahmad Shah Massoud Paul Wolf, Global Research, September 14, 2003

- AhmadShahMassoud.com

- Jawedan.com (Pashtu, Persian & English)

- 60 Years of Asian Heroes: Ahmad Shah Massoud Time, 2006

- Profile: Afghanistan's 'Lion Of Panjshir' Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 5, 2006

- The Last Interview with Ahmad Shah Massoud Piotr Balcerowicz, early August 2001

- "Breakfast with Massoud" by Roger Plunk The Source, December 1, 2001

- Bharat Rakshak Monitor - Ahmad Shah Mas’ud (1953-2001)

- Proposal for Peace, promoted by Commander Massoud, in English in Dari (Persian)

- Ahmad Shah Massoud at Curlie

- Massoud, l'Afghan (documentary film)

- New York Times Film Review

- rottentomatoes.com Film Review

- Theatrical Release

- Ahmad Shah Massoud, destiny's Afghan by Iqbal Malhotra

- The Lion Of Panjshir (Symphony No. 2) for narrator and symphonic band by composer David Gaines

- From That Flame (historical fiction)

- Photographs

Notes and references

- ^ Latham, Judith (March 12, 2008). "Author Roy Gutman Talks About What Went Wrong in the Decade Before 9/11 Attacks", Voice of America News.

- ^ Afghanistan Events, Lonely Planet Travel Guide.

- ^ Shehzad, Mohammad (May 22, 2002). "Warrior and Peace", The News on Sunday (Karachi).

- ^ Accueil

- ^ a b Biography: Lion of Panjshir Ahmad Shah Massoud.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (1990). Islam and resistance in Afghanistan. Cambridge University Press, p.76. ISBN 0-521-39700-6

- ^ Roy p. 102.

- ^ "Biography: Ahmad Shah Massoud", http://www.afgha.com/, August 31, 2006.

- ^ Isby, David (1989). War in a distant country, Afghanistan: invasion and resistance. Arms and Armour Press. p. 107. ISBN 0 85368 769 2.

- ^ "The Reagan Doctrine, 1985", United States State Department.

- ^ a b van Voorst, Bruce; Iyer, Pico; Aftab, Mohammad (May 7, 1984). "Afghanistan: The bear descends on the lion". Time. New York.

- ^ Roy, p.199.

- ^ Roy, p.201.

- ^ Roy, p.213.

- ^ Isby, p.98.

- ^ Roy, p.202.

- ^ Barry, Michael (2002). Massoud, de l'islamisme à la liberté, p. 216. Paris: Audibert. Template:Language icon ISBN 2-84749-002-7

- ^ Bowersox, Gary; Snee, Lawrence; Foord, Eugene; Seal, Robert (1991). "Emeralds of the Panjshir valley, Afghanistan". www.gems-afghan.com. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Le pouvoir des seigneurs de guerre et la situation sécuritaire en Afghanistan" (PDF) (in French). Commission des Recours des Réfugiés. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Davies, L. Will; Shariat, Abdullah (2004). Fighting Masoud's war, Melbourne: Lothian, p. 200. ISBN 0-7344-0590-1

- ^ Barry, p.194.

- ^ Phillips, James A. (May 18, 1992). "Winning the Endgame in Afghanistan", Heritage Foundation Backgrounder #181.

- ^ Johns, Michael (January 19, 2008). "Charlie Wilson's War Was Really America's War" (blog).

- ^ a b c d e The Fall of Kabul, April 1992, Library of Congress country studies. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- ^ "As the Taliban Finish Off Foes, Iran Is Looming"

- ^ "Afghan 'Lion' Fights Taliban With Rifle and Fax Machine"

- ^ "Afghan Driven From Kabul Makes Stand in North"

- ^ Risen, James. "State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration", 2006

- ^ Peter Pigott: Canada in Afghanistan

- ^ Duncan Mcleod: India and Pakistan

- ^

"April 6, 2001: Rebel Leader Warns Europe and US About Large-Scale Imminent Al-Qaeda Attacks". History Commons. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Taliban Foe Hurt and Aide Killed by Bomb"

- ^ "THREATS AND RESPONSES: ASSASSINATION; Afghans, Too, Mark a Day of Disaster: A Hero Was Lost"

- ^ Pinto, Maria do Ceu. "Islamist and Middle Eastern Terrorism: A Threat to Europe?". p. 72.

- ^ Vidino, Lorenzo. "Al-Qaeda in Europe", 2006. Prometheus Books

- ^ "Suicide Bomber's Widow Soldiers On" http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/asiapcf/08/15/elaroud/index.html

- ^ a b Anderson, Jon Lee (June 10, 2002). "The assassins", The New Yorker, Vol.78, Iss. 15; p. 72.

- ^ "Rebel Chief Who Fought The Taliban Is Buried"

- ^ "AFTEREFFECTS: Briefly Noted; AFGHAN PANEL TO INVESTIGATE MASSOUD'S DEATH"

- ^ "TV camera rigged to kill Afghan rebel Masood stolen in France: police", Agence France-Presse, October 16, 2003.

- ^ Ahmad Shah Massoud's warning to the United States, The Path to 9/11 (video clip).

- ^ Assassination of Ahmad Shah Massoud, The Path to 9/11.

- 1953 births

- 2001 deaths

- National hero

- Commander

- Tajik people

- Afghan anti-communists

- Assassinated Afghan politicians

- Assassinated military personnel

- Cold War leaders

- Deaths by explosive device

- Government ministers of Afghanistan

- Guerrilla warfare theorists

- Military personnel killed in action

- People involved in the Soviet war in Afghanistan

- People murdered in Afghanistan