History of the College of William & Mary

The history of The College of William & Mary can be traced back to a 1693 royal charter establishing "a perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and the good arts and sciences" in the British Colony of Virginia. It was named for the reigning joint monarchs of Great Britain, King William III and Queen Mary II. The selection of the new college's location on high ground at the center ridge of the Virginia Peninsula at the tiny community of Middle Plantation is credited to its first President, Reverend Dr. James Blair, who was also the Commissary of the Bishop of London in Virginia. A few years later, the favorable location and resources of the new school helped Dr. Blair and a committee of 5 students influence the House of Burgesses and Governor Francis Nicholson to move the capital there from Jamestown. The following year, 1699, the town was renamed Williamsburg.

During the American Revolution about 75 years later, the college successfully made the transition from British support and a role in government and the established church under Bishop James Madison, and added post graduate programs including the School of Law under George Wythe to become a "university" (although the traditional name using the word "college" has always been retained). With buildings and finances both devastated by the American Civil War (1861–1865), through the perseverance of school presidents Benjamin Stoddard Ewell and Lyon Gardiner Tyler, funding from the U.S. Congress and the Commonwealth of Virginia eventually restored the infrastructure and facilitated expansion of the school's programs with a new emphasis on educating teachers for the state's new public school divisions.

In 1918, William and Mary became the first of Virginia's state-supported colleges and universities to admit women as well as men to its under graduate programs. Adjacent to the restored colonial capital area which became Colonial Williamsburg beginning in 1926, the school has long been involved in the programs and work there. A few blocks away from the campus in the Historic Area, many students continue to attend Bruton Parish Church, a tradition of over 300 years duration.

Prologue

When the first permanent settlement in the British Colony of Virginia was established at Jamestown beginning in 1607, the role of the Church of England and its relationship to the government had been established by King Henry VIII some years earlier. The same relationship was established in the new colony.

Religious leaders in England felt they had a duty as missionaries to bring Christianity (or more specifically, the religious practices and beliefs of the Church of England), to the Native Americans in the new colony. There was an assumption that what were viewed by the English to be mistaken spiritual beliefs of the natives, which differed from their own, were largely the result of a lack of education and literacy. This was primarily because it was noted that the Powhatan people who lived in the area, which they called "Tsenacommacah," did not have a written language. Therefore, teaching them these skills would logically result in what the English saw as enlightenment in Native religious practices, and bring them into the fold of the church.

A school of higher education for both Native American young men and the sons of the colonists was one of the earliest goals of the leaders of the Virginia Colony.[1] Within the first decade, a promising start of a "University" was initiated as part of the progressive colonial outpost of Henricus under the leadership of Sir Thomas Dale. However, the Indian Massacre of 1622 destroyed the Henricus development, postponing the colonists' hopes for a school of higher education. It would be almost 70 more years before their efforts to establish a school of higher education would be successfully renewed.

Founding

In 1691, the House of Burgesses sent Reverend Dr. James Blair, the colony's top religious leader and rector of Henrico Parish at Varina, to England to secure a charter to again establish a school of higher education. Some scholars believe Blair utilized some of the original plans from the elaborate but ill-fated earlier attempt at Henricus.

Reverend Blair, who was the Commissary of the Bishop of London in the colony, journeyed to London and began a vigorous campaign. Control of the Native Americans of the Powhatan Confederacy was no longer a priority in the Colony, as they had been largely decimated and reduced to reservations after the last major conflict in 1644. However, the religious principle of educating them and other Native Americans in Christianity was nevertheless retained as a vital part of the school's planned mission, perhaps as a moral (and therefore also political) incentive to help successfully gain support and approval in London. With support from his friends, Henry Compton, the current Bishop of London, and John Tillotson (Archbishop of Canterbury), Blair was ultimately successful.[2]

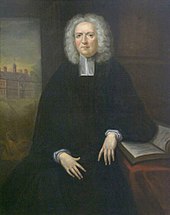

The College was founded on February 8, 1693, under a royal charter (technically, by letters patent) secured by Blair to "make, found and establish a certain Place of Universal Study, a perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and the good arts and sciences...to be supported and maintained, in all time coming."[3] Named in honor of the reigning monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II, the College was one of the original Colonial colleges. The Charter named Blair as the College's first president (a lifetime appointment which he held until his death in 1743). The new school was also granted a coat of arms from the College of Arms.[4]

