Talk:Enigma Variations

| Classical music: Compositions | |||||||

| |||||||

hidden theme

To Hyacinth and others: I think the assertion that "the theme all the variations are based on is never heard. Instead, the piece starts straight away with the first variation" is a little confusing.

Yes, Elgar's enigmatic hidden theme, the one he wrote about, is never heard. However, the piece itself does start with the G minor exposition and, although it's been years since I saw the score, I think it is labeled as the theme. It certainly has that function, and it clearly separate from CAE.

So, if you are distinguishing "the first variation" from "variation 1", it's strictly true, but a little confusing? Does anyone agree this should be reworded, or am I missing some point?

(how does this work - do the contributors get email? I'm new to this thing). --David 01:01, 27 Mar 2004 (UTC)

Enigma theories

I boldly rebalanced the discussion of the enigma - I believe the last edit came across too much as a campaign in favor of one particular theory (the never never theory), dominating the section and unbalancing the entire article. For my own part ISTR Neville Cardus was told the secret before Elgar died, and his reaction made me think it isn't as simple as another "tune". David Brooks 05:24, 18 October 2005 (UTC)

- Fair enough. I'm a firm believer in the "never, never, never" theory, but that doesn't mean it necessarily was what Elgar had in mind (even if the evidence, to me, seems overwhelming). I guess what goes for an article in a music journal, where the author is pushing a particular point of view, does not necessarily go for Wikipedia. What was Cardus's reaction, by the way? (ISTR = I seem to remember?) JackofOz 05:48, 18 October 2005 (UTC)

- I think it would be fair to put a reference to any online discussion of the Van Houten article in the References section (I guess the article itself is not online). The "coincidence" about the drumroll and pennies is just wrong; the idea to use coins came first from Henderson at the first performance, and I think he used sovereigns. On Cardus - I confused him with Newman. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A805303: Elgar said something on his deathbed that the Newman swore he would never repeat, but that it was an unexpected illumination of the Enigma. David Brooks 16:25, 18 October 2005 (UTC)

- Could you illuminate me about the "drumroll and pennies" matter. I've never heard of it. The only "penny" connection I knew about was the one I mentioned in an earlier edit (now deleted), about Dora Penny who, Elgar said, "of all people" should have guessed the enigma. Then the connection was made with the British penny (coin) that had an effigy of Britannia (cf. "Rule, Britannia") on it. JackofOz 23:45, 18 October 2005 (UTC)

- Since you asked... The commonly told story is that the original timpanist, Charles Henderson, pointed out that it is impossible to switch from side drum sticks to naturale without a break, as called for in the score. Henderson had the bright idea of holding a penny in each hand, between two fingers (these are the big pre-decimal pennies, of course). And that this tradition continued ever since. So, even with this version of the story, it wasn't Elgar's idea. Van Houten just put together the words "Penny - Britannia" in an vague, misdirected attempt to justify his theory, but thereby damaged it in my mind.

- Anyway there are several problems with that story. First, according to a first-person account passed on by Jimmy Blades, Henderson used sovereigns, not pennies, because Elgar decided he didn't like the sound of side drum sticks after all, and not specifically because of the performer's problem. This confirms that, at best, Elgar was making a post-hoc connection with Dora's name; coins were not in his initial intention. Also, as it happens, it is playable as written. I can play it perfectly well with a creative grip on two sticks and a mallet, which I find much more manageable than those damned coins! Not all timpanists today use coins (despite this story of Elgar's preferring them); for example the Boston Symphony Orchestra uses a second player with side drum sticks on a spare drum. I've heard that another conductor has asked for a chain to be put on the drum to make it rattle, and MTT (possibly confusing the story) asked an acquaintance of mine to put the coin on the drumhead. David Brooks 00:49, 19 October 2005 (UTC)

- Thanks for that. It all sounds pretty improbable and post-hoc to me too. Unlike the "Rule Brittannia/Never, never/Dora Penny/Britannia" theory which has always resonated strongly with me. Cheers JackofOz 01:25, 19 October 2005 (UTC)

I'm a civilian and I know nothing about classical music, but I find this discussion interesting. What effect does "holding a penny in each hand, between two fingers" have? How does it make it easier to play the piece? Lupine Proletariat 11:57, 3 May 2006 (UTC)

- Elgar asked for a timpani roll played with wooden sticks (invoking the sound of a ship's engines), followed immediately by notes played with normal felt sticks, which many players deem impossible (I disagree). The solution was to hold coins between your fingers and rattle them on the heads, while holding the felt sticks at the ready (I can't) and produce much the same sound (it doesn't). Oh dear, was that a POV? :-) Some claim that Elgar came to prefer the coins anyway. David Brooks 18:00, 11 July 2006 (UTC)

- I recently took part in a performance of this piece. Our timpanist's solution was to place coins on the heads while hitting the heads with felt sticks, so that the coins rattled on their own.Kazuo Ishiguro (talk) 21:56, 9 May 2008 (UTC)

Seventh notes?

