King Charles Spaniel

| King Charles Spaniel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Other names | English Toy Spaniel, Toy Spaniel, Charlies, Prince Charles Spaniel, Ruby Spaniel, Blenheim Spaniel, Holland Spaniel | ||||||||

| Origin | England | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||

The King Charles Spaniel (also known as the English Toy Spaniel) is a breed of small dog of the Spaniel type. Prior to the 20th century, there were four varieties which made up the Toy Spaniel type; these were the Blenheim Spaniel, the Prince Charles Spaniel, the Ruby Spaniel and the aforementioned King Charles Spaniel. In 1903 The Kennel Club (UK) amalgamated these four breeds under the single title of the King Charles Spaniel. Each of the former breeds contributes one of the four colours available in the breed.

Thought to have originated in the Far East, these types of spaniels were seen in Europe in Italy in the 16th century. They were made famous by association with Charles II of England. The King Charles Spaniel and the other types of Toy Spaniels were crossbred with the Pug in the early 18th century in order to reduce the size of the nose, as was the style of the day. The 20th century saw attempts to restore lines of King Charles Spaniels to the type seen during Charles II's time. These attempts included the unsuccessful Toy Trawler Spaniel and the now popular Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. The Cavalier is slightly larger, with a flat head and a longer nose, while the "Charlie" is smaller, with a domed head and flat face. The breed is prone to several health problems, including cardiac conditions and a range of eye issues.

Historically they may have been used in hunting; however, due to their stature they were not well suited to it. Today they keep their hunting instincts, but are not high energy and are more suited to being a lapdog. They have continued to be linked to royalty since the 16th century, and members of the breed have been owned by Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia, Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II.

History

The fact that dogs are always part of a royal Japanese present suggested to the Commodore the thought that possibly one species of spaniel now in England may be traced to a Japanese origin. In 1613, when Captain Saris returned from Japan to England, he carried to the King a letter from the Emperor, and presents in return for those sent to him by his Majesty of England. Dogs probably formed part of the gifts and thus may have been introduced into the Kingdom the Japanese breed. At any rate, there is a species of Spaniel in England which it is hard to distinguish from the Japanese dog. The species sent by the Emperor is by no means common even in Japan. It is never seen running about the streets, or following its master in his walks, and the Commodore understood that they were costly.

Francis L. Hawks and Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1856)[1]

It is thought that the types of spaniels which eventually became the King Charles Spaniel originated in the Far East, primarily Japan, with the dogs as gifts made to European royalty,[2] and may share a common ancestry with the Pekingese and Japanese Chin.[3] The red and white type of toy spaniel were first seen in paintings by Titian around 1505. Further paintings featuring these types of spaniels were created by Palma Vecchio and Paolo Veronese during the early part of the 16th century. These dogs already had a high domed head with a short nose, although it was more pointed than in the present day. These Italian toy spaniels may have been crossed with local small dogs such as the Maltese and also with imported Chinese dogs.[4] The Papillon is the continental descendant of these same types of toy-sized spaniels.[5]

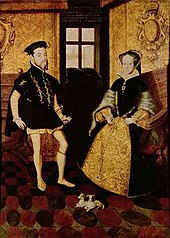

The earliest recorded appearance of a toy spaniel in England during the period prior to Charles II was that of a painting attributed to Antonis Mor of Philip II of Spain and Mary I of England, painted in 1552.[6] Mary, Queen of Scots also had a fondness for small toy dogs, including spaniels,[7] showing the connection between these types of dogs and the English Royalty before the monarch from which they would eventually take their name.[6]

Henry III of France owned a number of small spaniels, which were called Damarets.[8] Although one of the translations of John Caius' 1576 work Of Englishe Dogges talks of "a new type of Spaniel brought out of France, rare, strange, and hard to get",[8] this was actually an addition by a later translation and is not in the original Latin.[8] Captain John Saris may have brought back examples of toy spaniels from his voyage to Japan in 1613.[3] During Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expeditions to Japan on behalf of the United States in the mid-19th century, he noted that dogs were a common gift and that it was likely that the earlier voyage of Captain Saris introduced a Japanese type of spaniel into England.[1]

