Bell's theorem

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

This article needs attention from an expert in Physics. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (October 2011) |

In theoretical physics, Bell's theorem (a.k.a. Bell's inequality) is a no-go theorem, loosely stating that:

No physical theory of local hidden variables can reproduce all of the predictions of quantum mechanics.

The theorem has great importance for physics and the philosophy of science, as it implies that quantum physics must necessarily violate either the principle of locality or counterfactual definiteness.[1] It is the most famous legacy of the physicist John Stewart Bell.

Results of tests of Bell's theorem agree with the predictions of quantum mechanical theory, and demonstrate that some quantum effects appear to travel faster than light. Hence the class of tenable hidden variable theories are limited to the non-local variety. However, none of the tests of the theorem performed to date has fulfilled all of the requisite conditions implicit in the theorem. Accordingly, none of the results are totally conclusive.

Overview

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

Bell’s theorem implies that the concept of local realism, favoured by Einstein, yields predictions that disagree with those of quantum mechanical theory. Because numerous experiments agree with the predictions of quantum mechanical theory, and show correlations that are stronger than could be explained by local hidden variables, the concept of local realism is thus refuted as an explanation of the physical phenomena under test, and superluminal effects are evidenced.

The theorem applies to any quantum system of two entangled qubits. The most common examples concern systems of particles that are entangled in spin or polarization.

Following the argument in the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox paper (but using the example of spin, as in David Bohm's version of the EPR argument[2][3]), Bell considered an experiment in which there are "a pair of spin one-half particles formed somehow in the singlet spin state and moving freely in opposite directions."[2] Each is sent to two distant locations at which measurements of spin are performed, along axes that are independently chosen. Each measurement yields a result of either spin-up (+) or spin-down (−).

The probability of the same result being obtained at the two locations varies, depending on the relative angles at which the two spin measurements are made, and is subject to some uncertainty for all relative angles other than perfectly parallel alignments (0° or 180°). Bell's theorem thus applies only to the statistical results from many trials of the experiment. Symbolically, the correlation between results for a single pair can be represented as either "+1" for a match, or "−1" for a non-match. While measuring the spin of these entangled particles along parallel axes will always result in identical (i.e., perfectly correlated) results, measurement at perpendicular directions will have only a 50% chance of matching (i.e., will have a 50% probability of an uncorrelated result). These basic cases are illustrated in the table below.

| Same axis | Pair 1 | Pair 2 | Pair 3 | Pair 4 | … | Pair n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alice, 0° | + | − | − | + | … | + | |

| Bob, 0° | + | − | − | + | … | + | |

| Correlation: ( | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | … | +1 | ) / n = +1 |

| (100% identical) | |||||||

| Orthogonal axes | Pair 1 | Pair 2 | Pair 3 | Pair 4 | … | Pair n | |

| Alice, 0° | + | − | + | − | … | − | |

| Bob, 90° | − | − | + | + | … | − | |

| Correlation ( | −1 | +1 | +1 | −1 | … | −1 | ) / n = 0 |

| (50% identical) |

With the measurements oriented at intermediate angles between these basic cases, the existence of local hidden variables would imply a linear variation in the correlation. However, according to quantum mechanical theory, the correlation varies as the cosine of the angle. Experimental results match the curve predicted by quantum mechanics.[citation needed]

Bell achieved his breakthrough by first deriving the results that local realism would necessarily yield. Without making any assumptions about the specific form of the theory beyond requirements of basic consistency, the mathematical inequality he discovered was clearly at odds with the results (described above) predicted by quantum mechanics and, later, observed experimentally. Thus, Bell's theorem rules out local hidden variables as a viable explanation of quantum mechanics (though it still leaves the door open for non-local hidden variables). Bell concluded:

In a theory in which parameters are added to quantum mechanics to determine the results of individual measurements, without changing the statistical predictions, there must be a mechanism whereby the setting of one measuring device can influence the reading of another instrument, however remote. Moreover, the signal involved must propagate instantaneously, so that a theory could not be Lorentz invariant.

— [2]

Over the years, Bell's theorem has undergone a wide variety of experimental tests. Various common deficiencies in the testing of the theorem have been identified, including the detection loophole[4] and the communication loophole.[4] Over the years experiments have been gradually improved to better address these loopholes, but no experiment to date has simultaneously fully addressed all of them.[4] To date, Bell's theorem is supported by a substantial body of evidence and is treated as a fundamental principle of physics in mainstream quantum mechanics textbooks.[5][6] However, no principle of physics can ever be absolutely beyond question; some theorists argue that experimental loopholes or hidden assumptions refute the theorem's validity,[7][8][9] though most physicists accept that experiments confirm the violation of Bell inequalities.[10]

Importance of the theorem

Bell's theorem, derived in his seminal 1964 paper titled On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox,[2] has been called "the most profound in science".[11] The title of the article refers to the famous paper by Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen[12] that challenged the completeness of quantum mechanics. In his paper, Bell started from the same two assumptions as did EPR, namely (i) reality (that microscopic objects have real properties determining the outcomes of quantum mechanical measurements), and (ii) locality (that reality is not influenced by measurements performed simultaneously at a large distance). Bell was able to derive from those two assumptions an important result, namely Bell's inequality, implying that at least one of the assumptions must be false.