William & Mary was founded as an Anglican institution; governors were required to be members of the Church of England, and professors were required to declare adherence to the Thirty-Nine Articles.[5]

The charter called for a center of higher education consisting of three schools: the Grammar School, the Philosophy School and the Divinity School. The Philosophy School instructed students in the advanced study of moral philosophy (logic, rhetoric, ethics) as well as natural philosophy (physics, metaphysics, and mathematics); upon completion of this coursework, the Divinity School prepared these young men for ordination into the Church of England.

This early curriculum, a precursor to the present-day liberal arts program, made William & Mary the first American college with a full faculty. The College has achieved many other notable academic firsts. Although most other planned goals were met or exceeded, the efforts to educate and convert the natives to Christianity were to prove less than successful once the College was established.

Colonial history

In 1693, the College was given a seat in the House of Burgesses and it was determined that the College would be supported by tobacco taxes and export duties on furs and animal skins. In 1694, when Blair returned from England, as the past Rector of Henrico Parish (then along the western frontier of the colony), he was very aware of the fate of Henricus and the first attempt at a college there, both of which had been annihilated in the Indian Massacre of 1622.

The peaceful situation with the Native Americans in the Virginia Peninsula area by that time, as well as the central location in the developed portion of the colony located only about 8 miles (13 km) from Jamestown, but on high ground midway between the James and York Rivers, must have appealed to the College's first president, for he is credited with selecting a site for the new college on the western outskirts of the tiny community of Middle Plantation in James City County. Blair and the trustees of the College of William and Mary bought a parcel of 330 acres (1.3 km2) from Thomas Ballard, the proprietor of Rich Neck Plantation, for the new school,[6] just a short distance from the almost new brick Bruton Parish Church, a focal point of the extant community, and not far from the headwaters of Archer's Hope Creek, later renamed College Creek.

In 1694, the new school opened in temporary buildings. Properly called the "College Building," the first version of the Wren Building was built at Middle Plantation beginning on August 8, 1695 and occupied by 1700 on a picturesque site. The present-day College still stands upon those grounds, adjacent to and just west of the restored historic area known in modern times as Colonial Williamsburg.

After the statehouse at Jamestown burned in 1698, the legislature moved temporarily to Middle Plantation, as it had in the past. Upon suggestion of students of the College, the capital was permanently relocated there, and Middle Plantation was renamed Williamsburg in 1699. Following its designation as the Capital of the Colony, immediate provision was made for construction of a capitol building and for platting the new city according to the survey of Theodorick Bland. Both the extant Bruton Parish Church and the College Building held prominent locations in the new plan, with the Wren Building site aligned at the center of the western end of the new major central roadway, Duke of Gloucester Street, itself laid along a pathway running along the midpoint ridge of the Peninsula and long a dividing line between two of the original eight shires of Virginia, York and James City Counties. At the other (eastern) end of the Duke of Gloucester Street, opposite the College Building, the new Capitol was built.

Williamsburg, which was granted a royal charter as a city in 1722, served as the capital of Colonial Virginia from 1699 to 1780. During this time, the College served as a law center and lawmakers frequently used its buildings. It educated future U.S. Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Tyler. The College issued George Washington his surveyor's certificate, which led to his first public office.[7] Washington was later appointed the first American Chancellor in 1788 following the American Revolution. Serving as Chancellor of the College was to be his last public office, one he held until his death in 1799.

George Wythe, widely regarded as a pioneer in American legal education, attended the College as a young man, but dropped out unable to afford the fees. Wythe went on to become one of the more distinguished jurists of his time. Jefferson, who later referred to Wythe as "my second father," studied under Wythe from 1762 to 1767. By 1779, Wythe held the nation's first Law Professorship at the College. Wythe's other students included Henry Clay, James Monroe and John Marshall.[8]

The College also educated three U.S. Supreme Court Justices (John Marshall, Philip Pendleton Barbour and Bushrod Washington) as well as several important members of government including Peyton Randolph and Henry Clay.