Charles II and the 17th century

In the 17th century, these dogs began to appear in paintings by Dutch artists such as Caspar Netscher and Peter Paul Rubens. Spanish artists, including Juan de Valdés Leal and Diego Velázquez, also featured these types of dogs. French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon would later describe these types of dogs as being a cross between a spaniel and the Pug.[5] The dogs featured in the Spanish paintings were exclusively tricolor, black and white or entirely white.[5]

Charles I of England can be seen in paintings with types of cocker/cocking spaniels. The Sporting Directory (1804) says of these dogs: "These do not appear to have been the small black kind known by his name, but Cockers, as is evident from the pictures of Van Dyck and the print by Sir R. Strange, after this master, of three of his children, in which they are introduced."[9]

Toy spaniels became a preferred pet lap dog in Europe, with each family having its favourite. Charles II was very fond of this type of dog, which is why the dogs of today carry his name,[10] although there is no evidence that today's breed descended from his particular dogs. Samuel Pepys's diary describes how the spaniels could roam anywhere in Whitehall Palace, even during state occasions.[10] One example of an entry in his diary regarding these dogs is from 1 September 1666 when Pepys was discussing a council meeting, "All I observed there was the silliness of the King, playing with his dog all the while and not minding the business."[11] Charles' sister Princess Henrietta has also been painted by Pierre Mignard holding a small red and white toy-sized spaniel,[12] and it is thought that after her death at the age of 26 in 1670 that Charles took over her group of dogs for himself.[12]

18th and 19th centuries

During the 18th century, the Maltese was considered to be a type of spaniel, and thought to be the parent breed of toy spaniels, including both the King Charles and the Blenheim varieties.[13] The varieties of toy spaniel were occasionally used in hunting, as the Sportsman's Repository reports in 1830 of the Blenheim Spaniel; "Twenty years ago, His Grace the Duke of Marlborough was reputed to possess the smallest and best breed of cockers in Britain; they were invariably red-and-white, with very long ears, short noses, and black eyes."[13] During this period the term "cocker" was not used to describe a Cocker Spaniel, but a type of small spaniel used to hunt woodcock. The Duke's residence, Blenheim Palace, gave its name to the Blenheim Spaniel. The Sportsman's Repository goes on to explain that the toy spaniels are able to hunt, albeit not for a full day or in difficult terrain; "The very delicate and small, or 'carpet spaniels,' have exquisite nose, and will hunt truly and pleasantly, but are neither fit for a long day or thorny covert."[14] This idea was supported by Vero Shaw in his 1881 work The Illustrated Book of the Dog,[14] and by Thomas Brown in 1829 who wrote, "He is seldom used for field-sports, from his diminutive size, being easily tired, and is too short in the legs to get through swampy ground."[15]

They were often compared to the Pug in popularity as lap dogs for ladies. The disadvantage of the breeds of toy spaniel were that their long coats required constant grooming.[13] By 1830, the toy spaniel had changed somewhat from the dogs of Charles II's day. Due to the fashion of the period, the toy spaniels were crossed with Pugs in order to reduce the size of the noses of the breeds and then bred by breeders to reduce it further. By doing this, the dog's sense of smell was impaired and according to 18th century writers this caused the varieties of toy spaniel to be removed from participation in field sports.[14] However, Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, writing in her 1911 work Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors, proposes that the red and white Blenheim Spaniels always had the shorter nose now seen in the modern King Charles.[4] In 1860, the average price of a Blenheim Spaniel was about £15,[16] equivalent to around £1420 in 2011 when adjusted for inflation.[17]

At the turn of the 19th century, it was the fashion for ladies to carry small toy-sized spaniels as they traveled around town. These dogs were called "Comforters" and given the species biological classification of Canis consolator by 19th century dog writers. By the 1830s, as this practice was no longer in vogue, these types of spaniels were becoming rarer.[18] "Comforter" was given as a generic term to both the English Toy and Continental Toy Spaniels, the latter of which was similar to the modern Phalène.[19] It was thought that the dogs held some type of healing properties, as written in 1829, "these little dogs are good to asswage the sickness of stomach, being oftentimes thereunto applied as a plaister preservative, or bourne in the bosum of the diseased and weak person, which effect is performed by their moderate heat."[20] By the 1840s, "Comforter" had dropped out of use, and they had returned to being called Toy Spaniels.[21] The first written occurrence of a ruby coloured toy spaniel was a dog named Dandy, owned by a Mr Garwood in 1875.[22]