In two respects Bell's 1964 paper was a step forward compared to the EPR paper: firstly, it considered more hidden variables than merely the element of physical reality in the EPR paper; and, more importantly, Bell's inequality was liable to be experimentally tested, thus yielding the opportunity to convert the question of local realism from philosophy to physics. Whereas Bell's paper deals only with deterministic hidden variable theories, Bell's theorem was later generalized to stochastic theories[13] as well, and it was also realised[14] that the theorem can even be proven without introducing hidden variables.

After the EPR paper, quantum mechanics was in an unsatisfactory position: either it was incomplete, in the sense that it failed to account for some elements of physical reality, or it violated the principle of a finite propagation speed of physical effects. In a modified version of the EPR thought experiment, two hypothetical observers, now commonly referred to as Alice and Bob, perform independent measurements of spin on a pair of electrons, prepared at a source in a special state called a spin singlet state. It is the conclusion of EPR that once Alice measures spin in one direction (e.g. on the x axis), Bob's measurement in that direction is determined with certainty, as being the opposite outcome to that of Alice, whereas immediately before Alice's measurement Bob's outcome was only statistically determined (i.e., was only a probability, not a certainty); thus, either the spin in each direction is an element of physical reality, or the effects travel from Alice to Bob instantly.

In QM, predictions are formulated in terms of probabilities — for example, the probability that an electron will be detected in a particular place, or the probability that its spin is up or down. The idea persisted, however, that the electron in fact has a definite position and spin, and that QM's weakness is its inability to predict those values precisely. The possibility existed that some unknown theory, such as a hidden variables theory, might be able to predict those quantities exactly, while at the same time also being in complete agreement with the probabilities predicted by QM. If such a hidden variables theory exists, then because the hidden variables are not described by QM the latter would be an incomplete theory.

Two assumptions drove the desire to find a local realist theory:

- Objects have a definite state that determines the values of all other measurable properties, such as position and momentum.

- Effects of local actions, such as measurements, cannot travel faster than the speed of light (in consequence of special relativity). Thus if observers are sufficiently far apart, a measurement made by one can have no effect on a measurement made by the other.

In the form of local realism used by Bell, the predictions of the theory result from the application of classical probability theory to an underlying parameter space. By a simple argument based on classical probability, he showed that correlations between measurements are bounded in a way that is violated by QM.

Bell's theorem seemed to put an end to local realism. According to Bell's theorem, either quantum mechanics or local realism is wrong, as they are mutually exclusive. The paper noted that "it requires little imagination to envisage the experiments involved actually being made",[2] to determine which of them is correct, but it took many years and many improvements in technology to perform them.

The Bell test experiments have been interpreted as showing that the Bell inequalities are violated in favour of QM. The no-communication theorem shows that the observers cannot use the effect to communicate (classical) information to each other faster than the speed of light, but the ‘fair sampling’ and ‘no enhancement’ assumptions require more careful consideration (below).

John Bell's paper examines both John von Neumann's 1932 proof of the incompatibility of hidden variables with QM and the seminal 1935 EPR paper on the subject by Albert Einstein and his colleagues.

Bell inequalities

Bell inequalities concern measurements made by observers on pairs of particles that have interacted and then separated. According to quantum mechanics they are entangled, while local realism would limit the correlation of subsequent measurements of the particles.

Different authors subsequently derived inequalities similar to Bell´s original inequality, and these are here collectively termed Bell inequalities. All Bell inequalities describe experiments in which the predicted result from quantum entanglement differs from that flowing from local realism. The inequalities assume that each quantum-level object has a well-defined state that accounts for all its measurable properties and that distant objects do not exchange information faster than the speed of light. These well-defined states are typically called hidden variables, the properties that Einstein posited when he stated his famous objection to quantum mechanics: "God does not play dice."

Bell showed that under quantum mechanics, the mathematics of which contains no local hidden variables, the Bell inequalities can nevertheless be violated: the properties of a particle are not clear, but may be correlated with those of another particle due to quantum entanglement, allowing their state to be well defined only after a measurement is made on either particle. That restriction agrees with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics.

In Bell's words:

Theoretical physicists live in a classical world, looking out into a quantum-mechanical world. The latter we describe only subjectively, in terms of procedures and results in our classical domain. (…) Now nobody knows just where the boundary between the classical and the quantum domain is situated. (…) More plausible to me is that we will find that there is no boundary. The wave functions would prove to be a provisional or incomplete description of the quantum-mechanical part. It is this possibility, of a homogeneous account of the world, which is for me the chief motivation of the study of the so-called "hidden variable" possibility.

