Globe

A globe is a three-dimensional scale model of Earth (terrestrial globe) or other spheroid celestial body such as a planet, star, or moon. It may also refer to a spherical representation of the celestial sphere, showing the apparent positions of the stars and constellations in the sky (celestial globe). The word "globe" comes from the Latin word globus, meaning round mass or sphere.

Terrestrial and planetary

A globe is the only geographical representation that has negligible distortion over large areas, with the exception of the two-dimensional Dymaxion Map; all flat maps are created using a map projection that inevitably introduces an increasing amount of distortion the larger the area that the map shows. A typical scale for a terrestrial globe is roughly 1:40 million.

Sometimes a globe has relief, showing topography; in the case of a globe of the Earth the elevations are exaggerated, otherwise they would be hardly visible. Most modern globes are also imprinted with parallels and meridians so that one can (if only approximately due to scale) tell the coordinates of a specific point on the surface of the planet.

Celestial

Celestial globes show the apparent positions of the stars in the sky. They omit the Sun, Moon and planets because the positions of these bodies vary relative to those of the stars, but the ecliptic, along which the Sun moves, is indicated.

A potential issue arises regarding the "handedness" of celestial globes. If the globe is constructed so that the stars are in the positions they actually occupy on the imaginary celestial sphere, then the star field will appear back-to-front on the surface of the globe (all the constellations will appear as their mirror images). This is because the view from Earth, positioned at the centre of the celestial sphere, is of the inside of the celestial sphere, whereas the celestial globe is viewed from the outside. For this reason, celestial globes may be produced in mirror image, so that at least the constellations appear the "right way round". Some modern celestial globes address this problem by making the surface of the globe transparent. The stars can then be placed in their proper positions and viewed through the globe, so that the view is of the inside of the celestial sphere, as it is from Earth.

History

The sphericity of the Earth was established by Hellenistic astronomy in the 3rd century BCE, and the earliest terrestrial globe appeared from that period. The earliest known example is the one constructed by Crates of Mallus in Cilicia (now Çukurova in modern-day Turkey), in the mid-2nd century BCE.[1]

No terrestrial globes from Antiquity or the Middle Ages have survived. An example of a surviving celestial globe is part of a Hellenistic sculpture, called the Farnese Atlas, surviving in a 2nd century AD Roman copy in the Naples Museum, Naples, Italy.[2]

Early terrestrial globes depicting the entirety of the Old World were constructed in the Islamic Golden Age. One such example was constructed in the 9th century by Muslim geographers and cartographers working under the Abbasid caliph, Al-Ma'mun.[3][4] Another example was the terrestrial globe introduced to Beijing by the Persian astronomer, Jamal ad-Din, in 1267.[5]

The oldest surviving terrestrial globe is credited to Martin Behaim in Nürnberg, Germany, in 1492.[2] A facsimile globe showing America was made by Martin Waldseemueller in 1507. Another early globe, the Hunt-Lenox Globe, ca. 1507, is thought to be the source of the phrase "Here be dragons." Another "remarkably modern-looking" terrestrial globe of the Earth was constructed by Taqi al-Din at the Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din during the 1570s.[6]

An unusually high proportion of vintage 20th century world globes feature the Australian town of Birdum, which no longer exists but once held an important position at the end of the Northern Australian Railway.

Manufacture

Mass-produced globes are typically covered by a printed paper map. The most common type has long, thin gores (strips) of paper that narrow to a point at the North Pole and the South Pole.[7] Then a small disk is used to paper over the inevitable irregularities at the poles. The more gores there are, the less stretching and crumpling is required to make the paper map fit the sphere. From a geometric point of view, all points on a sphere are equivalent – one could select any arbitrary point on the Earth, and create a paper map that covers the Earth with strips that come together at that point and the antipodal point.

A globe is usually mounted at a 23.5° angle on bearings. In addition to making it easy to use this mounting also represents the angle of the planet in relation to its sun and the spin of the planet. This makes it easy to visualize how days and seasons change.

Notable examples

- The Unisphere in Queens, New York, at 120 feet (36.6 meters) in diameter, is the world's largest global structure.

- Eartha, currently the world's largest rotating globe (41 feet in diameter), at the Delorme headquarters in Yarmouth, Maine

- The Mapparium, three-story, stained glass globe at the The Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston, which visitors walk through via a 30 foot glass bridge.

- The Babson globe in Wellesley, Massachusetts, a 26-foot-diameter (7.9 m) globe which originally rotated on its axis and on its base to simulate day and night and the seasons

- The giant globe in the lobby of The News Building in New York City.

- The Hitler Globe, also known as the Führer globe, was formally named the Columbus Globe for State and Industry Leaders. Two editions existed during Hitler's lifetime, created during the mid-1930s on his orders. (The second edition changed the name of Abyssinia to Italian East Africa). These globes were "enormous" and very costly. According to the New York Times, "the real Columbus globe was nearly the size of a Volkswagen and, at the time, more expensive." Several still exist, including three in Berlin: one at a geographical institute, one at the Märkisches Museum, and another at the Deutsches Historisches Museum. The latter has a Soviet bullet hole through Germany. One of the two in public collections in Munich has an American bullet hole through Germany. There are several in private hands inside and out of Germany. A much smaller version of Hitler's globe was mocked by Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator, a film released in 1940.[8]

Gallery

-

Top view of 1765 de l'Isle globe

-

The Unisphere, attributed to "uribe"/Uri Baruchin

-

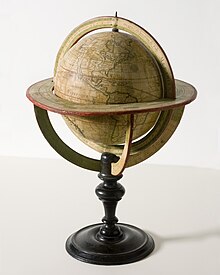

1594, Mechanised Celestial Globe

-

A globe displayed in the old library of the University of Salamanca.

-

An animated globe (based on images from NASA)

-

A 'global view map' of Europe, Arabia and Africa.

See also

- Armillary sphere

- Cartography

- Dymaxion map

- Emery Molyneux

- Google Earth

- NASA World Wind

- Johannes Schöner globe

- Virtual globe

References

- ^ Earth Globe

- ^ a b Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 2003.

- ^ Medieval Islamic Civilization By Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach, page 138-139 - available via google books - http://books.google.com/books?id=H-k9oc9xsuAC&pg=PA138&lpg=PA138&dq=al-Ma%3Fmun%3Fs+globe&source=bl&ots=TSmSiEUZXk&sig=NGzhTsbRRoSmH4UiPQCh0Y1sO_c&hl=en&ei=NMxYSvbsBeS6jAfNjNwa&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8

- ^ Covington, Richard (2007), Saudi Aramco World, May-June 2007: 17–21 http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200703/the.third.dimension.htm, retrieved 2008-07-06

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ David Woodward (1989), "The Image of the Spherical Earth", Perspecta, 25, MIT Press: 3–15 [9], retrieved 2010-02-22

- ^ Soucek, Svat (1994), "Piri Reis and Ottoman Discovery of the Great Discoveries", Studia Islamica, 79, Maisonneuve &: 121–142 [123 & 134–6], doi:10.2307/1595839

- ^ http://netpbm.sourceforge.net/doc/globe.jpg

- ^ "The Mystery of Hitler's Globe Goes Round and Round", by Michael Kimmelman, September 18, 2007. Accessed September 18, 2007.