D-Wave Systems

| |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Computer hardware |

| Founded | 1999 |

| Headquarters | Burnaby, British Columbia , Canada |

Key people | Vern Brownell, CEO Geordie Rose, CTO V. Paul Lee, Chair |

| Products | Orion Web Services |

| Revenue | N/A |

| N/A | |

Number of employees | approx. 60 |

| Subsidiaries | None |

| Website | www.dwavesys.com |

D-Wave Systems, Inc. is a technology company, based in Burnaby, British Columbia. On January 19, 2007, it announced a working prototype of a potentially commercially-viable quantum computer. However, the claim that it is actually a quantum computer is disputed.[1][2]

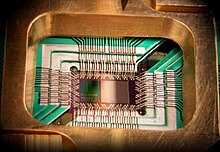

The prototype was, according to D-Wave, a 16-qubit adiabatic quantum computer, which they demonstrated on February 13, 2007 at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.[3] D-Wave demonstrated what they claimed to be a 28-qubit adiabatic quantum computer on November 12, 2007.[4] The chip was fabricated at the Jet Propulsion Lab’s microdevices lab in Pasadena.[5] During this time, D-Wave also claimed that by the end of 2008 they would have a 128-qubit system, a claim that was widely doubted due to both the lack of evidence that they are capable of creating coherent qubits at all, and that in November 2007 they only had a 28-qubit system. However, on December 19, 2008, they announced a "128 qubit" chip.[6]

Technology Description

As of June 2010, it has been published that a D-Wave processor comprises a programmable[7] superconducting integrated circuit with up to 128 pair-wise coupled[8] superconducting flux qubits.[9][10][11] The processor is designed to implement a special-purpose adiabatic quantum optimization algorithm[12][13] as opposed to being operated as a universal gate-model quantum computer.

D-Wave maintains a list of peer-reviewed technical publications on their website.[14]

History

D-Wave was founded by Haig Farris (former chair of board), Geordie Rose (CTO and former CEO), Bob Wiens (former CFO), and Alexandre Zagoskin (former VP Research and Chief Scientist). Farris taught an entrepreneurship course at UBC, where Rose obtained his Ph.D. and Zagoskin was a postdoctoral fellow. The company name refers to their first qubit designs, which used d-wave superconductors.

D-Wave operated as an offshoot from UBC, while maintaining ties with the department of Physics and Astronomy. It funded academic research in quantum computing, thus building a collaborative network of research scientists. The company collaborated with several universities and institutions, including UBC, IPHT Jena, Université de Sherbrooke, University of Toronto, University of Twente, Chalmers University of Technology, University of Erlangen, and Jet Propulsion Laboratory. These researchers worked with D-Wave scientists and engineers. Some of D-Wave's peer-reviewed technical publications come from this period. Some publications have D-Wave employees as authors, while others include employees of their partners as well or only. As of 2005, these partnerships were no longer listed on D-Wave’s website.[15][16]

D-Wave operated from various locations in Vancouver and laboratory spaces at UBC before moving to its current location in the neighboring suburb of Burnaby.

Orion

On February 13, 2007, D-Wave demonstrated the Orion system, running three different applications at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. This marked the first public demonstration of, supposedly, a quantum computer and associated service.

The first application, an example of pattern matching, performed a search for a similar compound to a known drug within a database of molecules. The next application computed a seating arrangement for an event subject to compatibilities and incompatibilities between guests. The last involved solving a Sudoku puzzle.

The processors at the heart of D-Wave's "Orion quantum computing system" are hardware accelerators designed to solve a particular NP-complete problem related to the two dimensional Ising model in a magnetic field.[3] D-Wave terms the device a 16-qubit superconducting adiabatic quantum computer processor.[6][17]

According to the company, a conventional front end running an application that requires the solution of an NP-complete problem, such as pattern matching, passes the problem to the Orion system. However, the company does not make the claim its systems can solve NP-complete problems in polynomial time.

According to Dr. Geordie Rose, Founder and Chief Technology Officer of D-Wave, NP-complete problems "are probably not exactly solvable, no matter how big, fast or advanced computers get" so the adiabatic quantum computer used by the Orion system is intended to quickly compute an approximate solution.[18]

2009 Google demonstration

On Tuesday, December 8, 2009 at the Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) conference, a Google research team led by Hartmut Neven used D-Wave's processor to train a binary image classifier.