(…) A second motivation is connected with the statistical character of quantum-mechanical predictions. Once the incompleteness of the wave function description is suspected, it can be conjectured that random statistical fluctuations are determined by the extra "hidden" variables — "hidden" because at this stage we can only conjecture their existence and certainly cannot control them.

(…) A third motivation is in the peculiar character of some quantum-mechanical predictions, which seem almost to cry out for a hidden variable interpretation. This is the famous argument of Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen. (…) We will find, in fact, that no local deterministic hidden-variable theory can reproduce all the experimental predictions of quantum mechanics. This opens the possibility of bringing the question into the experimental domain, by trying to approximate as well as possible the idealized situations in which local hidden variables and quantum mechanics cannot agree.[15]

In probability theory, repeated measurements of system properties can be regarded as repeated sampling of random variables. In Bell's experiment, Alice can choose a detector setting to measure either or and Bob can choose a detector setting to measure either or . Measurements of Alice and Bob may be somehow correlated with each other, but the Bell inequalities say that if the correlation stems from local random variables, there is a limit to the amount of correlation one might expect to see.

Original Bell's inequality

The original inequality that Bell derived was:[2]

where C is the "correlation" of the particle pairs and a, b and c settings of the apparatus. This inequality is not used in practice. For one thing, it is true only for genuinely "two-outcome" systems, not for the "three-outcome" ones (with possible outcomes of zero as well as +1 and −1) encountered in real experiments. For another, it applies only to a very restricted set of hidden variable theories, namely those for which the outcomes on both sides of the experiment are always exactly anticorrelated when the analysers are parallel, in agreement with the quantum mechanical prediction.

A simple limit of Bell's inequality has the virtue of being completely intuitive. If the result of three different statistical coin-flips A, B, and C have the property that:

- A and B are the same (both heads or both tails) 99% of the time

- B and C are the same 99% of the time

then A and C are the same at least 98% of the time. The number of mismatches between A and B (1/100) plus the number of mismatches between B and C (1/100) are together the maximum possible number of mismatches between A and C.

In quantum mechanics, by letting A, B, and C be the values of the spin of two entangled particles measured relative to some axis at 0 degrees, θ degrees, and 2θ degrees respectively, the overlap of the wavefunction between the different angles is proportional to . The probability that A and B give the same answer is , where is proportional to θ. This is also the probability that B and C give the same answer. But A and C are the same 1 − (2ε)2 of the time. Choosing the angle so that , A and B are 99% correlated, B and C are 99% correlated and A and C are only 96% correlated.

Imagine that two entangled particles in a spin singlet are shot out to two distant locations, and the spins of both are measured in the direction A. The spins are 100% correlated (actually, anti-correlated but for this argument that is equivalent). The same is true if both spins are measured in directions B or C. It is safe to conclude that any hidden variables that determine the A,B, and C measurements in the two particles are 100% correlated and can be used interchangeably.

If A is measured on one particle and B on the other, the correlation between them is 99%. If B is measured on one and C on the other, the correlation is 99%. This allows us to conclude that the hidden variables determining A and B are 99% correlated and B and C are 99% correlated. But if A is measured in one particle and C in the other, the results are only 96% correlated, which is a contradiction. The intuitive formulation is due to David Mermin, while the small-angle limit is emphasized in Bell's original article.

CHSH inequality

In addition to Bell's original inequality,[2] the form given by John Clauser, Michael Horne, Abner Shimony and R. A. Holt,[16] (the CHSH form) is especially important,[16] as it gives classical limits to the expected correlation for the above experiment conducted by Alice and Bob:

where C denotes correlation.

Correlation of observables X, Y is defined as

This is a non-normalized form of the correlation coefficient considered in statistics (see Quantum correlation).

To formulate Bell's theorem, we formalize local realism as follows:

- There is a probability space and the observed outcomes by both Alice and Bob result by random sampling of the parameter .

- The values observed by Alice or Bob are functions of the local detector settings and the hidden parameter only. Thus

- Value observed by Alice with detector setting is

- Value observed by Bob with detector setting is

Implicit in assumption 1) above, the hidden parameter space has a probability measure and the expectation of a random variable X on with respect to is written

where for accessibility of notation we assume that the probability measure has a density.

Bell's inequality. The CHSH inequality (1) holds under the hidden variables assumptions above.

For simplicity, let us first assume the observed values are +1 or −1; we remove this assumption in Remark 1 below.