There was scandal at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show in 1895 when eight of Mrs F Senn's show dogs were poisoned by an unknown assailant. These dogs included the two King Charles Spaniels, King of the Charlies and Lady de Lena, and the Prince Charles Spaniel Belle. King of the Charlies had won the challenge class at Westminster in 1894.[23]

The dogs continued to be popular with royalty, Queen Victoria's first dog was a King Charles Spaniel named Dash.[24] In 1896, Otto von Bismarck purchased a King Charles Spaniel from an American kennel for $1,000. The dog weighed under 2 pounds (0.91 kg), and had been disqualified from the Westminster Kennel Club in the previous year on account of its weight.[25]

Conformation showing and the 20th century

In 1903, The Kennel Club attempted to amalgamate the King James (black and tan), Prince Charles (tricolour), Blenheims and Ruby spaniels into a single breed called the Toy Spaniel. The Toy Spaniel Club which oversaw those separate breeds strongly objected, and the argument was only resolved following the intervention of King Edward VII who made it clear that he preferred the name "King Charles Spaniel".[26] In 1904, the American Kennel Club followed suit, combining the four breeds into a single breed known as the English Toy Spaniel.[2]

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia owned a King Charles Spaniel at the time of the shooting of the Romanov family on 17 July 1918. Nicholas Sokolov of the White Forces found a clearing some eight days later where he believed the bodies of the Romanov family had been burnt. He discovered the corpse of a King Charles Spaniel amongst the items at the site.[27]

Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth, documented her attempts in the early 20th century to re-breed the 18th century type of King Charles Spaniel as seen in the portraits of King Charles II.[28] She used the Toy Trawler Spaniel, a curly haired, mostly black, small to medium sized spaniel, and cross-bred these dogs with a variety of breeds, including Blenheim Spaniels and Cocker Spaniels, in unsuccessful attempts to reproduce the earlier style.[22]

The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel originated from a competition held by American Roswell Eldridge in 1926. He offered a prize fund of £25 for the best male and female dogs of "Blenheim Spaniels of the old type, as shown in pictures of Charles II of England's time, long face, no stop, flat skull, not inclined to be domed, with spot in centre of skull."[29] Breeders entered what they considered to be sub-par King Charles Spaniels, and although Eldridge did not live to see the new breed created, several breeders banded together and created the first breed club for the new Cavalier King Charles Spaniel in 1928; with The Kennel Club (UK) initially listing the new breed as "King Charles Spaniels, Cavalier type". In 1945 the Kennel Club recognised the new breed in it's own right.[29] The American Kennel Club did not recognise the Cavalier until 1997.[30]

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon continued the connection between royalty and the King Charles Spaniel, attending Princess Anne's tenth birthday party with her dog Rolly in 1960.[31][32] Elizabeth II has also owned King Charles Spaniels in addition to the dogs most frequently associated with her, the Welsh Corgi.[33]

In 2008, the BBC broadcast Pedigree Dogs Exposed, which was critical of the breeding of a variety of pedigree breeds, including the King Charles Spaniel. The show highlighted issues involving syringomyelia in both the King Charles and the Cavalier breeds. Mark Evans, the chief veterinary advisor for the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) said, "Dog shows using current breed standards as the main judging criteria actively encourage both the intentional breeding of deformed and disabled dogs and the inbreeding of closely related animals";[34] this opinion was seconded by the Scottish SPCA.[34] Following the programme, the RSPCA pulled its sponsorship of Crufts,[35] and the BBC declined to broadcast coverage of the event.[36]