Anon 65.247.226.93 wrote "although Elgar's use of accented seventh notes would have been a decidedly nineteenth-century adaptation". Not sure what this means - presumably it's referring to the descending minor seventh intervals, but they don't seem particularly accented to me. Can the anon, or someone else, clarify? There aren't any "seventh notes" (there aren't even any septuplets). David Brooks 18:04, 11 July 2006 (UTC)

I'm betting you're right -- that Anon was referring to the descending sevenths. Elgar himself said these sevenths were important, if memory serves. But they have no accent marks in my Dover facsimile of the Novello orchestral score.Herbivore 02:43, 12 September 2006 (UTC)

The GRS variation

The very brief lines in the main article miss a great deal, I think. The whole Dan-the-bulldog bit only really occurs in the first five measures...what does one say about the rest of the variation? To me, it clearly depicts an organist. Listen to the bass-line statement of the theme: sure, it could be Dan paddling in the river but it also sure sounds like an organist playing the pedals. Then when the brass come in a moment later with the theme again, it sure sounds to me like an organist using the full organ with solo reeds. GRS was also a rather forceful, exuberant personality as I recall. Wspencer11 16:23, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

- I've always had the same reaction. But I've never seen it mentioned in print, so it probably counts as original research :-( David Brooks 17:35, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

- I believe the Ian Parrott book on Elgar mentions this; I wrote a large research paper ages ago on the Variations and the puzzles therein and feel pretty confident I didn't think this up all by myself. Wspencer11 18:06, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

- To be fair, now I've run the variation in my head, I only thought of the last few measures (the brass chorus) as the explicit organ reference. But now I see your point about the pedals. Of course, Elgar was capable of referring to two things at once. David Brooks 18:29, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

- Dan is marked in EE's hand in the MSS, where he barks on emerging from his dip in the Wye, but Sinclair and his energy are certainly there too - some including me hear the Bach organ pedal exercise echoed. --Straw Cat 01:17, 19 February 2007 (UTC)

- To be fair, now I've run the variation in my head, I only thought of the last few measures (the brass chorus) as the explicit organ reference. But now I see your point about the pedals. Of course, Elgar was capable of referring to two things at once. David Brooks 18:29, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

- I believe the Ian Parrott book on Elgar mentions this; I wrote a large research paper ages ago on the Variations and the puzzles therein and feel pretty confident I didn't think this up all by myself. Wspencer11 18:06, 12 July 2006 (UTC)

Genesis of the work

As I recall, Elgar himself told the story of the tiring day of teaching, of how he played the theme "aided by a cigar" (though his word order was a little ambiguous...I have always wondered if the cigar aided his teaching or his playing of the theme [!]), and then improvising sketches of his friends and associates using the theme. If someone can confirm that then I think the current vague non-attribution should be eliminated in favor of a stronger stateement to this effect. Yea/nay? --Wspencer11 (talk to me...) 14:13, 12 September 2006 (UTC)

Yes, I have this citation somewhere & will post it here, assuming I can dig it up.... Herbivore 19:53, 16 September 2006 (UTC)

Mathematical speculation

I dunno, the latest addition to the page seems a bit far-fetched to me. Should it be reverted and discussed here first? --Wspencer11 (talk to me...) 04:16, 30 June 2007 (UTC)

- It's curious and interesting. Problem is, it seems to be the opinion of one or more Wikipedia editors, not that of an independent author whose work we're citing. Thus, it's original research and therefore out of bounds for our articles. It should be removed unless we can find an external reference for it. -- JackofOz 07:07, 30 June 2007 (UTC)

I am relocating my entry regarding the Pi theory to this area as JackofOz suggested. I hope to get it published in a Journal later this year. Since this is a better place for new theories to start, I offer the following Pi theory.

In 2007, a new theory was revealed on public radio's "Performance Today." Elgar dedicated his Enigma Variations to "My Friends Pictured Within." As a "variation" of this, Elgar could have written, "To My Circle of Friends." In mathematics, characteristics of all circles are related by a universal constant, Pi. A common approximation of Pi is 22/7, which equals 3.142857. When the first four numbers of Pi, 3-1-4-2, are played on a musical scale, with 1 being the root, 3 being the third, etc., we hear the opening Theme of his Enigma Variations. Elgar's first four notes are a cipher for Pi.

Sir Edward enjoyed jokes and ciphers, both of which are involved in his "Enigma." The "dark saying" could be a clever reference to the line from the very familiar English nursery rhyme, "Four and twenty BLACKbirds baked in a pie/Pi." Blackbirds are certainly dark, and the pun based on Pi is an unmistakable hint.