Let . Then at least one of

is 0. Thus

and therefore

- Remark 1

- The correlation inequality (1) still holds if the variables , are allowed to take on any real values between −1 and +1. Indeed, the relevant idea is that each summand in the above average is bounded above by 2. This is easily seen as true in the more general case:

To justify the upper bound 2 asserted in the last inequality, without loss of generality, we can assume that

In that case

- Remark 2

- Though the important component of the hidden parameter in Bell's original proof is associated with the source and is shared by Alice and Bob, there may be others that are associated with the separate detectors, these others being independent. This argument was used by Bell in 1971, and again by Clauser and Horne in 1974,[13] to justify a generalisation of the theorem forced on them by the real experiments, in which detectors were never 100% efficient. The derivations were given in terms of the averages of the outcomes over the local detector variables. The formalisation of local realism was thus effectively changed, replacing A and B by averages and retaining the symbol but with a slightly different meaning. It was henceforth restricted (in most theoretical work) to mean only those components that were associated with the source.

However, with the extension proved in Remark 1, CHSH inequality still holds even if the instruments themselves contain hidden variables. In that case, averaging over the instrument hidden variables gives new variables:

on , which still have values in the range [−1, +1] to which we can apply the previous result.

Bell inequalities are violated by quantum mechanical predictions

In the usual quantum mechanical formalism, the observables X and Y are represented as self-adjoint operators on a Hilbert space. To compute the correlation, assume that X and Y are represented by matrices in a finite dimensional space and that X and Y commute; this special case suffices for our purposes below. The von Neumann measurement postulate states: a series of measurements of an observable X on a series of identical systems in state produces a distribution of real values. By the assumption that observables are finite matrices, this distribution is discrete. The probability of observing λ is non-zero if and only if λ is an eigenvalue of the matrix X and moreover the probability is

where EX (λ) is the projector corresponding to the eigenvalue λ. The system state immediately after the measurement is

From this, we can show that the correlation of commuting observables X and Y in a pure state is

We apply this fact in the context of the EPR paradox. The measurements performed by Alice and Bob are spin measurements on electrons. Alice can choose between two detector settings labelled a and a′; these settings correspond to measurement of spin along the z or the x axis. Bob can choose between two detector settings labelled b and b′; these correspond to measurement of spin along the z′ or x′ axis, where the x′ – z′ coordinate system is rotated 135° relative to the x – z coordinate system. The spin observables are represented by the 2 × 2 self-adjoint matrices:

These are the Pauli spin matrices normalized so that the corresponding eigenvalues are +1, −1. As is customary, we denote the eigenvectors of Sx by

Let be the spin singlet state for a pair of electrons discussed in the EPR paradox. This is a specially constructed state described by the following vector in the tensor product

Now let us apply the CHSH formalism to the measurements that can be performed by Alice and Bob.

The operators , correspond to Bob's spin measurements along x′ and z′. Note that the A operators commute with the B operators, so we can apply our calculation for the correlation. In this case, we can show that the CHSH inequality fails. In fact, a straightforward calculation shows that

and

so that

Bell's Theorem: If the quantum mechanical formalism is correct, then the system consisting of a pair of entangled electrons cannot satisfy the principle of local realism. Note that is indeed the upper bound for quantum mechanics called Tsirelson's bound. The operators giving this maximal value are always isomorphic to the Pauli matrices.

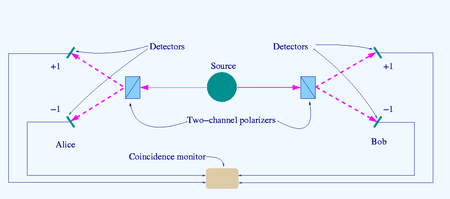

Practical experiments testing Bell's theorem

The source S produces pairs of "photons", sent in opposite directions. Each photon encounters a two-channel polariser whose orientation (a or b) can be set by the experimenter. Emerging signals from each channel are detected and coincidences of four types (++, −−, +− and −+) counted by the coincidence monitor.

Experimental tests can determine whether the Bell inequalities required by local realism hold up to the empirical evidence.

Bell's inequalities are tested by "coincidence counts" from a Bell test experiment such as the optical one shown in the diagram. Pairs of particles are emitted as a result of a quantum process, analysed with respect to some key property such as polarisation direction, then detected. The setting (orientations) of the analysers are selected by the experimenter.

Bell test experiments to date overwhelmingly violate Bell's inequality. Indeed, a table of Bell test experiments performed prior to 1986 is given in 4.5 of Redhead, 1987.[17] Of the thirteen experiments listed, only two reached results contradictory to quantum mechanics; moreover, according to the same source, when the experiments were repeated, "the discrepancies with QM could not be reproduced".

Nevertheless, the issue is not conclusively settled. According to Shimony's 2004 Stanford Encyclopedia overview article:[4]

Most of the dozens of experiments performed so far have favored Quantum Mechanics, but not decisively because of the 'detection loopholes' or the 'communication loophole.' The latter has been nearly decisively blocked by a recent experiment and there is a good prospect for blocking the former.

To explore the 'detection loophole', one must distinguish the classes of homogeneous and inhomogeneous Bell inequality.

