Aging of Japan

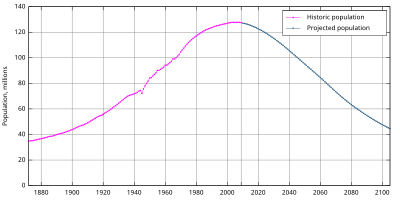

The aging of Japan outweighs all other nations with the highest proportion of elderly citizens, 21% over the age of 65.[1] In 1989, only 11.6% of the population was 65 years or older, but projections were that 25.6% would be in that age category by 2030. However, those estimates are updated at 23.1% (as of February 2011) are already 65 and over, and 11.4% are 75 and over[2], now the world's highest (though 2010 Census age results have not yet been released). The change will have taken place in a shorter span of time than in any other country.

The age 65 and above demographic group increased from 26.5 million in 2006 to 29.47 million in 2011, a 11.2% increase. The Japanese Health Ministry estimates the nation's total population will decrease by 25% from 127.8 million in 2005 to 95.2 million by 2050.[3] Japan's elderly population, aged 65 or older, comprised 20% of the nation's population in June 2006,[4] a percentage expected to increase to 40% by 2055.[5]

Causes

This aging of the population was brought about by a combination of low fertility and high life expectancies (i.e., low mortality). In 1993 the birth rate was estimated at 10.3 per 1,000 population, and the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime has been fewer than two since the late 1970s (the average number was estimated at 1.5 in 1993). Family planning was nearly universal, with condoms and legal abortions the main forms of birth control.

A number of factors contributed to the trend toward small families: high education, devotion to raising healthy children, late marriage, increased participation of women in the labor force, small living spaces, education about the problems of overpopulation, and the high costs of child education. Life expectancies at birth, 76.4 years for males and 82.2 years for women in 1993, were the highest in the world. (The expected life span at the end of World War II, for both males and females, was 50 years.) The mortality rate in 1993 was estimated at 7.2 per 1,000 population. The leading causes of death are cancer, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease, a pattern common to industrialized societies.

Effects on society

Public policy, the media, and discussions with private citizens revealed a high level of concern for the implications of one in four persons in Japan being 65 or older. By 2025 the dependency ratio (the ratio of people under age 15 plus those 65 and older to those age 15–65, indicating in a general way the ratio of the dependent population to the working population) was expected to be two dependents for every three workers. Despite claims, this is not a particularly high dependency ratio, for example, Uganda has 1.3 dependents for every one worker. The aging of the population was already becoming evident in the aging of the labor force and the shortage of young workers in the late-1980s, with potential impacts on employment practices, wages and benefits, and the roles of women in the labor force.

The increasing proportion of elderly people also had a major impact on government spending. Millions of dollars are saved every year on education and on health care and welfare for children. As recently as the early-1970s, social expenditures amounted to only about 6% of Japan's national income. In 1992 that portion of the national budget was 18%, and it was expected that by 2025, 27% of national income would be spent on social welfare.

In addition, the median age of the elderly population was rising in the late 1980s. The proportion of people age 65–85 was expected to increase from 6% in 1985 to 15% in 2025. Because the incidence of chronic disease increases with age, the health care and pension systems are expected to come under severe strain. In the mid-1980s the government began to reevaluate the relative burdens of government and the private sector in health care and pensions, and it established policies to control government costs in these programs.

A study by the UN Population Division released in 2000 found that Japan would need to raise its retirement age to 77 or admit 1 million immigrants annually between 2000 and 2050 to maintain its worker-to-retiree ratio.[6]

Recognizing the lower probability that an elderly person will be residing with an adult child and the higher probability of any daughter or daughter-in-law's participation in the paid labor force, the government encouraged establishment of nursing homes, day-care facilities for the elderly, and home health programs. Longer life spans are altering relations between spouses and across generations, creating new government responsibilities, and changing virtually all aspects of social life.

Retiring people are making way for employers to hire working age people. This has an effect of lowering the unemployment rate or selection ratio as elderly generally stop working or seek work. Japan's jobs to applicant ratio has been steadily increasing from May 2010 to early 2011[7]

Government policies

Japan has continued to experience a decreasing birth rate as it enters the 21st century. Going forward, government statistics report in 2030 there will be approximately the same amount of the working aged population as there was in 1950. [8] Japan will experience declines in the children and working aged cohorts and a sharp increase in the over 65 year old group.