Criticism

D-Wave has been heavily criticized by some scientists in the quantum computing field. According to Scott Aaronson, a Computer Science professor at MIT who specializes in the theory of quantum computing, D-Wave's demonstration did not prove anything about the workings of the computer. He claimed a useful quantum computer would require a huge breakthrough in physics, which has not been published or shared with the physics community.[1] Dr. Aaronson has maintained or updated his criticisms on his blog.[19] See [20] for a rebuttal of Scott Aaronson's criticisms by Dr. David Bacon, a professor at the University of Washington.

Umesh Vazirani, a professor at UC Berkeley and one of the founders of quantum complexity theory, made the following criticism:[2]

"Their claimed speedup over classical algorithms appears to be based on a misunderstanding of a paper my colleagues van Dam, Mosca and I wrote on “The power of adiabatic quantum computing”. That speed up unfortunately does not hold in the setting at hand, and therefore D-Wave’s “quantum computer” even if it turns out to be a true quantum computer, and even if it can be scaled to thousands of qubits, would likely not be more powerful than a cell phone."

Wim van Dam, a professor at UC Santa Barbara, summarized the current scientific community consensus in the journal Nature:[21]

"At the moment it is impossible to say if D-Wave's quantum computer is intrinsically equivalent to a classical computer or not. So until more is known about their error rates, caveat emptor is the least one can say."

See also

References

- ^ a b "Shtetl-Optimized: The Orion Quantum Computer Anti-Hype FAQ". 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ a b "Shtetl-Optimized: D-Wave Easter Spectacular". 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ a b "Quantum Computing Demo Announcement". 2007-01-19. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ D-Wave Systems: News

- ^ A picture of the demo chip « rose.blog

- ^ a b "WIRA Rainier 0-silicon pic". 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2008-12-25. Cite error: The named reference "adiabatic" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ M. W. Johnson et al., "A scalable control system for a superconducting adiabatic quantum optimization processor," Supercond. Sci. Technol. 23, 065004 (2010); preprint available: arXiv:0907.3757

- ^ R. Harris et al., "Compound Josephson-junction coupler for flux qubits with minimal crosstalk," Phys. Rev. B 80, 052506 (2009); preprint available: arXiv:0904.3784

- ^ R. Harris et al., "Experimental demonstration of a robust and scalable flux qubit," Phys. Rev. B 81, 134510 (2010); preprint available: arXiv:0909.4321

- ^ Next Big Future: Robust and Scalable Flux Qubit, [1], September 23, 2009

- ^ Next Big Future: Dwave Systems Adiabatic Quantum Computer [2], October 23, 2009

- ^ Edward Farhi et al., "A Quantum Adiabatic Evolution Algorithm Applied to Random Instances of an NP-Complete Problem," Science 92, 5516, p.472 (2001)

- ^ Next Big Future: Dwave Publishes Experiments Consistents with Quantum Computing and Support Claim of At Least Quantum Annealing, [3], April 09, 2010

- ^ Publications

- ^ "D-Wave Systems at the Way Back Machine". 2002-11-23. Archived from the original on 2002-11-23. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ "D-Wave Systems at the Way Back Machine". 2005-03-24. Archived from the original on 2005-03-24. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ Meglicki, Zdzislaw (2008). Quantum Computing Without Magic: Devices. MIT Press. pp. 390–391. ISBN 026213506X.

- ^ "Yeah but how fast is it? Part 3. OR some thoughts about adiabatic QC". 2006-08-27. Archived from the original on 2006-11-19. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ "Shtetl-Optimized: Thanksgiving Special: D-Wave at MIT". 2007-11-22. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ "In Defence of D-Wave".

- ^ "Quantum computing: In the 'death zone'?". 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

External links

- Official website

- Announcement of the 16-qubit quantum computer demonstration

- IEEE Spectrum: Prototype Commercial Quantum Computer Demo'ed, 13 February 2007

- IEEE Spectrum: Loser: D-Wave Does Not Quantum Compute, January 2010

- Google Tech Talks: Quantum Computing Day 2: Image Recognition with an Adiabatic Quantum Computer

- D-Wave Systems Orion Web Services