The standard assumption in Quantum Optics is that "all photons of given frequency, direction and polarization are identical" so that photodetectors treat all incident photons on an equal basis. Such a fair sampling assumption generally goes unacknowledged, yet it effectively limits the range of local theories to those that conceive of the light field as corpuscular. The assumption excludes a large family of local realist theories, in particular, Max Planck's description. We must remember the cautionary words of Albert Einstein[18] shortly before he died: "Nowadays every Tom, Dick and Harry ('jeder Kerl' in German original) thinks he knows what a photon is, but he is mistaken".

Objective physical properties for Bell’s analysis (local realist theories) include the wave amplitude of a light signal. Those who maintain the concept of duality, or simply of light being a wave, recognize the possibility or actuality that the emitted atomic light signals have a range of amplitudes and, furthermore, that the amplitudes are modified when the signal passes through analyzing devices such as polarizers and beam splitters. It follows that not all signals have the same detection probability.[19]

Two classes of Bell inequalities

The fair sampling problem was faced openly in the 1970s. In early designs of their 1973 experiment, Freedman and Clauser[20] used fair sampling in the form of the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH[16]) hypothesis. However, shortly afterwards Clauser and Horne[13] made the important distinction between inhomogeneous (IBI) and homogeneous (HBI) Bell inequalities. Testing an IBI requires that we compare certain coincidence rates in two separated detectors with the singles rates of the two detectors. Nobody needed to perform the experiment, because singles rates with all detectors in the 1970s were at least ten times all the coincidence rates. So, taking into account this low detector efficiency, the QM prediction actually satisfied the IBI. To arrive at an experimental design in which the QM prediction violates IBI we require detectors whose efficiency exceeds 82% for singlet states, but have very low dark rate and short dead and resolving times. This is well above the 30% achievable[21] so Shimony’s optimism in the Stanford Encyclopedia, quoted in the preceding section, appears over-stated.

Practical challenges

Because detectors don't detect a large fraction of all photons, Clauser and Horne[13] recognized that testing Bell's inequality requires some extra assumptions. They introduced the No Enhancement Hypothesis (NEH):

A light signal, originating in an atomic cascade for example, has a certain probability of activating a detector. Then, if a polarizer is interposed between the cascade and the detector, the detection probability cannot increase.

Given this assumption, there is a Bell inequality between the coincidence rates with polarizers and coincidence rates without polarizers.

The experiment was performed by Freedman and Clauser,[20] who found that the Bell's inequality was violated. So the no-enhancement hypothesis cannot be true in a local hidden variables model. The Freedman-Clauser experiment reveals that local hidden variables imply the new phenomenon of signal enhancement:

In the total set of signals from an atomic cascade there is a subset whose detection probability increases as a result of passing through a linear polarizer.

This is perhaps not surprising, as it is known that adding noise to data can, in the presence of a threshold, help reveal hidden signals (this property is known[22] as stochastic resonance). One cannot conclude that this is the only local-realist alternative to Quantum Optics, but it does show that the word loophole is biased. Moreover, the analysis leads us to recognize that the Bell-inequality experiments, rather than showing a breakdown of realism or locality, are capable of revealing important new phenomena.

Theoretical challenges

Most advocates of the hidden variables idea believe that experiments have ruled out local hidden variables. They are ready to give up locality, explaining the violation of Bell's inequality by means of a "non-local" hidden variable theory, in which the particles exchange information about their states. This is the basis of the Bohm interpretation of quantum mechanics, which requires that all particles in the universe be able to instantaneously exchange information with all others. A recent experiment ruled out a large class of non-Bohmian "non-local" hidden variable theories.[23]

If the hidden variables can communicate with each other faster than light, Bell's inequality can easily be violated. Once one particle is measured, it can communicate the necessary correlations to the other particle. Since in relativity the notion of simultaneity is not absolute, this is unattractive. One idea is to replace instantaneous communication with a process that travels backwards in time along the past Light cone. This is the idea behind a transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics, which interprets the statistical emergence of a quantum history as a gradual coming to agreement between histories that go both forward and backward in time.[24]

A few advocates of deterministic models have not given up on local hidden variables. For example, Gerard 't Hooft has argued that the superdeterminism loophole cannot be dismissed.[25][26]

The quantum mechanical wavefunction can also provide a local realistic description, if the wavefunction values are interpreted as the fundamental quantities that describe reality. Such an approach is called a many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In this view, two distant observers both split into superpositions when measuring a spin. The Bell inequality violations are no longer counterintuitive, because it is not clear which copy of the observer B observer A will see when going to compare notes. If reality includes all the different outcomes, locality in physical space (not outcome space) places no restrictions on how the split observers can meet up.

This implies that there is a subtle assumption in the argument that realism is incompatible with quantum mechanics and locality. The assumption, in its weakest form, is called counterfactual definiteness. This states that if the results of an experiment are always observed to be definite, there is a quantity that determines what the outcome would have been even if you don't do the experiment.

Many worlds interpretations are not only counterfactually indefinite, they are factually indefinite. The results of all experiments, even ones that have been performed, are not uniquely determined.