Separation from England

During the period of the American Revolution, Freedom of Religion and the Separation of Church and State were each established in Virginia beginning in 1776. The English government and the Church of England each lost prominence and control. While they desired independent government, leaders and citizens of the new state and country did not reject their church, only its structure in relationship to government. Worship continued, in some places at a heightened pace, during the difficult years of the War and thereafter. Although shorn of a governmental role and financial support, the Church survived in modified form as what is now known as The Episcopal Church (United States). Before the Revolution, there had been no bishop in the colony. After the War, the first Episcopal Bishop of Virginia was the Right Reverend James Madison (1749–1812). He was a cousin of future President of the United States James Madison, and was ordained in England just before the American Revolution.

Future U.S. President James Madison was a key figure in the transition to religious freedom in Virginia, and Reverend Madison, his cousin and Thomas Jefferson, who was on the Board of Visitors, helped The College of William & Mary to make the transition as well, and to become a university with the establishment of the graduate schools in law and medicine in the process.

A 1771 graduate of the College, and an ordained minister in the Church of England, Reverend James Madison was a teacher at William & Mary as the hostilities of the American Revolution broke out, and he organized his students into a local militia. During 1777, he served as chaplain of the Virginia House of Delegates. The same year, Loyalist sympathies of the College President, Reverend John Camm (who had been the initial litigant in the Parson's Cause case 1758-1764), brought about his removal from the faculty. Reverend Madison became the 8th president of The College of William & Mary in October, 1777, the first after separation from England.[9]

As its President, Reverend Madison worked with the new leaders of Virginia, most notably Jefferson, on a reorganization and changes for the College which included the abolition of the Divinity School and the Indian School, which was also known as the Brafferton School. The 1693 royal charter provided that Indian School of the College educate American Indian youth. College founder James Blair had arranged financing for that purpose using income from Brafferton Manor in Yorkshire, England, which had passed to the estate of scientist Robert Boyle. The Indian School, intended to "civilize" Indian youth, was begun in 1700. However, Native American parents resisted enrolling and boarding their children, and many of those who enrolled were captive children from enemy tribes, including the first six students. Enrollment was never strong, revived somewhat after construction of the fine brick Brafferton School building in 1723. The school was never very successfully in achieving any quantity of Indian conversions to Christianity, but did help educate several generations of interpretors who could aid in communication. The school's dedicated income from England was interrupted by the Revolutionary War. By 1779, the Brafferton School had permanently closed, although "The Brafferton", as it is known in modern times, remains a landmark building on the campus.[10]

In June 1781, as British troops moved down the Peninsula, Lord Cornwallis made the president's house his headquarters, and the institution was closed for a few months of that year, which saw the surrender at Yorktown on October 19.

Antebellum era 1776–1861

The colonies declared their independence in 1776 and the College of William & Mary severed formal ties to England. However, the College's connection to British history remains as a distinct point of pride; it maintains a relationship with the British monarchy and includes former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher among those who have served as Chancellors. Queen Elizabeth II has visited the College twice.[11]

In 1842, alumni of the College formed the Society of the Alumni[12] which is now the sixth oldest alumni organization in the United States. In 1859, a great fire caused destruction to the College. The Alumni House is one of only several original antebellum structures remaining on campus; notable others include the Wren Building, the President's House, and the Brafferton.

Civil War, Reconstruction, becoming a state institution

At the outset of the American Civil War (1861–1865), enlistments in the Confederate Army depleted the student body and on May 10, 1861, the faculty voted to close the College for the duration of the conflict. The College Building was used as a Confederate barracks and later as a hospital, first by Confederate, and later Union forces. The Battle of Williamsburg was fought nearby during the Peninsula Campaign on May 5, 1862, and the city fell to the Union the next day. The Brafferton building of the College was used for a time as quarters for the commanding officer of the Union garrison occupying the town. On September 9, 1862, drunken soldiers of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry set fire to the College Building,[13] purportedly in an attempt to prevent Confederate snipers from using it for cover. Much damage was done to the community during the Union occupation, which lasted until September 1865.

Following restoration of the Union, Virginia was destitute from the War. The College's 16th president, Benjamin Stoddert Ewell finally reopened the school in 1869 using his personal funds. He later sought war reparations from the U.S. Congress, but he was repeatedly put off. Ewell's request was finally honored, and Federal funds were appropriated, but not until 1893. Meanwhile, after some years of struggling, the College closed in 1882 due to lack of funds.