Pi could easily be described as "the chief character (who) is never on the stage." This 3-1-4-2 theme is the basis for all of the variations and is heard many times throughout the piece, but Pi itself is hidden.

Sir Edward's clue in 1929 was one more reference to Pi. After referring to the opening crotchets and quavers (eleven quarter notes and eighth notes), Sir Edward advises, "the drop of the seventh in the Theme (bars 3 and 4) should be observed." After the first eleven notes there are two drops of a seventh. In other words, 11 notes x 2/7 = 22/7 = the common approximation of Pi. This clue is not addressed by any previous theory.

Sir Edward, speaking of the Enigma, told Dora Penny in 1899, "It is so well known that it is extraordinary that no one has spotted it." Pi is universally taught as part of primary education and it is "very well known." Many of the previous theories are quite complex.

In two separate letters written to Dora in 1901, Sir Edward used the first four notes of the Enigma Variations as his signature, giving Dora an extra clue. Sir Edward then told Dora, "I thought that you of all people would guess it." These first four notes, the Enigma Theme, are a simple four-character cipher for Pi, the numbers 3-1-4-2. That is why he thought Dora, of all people, would guess it.Dnlsanta 02:47, 1 July 2007 (UTC)

- It's interesting--fascinating, actually--and if you get it published in a peer-reviewed journal we can add it to the proposed theories. I had thought that the "Rule Britannia" theory had been winning out over the others in recent years; I heard a very convincing lecture-demonstration on it on NPR (US) some years ago. Cheers, Antandrus (talk) 03:01, 1 July 2007 (UTC)

- Yes, very fascinating—something the world may have wished it knew 100 years ago? — $PЯINGrαgђ 03:14, 1 July 2007 (UTC)

I know it is trivial, but quite a coincidence that the posting time of the previous entry "is" Pi, 3:14. Maybe Sir Edward is watching us and trying to give us one more clue. Ha Ha. Dnlsanta 00:43, 4 July 2007 (UTC)

- No actually it is my mind control which is slowly taking over the whole musical world. Muahahaha! :P — $PЯINGrαgђ 00:45, 4 July 2007 (UTC)

- It occurs to me that Elgar might be having the last laugh. It's possible that he combined two enigmas in one, and everybody has been searching for a single key all these years when the solution is two-fold. Dnlsanta's theory is the most interesting new one I've heard in a long time, and it bears further discussion out there in the external world of Elgariana (or Enigmiana). Once it gets reported in a reputable publication, then we can include it in our article. Not until then, though. The two-fold proposition, yet to be conclusively proven, is that "Rule Britannia" and the Pi theory both fit all the clues. These include not just the fact that Britannia was on the penny - the shape of which was of course circular - but also that Dora Penny was mathematically inclined. It's a whole gestalt of clues, not just one or the other in isolation. Maybe Elgar is also alluding to the fact that one can try as they might to enumerate all the digits of Pi but will never, never, never get to the end because it's a transcendental number. What an ingenious mind this man must have had. So, if this theory holds water:

- Pi, whose digits never, never, never end, connects to circles

- circles connect to the shape of the penny

- the penny connects to both Britannia and Dora Penny

- Britannia connects to "Rule Britannia"

- "Rule Britannia" brings up "never, never, never" again

- Dora Penny connects to mathematics and, in particular, Pi

- and round and round we go. :)-

- It occurs to me that Elgar might be having the last laugh. It's possible that he combined two enigmas in one, and everybody has been searching for a single key all these years when the solution is two-fold. Dnlsanta's theory is the most interesting new one I've heard in a long time, and it bears further discussion out there in the external world of Elgariana (or Enigmiana). Once it gets reported in a reputable publication, then we can include it in our article. Not until then, though. The two-fold proposition, yet to be conclusively proven, is that "Rule Britannia" and the Pi theory both fit all the clues. These include not just the fact that Britannia was on the penny - the shape of which was of course circular - but also that Dora Penny was mathematically inclined. It's a whole gestalt of clues, not just one or the other in isolation. Maybe Elgar is also alluding to the fact that one can try as they might to enumerate all the digits of Pi but will never, never, never get to the end because it's a transcendental number. What an ingenious mind this man must have had. So, if this theory holds water:

- The only stumbling block I can see is that the number 3.142857 (= 22/7), on which the theory hangs, is only a very rough approximation of Pi; a more exact value is 3.1415926535. So, it's not certain that his reference is to Pi at all, but merely to the fraction 22/7. But that makes it a much less evocative theory, and 22/7 has no intrinsic connection to circles (of friends, or anything else). On the other hand, the actual value of Pi rounded to 3 decimal places is still 3.142.