Jaynes [27]pointed out two hidden assumptions in Bell Inequality that could limit its generality:

- Bell interpreted conditional probability P(X|Y) as a causal inference, i.e. Y exerted a causal inference on X in reality. However, P(X|Y) actually only means logical inference (deduction). Causes cannot travel faster than light or backward in time, but deduction can.

- Bell's inequality does not apply to some possible hidden variable theories. It only applies to a certain class of local hidden variable theories. In fact, it might have just missed the kind of hidden variable theories that Einstein is most interested in.

Final remarks

The violations of Bell's inequalities, due to quantum entanglement, just provide the definite demonstration of something that was already strongly suspected, that quantum physics cannot be represented by any version of the classical picture of physics. Some earlier elements that had seemed incompatible with classical pictures included apparent complementarity and (hypothesized) wavefunction collapse. Complementarity is now seen not as an independent ingredient of the quantum picture but rather as a direct consequence of the Quantum decoherence expected from the quantum formalism itself. The possibility of wavefunction collapse is now seen as one possible problematic ingredient of some interpretations, rather than as an essential part of quantum mechanics. The Bell violations show that no resolution of such issues can avoid the ultimate strangeness of quantum behavior.

The EPR paper "pinpointed" the unusual properties of the entangled states, e.g. the above-mentioned singlet state, which is the foundation for present-day applications of quantum physics, such as quantum cryptography; one application involves the measurement of quantum entanglement as a physical source of bits for Rabin's oblivious transfer protocol. This strange non-locality was originally supposed to be a Reductio ad absurdum, because the standard interpretation could easily do away with action-at-a-distance by simply assigning to each particle definite spin-states. Bell's theorem showed that the "entangledness" prediction of quantum mechanics have a degree of non-locality that cannot be explained away by any local theory.

In well-defined Bell experiments (see the paragraph on "test experiments") one can now falsify either quantum mechanics or Einstein's quasi-classical assumptions: currently many experiments of this kind have been performed, and the experimental results support quantum mechanics, though some believe that detectors give a biased sample of photons, so that until nearly every photon pair generated is observed there will be loopholes.

What is powerful about Bell's theorem is that it doesn't refer to any particular physical theory. What makes Bell's theorem unique and powerful is that it shows that nature violates the most general assumptions behind classical pictures, not just details of some particular models. No combination of local deterministic and local random variables can reproduce the phenomena predicted by quantum mechanics and repeatedly observed in experiments.

See also

- Bell test experiments

- CHSH Bell test

- Counterfactual definiteness

- Fundamental Fysiks Group

- GHZ experiment

- Local hidden variable theory

- Leggett inequality

- Leggett–Garg inequality

- Measurement in quantum mechanics

- Mott problem

- Quantum entanglement

- Quantum mechanical Bell test prediction

- Renninger negative-result experiment

Notes

- ^ Blaylock, Guy (2010). "The EPR paradox, Bell's inequality, and the question of locality". American Journal of Physics. 78 (1): 111–120. arXiv:0902.3827. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78..111B. doi:10.1119/1.3243279.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bell, John (1964). "On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox" (PDF). Physics. 1 (3): 195–200.

- ^ Bohm, David Quantum Theory. Prentice-Hall, 1951.

- ^ a b c d Article on Bell's Theorem by Abner Shimony in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (2004).

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1998). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 423.

- ^ Merzbacher, Eugene (2005). Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 18, 362.

- ^ Buchanan, Mark (2 November 2007). "Quantum Untanglement: Is spookiness under threat?". New Scientist.

- ^ Joy Christian (2011). "Disproof of Bell's Theorem". arXiv:1103.1879 [quant-ph].

- ^ Thompson (1996). "The Chaotic Ball: An Intuitive Analogy for EPR Experiments". Foundations of Physics Letters. 9 (4): 357–382. arXiv:quant-ph/9611037. Bibcode:1996FoPhL...9..357T. doi:10.1007/BF02186307.

- ^ Kumar, M. (2009). Quantum. Icon Books. p. 350.

- ^ Stapp, 1975

- ^ Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. (1935). "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?". Physical Review. 47 (10): 777. Bibcode:1935PhRv...47..777E. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.47.777.

- ^ a b c d Clauser, John F. (1974). "Experimental consequences of objective local theories". Physical Review D. 10 (2): 526. Bibcode:1974PhRvD..10..526C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.526.

- ^ Eberhard, P. H. (1977). "Bell's theorem without hidden variables". Nuovo Cimento B. 38: 75–80. Bibcode:1977NCimB..38...75E. doi:10.1007/BF02726212.

- ^ Bell, JS, Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics: Introduction remarks at Naples-Amalfi meeting., 1984. Reprinted in Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics: collected papers on quantum philosophy. CUP, 2004, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Clauser, John; Horne, Michael; Shimony, Abner; Holt, Richard (1969). "Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories". Physical Review Letters. 23 (15): 880. Bibcode:1969PhRvL..23..880C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.880.