It has become legendary that, every single morning of that long seven-year period, President Ewell would arise and ring the bell calling students to class, so it could never be said that William and Mary had abandoned its mission to educate the young men of Virginia.[14]

In 1888, William & Mary resumed operations under a substitute charter when the Commonwealth of Virginia passed an act[15] appropriating $10,000 to support the College as a state teacher-training institution. Dr. Ewell, who had grown quite old and spent much of his private financial resources to keep the College alive, was finally able to retire, with the future of his beloved College on a new and more stable course again. He was no doubt honored and satisfied that former U.S. President John Tyler's son would be taking the reins.

20th century: coeducational and teacher training programs

Lyon Gardiner Tyler (1853–1935) became the 17th president of the College following President Ewell's retirement. Tyler began expanding the College into a modern institution. He assembled a faculty known affectionately as the "Seven Wise Men," himself holding the chair of history. In March 1906 the General Assembly passed an act taking over the grounds of the colonial institution, and it has remained publicly-supported ever since.

In 1918, William & Mary was one of the first universities in Virginia to become coeducational with its admission of women. During this time, enrollment increased from 104 students in 1889 to 1269 students by 1932. Tyler retired in 1919 as president.

Lyon Tyler was succeeded by the College's 18th president, J.A.C. Chandler, who continued and greatly expanded the initiatives of that began under Dr. Tyler. Also a historian and author, Dr. Chandler had spent his career prior to coming to William and Mary in Education, and had developed an acclaimed "Model Schools" program at Richmond City Public Schools during the ten years he served there as Superintendent of Schools.

Dr. Chandler was both innovative and energetic. As he continued programs of modernization and coeducation begun under Tyler, he had access to Tyler, who was still living nearby at his home in Charles City County. (Ironically, Dr. Tyler outlived Chandler by a year).

He also can be credited with the recruitment of Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, who was comfortably serving a wealthy church in Rochester, New York, but as Dr. Chandler knew, still had strong ties and dreams for Williamsburg. Beginning ostensibly at William and Mary as an instructor and fund-raiser, Dr. Goodwin was soon pursuing historical restoration ideas and the funding for them in addition to raising funds for the school's programs in general.

The dedication of William and Mary's new Phi Beta Kappa Hall in 1926 gave Dr. Goodwin the opportunity to spend time with industrialist and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller as they visited Williamsburg with three of their children. Dr. Goodwin, who was also rector of Bruton Parish Church, shared his dreams and visions of restoring as much as possible of the birthplace of America's democracy. While his father had been the hard-driving businessman who generated a lot of animosity around the country as he was the "front man" for Standard Oil, his only son, John Jr., was a much more shy and reserved individual whose job it became to be a philanthropist with his wife in handling the family's great wealth. Dr. Goodwin was successful, possibly beyond the wildest dreams of he or Dr. Chandler, in getting John and Abby to become part of the dream that ended up becoming Colonial Williamsburg (CW).

Although most of the Restoration eventually came under a foundation separate from the College, the ties between the College and CW remain close. Among what was accomplished on the campus itself of great benefit to the College are were notably the restorations/reconstructions of the Sir Christopher Wren Building, the President's House and the Brafferton (the President's office) between 1928 and 1932.

Dr. Chandler had many activities going on in the 1920s other than the Restoration, which became increasingly Dr. Goodwin's principal focus. As a former public school leader, Dr. Chandler knew firsthand of the urgent need in the state for additional efforts to educate teachers and other professionals for the public schools throughout the state.

Despite facing the challenges presented by the Great Depression and his own failing health as the College entered the 1930s, Chandler's greatest legacy at William and Mary is considered by many to be School of Education, which began a long continuing tradition of providing an education to many of Virginia's public school teachers. Although he had left local service many years earlier there, it is symbolic that Richmond Public Schools named a new school after Dr. Chandler shortly after his death, the only former W&M President accorded such an honor in the capital city.