- On a side note, I once read a theory that Elgar must have been the reincarnation of Robert Schumann, who died less than a year before Elgar was born, and who was also extremely taken by puzzles and ciphers. I rather think this theory will be much harder to prove. But who knows! Are there any Schumann quotes in the Enigma Variations? -- JackofOz 01:38, 4 July 2007 (UTC)

I think that unfortunately, using these sloppy, untestable methods of 'proof', one can 'prove' almost anything. Elgar could have written "Circle of friends" - but he didn't. There are dozens of nursery rhymes and poems which have 'dark' things in them: what is special about blackbirds? What has 'four and twenty' got to do with pi? Has pi really been a universal part of primary school education for the last century?? Every piece of music abounds in numerical values, and with enough mathematical ingenuity these values can be rearranged into almost any form a person wants. The "derivation" of 22/7 is simply numerological mystification. Why exactly should one multiply 11 by 2 and then divide by 7, rather than any other set of operations on these three numbers? The decimal expansion that goes on for ever begins 3.14159, but the rounding is 3.142: you can't have it both ways, at least considering a melody where you have to choose either '1' or '2'. --Tdent (talk) 21:34, 4 February 2008 (UTC)

- Schumann certainly had a very large brain, didn't he? B-) I should listen to my recording of the Variations (with Elgar himself conducting) and see. — $PЯINGrαgђ 04:07, 4 July 2007 (UTC)

How does the "Never, Never" theory relate to Sir Edward's 1929 clue about, "the opening crotchets and quavers" (eleven quarter notes and eighth notes) and "the drop of the seventh in the Theme (bars 3 and 4) should be observed." ?????? 70.238.206.243 12:54, 4 July 2007 (UTC)

The Pi theory seems interesting to me, and I don't understand why we can't post it in the article already. We could just make clear that it is a recent theory that is being submitted for formal review. If you want a reference, you could cite the Performance today interview. It seems on par with the other theories in the article, in that none of them are really proven yet, and most of them don't even have citations themselves. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.205.250.73 (talk) 23:13, 27 December 2007 (UTC)

Current state of the article

Hmm. I am getting less and less happy about all this. The balance of the article has shifted a great deal, so that the music itself has taken a bit of a back seat to presentations of various and sundry attempts to explain the "enigma" of it all. Puzzles are certainly fascinating...but I wonder if it might not be time to consider creating a new article that deals only with that stuff and leaves the music to its own page? "Proof" will never, never, never happen until someone unearths Elgar, his wife, or Jaeger, and applies bamboo splinters under their fingernails until they cough it up. They were the only three who knew the answer. As I understand it, Elgar fully expected people to figure the thing out at first, especially Dora Penny, but when that didn't happen, he gradually let it go and let people turn themselves inside out with explanations, plausible and goofy.

Not only that, but to have one explanation (Bach/Art of Fugue) take up about one-third the total space devoted to all explanations looks so grossly out of balance as to suggest that WP endorses this attempt over all the others. I believe it should be cut way back to bring it in line with the rest of the section. Anyone else feel this way? --Wspencer11 (talk to me...) 14:14, 27 February 2009 (UTC)

- You have a good point there. There are a lot of things that could and should be discussed about the piece itself, for instance, the Ysobel variation has a musical joke for viola players, where they have to skip over string to play the melody, which is a bit of a difficulty for a beginning violist, hint: Isabel (I just can't find the source to cite for that, or even a score for that matter). That's just one example among many, so I would agree that there needs to be more about the music, other than the enigma.

- Splitting off the proposed answers to the enigma into another article sounds like a good idea, if it keeps things at a more manageable size. Although Portnoy in his article makes the Art of Fugue the "definitive" answer, it is not written here in the WP as if it is the "only" solution --- people should be allowed to read and make their own conclusions, and why should the WP offer a definitive judgment of which solution is better when it is not really the purpose of the WP. If the enigmas are split into a different article, the other suggested answers should probably be given a bit more detail as to why people think so.

- Nevertheless, a lot of the ink spilled over the Enigma variations includes the various "answers", so in that case, it is not surprising, since a lot of people will want the answer, or at least some answer. Hence, it isn't surprising that there is a lot of text on the possible answers. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Ll1324 (talk • contribs) 21:24, 27 February 2009 (UTC)

I'm not happy about the statement in the second objection to the Art of Fugue that 'both B natural and B flat can be used in G minor'. The only key apart from D minor that contains B flat, A, C and B natural is C (melodic) minor. As soon as G minor has a B natural, it becomes G major. Although the theme is in G minor, its last note is a B natural - Elgar is using a Picardy third to close the phrase, a device much used by Bach. --Bach&Byte (talk) 08:21, 1 September 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you, I came on this talk page to make that exact point and found that you'd got there first. :) 91.105.7.213 (talk) 00:55, 26 September 2009 (UTC)