- ^ M. Redhead, Incompleteness, Nonlocality and Realism, Clarendon Press (1987)

- ^ A. Einstein in Correspondance Einstein–Besso, p.265 (Herman, Paris, 1979)

- ^ Marshall and Santos, Semiclassical optics as an alternative to nonlocality Recent Research Developments in Optics 2:683-717 (2002) ISBN 81-7736-140-6

- ^ a b Freedman, Stuart J.; Clauser, John F. (1972). "Experimental Test of Local Hidden-Variable Theories". Physical Review Letters. 28 (14): 938. Bibcode:1972PhRvL..28..938F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.28.938.

- ^ Giorgio Brida; Marco Genovese; Marco Gramegna; Fabrizio Piacentini; Enrico Predazzi; Ivano Ruo-Berchera (2007). "Experimental tests of hidden variable theories from dBB to Stochastic Electrodynamics". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 67 (12047): 012047. arXiv:quant-ph/0612075. Bibcode:2007JPhCS..67a2047G. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/67/1/012047.

- ^ Gammaitoni, Luca; Hänggi, Peter; Jung, Peter; Marchesoni, Fabio (1998). "Stochastic resonance". Reviews of Modern Physics. 70: 223. Bibcode:1998RvMP...70..223G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.223.

- ^ Gröblacher, Simon; Paterek, Tomasz; Kaltenbaek, Rainer; Brukner, Časlav; Żukowski, Marek; Aspelmeyer, Markus; Zeilinger, Anton (2007). "An experimental test of non-local realism". Nature. 446 (7138): 871–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..871G. doi:10.1038/nature05677. PMID 17443179.

- ^ Cramer, John (1986). "The transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics". Reviews of Modern Physics. 58 (3): 647. Bibcode:1986RvMP...58..647C. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.58.647.

- ^ Gerard 't Hooft (2009). "Entangled quantum states in a local deterministic theory". arXiv:0908.3408 [quant-ph].

- ^ Gerard 't Hooft (2007). "The Free-Will Postulate in Quantum Mechanics". arXiv:quant-ph/0701097.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help) - ^ Jaynes, E. T. (1989). "Clearing up Mysteries--The Original Goal". Maximum Entropy and Bayesian Methods: 12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|link=ignored (help)

References

- A. Aspect et al., Experimental Tests of Realistic Local Theories via Bell's Theorem, Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 460 (1981)

- A. Aspect et al., Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell's Inequalities, Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 91 (1982).

- A. Aspect et al., Experimental Test of Bell's Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers, Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1804 (1982).

- A. Aspect and P. Grangier, About resonant scattering and other hypothetical effects in the Orsay atomic-cascade experiment tests of Bell inequalities: a discussion and some new experimental data, Lettere al Nuovo Cimento 43, 345 (1985)

- B. D'Espagnat, The Quantum Theory and Reality, Scientific American, 241, 158 (1979)

- J. S. Bell, On the problem of hidden variables in quantum mechanics, Rev. Mod. Phys. 38, 447 (1966)

- J. S. Bell, On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox, Physics 1, 3, 195-200 (1964)

- J. S. Bell, Introduction to the hidden variable question, Proceedings of the International School of Physics 'Enrico Fermi', Course IL, Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (1971) 171–81

- J. S. Bell, Bertlmann’s socks and the nature of reality, Journal de Physique, Colloque C2, suppl. au numero 3, Tome 42 (1981) pp C2 41–61

- J. S. Bell, Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics (Cambridge University Press 1987) [A collection of Bell's papers, including all of the above.]

- J. F. Clauser and A. Shimony, Bell's theorem: experimental tests and implications, Reports on Progress in Physics 41, 1881 (1978)

- J. F. Clauser and M. A. Horne, Phys. Rev D 10, 526–535 (1974)

- E. S. Fry, T. Walther and S. Li, Proposal for a loophole-free test of the Bell inequalities, Phys. Rev. A 52, 4381 (1995)

- E. S. Fry, and T. Walther, Atom based tests of the Bell Inequalities — the legacy of John Bell continues, pp 103–117 of Quantum [Un]speakables, R.A. Bertlmann and A. Zeilinger (eds.) (Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, 2002)

- R. B. Griffiths, Consistent Quantum Theory', Cambridge University Press (2002).

- L. Hardy, Nonlocality for 2 particles without inequalities for almost all entangled states. Physical Review Letters 71 (11) 1665–1668 (1993)

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press (2000)

- P. Pearle, Hidden-Variable Example Based upon Data Rejection, Physical Review D 2, 1418–25 (1970)

- A. Peres, Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods, Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1993.

- P. Pluch, Theory of Quantum Probability, PhD Thesis, University of Klagenfurt, 2006.

- B. C. van Frassen, Quantum Mechanics, Clarendon Press, 1991.

