Potlatch

A potlatch[1][2] is a gift-giving festival and primary economic system[3] practiced by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. This includes Heiltsuk_Nation, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian,[4] Nuu-chah-nulth,[5] Kwakwaka'wakw,[3] and Coast Salish[6] cultures. The word comes from the Chinook Jargon, meaning "to give away" or "a gift." It went through a history of rigorous ban by both the Canadian and United States' federal governments, and has been the study of many anthropologists.

Overview

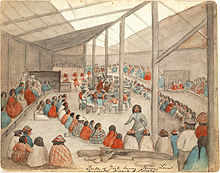

At potlatch gatherings, a family or hereditary leader hosts guests in their family's house and holds a feast for their guests. The main purpose of the potlatch is the re-distribution and reciprocity of wealth.

Different events take place during a potlatch, like singing and dancing, sometimes with masks or regalia, such as Chilkat blankets, the barter of wealth through gifts, such as dried foods, sugar, flour, or other material things, and sometimes money. For many potlatches, spiritual ceremonies take place for different occasions. This is either through material wealth such as foods and goods or non-material things such as songs and dances. For some cultures, such as Kwakwaka'wakw, elaborate and theatrical dances are performed reflecting the hosts' genealogy and cultural wealth. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa. Typically the potlatching is practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends.

Within it, hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, are observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The status of any given family is raised not by who has the most resources, but by who distributes the most resources. The hosts demonstrate their wealth and prominence through giving away goods. Chief O'wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu'ł describes the potlatch in his famous speech to anthropologist Franz Boas,

"We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, 'Do as the Indian does?' It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us."

Celebration of births, rites of passages, weddings, funerals, namings, and honoring of the deceased are some of the many forms the potlatch occurs under. Although protocol differs among the Indigenous nations, the potlatch will usually involve a feast, with music, dance, theatricality and spiritual ceremonies. The most sacred ceremonies are usually observed in the winter.

It is important to note the differences and uniqueness among the different cultural groups and nations along the coast. Each nation, tribe, and sometimes clan has its own way of practicing the potlatch with diverse presentation and meaning. The potlatch, as an overarching term, is quite general, since some cultures have many words in their language for various specific types of gatherings. Nonetheless, the main purpose has been and still is the redistribution of wealth procured by families.

History

Before the arrival of the Europeans, gifts included storable food (oolichan [candle fish] oil or dried food), canoes, and slaves among the very wealthy, but otherwise not income-generating assets such as resource rights. The influx of manufactured trade goods such as blankets and sheet copper into the Pacific Northwest caused inflation in the potlatch in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. Some groups, such as the Kwakwaka'wakw, used the potlatch as an arena in which highly competitive contests of status took place. In some cases, goods were actually destroyed after being received, or instead of being given away. The catastrophic mortalities due to introduced diseases laid many inherited ranks vacant or open to remote or dubious claim—providing they could be validated—with a suitable potlatch.[7]

The potlatch was a cultural practice much studied by ethnographers. Sponsors of a potlatch give away many useful items such as food, blankets, worked ornamental mediums of exchange called "coppers," and many other various items. In return, they earned prestige. To give a potlatch enhanced one's reputation and validated social rank, the rank and requisite potlatch being proportional, both for the host and for the recipients by the gifts exchanged. Prestige increased with the lavishness of the potlatch, the value of the goods given away in it.

Potlatch ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act[8] and the United States in the late 19th century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it "a worse than useless custom" that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to civilized values.[9]

The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was "by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized."[10] Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly, an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.[11]

Eventually the potlatch law, as it became known, was amended to be more inclusive and address technicalities that had led to dismissals of prosecutions by the court. Legislation included guests who participated in the ceremony. The indigenous people were too large to police and the law too difficult to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offense from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence."[12] Even so, except in a few small areas, the law was generally perceived as harsh and untenable. Even the Indian agents employed to enforce the legislation considered it unnecessary to prosecute, convinced instead that the potlatch would diminish as younger, educated, and more "advanced" Indians took over from the older Indians, who clung tenaciously to the custom.[13]

Continuation

Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, indigenous people now openly hold potlatch to commit to the restoring of their ancestors' ways. Potlatch now occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. The ban was only repealed in 1951.[14]

See also

- Athabaskan Potlatch

- Communism

- Koha, a similar concept among the Māori

- Kula ring, a similar concept in the Trobriand Islands (Oceania)

- Moka, another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Sepik Coast exchange, yet another similar concept in Papua New Guinea

- Guy Debord, French Situationist writer on the subject of potlatch and commodity reification.

- Gift economy

- Potluck (Folk etymology has derived the term "potluck" from the Native American custom of potlatch)

- Pow wow a gathering whose name is derived from the Narragansett word for "spiritual leader."

References

- ^ Potlatch. Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved on April 26, 2007.

- ^ Potlatch. Dictionary.com. Retrieved on April 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Aldona Jonaitis. Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. U. Washington Press 1991. ISBN 978-0295971148.

- ^ Seguin, Margaret (1986) "Understanding Tsimshian 'Potlatch.'" In: Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, ed. by R. Bruce Morrison and C. Roderick Wilson, pp. 473–500. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- ^ Atleo, Richard. Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth Worldview, UBC Press; New Ed edition (February 28, 2005). ISBN 978-0774810852

- ^ Mathews, Major J.S. Conversations with Khahtsahlano 1932–1954, Out of Print, 1955. ASIN: B0007K39O2. p190, 266, 267.

- ^ (1) Boyd (2) Cole & Chaikin

- ^ An Act further to amend "The Indian Act, 1880," S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3.

- ^ G.M. Sproat, quoted in Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), 15

- ^ Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1977, 207.

- ^ An Act further to amend "The Indian Act, 1880," S.C. 1884 (47 Vict.), c. 27, s. 3. Reproduced in n.41, Bell, Catherine (2008). "Recovering from Colonization: Perspectives of Community Members on Protection and Repatriation of Kwakwaka'wakw Cultural Heritage". In Bell, Catherine, and Val Napoleon (ed.). First Nations Cultural Heritage and Law: Case Studies, Voices, and Perspectives. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 89. ISBN 0774814624. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1991, 159.

- ^ Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Vancouver and Toronto 1990), Conclusion

- ^ Gadacz, René R. "Potlatch". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Bibliography

External links

- U'mista Museum of potlatch artifacts.

- Potlatch An exhibition from the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Oliver S. Van Olinda Photographs A collection of 420 photographs depicting life on Vashon Island, Whidbey Island, Seattle and other communities around Puget Sound, Washington, from the 1880s through the 1930s. This collection provides a glimpse of early pioneer activities, industries and occupations, recreation, street scenes, ferries and boat traffic at the turn of the century. Also included are a few photographs of Native American activities such as documentation of a potlatch on Whidbey Island.