Numbering of the Variations

A well-intentioned person recently changed the variation numbering to Arabic, numerals 1 to 14. The full score, by direction of the composer, numbers the variations in Roman, i.e. I to XIV. It should remain that way. P0mbal (talk) 10:48, 12 September 2009 (UTC)

- Agree. Done. -- JackofOz (talk) 11:01, 12 September 2009 (UTC)

- The article had never used Roman numerals before. I checked back two years. What had happened was that an anon had changed 1 to I and 2 to II in separate edits with no reason stated but had left 3 through 14 arabic. A weird mix of roman and arabic remained so I reverted it figuring an anon was just testing the editor. I'm OK with it it being roman as long as all fourteen are that way. Sorry for the confusion.DavidRF (talk) 12:54, 12 September 2009 (UTC)

Recent additions appear to be a copy of http://enigmathemeunmasked.blogspot.com/

Recent additions to this article appear to be largely a copy of an article on this web page. Further, the editor adding the material, Sir Padgett (talk · contribs), appears also to be the author of that article. Not being familiar with the topic, I do know know if this is appropriate. Perhaps someone else can take a look? -- Tom N (tcncv) talk/contrib 01:09, 13 October 2009 (UTC)

- Original research, not to mention a copyright violation. Can't do that. He'd have to publish his ideas in a peer-reviewed publication. I'm taking it all out. Antandrus (talk) 01:18, 13 October 2009 (UTC)

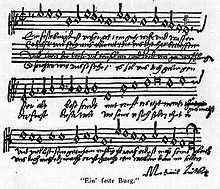

- Ein' feste Burg ... goes with Nimrod? Interesting, fascinating, amazing, etc., and a lot of work done there, but I agree with Antandrus. It unbalances the article too. Consider, is it within scope to have a link to the page instead? I advise user Sir Padgett not to keep putting the article back for reasons stated by Antandrus, and not to be upset by this. Good work Sir P! P0mbal (talk) 18:00, 13 October 2009 (UTC)

- It's great stuff, Sir Padgett. You need to publish this in a peer-reviewed source. I wouldn't object to an external link. But please look at Wikipedia:What_Wikipedia_is_not#Wikipedia_is_not_a_publisher_of_original_thought. For now I have fully protected the page for a brief time, since I'd rather do that than issue a block. Thanks, Antandrus (talk) 00:52, 14 October 2009 (UTC)

Sir Padgett appreciates feedback regarding his discovery at Wikipedia. In response he duly invited numerous peer-reviewed sources to publish his discovery. However, all indicated a standard policy preventing them from publishing an article already featured online. For this reason, Sir Padgett desires in a historic first to share his discovery directly with the digital world at Wikipedia. His paper is featured at http://enigmathemeunmasked.blogspot.com/. He would welcome mention of this historic find by Wikipedia under "Enigma Variations," and Antandrus is invited to provide a brief reference to it under the "Enigma" section. The sound files featured at youtube may also be cited as references at Wikipedia. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Sir Padgett (talk • contribs) 21:41, 25 October 2009 (UTC)

- Do you mean they would not publish it because it is currently available on your blog? I did read it, and found it fascinating (please do note, I have a skeptical streak, as a former academic). Did any of the publishers indicate they would consider publishing it if your took it down?

- For Wikipedia purposes, we can't use blogs per our reliable source policy; sorry, I can't do anything about that, as community consensus determines policy here; the few exceptions don't apply in this case (e.g. you can use a blog as a source on the article on that blog for claims it makes about itself). I have no objection to putting "unmasked" in as an external link, and submit that idea to others reading this thread. Good work -- really. Antandrus (talk) 00:26, 26 October 2009 (UTC)

- Sorry, but I'm skeptical. Mr. Padgett has already been in contact with Prof. Julian Rushton and if he didn't buy the idea, then why should we? I found the blog post to be too much of a sales pitch rather than an academic paper... which tend to be more level-headed. The sound samples all contained an extremely piercing instrument (flute/trumpet) playing Mighty Fortress over barely recognizable Elgar on a background organ. I feel the author is clearly trying to "sell" his idea here. If its a good idea, it will make it into print eventually... but that shouldn't be our call. My two cents.DavidRF (talk) 00:54, 26 October 2009 (UTC)

- On reading it, my feeling was that the blog is very well argued, and Sir Padgett's three rules make a lot of sense. But for me the argument falls down within five seconds of starting to listen to it. I am hugely sceptical - playing Ein feste Burg in a sort of desultory mixed minor mode over the Enigma theme just doesn't convince me at all. To me it sounds unmusical, which Elgar never was, and - worse - unElgarian and unEdwardian. In fact, it makes the work sound "very 21st century". After having heard it, and reading the blog again, the whole argument seemed egregiously Procrustean. Personally, I felt patronised by statements such as "For those with eyes that see and ears that hear, there can no longer be any doubt about the solution to Elgar's 110 year old enigma." If the research garners support among professional musicologists then it certainly should be reported in the Wikipedia article, but until then it's just original research. I don't think there should even be a link to it until it has at least been discussed in mainstream musicology articles. --RobertG ♬ talk 07:25, 26 October 2009 (UTC)