During his 14-year tenure, under Dr. Chandler, the College's full-time faculty grew to over 100 and the student body grew from 300 to over 1200 students, despite the Depression. Affordable and accessible education was also a hallmark of Chandler's tenure. In 1930, William & Mary expanded its territorial range by establishing a branch in Norfolk, Virginia. This extension would eventually become the independent state-supported institution known as Old Dominion University. Other branches around the state were to follow. Partially as a result, when competition for state higher education funding, the College has enjoyed an especially supportive relationship with the Virginia General Assembly, which partially funds the various local programs for K-12 public school education throughout the state. The School of Education has continued and expanded that commitment by conducting in-service training and summer programs which enable continuing education of teachers and other instructional personnel. As a result, many of Virginia public school teachers who utilize these services later achieve masters and doctoral degrees, and sometimes advance to positions of leadership in school divisions or with the State Department of Education.

Mid 1930s through WW II

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2008) |

William and Mary's budding "Air School" begun under Dr. Chandler. The College had two different facilities during its short venture into aviation. Both were located originally along what is now VA-Route 603 (Mooretown Road). The newer facility changed to private operation and was the namesake for modern-day Airport Road in York County.[16] The program was a casualty of a combination of the economic environment of the Depression, Dr. Chandler's failing health, and more than any other factor, most likely the changes in a growing technology which quickly shifted to the military and commercial sector.[17]

Significant campus construction continued under the College's nineteenth president, John Stewart Bryan. Son of Joseph Bryan, a prominent Richmonder, John Stewart was a newspaperman and businessman. As Virginia recovered from the Depression, in 1935, the Sunken Gardens were constructed, just west of the Wren Building. The sunken design is taken from a similar landscape feature at Chelsea Hospital in London, designed by Sir Christopher Wren.

Post WW-II through modern times

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2010) |

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh visited the College on October 16, 1957, where the Queen spoke to the College community from the balcony of the Wren Building. The Queen again visited the College on May 4, 2007 as part of her state visit for the 400th anniversary of the establishment of the settlement at Jamestown.

In 1974, Jay Winston Johns willed Ash Lawn-Highland, the 535-acre (2.17 km2) historic Albemarle County, Virginia estate of alumnus and U.S. President James Monroe, to the College. The College restored this historic Presidential home near Charlottesville and opened it to the public.[18]

Sir Christopher Wren Building

The building officially referred to as the "Sir Christopher Wren Building" was so named upon its renovation in 1931 to honor the English architect Sir Christopher Wren. The basis for the 1930s name is a 1724 history in which Hugh Jones stated that the 1699 design was "first modelled by Sir Christopher Wren" and then was adapted "by the Gentlemen there" in Virginia; little is known about how it looked, since it burned within a few years of its completion. Today's Wren Building is based on the design of its 1716 replacement. The College's Alumni Association recently published an article suggesting that Wren's connection to the 1931 building is a viable subject of investigation.[19] A follow-up letter clarified the apocryphal nature of the Wren connection.[citation needed]

In the early 20th century, the Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller Jr. undertook a massive reconstruction and restoration project in Williamsburg—the project culminated in Colonial Williamsburg. The Wren Building was the first major building to be reconstructed or restored as part of the project. Following a drawing on the Bodleian copper plate (ca. 1740) and plans Thomas Jefferson drew of the interior in 1772, the Boston architectural firm of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn rebuilt the building to its second form (1715–1859). The architectural firm subsequently designed complete reconstructions of the Capitol and the Governor's Palace, the original versions of which had burned during the eighteenth century.[20]

Two other buildings around the Wren Building complete a triangle known as "Ancient Campus": the Brafferton (built in 1723 and originally housing the Indian School, now the President and Provost's offices) and the President's House (built in 1732).

The Wren Building is sometimes described as the oldest educational building in continuous use in the United States, although it ceased to serve its original function several times over the centuries. The Wren Building was known in colonial times as "The College" because, in the early years of the institution, the entire College of William & Mary consisted solely of the Wren Building. Inside its hallowed walls, all students (males only at that time) lived, ate, studied, worshiped and learned.

Firsts

William & Mary is the second-oldest institution of higher learning in the United States, established in 1693 (Harvard is the oldest).

The College was the first to teach Political Economy; Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations was a required textbook.[citation needed] In the reform of 1779, William & Mary became the first college in America to become a university,[21] establishing faculties of law and medicine; it was also the first college to establish a chair of modern languages. Chemistry was taught beginning in the nineteenth century; alumnus and future Massachusetts Institute of Technology founder William Barton Rogers served as the College's Professor of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry from 1828–1835.