The decline in the working aged cohort may lead to a shrinking economy if productivity does not increase faster than the rate of its decreasing workforce. In the next few years, the first groups of the baby boomers will reach retirement age and researchers believe this will lead to an increase in Japan’s debt, deficits, and deflation. [9]Japan would need to increase both the number of its workforce and industrial productivity to help support its aging population.

Japan is addressing these demographic problems by developing policies to help keep more of its population engaged in the workforce. The government has identified gaps between the demographic projections and the aspirations of its citizens. For instance, research has found that married couples want to have more than two children, but the current birth rate is only 1.75%. [10] Japan has focused its policies on the work-life balance with the goal of improving the conditions for increasing the birth rate. To address these challenges, Japan has established goals to define the ideal work-life balance that would provide the environment for couples to have more children with the passing of the Child Care and Family Care Leave Law, which took effect in June 2010. The law provides fathers with an opportunity to take up to eight weeks of leave after the birth of a child and allows employees with pre-school age children the following allowances: up to five days of leave in the event of a child’s injury or sickness, limits on the amount of overtime in excess of 24 hours per month based on an employee’s request, limits on working late at night based on an employee’s request, and opportunity for shorter working hours and flex time for employees. [11]

The goals of the law would strive to achieve the following results in 10 years are categorized by the female employment rate (increase from 65% to 72%), percentage of employees working 60 hours or more per week (decrease from 11% to 6%), rate of use of annual paid leave (increase from 47% to 100%), rate of child care leave (increase from 72% to 80% for females and .6% to 10% for men), and hours spent by men on child care and housework in households with a child under six years of age (increase from 1 hour to 2.5 hours a day). [12]

Comparisons with other countries

Europe

Paul S. Hewitt, an analyst for International Politics and Society, wrote in 2002 that Japan, in addition to the European nations of Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Sweden, would experience an unprecedented labor shortage by 2010. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates Japan will experience an 18% decrease in its workforce and 8% decrease in its consumer population by 2030.

Hewitt believes this decline in overall population and shortage in labor is reducing economic growth and lowering nations' gross domestic product. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates labor shortages will decrease the European Union's economic growth by 0.4% annually from 2000 to 2025 at least, after which shortages will cost the EU 0.9% in growth. In Japan these shortages will lower growth by 0.7% annually until 2025, after which Japan will also experience a 0.9% loss in growth.

North America and Australia

In contrast, Australia, Canada, and the United States will all see a growth in their workforce.[13]

See also

References

- ^ "Asia: Japan: Most Elderly Nation". The New York Times. 2006-07-01. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/pdf/201102.pdf

- ^ Japan's Elderly Population Rises to Record, Government Says Bloomberg.

- ^ "Europe's Aging Population Faces Social Problems Similar to Japan's". Goldsea Asian American Daily. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ Japan eyes robots to support aging population The Boston Globe

- ^ Unknown (2000). "Aging Populations in Europe, Japan, Korea, Require Action". India Times. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/quote?ticker=JBTARATE:IND

- ^ Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, “Trends in Population,”

- ^ “Into the Unknown.” The Economist, http://proquest.umi.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/pqdweb?did=2195236471&sid=1&Fmt=3&clientId=8724&RQT=309&VName=PQD, accessed May 22, 2011.

- ^ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Introduction to the Revised Child Care and Family Care Leave Law,” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html, accessed May 22, 2011.

- ^ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Introduction to the Revised Child Care and Family Care Leave Law,” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html, accessed May 22, 2011.

- ^ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Introduction to the Revised Child Care and Family Care Leave Law,” http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html, accessed May 22, 2011.

- ^ Paul S. Hewitt (2002). "Depopulation and Ageing in Europe and Japan: The Hazardous Transition to a Labor Shortage Economy". International Politics and Society. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

External Links

- Another Tsunami Warning: Caring for Japan’s Elderly, (NBR Expert Brief, April 2011)