Dr. Julian Rushton staunchly rejects the notion there could be any melodic solution to Elgar’s Enigma Theme, so obviously any proposed melody will meet with a fatal skepticism on his part regardless of its merits. He not only stubbornly maintains this position, but does so in direct contraction with the composer's own published comments on this subject. If that is the measure of a respected “musicologist,” then I consider myself fortunate not be counted among such an obtuse coterie. Rushton’s rush to judgment on this matter will most assuredly be relegated to the ash heap of history where time and more sober minds will surely jettison it. After all, musicologists are not infallible—I’ve met enough in my time to know better.

The purpose for contrasting instrumentation in the sound files is to aid the listener in distinguishing between Ein’ feste Burg, the Enigma Theme and Variation IX. Of course anyone familiar with the history of Ein’ feste Burg would appreciate the choice of flute for the hidden melody. As computer sound systems vary widely in quality, sheet music is provided for each sound sample to permit listeners the opportunity to study the solution in greater depth. These sound files were generated on Finale 2009 using Garriton sounds, recognized as being among of the best in the industry. I wonder if DavidRF even studied the sheet music, or did this material elude him because he does not know how to read music?

As for RobertG’s comments regarding Elgar’s deliberate cycling between the minor and major modes, I encourage him to listen to the sound file of Ein’ feste Burg played through and over Nimrod (Variation IX) where the composer does not engage in this device. After hearing it, the answer should be abundantly clear, one that only a bumbling musicologist could overlook completely. There’s a reason why the solution has gone unfound for 110 years, and “authorities” like Rushton are to blame. By the way, the solution is already in print...online. (206.174.239.59 (talk) 01:28, 27 October 2009 (UTC))

- Complete Variation Nimrod featured on organ with Ein' feste Burg played "through and over" it on trumpet as a counterpoint.

- Elgar’s Enigma Theme Unmasked This is the formal paper documenting Robert W. Padgett’s novel solution “Ein’ feste Burg” as the missing theme to Elgar’s Enigma Variations.

- Wow. Mr. Padgett is a sweet-talker. Luckily for him, my opinion doesn't matter. That's the whole point here. We are not a primary source. Publish this somewhere else. Also, please try to remember that anyone takes the time to read your blog and give you feedback is doing you a favor. I think it would also help to do some homework and cite previous work that's been in this area. By previous work, I mean articles in the type of journals you hope to publish in, not just books and blogs. Also, try to include more than one theme in your analysis. You run "Ein' feste Burg" through all sorts of analyses, but we have no "control group" for those comparisons. Finally, in my opinion you should cut down on the arrogant tone. It implies that you are covering up weaknesses in your arguments and you don't want to make that implication. If your arguments are sound, you won't need to do that. Best of luck. Cheers.DavidRF (talk) 01:58, 27 October 2009 (UTC)

DavidRF is correct in stating his opinion is irrelevant. As for competing themes, many have been proposed and studied elsewhere, but none satisfy. The purpose of my article is not to show why those themes are incorrect, but rather why "Ein' feste Burg" is the proper solution. DavidRF’s suggestion to include a “control group” of competing themes is akin to instructing a mathematician to run through a list of incorrect answers to a problem to show why the solution is correct. Such an approach may sound scientific, but it’s wholly unmathematical and unmusical. In suggesting Mr. Padgett sounds like a "sweet-talker," DavidRF strongly implies weaknesses in his own arguments, not to mention a decidedly arrogant tone. "Ein' feste Burg" is the missing melody, and Wikipedia may choose to post the truth or not. Eventually it will--mark my words. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.173.66.10 (talk) 21:23, 27 October 2009 (UTC)

- I thought my response was fairly restrained considering you baselessly accused me of not being able to read music in your previous post. I even made some good-natured suggestions. You certainly are correct in that my opinion does not matter!!! I'm just a volunteer hiding behind a pseudonym sifting through information from reliable sources. Your theories are not published in a reliable source, they are original research. Whether or not you are correct is not the point here. Best of luck to you.DavidRF (talk) 21:45, 27 October 2009 (UTC)

- I would be greatly surprised if an English Catholic composer at the turn of the 20th century would "hide" the most famous hymn of German Lutheranism in one of his most lyrical works. That the British Royal Family, with its German roots, might be fond of the hymn is one thing, but I doubt if it would have had pleasant associations for Elgar himself. Janko (talk) 23:07, 29 November 2009 (UTC)