Beginning with his 1778 Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, alumnus and future University of Virginia founder Thomas Jefferson was involved with efforts to secularize and reform the College's curriculum. Jefferson guided the College to adopt the nation's first elective system of study and to introduce the first student-adjudicated Honor System.[22]

Also at Jefferson's behest, the College appointed his friend and mentor George Wythe as the first Professor of Law in America in 1779. John Marshall, who would later go on to become Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, was one of Wythe's students. The College's Marshall-Wythe School of Law is the oldest law school in the United States.[9]

Along with establishment of new, firmer financial footing, the creation of the graduate schools in law and medicine officially made the "College" a school meeting the contemporary definition of a "university" by 1779, notwithstanding the retention of the original name as set forth in the 1693 Royal Charter.

Secret societies

The College of William and Mary has a rich tradition of secret societies and is home to the nation's first academic secret society, the Flat Hat Club. Although the pressures of the American Civil War forced many Societies to disappear, most of them were revived during the 20th Century. Some of the secret societies known to currently exist at the College are the Seven Society (Order of the Crown and Dagger), Wren Society, Bishop James Madison Society, Flat Hat Club, Alpha Club, The Society, 13 Club, the Spades, and W Society.[23][24] In addition to the popular culture notion of secret societies' wealth and extensive alumni networks, William and Mary's focus on the betterment of the College through philanthropy of a clandestine nature.

John Heath and William Short (Class of 1779) founded the Phi Beta Kappa academic honor society at William & Mary on December 5, 1776 as a secret literary and philosophical society. Additional chapters were soon established at Yale and at Harvard,[25] and there are now 270 chapters nationwide.[citation needed] Alumni John Marshall and Bushrod Washington were two of the earliest members of Phi Beta Kappa, elected in 1778 and 1780, respectively.[26]

See also

References

- ^ Mary Miley Theobald. "Henricus: A New and Improved Jamestown". Colonial Williamsburg (Winter 2004-05). History.org. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ Bill Walker (October 23, 2003). "W&M Founders Include Blair and 17 Others". University Relations. W&M News. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Earl Gregg Swem Library Special Collections". Swem.wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Historical Chronology of William and Mary". Wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Webster, Homer J. (1902) "Schools and Colleges in Colonial Times," The New England Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly, v. XXVII, p. 374, Google Books entry

- ^ williamsburg hotel virginia busch garden at williamsburgpostcards.com

- ^ Schock, Eldon D. "GEO. WASHINGTON, THE SURVEYOR". Scottish Rite Journal. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ "George Wythe biographical information". Ushistory.org. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ a b "1750 - 1799 - Historical Facts". Historical Chronology of William and Mary. Wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Virginia Vignettes » What Was the Brafferton School?". Virginiavignettes.org. August, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Visits W&M". Wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ F. James Barnes, II. "William & Mary Alumni > History". Alumni.wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "1850 - 1899 | Historical Facts". Historical Chronology of William and Mary. Wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Educator Turned Soldier Saved Virginia's Oldest College from Wartime Ruin". Vaudc.org. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Earl Gregg Swem Library Special Collections". Swem.wm.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ http://www.airfields-freeman.com/VA/Airfields_VA_Hampton.htm#central

- ^ http://web.wm.edu/news/archive/index.php?id=4449

- ^ "Ash Lawn-Highland, Home of James Monroe". Ashlawnhighland.org. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ Alumni Magazine: Wren Building

- ^ The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg[dead link]

- ^ "School of Law home page". William and Mary. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ However, a biographer notes that "Jefferson would one day sharply criticize William & Mary, and eventually he designed, built, and administered the University of Virginia in open opposition to his alma mater." Willard Sterne Randall (1994). Thomas Jefferson: A Life. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-097617-9. p. 40

- ^ Shhh! The Secret Side to the College’s Lesser Known Societies - The DoG Street Journal

- ^ Peeking Into Closed Societies - The Flat Hat

- ^ "Sigma Chi/Brief History of Fraternities/Phi Beta Kappa". Shsu.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ name="pbkabout"