The King Charles Spaniel is less popular than the Cavalier variety in both the UK and America. In 2010 the Cavalier was the 23rd most popular breed according to registration figures collected by the American Kennel Club, while the English Toy Spaniel was the 126th.[37] In the UK, according to the Kennel Club, the Cavalier is the most popular breed in the Toy Group with 8,154 puppies registered in 2010, while the King Charles Spaniel had 199.[38] Due to the low number of registrations, the King Charles was identified as a Vulnerable Native Breed by the Kennel Club in 2003 in order to help promote the breed.[39]

Description

The King Charles has large dark eyes, a short nose, a high domed head and a black margin around its lips.[7] It stands on average 9–11 inches (23–28 cm) at the withers, with a small but compact body.[40] The breed has a traditionally docked tail.[41] The breed has the long pendulous ears typical of a spaniel and its coat comes in four varieties which it shares with its offshoot, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.[40][42]

These four sets of markings reflect the four former breeds from which the modern breed combined; black and tan markings are known as "King Charles", while "Prince Charles" is tricolored, "Blenheim" is red and white, and finally "Ruby" is a single colored solid rich red.[40] The "King Charles" black and tan markings typically has a black coat with mahogany/tan markings on the face, legs and chest and under the tail. The tricolored "Prince Charles" is mostly white with black patches, and mahogany/tan markings in similar locations to the "King Charles" markings. "Blenheim" has a white coat with red patches, and should have a distinctive red spot in the middle of the forehead.[43][44]

The King Charles Spaniel and the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel can be often confused with each other. There are several significant differences between the two breeds, with the primary difference being the size.[29] While the Cavalier weighs on average between 13 to 18 pounds (5.9 to 8.2 kg),[42] the King Charles is smaller at 8 to 14 pounds (3.6 to 6.4 kg).[40] In addition their facial features, while similar, are different: the Cavalier's ears are set higher and its skull is flat while the King Charles's is domed. Finally, the muzzle length of the King Charles tends to be shorter than the typical muzzle on a Cavalier.[29]

The American Kennel Club has two classes: English Toy Spaniel (B/PC) (Blenheim and Prince Charles) and English Toy Spaniel (R/KC),[2] while in the UK the Kennel Club has the breed in a single class.[45] Under the Fédération Cynologique Internationale groups, the King Charles is placed in the English Toy Spaniel section within the Companion and Toy Dog Group along with the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.[46]

Temperament

The King Charles is a friendly breed, to the extent that typically it is not as adept at being a watchdog as some breeds,[40] but may still bark to warn its owners of an approaching visitor.[7] It is not a high energy breed, and enjoys the company of family members,[40] being primarily a lapdog.[7] They prefer not to be left alone for long periods of time and will not accept rough handling. Known as one of the quietest of the toy breeds, it is suitable for apartment living.[40]

The breed can tolerate other pets well,[40] although the King Charles still has the hunting instincts of its historic predecessors and may not always be friendly towards smaller animals.[2] Although tolerant of and able bond well with children, those children must learn to be gentle with members of this breed.[40] The breed is clever enough to be used for obedience work, and due to their stable temperament, they can be successful visiting dogs for hospitals and nursing homes.[7]

Health

The King Charles Spaniel has several associated health conditions, including eye problems such as cataracts, corneal dystrophy, distichia, entropion, microphthalmia, optic disc drusen, and keratitis. Of these conditions, distichia is considered more common than the other conditions, and the breed is at an increased risk compared to other breeds. Inheritance is suspected in the other conditions, with varying ages of onset ranging from six months in cataracts to two to five years with corneal dystrophy.[47]

Heart conditions related to the King Charles Spaniel include mitral valve disease, a condition where the mitral valve degrades causing blood to flow backwards through the chambers of the heart and eventually leading to congestive heart failure.[48][49] Patent ductus arteriosus, where blood is channeled back from the heart into the lungs, is also seen and is another disease that can lead to heart failure.[50] Both of these conditions present with similar symptoms and are inheritable.[49][50] Being a short-nosed breed, King Charles Spaniels can be sensitive to anesthesia.[51]

In surveys conducted by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals, the King Charles Spaniel placed 38th worst out of 99 breeds for patella luxation; out of 75 animals tested, 4% were found to have the ailment.[52] Out of 105 breeds, it placed 7th worst for cardiac disease, with 189 animals checked and 2.1% found to be affected.[53] They have an average lifespan of just over ten years.[54]

References

- Specific

- ^ a b Hawks, Francis L. (1856). Narrative of the expedition of an American squadron to the China Seas and Japan. Washington, D.C.: Beverley Tucker. p. 369.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "English Toy Spaniel Did You Know?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 94

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 14

- ^ a b c Lytton (1911): p. 15

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 38

- ^ a b c d e Rice, Dan (2002). Small Dog Breeds. Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0764120954.