- It would be very shocking indeed if Elgar, an English Catholic, based his Enigma Variations on the most famous Lutheran hymn in history. Yet just before he composed the Enigma Variations, Elgar was sketching a symphony in honor of General Gordon, the British commander slaughtered at the Siege of Khartoum. General Gordon was Anglican. -- Sir Padgett —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.183.171.190 (talk) 23:36, 22 December 2009 (UTC)

82.173.128.227's edits

As he tried to do at the Dutch version of Wikipedia, the person called 82.173.128.227 tried (Revisions 9 January 2010) to "prove" the superiority of his own theory above Westgeest's solution published in 2007

- - by deleting useful and concise information in the article about Westgeest's theory

- - by adding to it value judgements as 'far-fetched' and words of that kind

- - by adding qualifications as 'most plausible' to his own theory

- - by trying to add a counter-argument

- - by removing the reference to Westgeest's book, which was published in 2007.

I restored those passages.--Esgroot (talk) 14:25, 12 January 2010 (UTC)

WHO CAN STOP THIS MAN?

Again this person, now called 82.118.116.119, tries to start a dispute in this article (Revisions 9 February 2010) in order to "prove" that his own theory is right by adding a (wrong) argument in the passage about Westgeest's theory which has been published in 2007. I restored the passage.81.205.147.164 (talk) 10:59, 10 February 2010 (UTC)

Please do NOT take discussion into this article

As at the above number 10 and 11, someone is trying to start a discussion (22 March) by adding a (wrong!) argument in the passage about Westgeest's theory which has been published in 2007. I restored the passage. Please reread the book and send an email to the author: I'm sure Westgeest will be glad to discuss it with you! —Preceding unsigned comment added by 81.205.147.164 (talk) 19:35, 22 March 2010 (UTC)

AGAIN AND AGAIN: 82.173.128.227's edits. WHO CAN STOP HIM?

As he tried to do at the Dutch version (Revisions 11 January 2010) and several times in the English version of Wikipedia (Revisions 9 January 2010, 9 January 2010, 9 February 2010 and 22 March) the person called 82.173.128.227 now tries again (Revisions 24 March 2010) to "prove" the superiority of his own theory above Westgeest's solution published in 2007

- - by deleting and changing useful and concise information in the article about Westgeest's theory

- - by adding to it (wrong!) remarks

- - by removing the reference to Westgeest's book, which was published in 2007.

I restored the passage. Again I say this: please reread Westgeest's book and send an email to the author: I'm sure Westgeest will be glad to discuss it with you!81.205.147.164 (talk) 20:54, 24 March 2010 (UTC)

AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN: 82.173.128.227's edits. WHO CAN STOP HIM?

As he tried to do at the Dutch version (Revisions 11 January 2010) and several times in the English version of Wikipedia (Revisions 9 January 2010, 9 February 2010, 22 March 2010 and 24 March 2010) the person called 82.173.128.227 now tries again (Revisions 31 March 2010) to "prove" the superiority of his own theory above Westgeest's solution published in 2007

- - by deleting and changing useful and concise information in the article about Westgeest's theory

- - by adding to it (wrong!) remarks

- - by removing the reference to Westgeest's book, which was published in 2007.

I restored the passage and added again the reference to Westgeest's book. Again I say this: please reread Westgeest's book and send an email to the author: I'm sure Westgeest will be glad to discuss it with you!81.205.147.164 (talk) 18:27, 31 March 2010 (UTC)

Eusebius, please read this

17:23, 1 April 2010 you removed from the article the passage about the Westgeest's Pathetique-theory and wrote: 'removing the "Pathétique" Reference as WP:OR from a WP:SPA with WP:COI - self published works do not satisfy the standard of WP:RS. DO NOT RESTORE until better sourcing is found'.

Eusebeus, I am sorry to say, but you are wrong in this. The Pathetique-theory is not 'original resource'. It was published in 2007. See the reference in the article:

- Westgeest, Hans (2007). Elgar's Enigma Variations. The Solution. Leidschendam-Voorburg: Corbulo Press. ISBN 978-90-79291-01-4 (hardcover), ISBN 978-90-79291-03-8 (paperback).

'Single purpose account'? The only thing I did, and what I was forced to do, was restoring a passage which one particular person, called 82.173.128.227, apparently doesn't like to be there and which he deleted several times in order to defend Van Houten's Rule Brittannia-theory from 1976. He even removed the reference to Westgeest's book! Is that providing neutral information??? And fair play?

'Conflict of interest'? As you know, a Wikipedia conflict of interest (COI) is an incompatibility between the aim of Wikipedia, which is to produce a neutral, reliably sourced encyclopedia, and the aims of an individual editor. I only tried to keep the passage about Westgeest's Pathetique-theory in the article, where it belongs. It is a concise and neutral account of an important theory which was published in a book in 2007.