- M.A. Rowe, D. Kielpinski, V. Meyer, C.A. Sackett, W.M. Itano, C. Monroe, and D.J. Wineland, Experimental violation of Bell's inequalities with efficient detection,(Nature, 409, 791–794, 2001).

- S. Sulcs, The Nature of Light and Twentieth Century Experimental Physics, Foundations of Science 8, 365–391 (2003)

- S. Gröblacher et al., An experimental test of non-local realism,(Nature, 446, 871–875, 2007).

- D. N. Matsukevich, P. Maunz, D. L. Moehring, S. Olmschenk, and C. Monroe, Bell Inequality Violation with Two Remote Atomic Qubits, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 150404 (2008).

- The comic Dilbert, by Scott Adams, refers to Bell's Theorem in the 1992-09-21 and 1992-09-22 strips.

Further reading

The following are intended for general audiences.

- Amir D. Aczel, Entanglement: The greatest mystery in physics (Four Walls Eight Windows, New York, 2001).

- A. Afriat and F. Selleri, The Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen Paradox (Plenum Press, New York and London, 1999)

- J. Baggott, The Meaning of Quantum Theory (Oxford University Press, 1992)

- N. David Mermin, "Is the moon there when nobody looks? Reality and the quantum theory", in Physics Today, April 1985, pp. 38–47.

- Louisa Gilder, The Age of Entanglement: When Quantum Physics Was Reborn (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008)

- Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos (Vintage, 2004, ISBN 0-375-72720-5)

- Nick Herbert, Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics (Anchor, 1987, ISBN 0-385-23569-0)

- D. Wick, The infamous boundary: seven decades of controversy in quantum physics (Birkhauser, Boston 1995)

- R. Anton Wilson, Prometheus Rising (New Falcon Publications, 1997, ISBN 1-56184-056-4)

- Gary Zukav "The Dancing Wu Li Masters" (Perennial Classics, 2001, ISBN 0-06-095968-1)

External links

- An explanation of Bell's Theorem, based on N. D. Mermin's article, Mermin, N. D. (1981). "Bringing home the atomic world: Quantum mysteries for anybody". American Journal of Physics. 49 (10): 940. Bibcode:1981AmJPh..49..940M. doi:10.1119/1.12594.

- Quantum Entanglement Includes a simple explanation of Bell's Inequality.

- Bell's theorem on arXiv.org

- Interactive experiments with single photons: entanglement and Bell´s theorem

![{\displaystyle \ (1)\quad \mathbf {C} [A(a),B(b)]+\mathbf {C} [A(a),B(b')]+\mathbf {C} [A(a'),B(b)]-\mathbf {C} [A(a'),B(b')]\leq 2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/19883bdd0f40a32978deae542f4c5852af14169a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\quad A(a,\lambda )B(b,\lambda )+A(a,\lambda )B(b',\lambda )+A(a',\lambda )B(b,\lambda )-A(a',\lambda )\ B(b',\lambda )\\&=A(a,\lambda )\left(B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda )\right)+A(a',\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda )\right]\\&\leq 2\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/346735afac0423e369e5df21e1157865add4cc28)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\quad \mathbf {C} (A(a),B(b))+\mathbf {C} (A(a),B(b'))+\mathbf {C} (A(a'),B(b))-\mathbf {C} (A(a'),B(b'))&\\&=\int _{\Lambda }A(a,\lambda )B(b,\lambda )\rho (\lambda )d\lambda +\int _{\Lambda }A(a,\lambda )B(b',\lambda )\rho (\lambda )d\lambda +\int _{\Lambda }A(a',\lambda )B(b,\lambda )\rho (\lambda )d\lambda -\int _{\Lambda }A(a',\lambda )B(b',\lambda )\rho (\lambda )d\lambda &\\&=\int _{\Lambda }{\big \{}A(a,\lambda )B(b,\lambda )+A(a,\lambda )B(b',\lambda )+A(a',\lambda )B(b,\lambda )-A(a',\lambda )B(b',\lambda ){\big \}}\rho (\lambda )d\lambda &\\&=\int _{\Lambda }{\big \{}A(a,\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda )\right]+A(a',\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda )\right]{\big \}}\rho (\lambda )d\lambda \\&\leq 2\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/664416728c6a8570d980f9dc7615b3af5cb03b50)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\quad A(a,\lambda )B(b,\lambda )+A(a,\lambda )B(b',\lambda )+A(a',\lambda )B(b,\lambda )-A(a',\lambda )B(b',\lambda )\\&=A(a,\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda )\right]+A(a',\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda )\right]\\&\leq {\big |}A(a,\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda )\right]+A(a',\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda )\right]{\big |}\\&\leq {\big |}A(a,\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda )\right]{\big |}+{\big |}A(a',\lambda )\left[B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda )\right]{\big |}\\&\leq {\big |}B(b,\lambda )+B(b',\lambda ){\big |}+{\big |}B(b,\lambda )-B(b',\lambda ){\big |}\leq 2\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0de816cc89b079605e222564264549601022b072)