- ^ a b c Lytton (1911): p. 16

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 18

- ^ a b Shaw (1881): p. 162

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 52

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 17

- ^ a b c Shaw (1881): p. 163

- ^ a b c Shaw (1881): p. 164

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 295

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 25/

- ^ "Inflation Calculator". Bank of England. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 301

- ^ Hungerland, Jacklyn E. (2003). Papillions. Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series. p. 6. ISBN 978-0764124198.

- ^ Brown (1829): p. 302

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 36

- ^ a b Lytton (1911): p. 40

- ^ "Prize Dogs Poisoned". The New York Times. 23 February 1895.

- ^ Longford, Elizabeth (1964). Victoria R.I. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 155. ISBN 0-297-17001-5.

- ^ "Gillie Sells For $1,000". The New York Times. 17 April 1896.

- ^ Jackson, Frank (1990). Crufts: The Official History. London: Pelham Books. p. 116. ISBN 0 7207 1889 9.

- ^ Dalley, Jan (7 January 1996). "Grave Affairs". The Independent.

- ^ Lytton (1911): p. 80

- ^ a b c d Coile (2008): p. 9

- ^ Moffat (2006): p. 23

- ^ "Princess Anne's 10th Birthday". The Glasgow Herald. 16 August 1960.

- ^ Gilmore, Eddy (29 August 1959). "Anne Happy, Phillip Miffed As Ike Leaves Family". Gadsden Times.

- ^ "Queen, Looking Well, Goes To Palace". The Evening Times. 18 January 1960.

- ^ a b Donnelly, Brian (16 September 2008). "Crufts hit by 'deformed' breeds row". The Herald.

- ^ Sugden, Joanne (15 September 2008). "RSPCA pulls out of Crufts over breeding row". The Times.

- ^ Kiss, Jemima (12 December 2008). "BBC suspends coverage of Crufts dog show after four decades". The Guardian.

- ^ "AKC Dog Registration Statistics". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Comparative Tables of Registrations For the Years 2001 - 2010 Inclusive" (PDF). The Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Hankins, Justine (19 February 2006). "The dying breeds". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Palika (2007): pp. 232-233

- ^ "Traditionally Docked Breeds". The Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b Palika (2007): p. 190

- ^ "English Toy Spaniel" (PDF). Canadian Kennel Club. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "King Charles Spaniel Breed Standard". The Kennel Club. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Breed and Class Results: King Charles Spaniel". DFS Crufts. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Breeds Nomenclature". Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Gough, Alex (2010). Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs and Cats. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 126. ISBN 978-1405180788.

- ^ "Breed Health Concerns/Research Interests". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Mitral Valve Disease". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Patent Ductus Arteriosus". American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Arden, Darleen (2006). Small Dogs, Big Hearts. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-0471779636.

- ^ "Patella Luxation Statistics". Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Cardiac Statistics". Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Choron, Sandra (2005). Planet Dog: A Doglopedia. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 162. ISBN 978-0618517527.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- General

- Brown, Thomas (1829). Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

- Coile, D. Caroline (2008). Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (2nd ed.). Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 9780764137716.

- Lytton, Mrs. Neville (1911). Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors. New York: D Appleton and Company.

- Moffat, Norma (2006). Cavalier King Charles Spaniel: Your Happy Healthy Pet (2nd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471748234.

- Palika, Liz (2007). The Howell Book of Dogs: The Definitive Reference to 300 Breeds and Varieties. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470009215.

- Shaw, Vero Kemball (1881). The Illustrated Book of the Dog. London, New York: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.