Please look at what the person called 82.173.128.227 did to the Pathetique-theory (and to his own theory) in: Revisions 9 January 2010, 9 February 2010, 22 March 2010 and 24 March 2010 And in the Dutch Wikipedia art. 'Enigma Variaties': Revisions 11 January 2010 Now that's what I call a COI !

Please restore the passage.81.205.147.164 (talk) 19:51, 1 April 2010 (UTC)

The Pi Solution to Elgar's Enigma

"Solving Elgar's Enigma", co-written by C R Santa and Matthew Santa, is now printed in Current Musicology, a journal published by Columbia University.

I think the following would be an appropriate addition to the Enigma section of Elgar. Does anyone object?

The Pi Solution as confirmed by Elgar's 1929 notes

In 2007, a retired engineer observed that the first four notes were scale degree 3-1-4-2, decimal Pi. Pi is a constant in all circles (circumference divided by diameter.) It is usually approximated by 3.142 as a decimal or 22/7 as a fraction. Further research uncovered that fractional Pi can be found within the first four bars by observing that two “drops of a seventh” follow exactly after the first eleven notes, giving us 11 x 2/7 = 22/7. Elgar included a “dark saying” into his first six bars by using “Four and twenty blackbirds (dark) baked in a pie (Pi).” The first four and twenty black notes each have “wings” (ties or slurs,) and Elgar indicated that the enigma was contained only in the first six bars bar using a double bar after the sixth bar. The double bar usually indicates the end of a piece but Elgar inserted it before the end of the first phrase.

Pi fits all the clues given by Elgar in 1899. Viewing “theme” as the central idea/concept explains how Pi can be the “larger theme which 'goes', but is not played.” Pi “is never on the stage.” The 'dark saying' which must be left unguessed, turns out to be a pun from a familiar nursery rhyme.

As if to confirm Pi, Elgar wrote three sentences in 1929, each containing a Pi hint. Elgar was 72 old and no one had guessed the enigma after 30 years. In his first sentence he referred to two quavers and two crotchets (hint at 22) and then in the third, he referred to bar 7 (hint at /7.) Putting them together yields another 22/7. In his second sentence he wrote, “The drop of a seventh in the Theme (bars 3 and 4) should be observed,” which leads us to find fractional Pi, 22/7, in the first four bars. Elgar said the solution was “well known.” Pi is taught to school children as part of a basic education.

Elgar wrote his Enigma Variations in the year following the very foolish Indiana Pi Bill of 1897 which attempted to legislate the value of Pi. Years later in 1910, Elgar wrote “the work was begun in a spirit of humour.” Elgar enjoyed such japes, as well as codes, puzzles and nursery rhymes. No other proposed “solution” has offered any relevance to Elgar’s 1929 hints including his “drop of a seventh in the 3rd and 4th bar.”

Dnlsanta (talk) 18:51, 17 September 2010 (UTC)

- I was considering adding that information myself, but was having trouble finding suitable sources. The paragraph you have provided may need some rewriting to account for the dissidents of this theory, but I do believe the pi solution merits a section. Thanks for bringing this up. Cheers. sonia♫ 19:30, 17 September 2010 (UTC)

- Agreed. Very impressive work! We can copyedit it for wiki style and as Sonia suggests. Antandrus (talk) 15:46, 20 September 2010 (UTC)

Santa's research is insightful and worth mentioning. - Sir Padgett —Preceding unsigned comment added by 99.186.214.159 (talk) 16:32, 17 October 2010 (UTC)

- Added, in brief to avoid undue weight. Open to tweaking :) sonia♫ 03:29, 22 December 2010 (UTC)

The Pathétique-theory

21 July Theodore James added some remarks criticizing Westgeest's Pathétique-theory. I think we'd better start the discussion here on this talk page.

- “The connection between Variation IX [and Beethoven] was out in the open during Elgar’s lifetime”. Indeed it was. Elgar himself disclosed it (see Westgeest 2007, p. 47-48) and related to Dora Penny (p. 46-47) that the beginning of Nimrod refers to Beethoven. He called it “only a hint, not a quotation”. What that hint is and how it works, wasn’t totally clear untill Westgeest’s theory was published in 2007.

- “In any case the connection concerns a variation, not the original theme headed 'Enigma'.” Right! As Westgeest writes, ‘the original theme’, the one which is “ a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard”, is not the melody at the beginning of the work headed ‘Enigma’. (That is only the minor version). It consists of the first nine notes of Nimrod, which is, as Westgeest assumes, the first piece of the Variations Elgar composed. Elgar composed it as a countermelody to the - larger, wellknown - theme of the 2nd movement of Beethoven’s Pathétique. What Elgar meant by all this you can read in Westgeest’s book p. 49-58.